- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1967 Topps George Altman

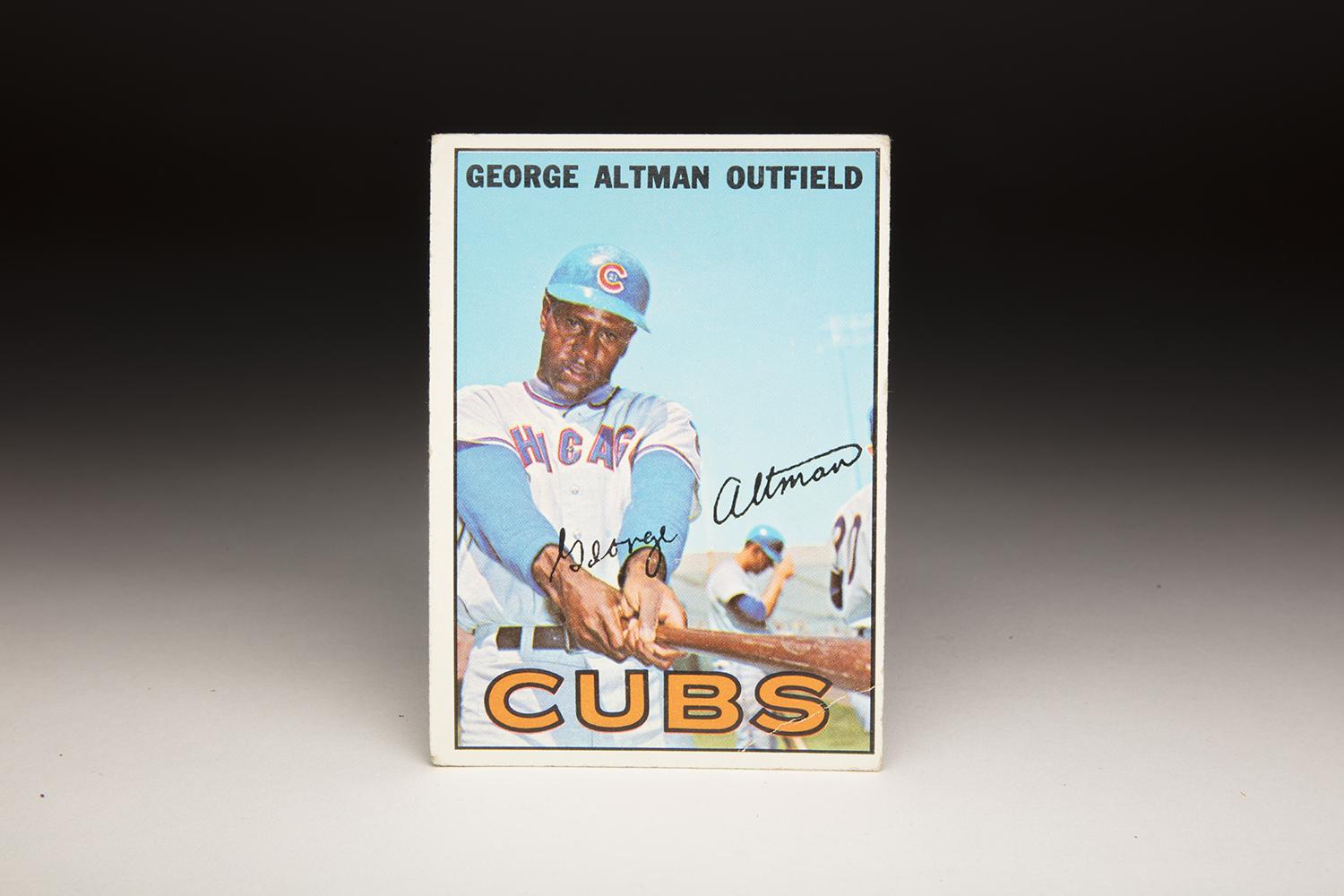

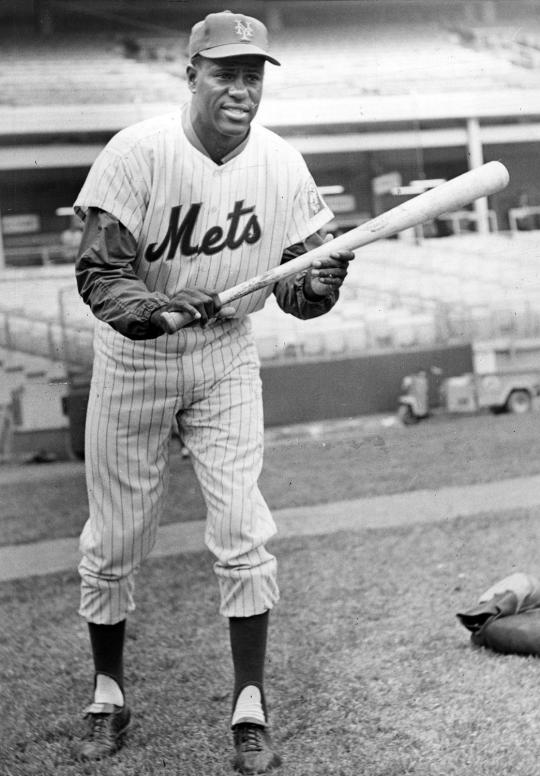

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps George Altman

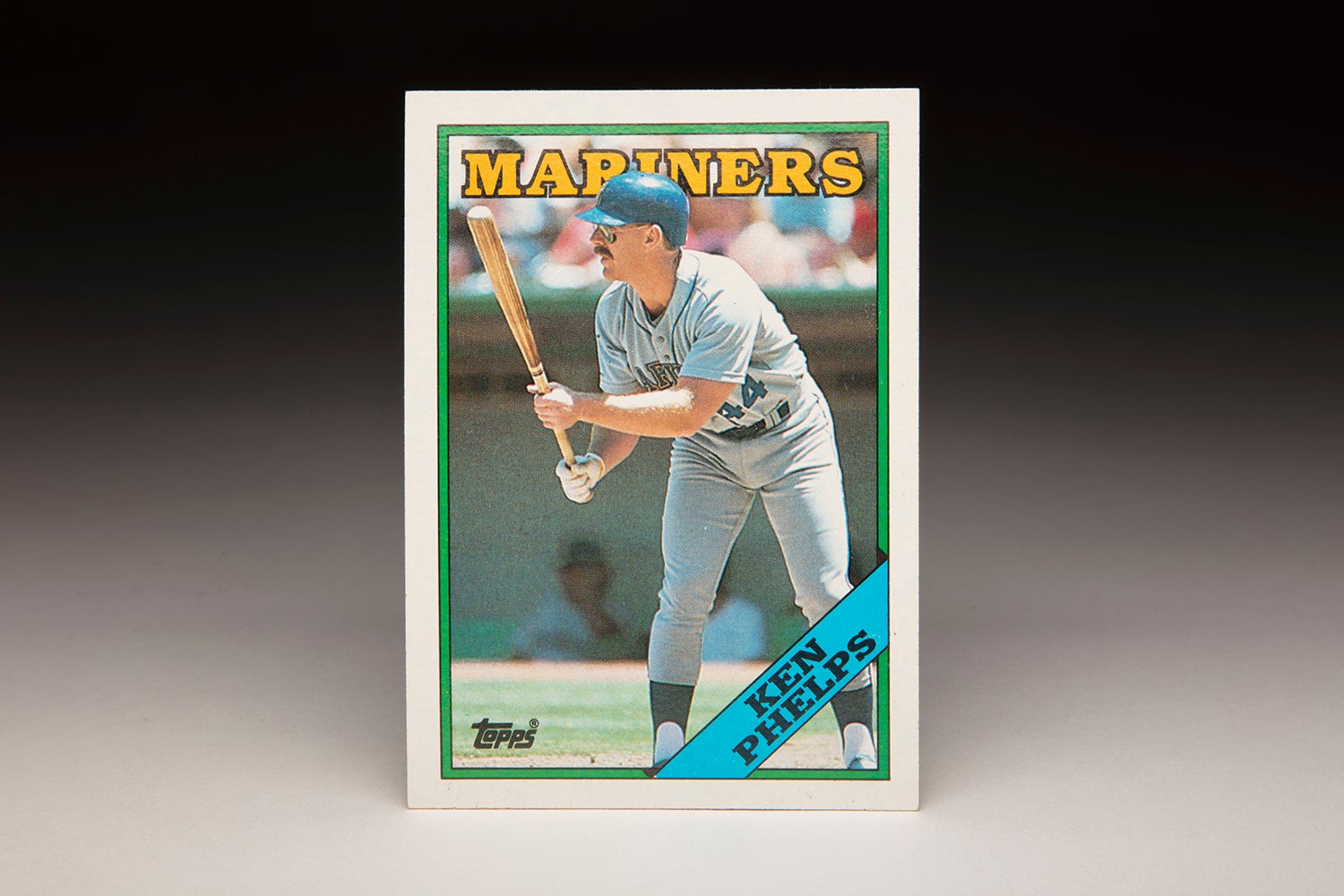

For a whole host of reasons, I like cards from the 1960s. Topps tended to print the cards on thicker stock, making them hold up better over the long haul. The photos, while lacking in action shots, are generally of good quality, giving us accurate close-ups of the players during their youthful days in the big leagues.

For me, two of the features that stand out on a number of Topps cards from this era are on full display in the 1967 card of George Altman. First, the photograph was taken during a pregame workout, which gives us a gander at a few other ballplayers in the background. It can be fun to try to figure out who the players are, based on their physical features or their uniform numbers. In this case, two of Altman’s teammates with the Chicago Cubs make cameos here. One of the players appears to be wearing No. 20. If that’s accurate, then it would be backup outfielder Ty Cline, who played in only seven games for the Cubs in 1966. The other player, who is donning a helmet, is more difficult to determine. He appears to be relatively thin, so perhaps it’s Glenn Beckert or Don Kessinger, both of whom were lean types, but those are merely wild guesses.

Second, Topps photographed many of its cards from the 1960s at Spring Training, either in Florida or in Arizona. Spring Training shots tend to give us sunny backgrounds, which can be a nice change of pace from the dreariness of the long winter, when we start collecting cards each year. With the sun comes the blue sky background, which only adds to the color and vibrancy of the card.

On the Altman card, the blue sky is enhanced by the blue helmet and the similarly blue sleeves of the Cubs’ uniform. The bright blue tones pop out at you, overwhelming the card and making it stand out among the 1967s.

Altman completes the card by giving us one of those patented fake swings, a maneuver commonly seen on cards from the 1960s and 70s. It’s a contrived pose, I know, and one that looks awkward given how Altman is holding the bat near his belt, but I like this old-fashioned posture on a card. I especially like how the barrel of the bat seems to be piercing the frame of the card. Call me corny, call me hopelessly old school, but fake swings like this give cards a vintage feel from a simpler time.

For a while, George Altman had one of the most feared swings in the National League. Over the span of two consecutive seasons, he made the All-Star team while putting together a delightful mix of speed and power. As a left-handed power hitter of extra-large dimensions (6-foot-4 and more than 200 pounds), Big George had the kind of build and swing that intimidated opposition pitchers.

The story of Altman’s professional career did not begin in the National League, but rather in the Negro Leagues. In the mid-1950s, Altman received a tryout with the Kansas City Monarchs, one of the most successful and storied of the Negro leagues franchises. The young outfielder impressed at the tryout, earning a spot on the Monarchs’ roster in 1955. That gave him the opportunity to play for legendary manager Buck O’Neil, who promptly taught the right-handed throwing Altman how to play first base. O’Neil provided insight on proper footwork around the bag, how to stretch for throws, and how to handle the fundamentals of the position.

Altman played only three months with the Monarchs, not because they wanted him off the team, but because of burgeoning interest from MLB scouts. Based on O’Neil’s recommendation, the Chicago Cubs signed Altman and two other Monarchs, while giving Kansas City $11,000 as compensation. Just like that, Altman was part of Organized Ball, slated to report to the Class B Burlington Bees in 1956.

It turned out to be a difficult rookie season in the Cubs’ farm system. At road games, Altman heard racial insults from fans. As one of the few black players on the Burlington roster, Altman felt somewhat awkward and out of place. None of the Bees openly mistreated Altman, but like many African-American players of the era, he felt like he was living on an island.

Altman hit 16 home runs for Burlington, priming himself for a promotion in 1957. Then came an unexpected delivery in the mail: A draft notice informing him of a military assignment to Fort Carson in Colorado. As a result, Altman missed all of the 1957 season, but his military tenure still allowed him to play both baseball and basketball on the base. The Army experience actually helped Altman, giving him the chance to play with several big league players, including Willie Kirkland and Leon Wagner.

His military duty fulfilled, Altman continued his minor league career in 1958. Moving up to Class A ball, Altman hit 14 home runs, legged out 11 triples and batted a cool .325. The Cubs liked what they saw of Altman and his unusual combination of power and speed.

After playing winter ball in Panama, Altman reported to the Cubs’ Spring Training camp in 1959. Few expected him to make the team, but he played so well in exhibition games that he drew praise from famous observers like Rogers Hornsby and Ty Cobb. In particular, Cobb liked Altman’s knowledge of the strike zone and his ability to hit with power to all fields. Cubs management was equally impressed and opted to trade veteran outfielder Chuck Tanner, thereby opening up a spot for Altman.

Altman had played largely as a first baseman, but Cubs manager Bob Scheffing felt that he belonged in center field, where he could use his footspeed. The Opening Day center fielder, Altman held onto the job all season long, aside from a brief benching in midsummer. His numbers weren’t great – he batted .245 with 80 strikeouts – but likely would have been better if not for a broken finger he suffered while making a diving catch in center field. He also learned a great deal about the big league culture and the realities of racism, thanks to a pairing with roommate Tony Taylor, a Cuban American who also happened to be black.

In his second season, Altman adjusted to a new role. The wintertime acquisition of Richie Ashburn forced Altman into becoming a part-time player, performing as a rotating outfielder and backup first baseman. When Altman did play, he improved his hitting, cutting down his strikeouts and lifting his batting average to .266. With an OPS nearly 100 points higher than his rookie year, Altman showed real progress against National League pitching.

By 1961, Altman was ready for a breakthrough. The Cubs moved him to right field, a more comfortable position for him to play. At the plate, Altman bloomed, hitting .303 with 27 home runs, slugging .560, and leading the league in triples with 12. Not only did Altman earn a berth on the All-Star team, but he also placed 14th in the National League’s MVP balloting.

In 1962, Altman played just as well, even as he suffered a sprained wrist in midseason. His power dropped off a bit, but he increased his batting average to .318 and added the stolen base to his arsenal. With 19 steals and 22 home runs, he became the only Cub to reach double figures in both categories. On a Cubs team that won only 59 games, Altman stood out as one of the few lynchpins. He also enjoyed a reunion with Buck O’Neil, who joined the Cubs’ College of Coaches that season.

Still only 29 years old, Altman seemed like he would remain a part of the Cubs’ nucleus for several years to come. With two All-Star Game nods in two seasons, his status with the Cubs seemed safe. That’s why Altman was somewhat surprised to hear the news of Oct. 17, only a few weeks after the end of the regular season. On that day, the Cubs dealt Altman to the rival St. Lous Cardinals for pitchers Larry Jackson and Lindy McDaniel and backup catcher Jimmie Schaffer.

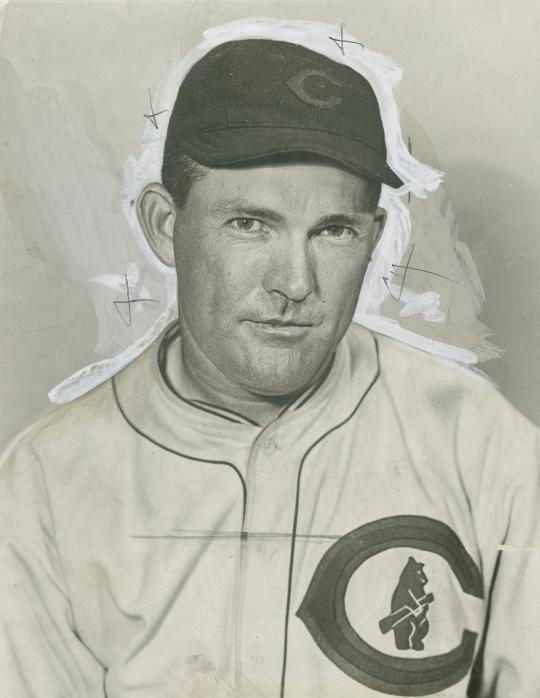

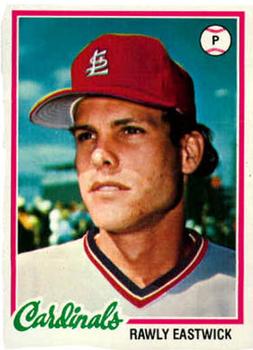

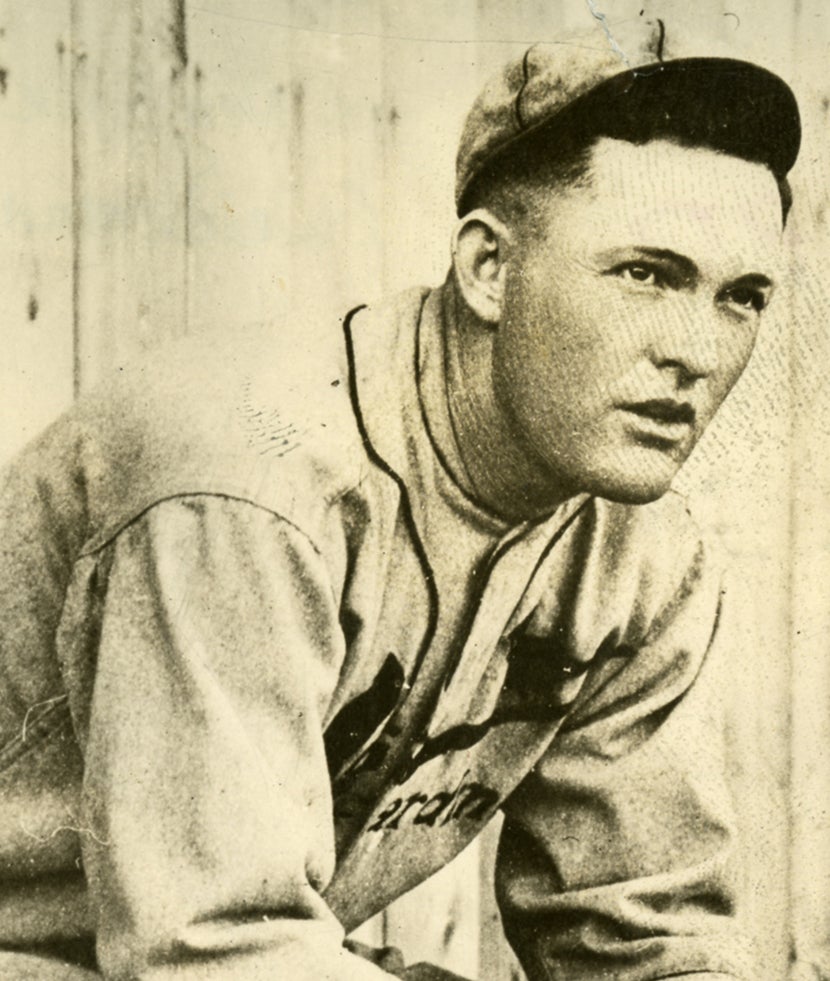

Buck O'Neil (pictured above) was manager of the Kansas City Monarchs when George Altman made the team in 1955. He taught Altman the proper fundamentals of playing first base, and was reunited with him years later when Altman joined the Chicago Cubs. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

The trade did not sit well with Altman, but he did his best to remain philosophical about the move to St. Louis.

“I hate to leave Chicago and the Cubs,” Altman told writer John Kuenster, “but you accept being traded as an occupational hazard.”

Once the initial sting wore off, Altman realized that he would be playing for a better team. The Cardinals would win 93 games in 1963, but Altman’s performance resulted in disappointment. By his own admission, he tried to take advantage of the short right field porch at Sportsman’s Park by pulling everything, rather than use his natural power to all fields. Both his batting average and his home run output suffered. He hit .274 with nine home runs, a far cry from his two All-Star seasons in Chicago.

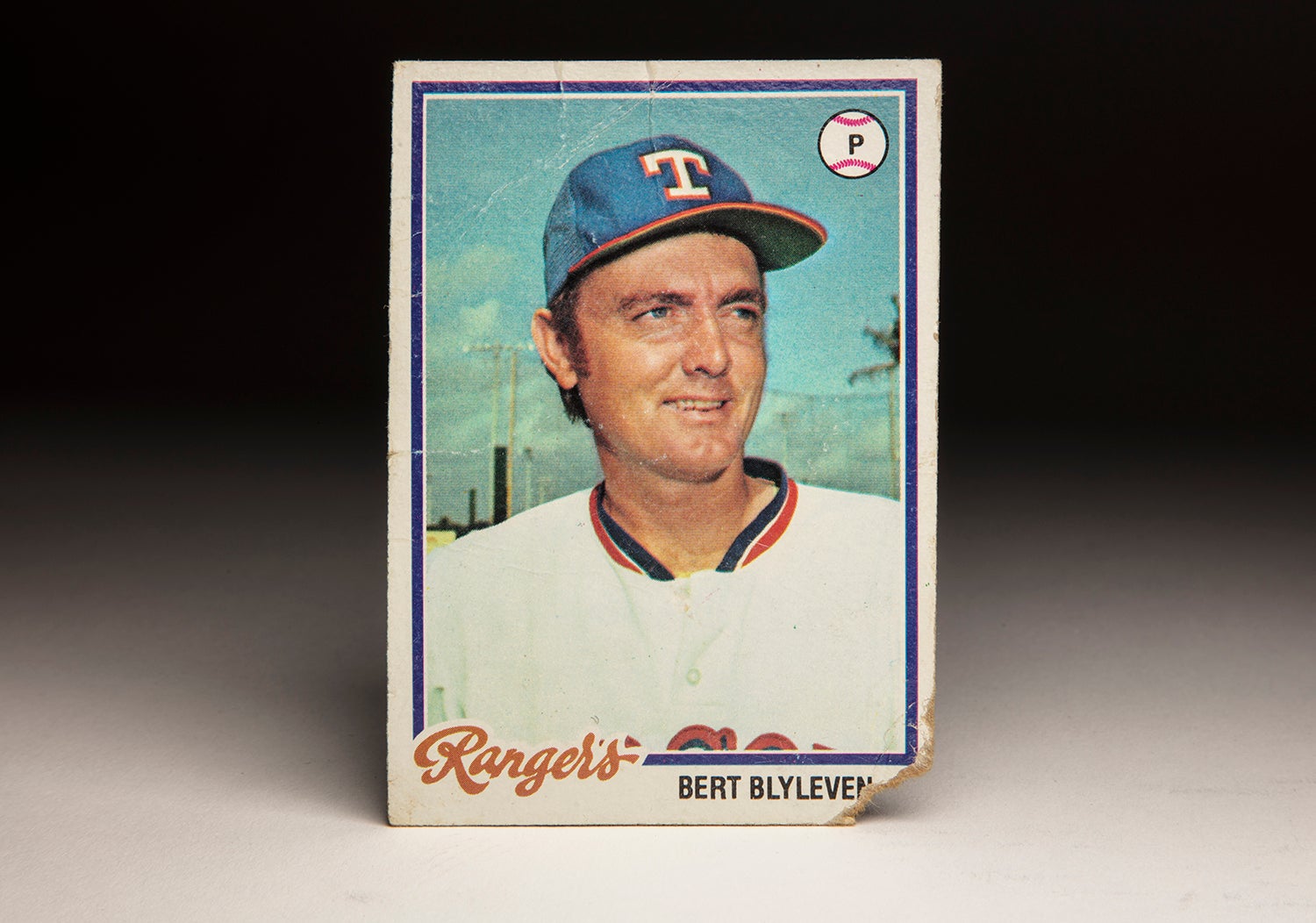

Disappointed by their new slugger, who was now 30 years old, the Cardinals decided to trade Altman for pitching. In November, they sent him to the New York Mets for veteran right-hander Roger Craig. With the Mets, Altman put up identical home run and RBI numbers to what he had done in St. Louis, but his batting average dropped like a sinking fastball. He batted .230, the worst mark of his career.

Not surprisingly, Altman’s subpar numbers placed him on the trade market. For the third straight winter, Altman saw his address change. In January of 1965, the Mets traded him back to the Cubs for journeyman outfielder Billy Cowan (whom we profiled in one of our earliest Card Corners). It was a trade that signaled how far Altman’s stock had fallen.

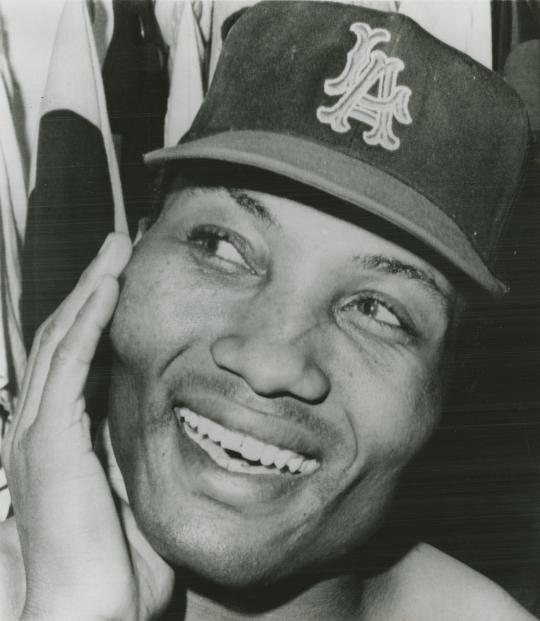

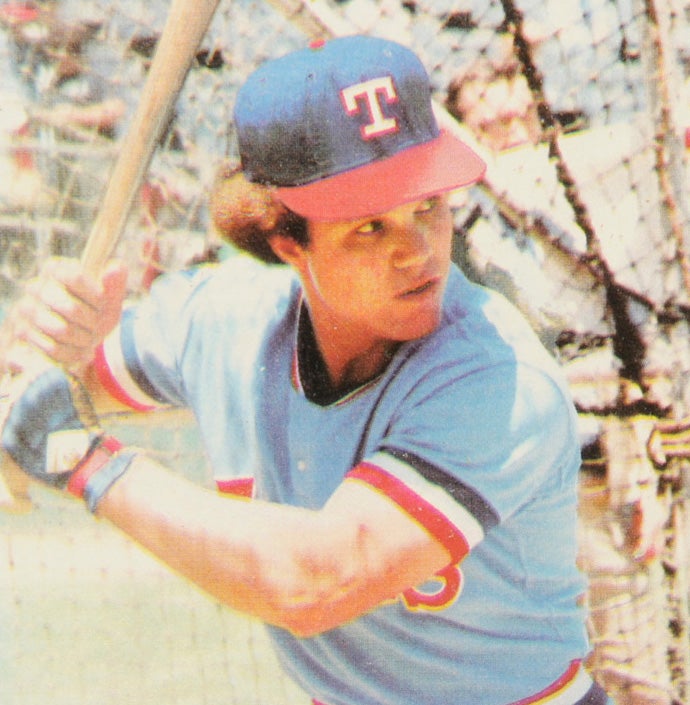

George Altman joined the Chicago Cubs in 1959, and would play with them for seven seasons in total. Pictured above with his teammates in 1959 (L to R): manager Bob Scheffing, Tony Taylor, George Altman, Ernie Banks, Walt Moryn, Earl Averill, Dale Long, Bobby Thomson and Sammy Taylor. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Altman began the 1965 season as the Cubs’ left fielder, rapping out three hits on Opening Day, but eventually lost his starting spot. He then spent the next two summers playing a bench role, where manager Leo Durocher showed a preference for using younger players. In 1967, Altman endured a demotion to Triple-A ball. Convinced that he could still play every day in something other than the minor leagues, Altman asked for his unconditional release, which the Cubs granted him later that season. So Altman took his talents to the Japanese Leagues. That’s why the 1967 card is the last one that Topps produced for the veteran slugger.

Now 34 years old, Altman seemed past his prime. But the Tokyo Giants offered him a one-year contract that matched the terms of his deal with the Cubs. It quickly paid off; Altman hit .320 with 34 home runs, making himself a certified star in Japan. He also began to adjust to the Asian culture, including the Japanese preference for hot baths. “I lost 18 pounds during the first season in Japan largely because I used to follow my teammates into the baths after games,” Altman explained to sportswriter Norman Pearlstine.

At season’s end, the shrinking Altman became a free agent, but chose to remain in Japan. This time he signed a long-term deal with the Lotte Orions. The deal turned out wonderfully – for both the Orions and for Altman. For the next six seasons, Altman put up massive numbers, consistently hitting over .300 and putting up 20-plus home runs.

In 1974, Altman was on pace for his best season in Japan, posting an OPS of 1.095 through the three-quarter pole of the season, when he was diagnosed with colon cancer. Altman had to undergo chemotherapy, weakening him substantially. Remarkably, Altman did not allow the disease to end his career; he came back for one more season in 1975, playing respectably for the Hanshin Tigers at the age of 42.

By the end of his final season, the well-liked Altman had become a legendary figure in Japan. Fans became obsessed with him, not only because of his power hitting, but because of his sheer size. “Fans would follow me around like a freak,” Altman told Chicago Cubs Vineline in 1987.

Having extracted all that he could from his large, well-conditioned body, Altman went on to find success in another field. Given his intelligence and his communications skills, that should have come as no surprise. Altman became a commodities trader for 13 years, specializing in the trading of wheat and soybeans.

In retirement, Altman made numerous public appearances, including a role as the 2016 keynote speaker for the Society for American Baseball Research’s Jerry Malloy Conference, where he regaled SABR members with stories of the Negro Leagues. He passed away on Nov. 24, 2025.

In many ways, Altman’s life was one of remarkable resilience. When it appeared that his MLB days had ended, he sprouted a second career as a Japanese legend. When cancer struck, he found a way to keep playing. Even after baseball, Altman excelled in the world of finance.

It seems that George Altman kept finding the bright blue skies of his 1967 Topps card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum