- Home

- Our Stories

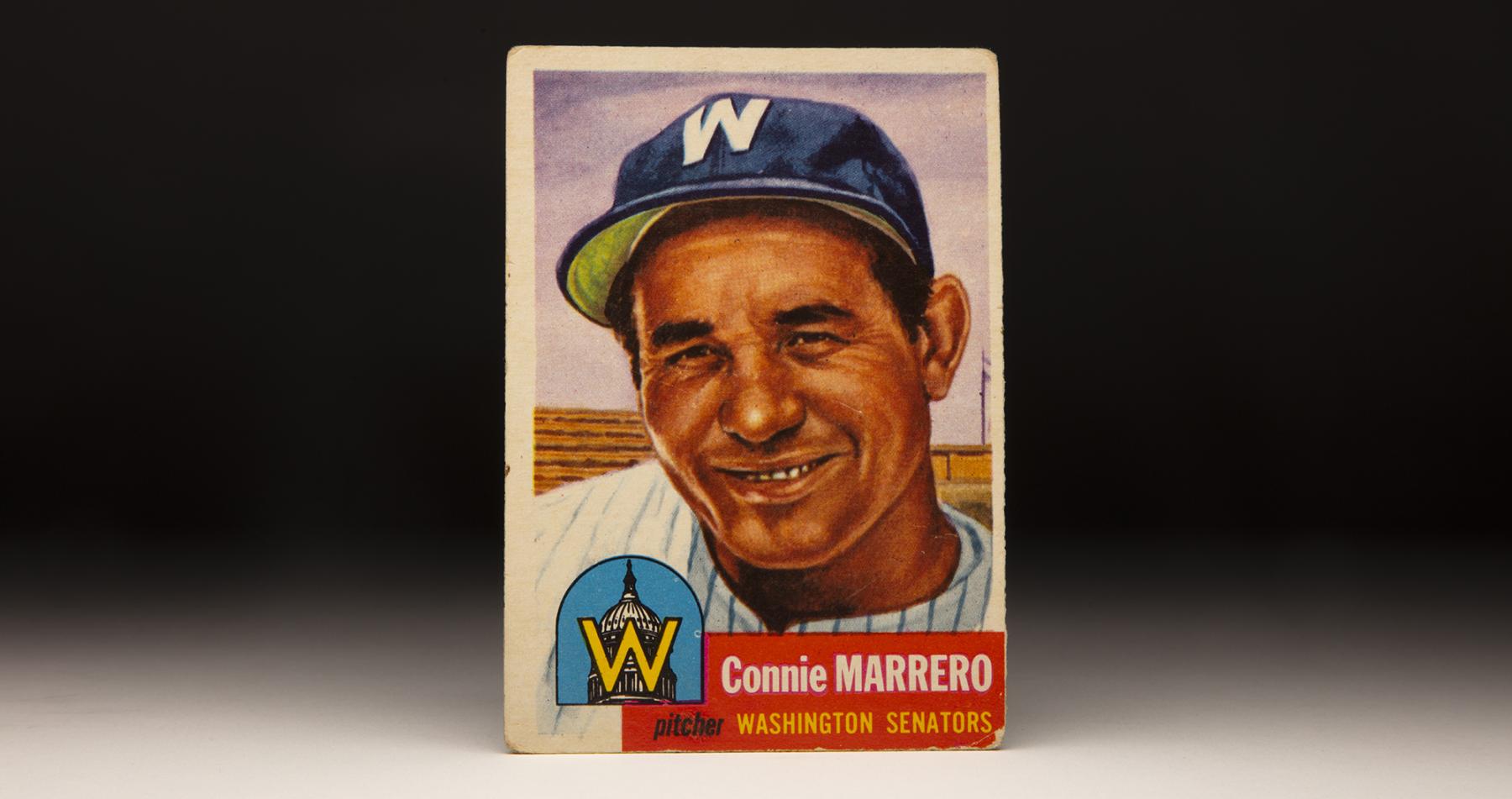

- #CardCorner: 1953 Topps Connie Marrero

#CardCorner: 1953 Topps Connie Marrero

He was an All-Star at 40, received votes for the 1952 American League Most Valuable Player the following year and became the 17th known former big leaguer to reach 100 years of age.

Conrado Eugenio Marrero was part of the first wave of Cuban players who starred in the 1950s. And he left a legacy as one of that country’s most beloved athletes.

Born April 25, 1911, in Sagua La Grande, Cuba, Marrero worked on his father’s sugar cane farm and played ball for local amateur teams throughout his youth. By his mid-20s, Marrero was pitching at the highest amateur level his country offered: the International Baseball Federation World Championships.

In 1942, Marrero led Cuba to the title.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

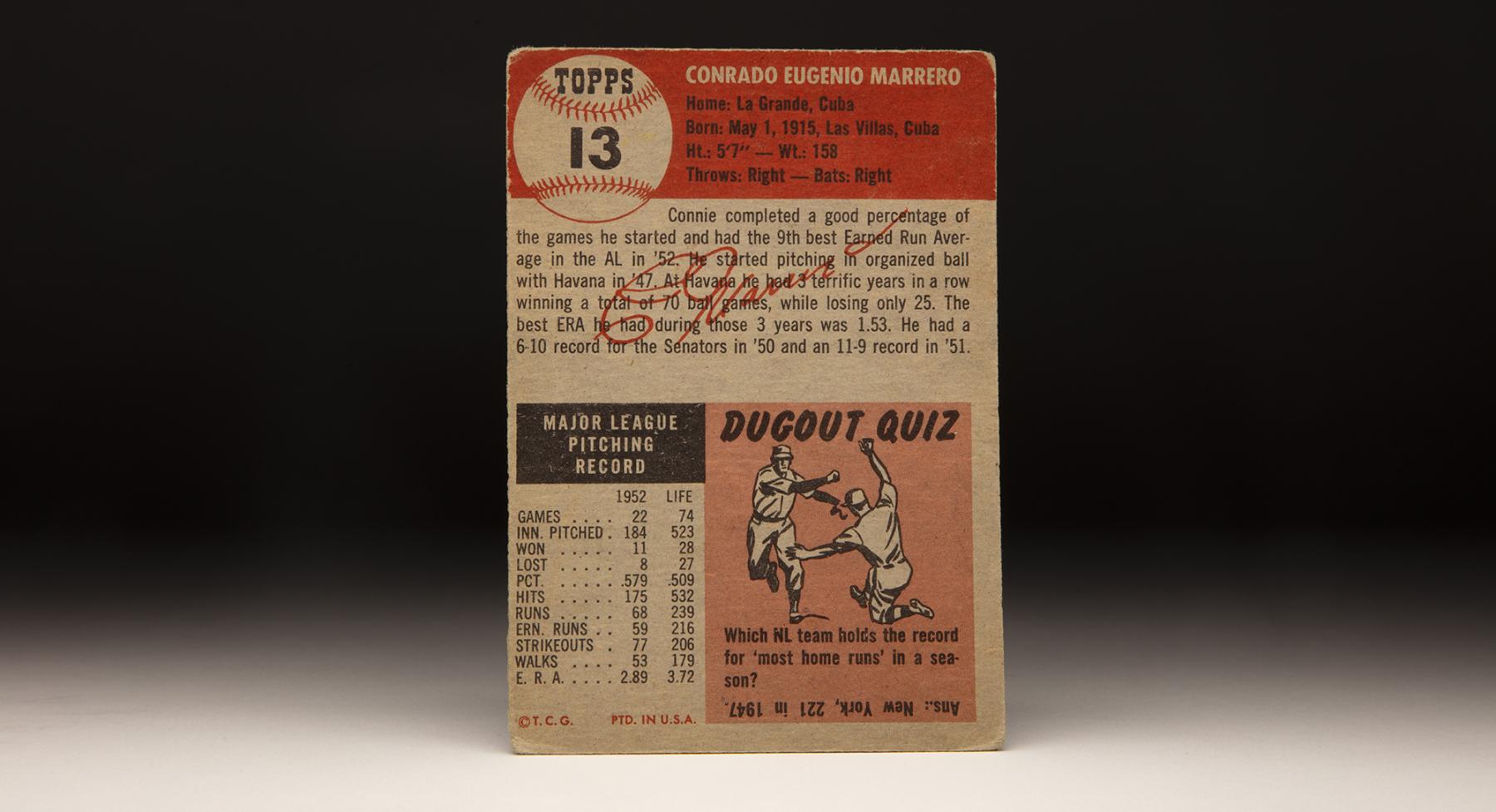

Long relying on change of speed and location for his success, Marrero pitched for the Mexican National League in 1946 (which was not related to the Mexican League that was targeting big league players at that time) and then debuted with the Havana Cubans of the Florida International League – a Class C affiliate of the Washington Senators – in 1947. The 36-year-old Marrero went 25-6 with a 1.66 ERA, overwhelming the much younger players who comprised most of the league and throwing a no-hitter against Tampa on July 12 en route to helping the team win the FIL championship.

Marrero was 20-11 with a 1.67 ERA in 1948 and followed that by going 25-8 with a 1.53 ERA in 1949. Known as “El Curvo” and listed at 5-foot-7 (he was likely around 5-foot-5), Marrero insisted he had no desire to head to the big leagues and therefore pitch away from his Cuban home.

The team celebrated “Marrero Night” that year, but by 1950 the Senators convinced Marrero to give the big leagues a try. Legendary scout Joe Cambria signed Marrero to a contract worth $6,500.

“Almost anything will help our pitching,” Senators manager Bucky Harris told the Miami News in the spring of 1950, “and (Marrero) might be of some benefit here and there.”

The Senators were 50-104 in 1949, finishing last in the American League and posting a team ERA of 5.10. Harris took over as manager again in 1950 (he had managed the team from 1924-28 and 1935-42) and improved the team’s win total by 17 games.

Marrero found a role as a spot starter/reliever, debuting on April 21 against the Yankees in a mop-up relief role. Six days later, Marrero pitched seven shutout innings in relief against the Athletics, allowing four hits and no walks.

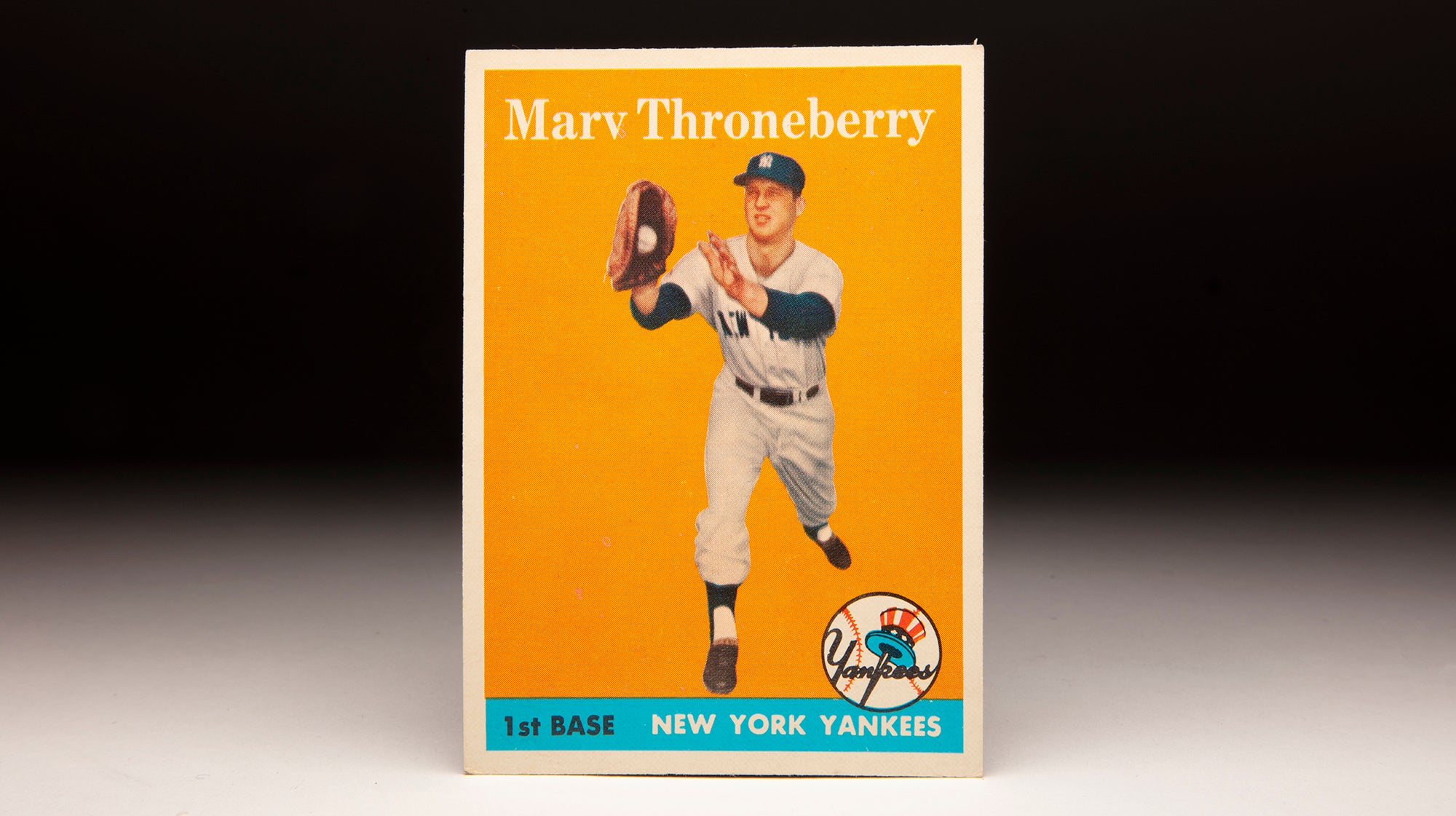

Many outlets reported that Marrero was just 33 years old, knocking six years off his actual age. His 1953 Topps card gave his birthday at May 1, 1915.

Marrero made his first start on May 7, picked up his first win with 7.2 innings of one-run relief against the White Sox on May 10 and pitched a complete game against the Tigers on May 21.

He finished the 1950 season with a shutout of the Red Sox on Sept. 27, going 6-10 overall with a 4.50 ERA in 152 innings of work.

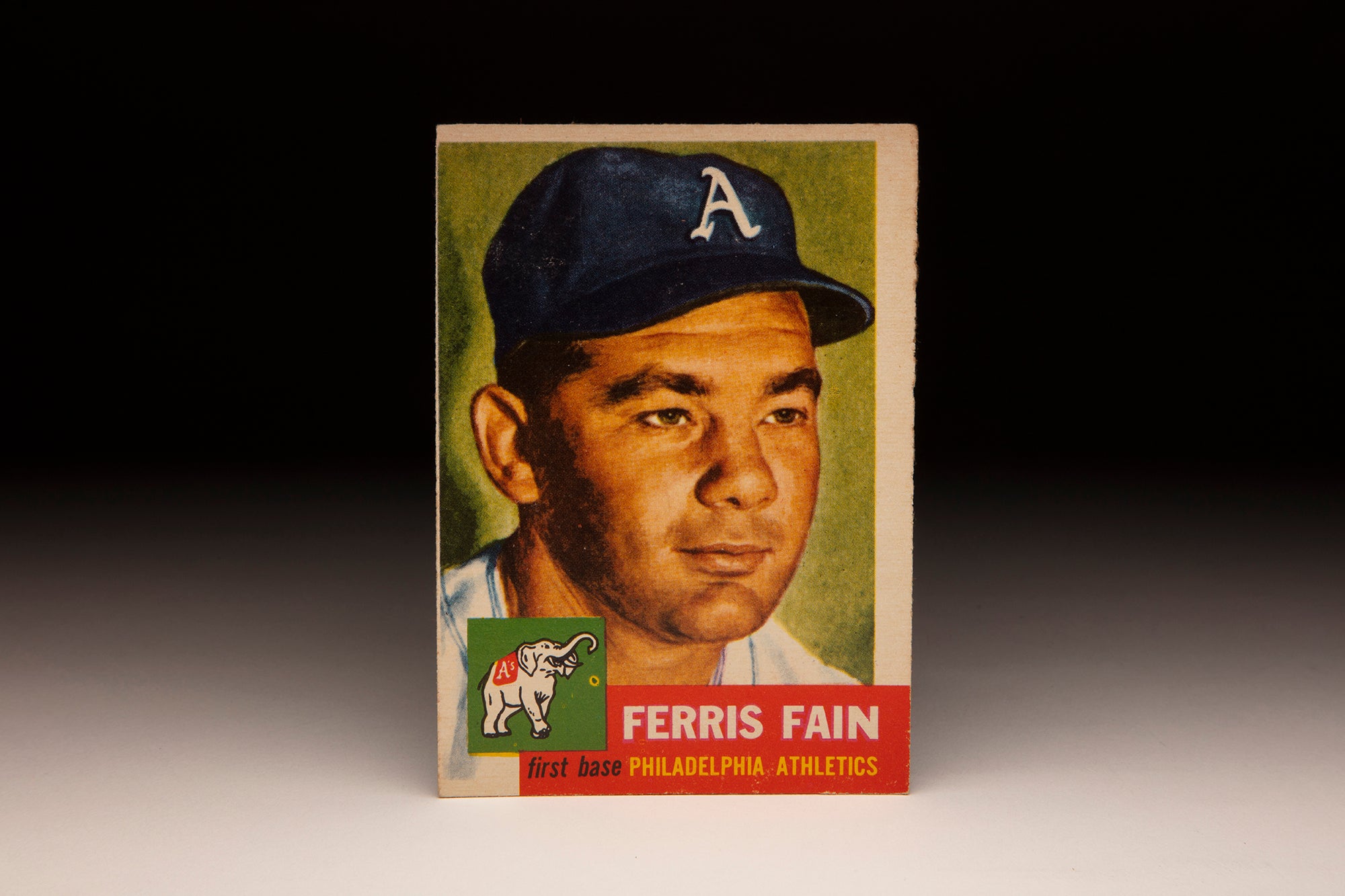

Marrero, who by now was being called “Connie” by the press, was named the Senators’ Opening Day starter in 1951 and pitched a complete game seven-hitter, allowing only one run in the ninth inning in Washington’s 6-1 win over the Athletics. Nine days later, Marrero again went the distance against the A’s, allowing only one hit – a fourth-inning home run by Barney McCoskey – in a 2-1 victory that moved the Senators into a first-place tie in the American League.

“He keeps the team in a good humor,” Harris said of Marrero to the Associated Press, “and his humor is never misplaced.”

Marrero notched complete games in eight of his first nine starts in 1951, sprinting out to a 6-1 record before the workload began to wear on his aging arm. He was 11-5 following a three-hit shutout of the White Sox on Aug. 4, but did not win again that year – finishing 11-9 with a 3.90 ERA (up from 3.14 after the shutout of the White Sox) in 25 starts covering 187 innings.

His 16 complete games were the most by a pitcher in his 40s since Ted Lyons notched 20 in 1942.

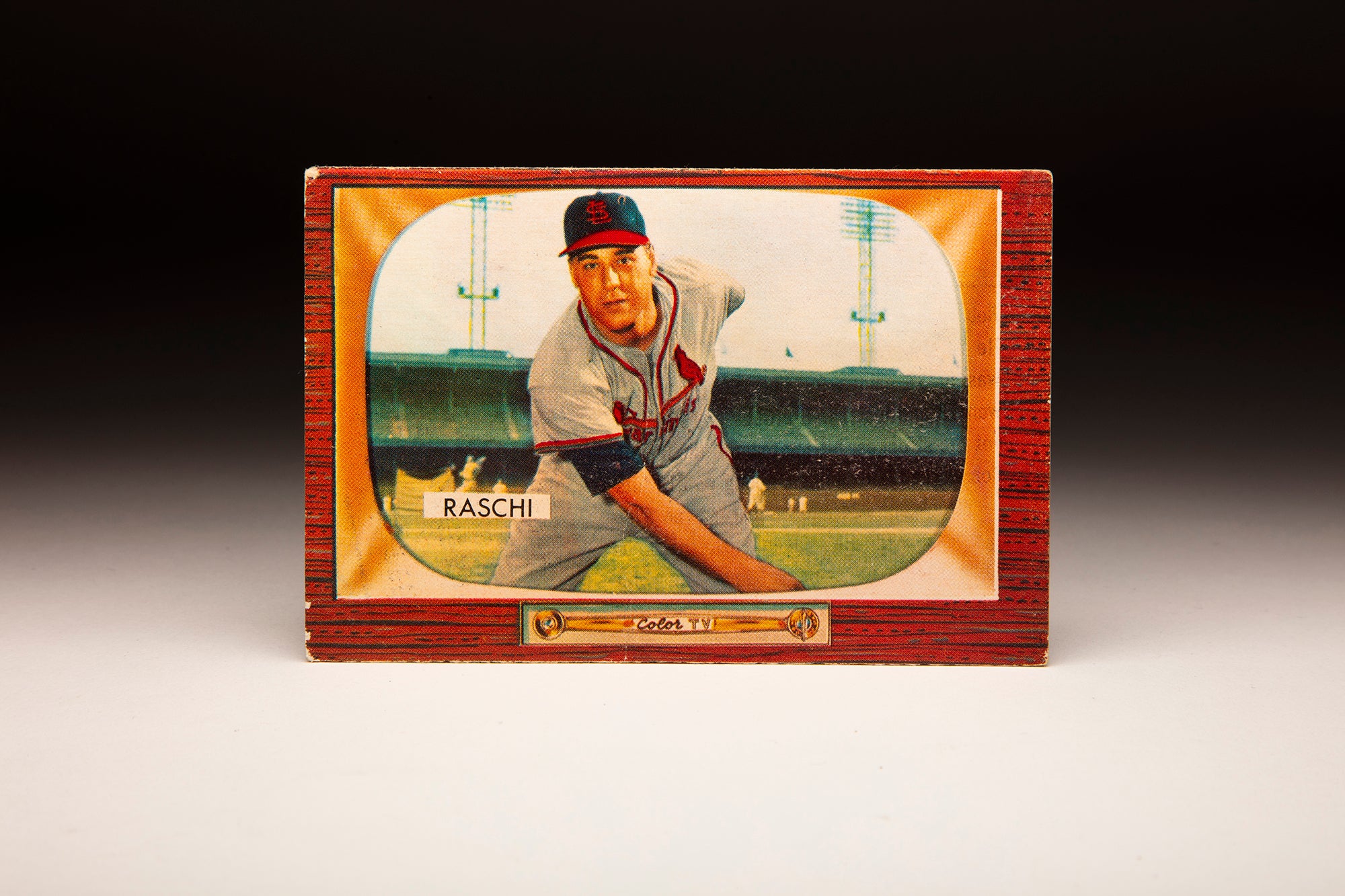

On June 26, 1951, Marrero pitched a complete game against the Yankees, allowing three runs in a 7-3 Washington victory. It would mark one of two times Marrero faced Joe DiMaggio, who Marrero said was the “perfect player, perfect in everything he did.”

Marrero fanned DiMaggio, who was making a pinch-hitting appearance that day.

Marrero began the 1952 season on another hot streak, going 7-2 in his first 10 starts – all but one of which was a complete game. Working about once a week, Marrero went 11-8 with a 2.88 ERA over 184.1 innings – with another 16 complete games.

Among Live Ball Era (post 1919) pitchers who were at least 40 years of age, only Marrero, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Warren Spahn and Lyons had at least two seasons with at least 15 complete games.

In 1953, Marrero – now 42 – recorded complete games in five of his first eight starts as Harris continued to give his pitcher ample rest between starts. But he once again cooled off as the season wore on, finishing 8-7 with a 3.03 ERA in 20 starts. For the third year in a row, Marrero posted exactly two shutouts – each year blanking the Browns once and the White Sox once.

Marrero usually had better luck against weaker teams, working to an 8-3 record with a 1.50 ERA in 14 career games vs. the Browns, for example, while going 4-11 with a 4.79 ERA in 19 outings against the Red Sox.

But his age also clearly factored into that equation: In games prior to the All-Star Game in each of his five big league seasons, Marrero was 27-18 with a 3.33 ERA. After the Mid-Summer Classic, he was 12-22 with a 4.08 ERA.

Harris moved Marrero to the bullpen in 1954, and Marrero did not fare well – going 3-6 with a 4.75 ERA in 22 appearances, including eight spot starts. Following the season, the Senators attempted to option Marrero to the minors before eventually releasing him on Jan. 15, 1955.

Marrero, however, returned to Havana and signed on with the Sugar Kings of the International League. On a team that featured a host of big league talent like Yo-Yo Davalillo, Clint Hartung and Ken Raffensberger, Marrero was 7-3 with a 2.69 ERA in 16 starts.

Marrero made appearances for the Sugar Kings in each of the next two seasons before retiring as an active player. He worked as a scout for the Red Sox before the Cuban Revolution cut off the talent pipeline to the big leagues. He then served as Minister of Sports for the Castro government in his retirement.

On March 28, 1999, Marrero threw out the first pitch of the Baltimore Orioles vs. Cuban National Team exhibition game at Estadio Latinamericano in Havana. Marrero tossed eight pitches to Baltimore’s Brady Anderson before being led off the mound.

“For me, this is special,” the 87-year-old Marrero told the New York Daily News. “I have not seen a major league team in 40 years. I stayed here because my parents were here and they were old. I never made much money playing baseball -- $6,500 my first year with the Senators to a top salary of $18,000.

“Baseball is my life. It’s in my soul.”

Through efforts of the Baseball Assistance Team and others, Marrero – who had been advised by teammates not to enroll in the MLB pension program – received support payments totaling $40,000 in the final years of his life.

Blind for the final few years of his life following an unsuccessful cataract operation, Marrero was a revered figure in Cuba and held the title of the oldest living former major leaguer for several years before he passed away at the age of 102 on April 23, 2014 – two days before a planned national celebration that was to honor his 103rd birthday.

Marrero posted a 39-40 record with a 3.67 ERA over five big league seasons, working 574.1 innings after he turned 40 years old. No 40-year-old pitcher worked more innings in the 1950s.

“He could throw a ball in a tea cup,” said Hall of Famer Tommy Lasorda, who saw Marrero in International League games in the late 1950s. “That’s the kind of control he had.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum