- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Greg Goossen

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Greg Goossen

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

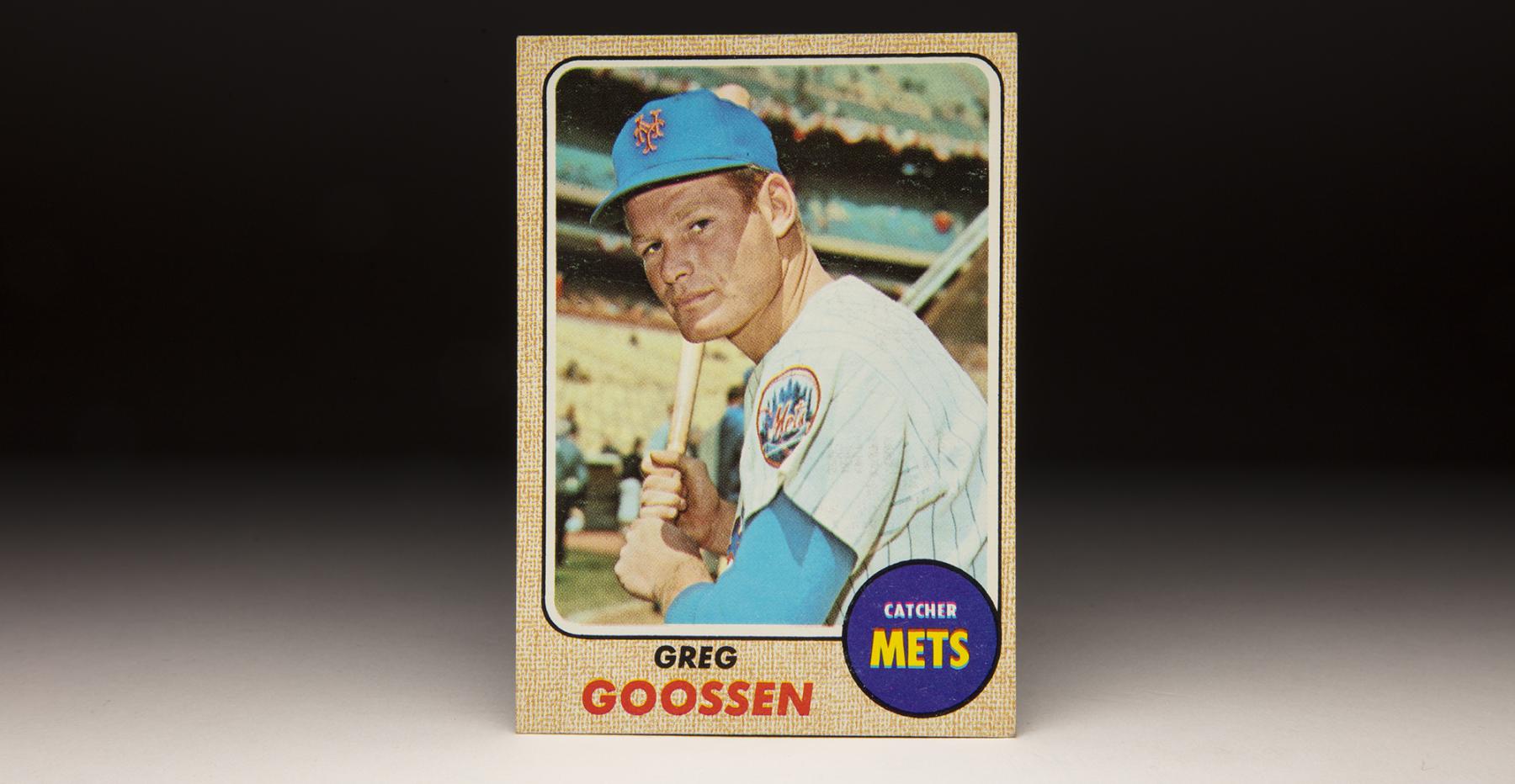

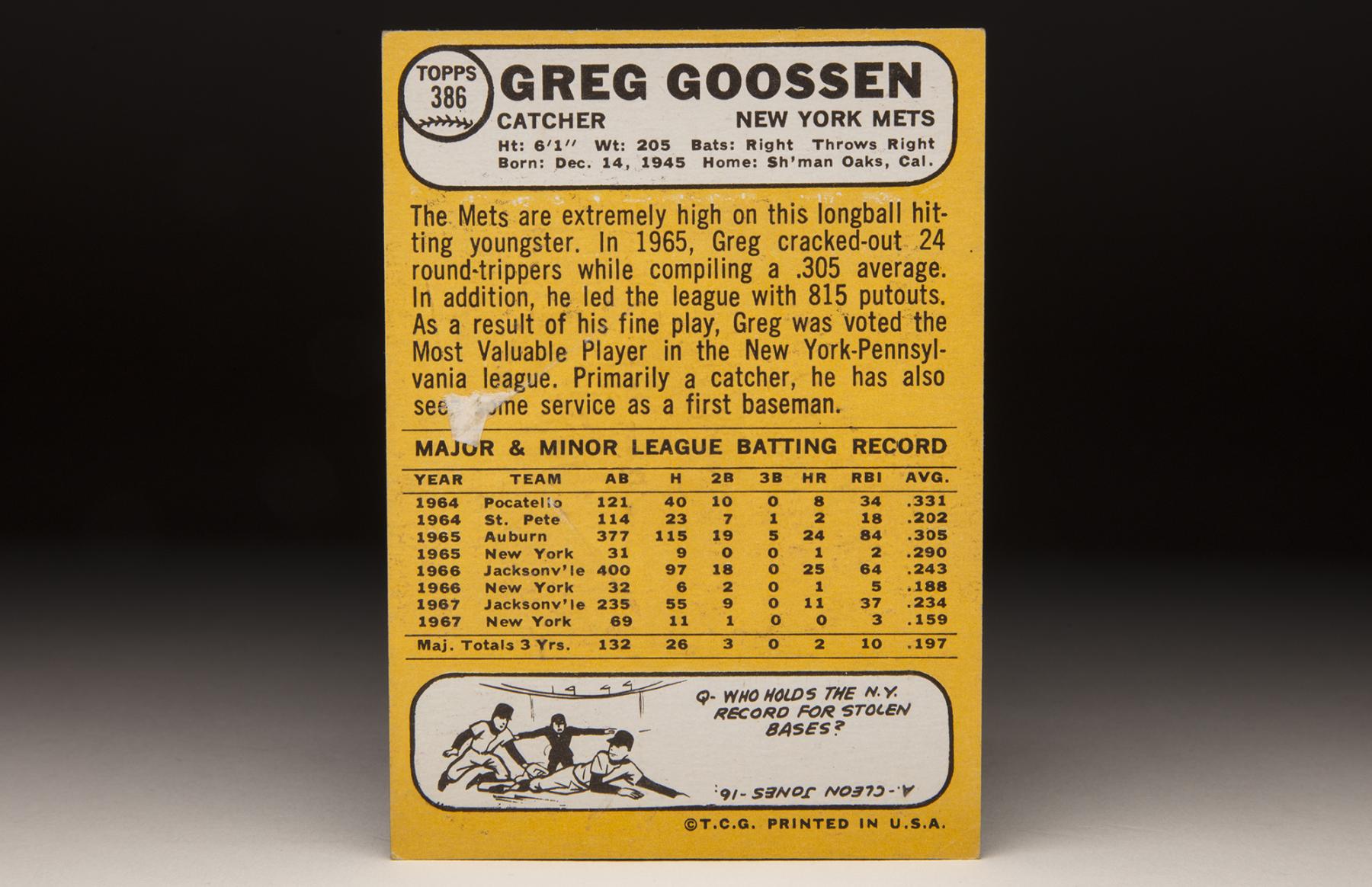

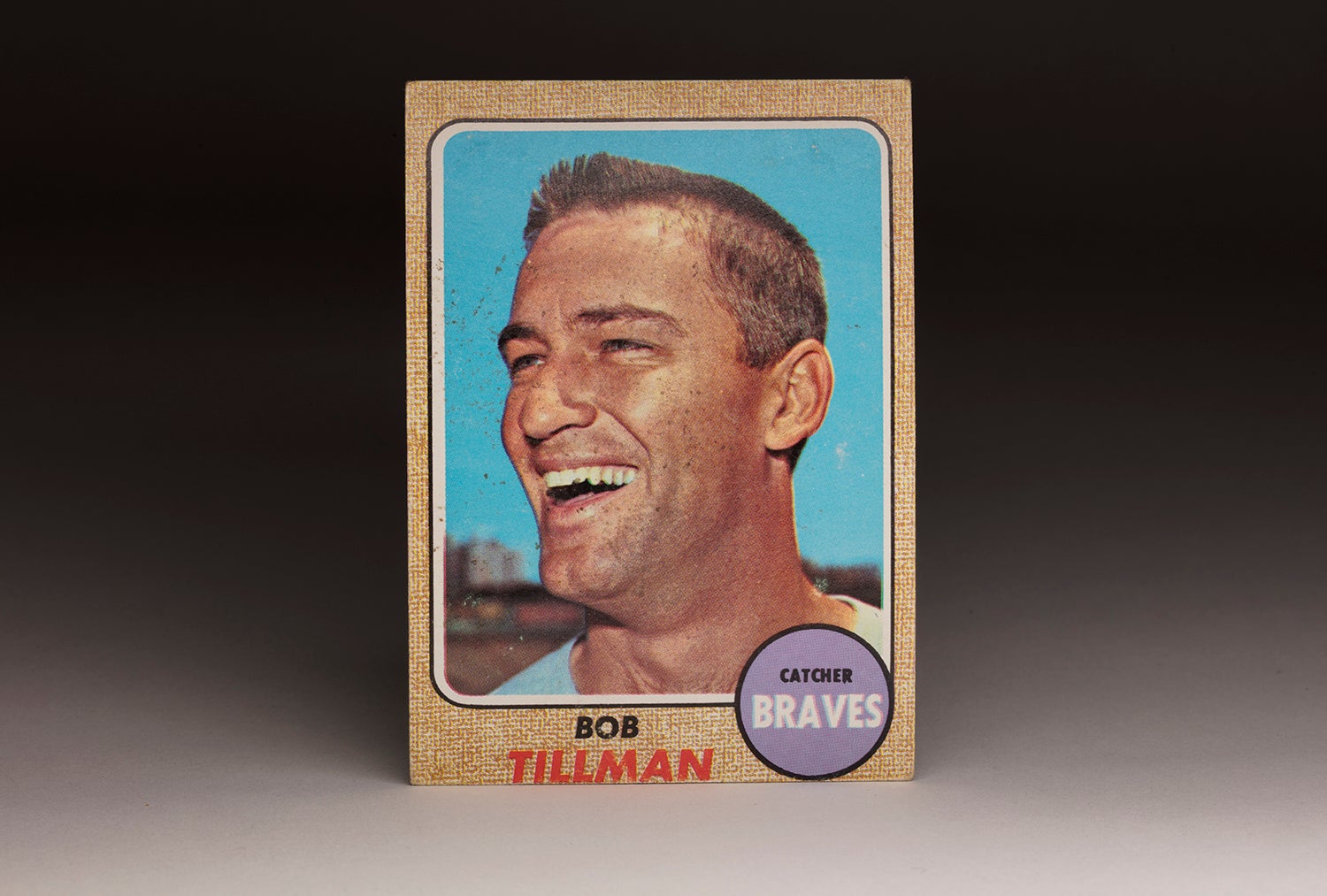

Greg Goossen appeared on only three Topps cards during his abbreviated major league career: His 1967 rookie card, a 1968 selection and a 1970 card. Of the three, he appeared twice as a member of the New York Mets.

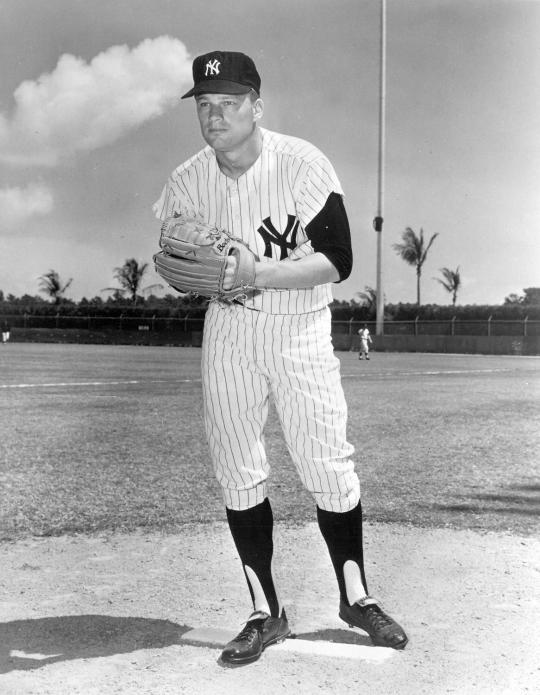

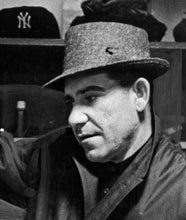

He had to share his rookie card with a shortstop named Bart Shirley, but in 1968 he was given a card all to himself. It’s a nice posed shot from Shea Stadium that shows off the bright blue pinstripes of the Mets. And it’s as a Met that most of us will remember Greg Goossen.

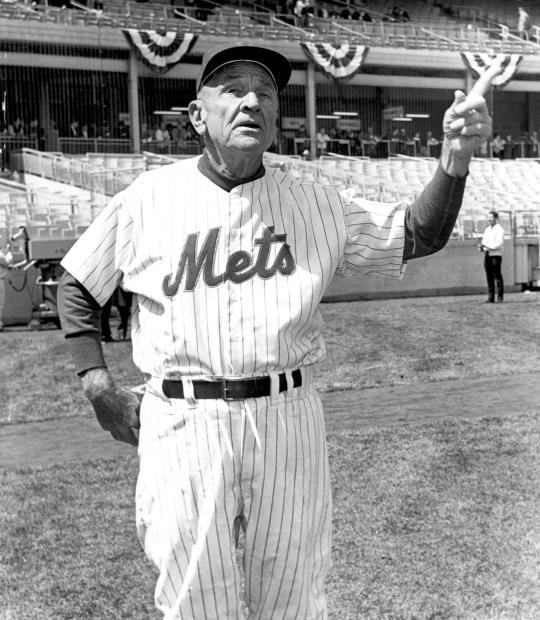

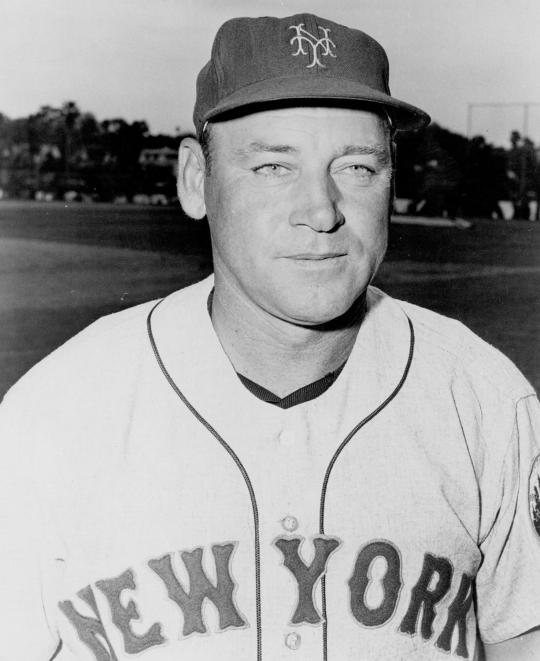

It was while he was with the Mets in 1965 that Goossen unwittingly provided the impetus for one of the greatest quotations every uttered by Casey Stengel. Goossen was spending his first Spring Training with the Mets, who performed their workouts and played their home games in St. Petersburg, Fla. Goossen struggled that spring, with his less-than-adequate catching skills on full display. When a Mets beat writer approached Stengel for his opinion on the young catching prospect, “Ole Case” provided the following assessment:

“This is Greg Goossen. He’s 19 years old, and in 10 years, he’s got a chance to be 29.”

Hardly a ringing endorsement, Stengel’s words provided a few chuckles during that training camp. It was the kind of remark that a manager would never utter in today’s game, where managers rarely offer public criticism of players, and even more rarely issue a comically-tinged insult of a young prospect. But it was exactly the kind of remark that the brutally honest Stengel would make; he could be particularly blunt, especially in an era where managers were regarded as the boss and the players were clearly seen as their underlings.

Somehow, Stengel’s putdown did not seem to bother Goossen. In fact, he loved to tell friends the story, with all of its humorous overtones, about the Stengel remark. In some ways, Goossen treated the Stengel jab as a badge of honor.

Other than his Mets uniform, Goossen’s appearance on 1968 Topps is notable because of his physical appearance. With his lantern jaw, blonde hair, broad shoulders and muscular build, Goossen had the look that directors and producers in Hollywood crave. If he didn’t play baseball for a living, he might have been an actor.

In fact, Goossen did become an actor, or at least sort of. Many years later, after his playing days ended, Goossen took on a career as a stand-in for legendary actor Gene Hackman, who became fast friends with the former ballplayer. While Goossen didn’t really look like Hackman, he didn’t have to in order to be a stand-in. A stand-in is not the same as a body double or a stunt double; he doesn’t appear on camera, but is used to set up lighting and camera angles. Stand-ins just have to have similar skin tone, height, and weight to the actors in question. Goossen qualified on all counts.

Goossen happened to meet Hackman while working at a Southern California gymnasium in 1988. Goossen’s brother, Joe, asked him to meet with Hackman, who was looking for background information that would help him on a boxing film called Split Decisions. Goossen happily provided Hackman with research assistance, the two men becoming fast friends. Hackman liked him so much that on Goossen’s 60th birthday, he gave him a special token of appreciation: A brand new Mercedes.

Hackman also had it written into all of his subsequent film contracts that Goossen would serve as his stand-in. In addition to the stand-in work, Goossen also made brief appearances in 15 of Hackman’s films, including some of his best: The Package, Class Action, Get Shorty and Unforgiven.

Appropriately enough, Goossen started his baseball career in 1964 by signing with Hollywood’s team, the Los Angeles Dodgers. Highly touted as a right-handed slugger, Goossen received a six-figure bonus. He spent the 1964 season in the Dodgers’ farm system, but the rules of the day dictated that he could be taken in a first-year waiver draft at season’s end. Sure enough, the expansion Mets took Goossen in the waiver draft and brought him to Spring Training in ‘65.

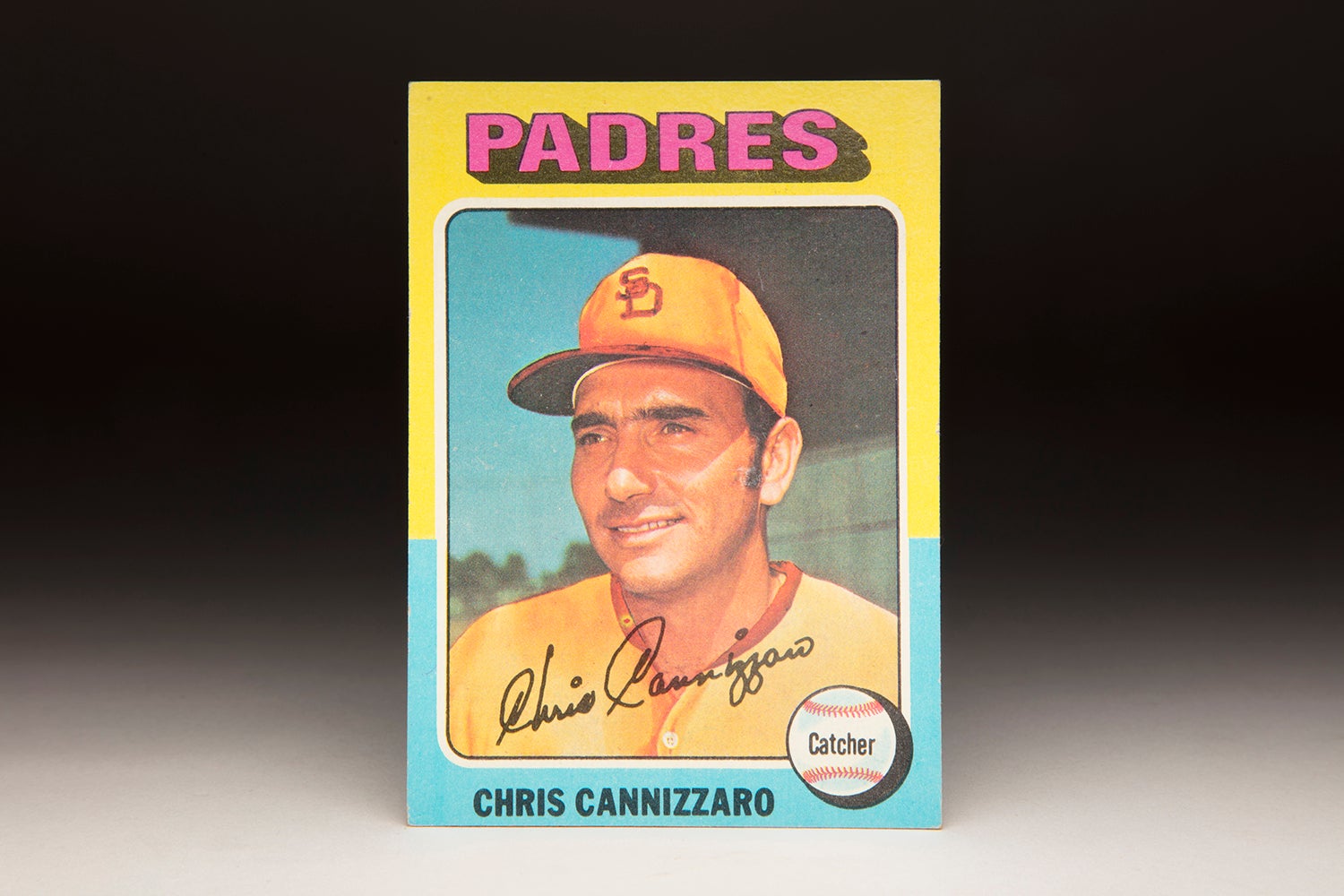

The Mets assigned Goossen to Auburn, their affiliate in the Class A New York-Penn League. Goossen moved up quickly; by season’s end, he found himself in New York playing for a Mets team that badly needed help at catcher. At one point, the Mets had activated a 40-year-old Yogi Berra, who had last played in the majors in 1963. They had also given look-sees to players like Chris Cannizzaro, Jesse Gonder and John Stephenson, but none brought the potential of power hitting that came with Goossen.

In 31 late-season at-bats, Goossen hit well, putting up a .290 average. He also showed improvement behind the plate. “The fellow handles himself like a pro,” manager Wes Westrum told sportswriter Barney Kremenko. “He has a strong arm. He calls a good game. He talks to the pitcher. He backs up all the players.”

On the strength of his all-around performance, the Mets included Goossen on their Opening Day roster in 1966. Unfortunately, his play regressed. Goossen struggled in April and May, so much so that the Mets sent him back to the minor leagues. Playing at Triple-A Jacksonville, he split his time as a catcher, first baseman and outfielder.

Over the next two seasons, Goossen shuttled back and forth between Jacksonville and New York. In limited major league duty, he struggled to find his batting stroke. His defensive play also became spotty. One of the few offensive highlights came on May 31, 1968, when the Mets were being shut down by the Cardinals’ Larry Jaster. With a perfect game intact in the bottom of the eighth inning, Goossen came to the plate and rippled a clean single, ending the bid at perfection.

Goossen hoped to compete for a job with the Mets in the spring of 1969, but a preseason trade changed all of that. In February, the Mets dealt Goossen to the Seattle Pilots – one of the two new expansion teams in the American League – for outfielder Jim Gosger.

The trade turned out to be a mixed blessing. On the one hand, it denied Goossen a shot at winning a world championship with the Mets in 1969. But there was good news. After starting the season at Triple-A Vancouver, Goossen received a chance to play in Seattle.

The Pilots no longer viewed Goossen as a catcher, a position where he had continued to struggle, but felt that he might be able to contribute as a first baseman/outfielder. Beginning on July 25, he did exactly that. In 157 plate appearances, he batted .309 with a .597 slugging percentage.

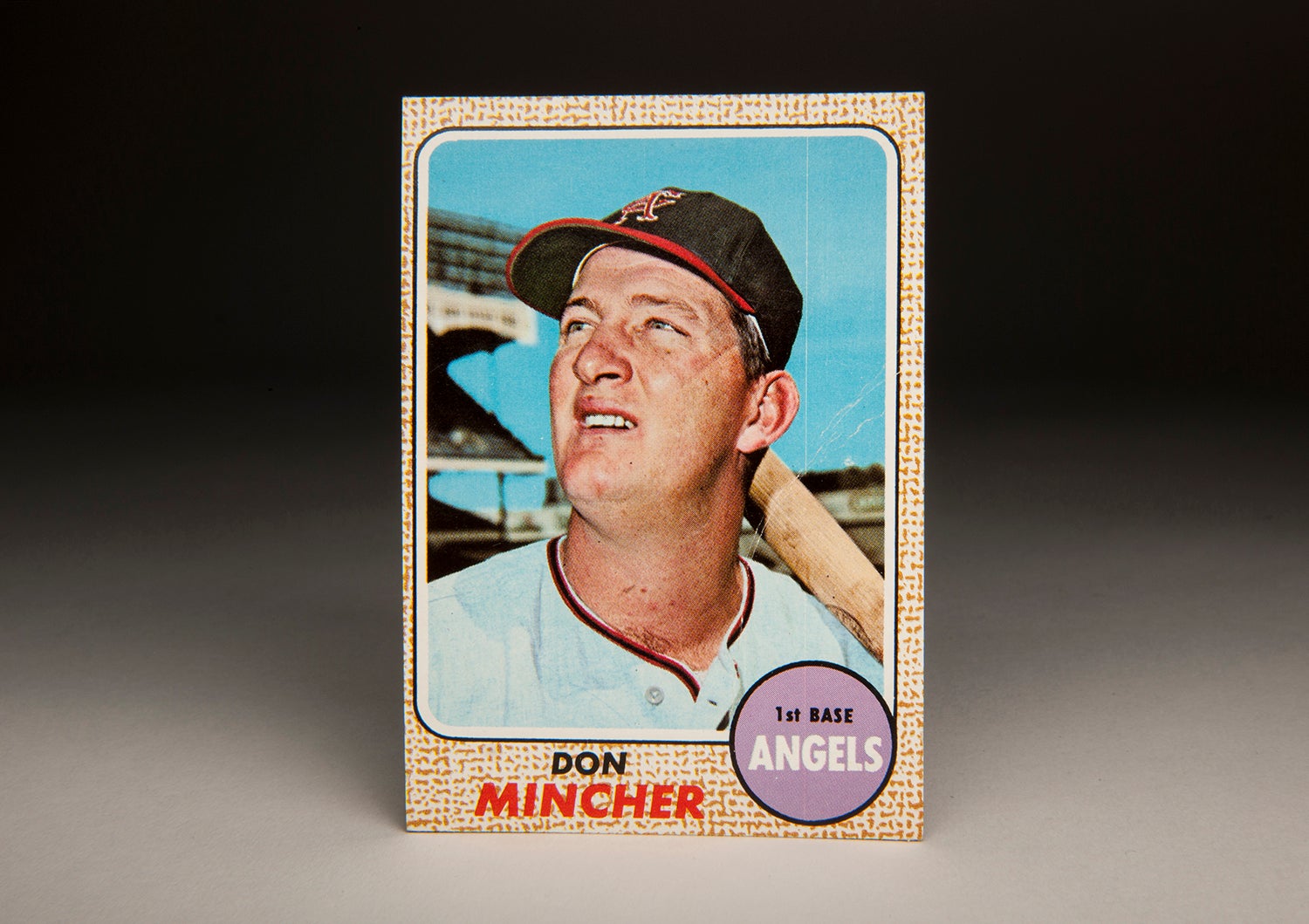

Platooning at first base, Goossen had his way with a number of the American League’s left-handed pitchers. He especially enjoyed playing at Sick’s Stadium, the aging and decrepit ballpark of the Pilots; all 10 of Goossen’s home runs came at Sick’s Stadium. It’s worth wondering what Goossen might have done if the Pilots had made him an everyday player, but the presence of the lefty-swinging Don Mincher made that an impossibility.

Though Goossen played only two full months for the Pilots in 1969, he did emerge as one of the lasting characters in Jim Bouton’s bestselling book, "Ball Four". In the early pages, Bouton recalled playing in a minor league game against Goossen a few years earlier. One of Bouton’s teammates bunted a ball back toward the pitcher. Springing from behind home plate, Goossen yelled repeatedly, “First base, first base, first base!” Ignoring his catcher, the unnamed pitcher threw the ball to second base, too late to nab the lead runner.

As a disgusted Goossen returned to his position, Bouton yelled from the dugout, “Goose, he had to consider the source!” Goossen’s disgust with his pitcher soon turned to laughter at Bouton’s sarcastic but good-natured remark.

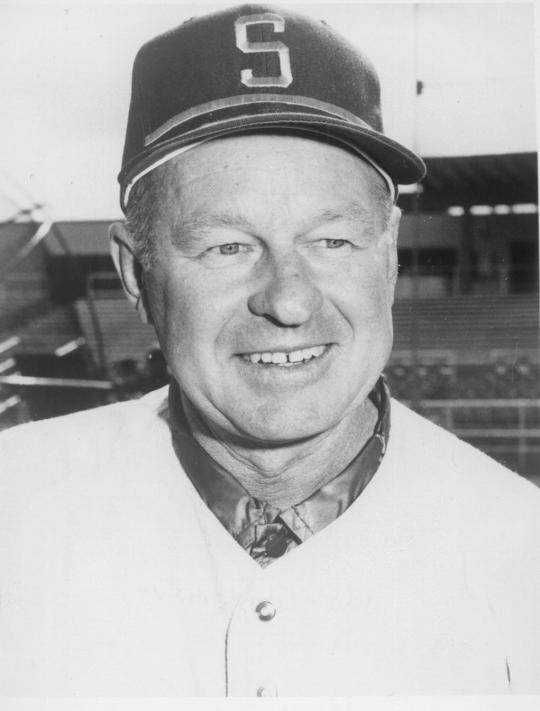

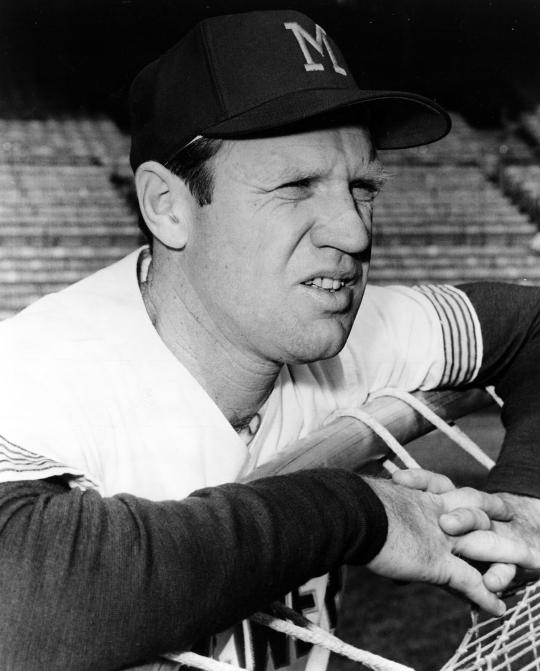

Now teammates with the Pilots, Goossen and Bouton quickly became friends. Goossen enjoyed his season in Seattle and also took a liking to his manager, the colorful Joe Schultz. But that situation would soon fall by the wayside. After the season, the Pilots fired Schultz, a move that upset many of the players in Seattle. The Pilots replaced Schultz with Dave Bristol, a manager with a harder edge. To make matters even more complicated, the owners of the Pilots’ franchise would sell to Bud Selig only five days before the start of the 1970 season; he would then relocate the team to Milwaukee. As a result, the newly minted Brewers began the season under frenetic circumstances.

Initially, Bristol made Goossen his starting first baseman, but the slugger did not find Milwaukee’s County Stadium as inviting as Sick’s Stadium. He slumped so badly at the outset of the season that the Brewers demoted him to Triple-A. Goossen would never again play for the Brewers. Later that summer, the organization sold his contract to the Washington Senators. (For those keeping score, this now marked the third expansion team that Goossen had joined, after the Mets and Pilots.) The move to Washington gave Goossen a chance to play for Ted Williams, one of the game’s leading hitting gurus, but he continued to struggle in Washington as he had in Milwaukee.

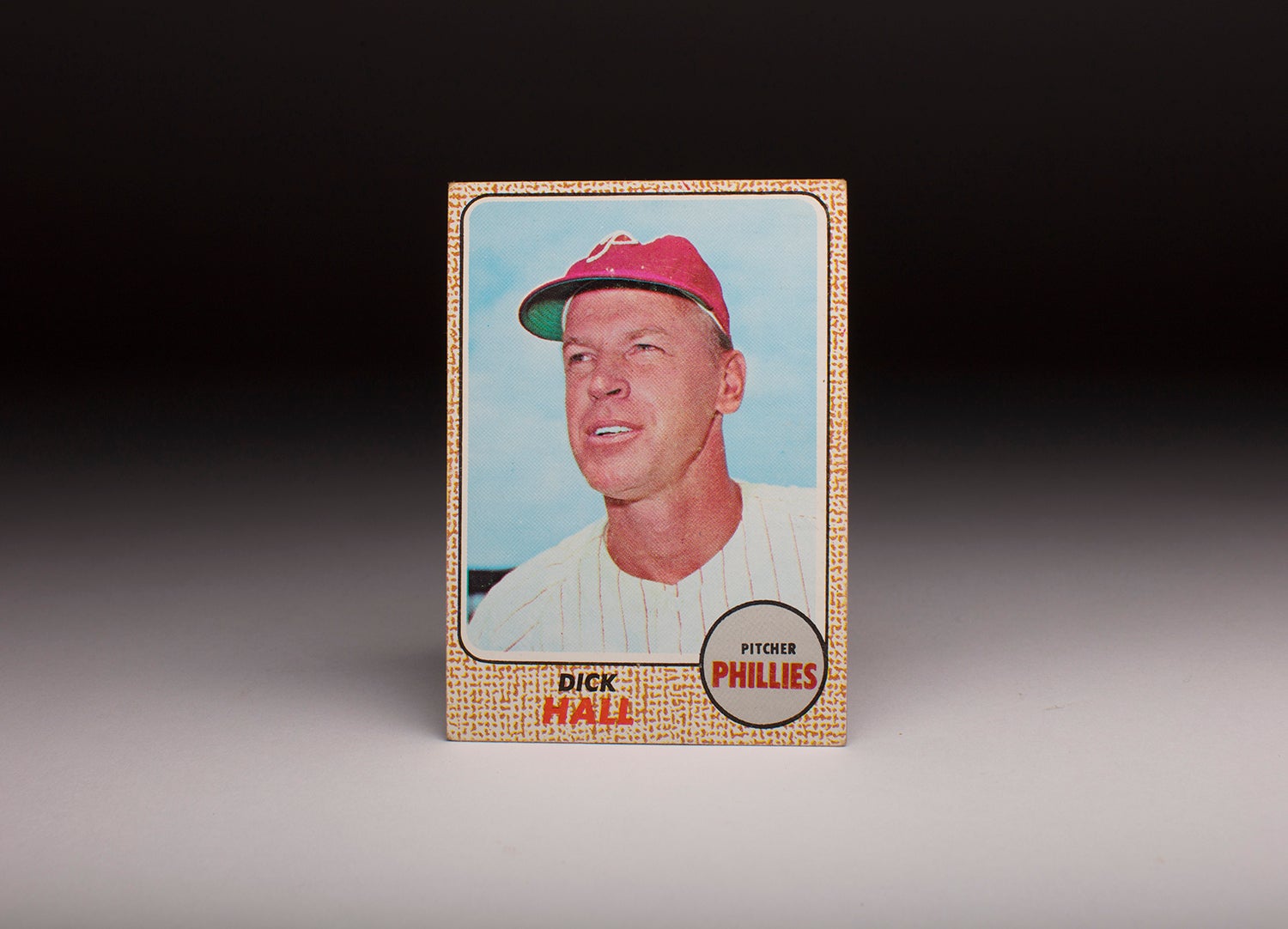

After only a half-season, the Senators gave up on Goossen. At the end of the 1970 season, they traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies as part of the ill-fated Curt Flood blockbuster. Goossen continued to search for his power stroke, but the Senators sent him packing after a half-season, sending him to the Phillies as part of the deal for the exiled Curt Flood. Goossen spent a strange 1971 season as a minor league vagabond, splitting time with the Triple-A affiliates of three organizations: The Phillies, Chicago Cubs and California Angels. Trapped in the limbo of minor league ball, Goossen would never make it back to the big leagues.

While Goossen’s playing days were over, he was still only 25 and ready to pursue his next career. He put in increased hours at his father’s private eye agency, a job that he had first dabbled in during the winters of his baseball career. But Goossen preferred spending most of his time working for a boxing gym called Ten Goose Professional Boxing, which was being run by his brothers.

Goossen became a trainer of boxers, including a young middleweight named Michael Nunn, who would become a champion in the 1980s. It was while working at the gym than Goossen first met Hackman, setting him on yet another career course. With success in several areas, Goossen compiled one of the most diverse careers of any retired ballplayer.

As a reward for his varied career accomplishments, his alma mater, Notre Dame High School in Sherman Oaks, Calif., named him to its inaugural Hall of Fame in 2011. The school invited him to the induction ceremony, scheduled for February 26. In anticipation of the ceremony, the school asked Goossen to come out early for a series of photographs. His daughter Erin waited for him at the school, but a full 45 minutes came and went, with Goossen nowhere to be seen. Concerned about his welfare, Erin left the school and hurried to his home in Sherman Oaks. Sadly, that is where she found him, unresponsive. Goossen had suffered a fatal heart attack. He was 65.

Like many retired ballplayers, Goossen died too young. But he packed a large amount of living into his 65 years. Even if you don’t remember him as a player, his name should come to mind the next time a Gene Hackman film comes on TV. If you’re watching one of Hackman’s better offerings, you might just get a glimpse of the guy who was once 19 and did a lot more than just turn 29.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame