- Home

- Our Stories

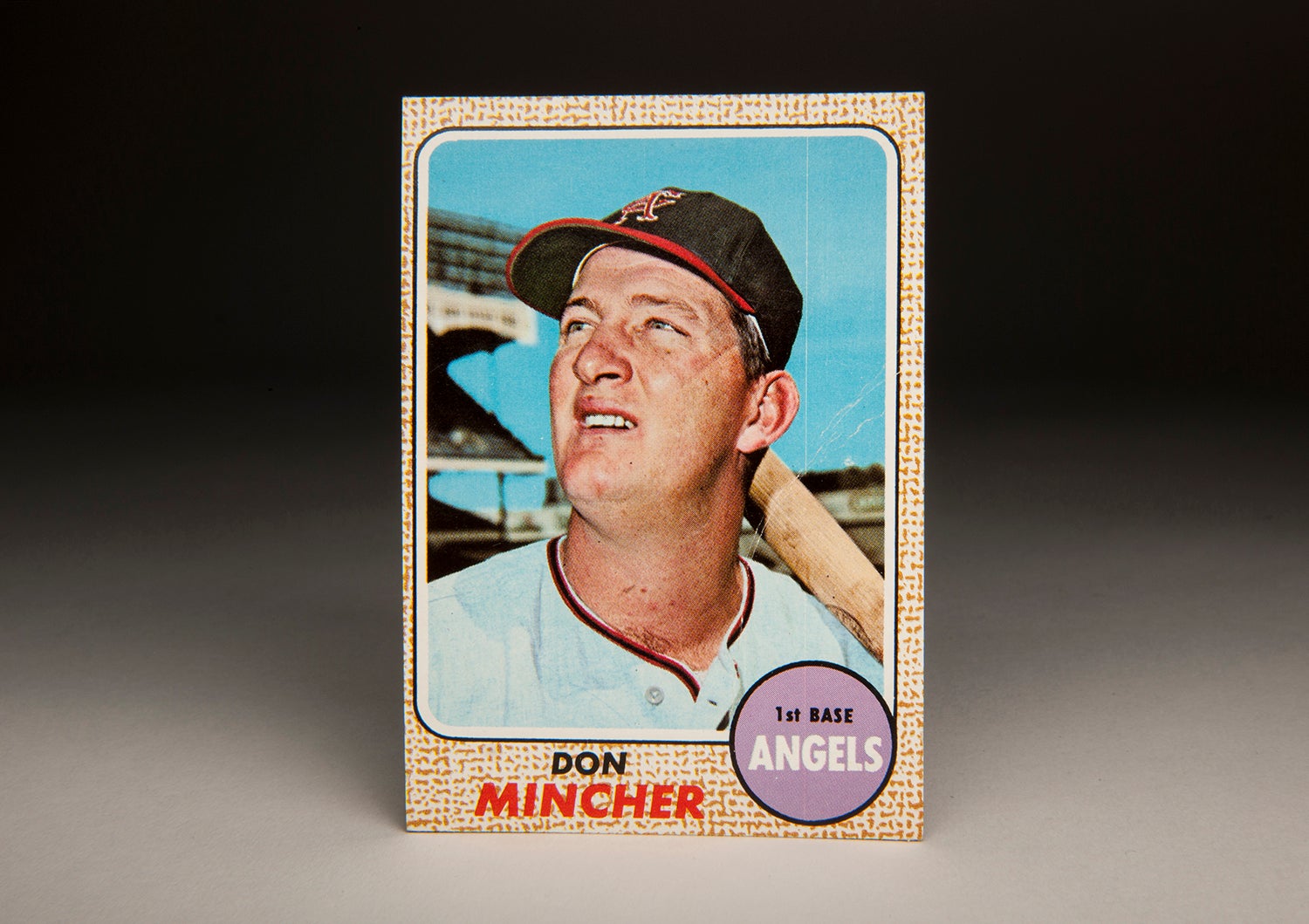

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Johnny Callison

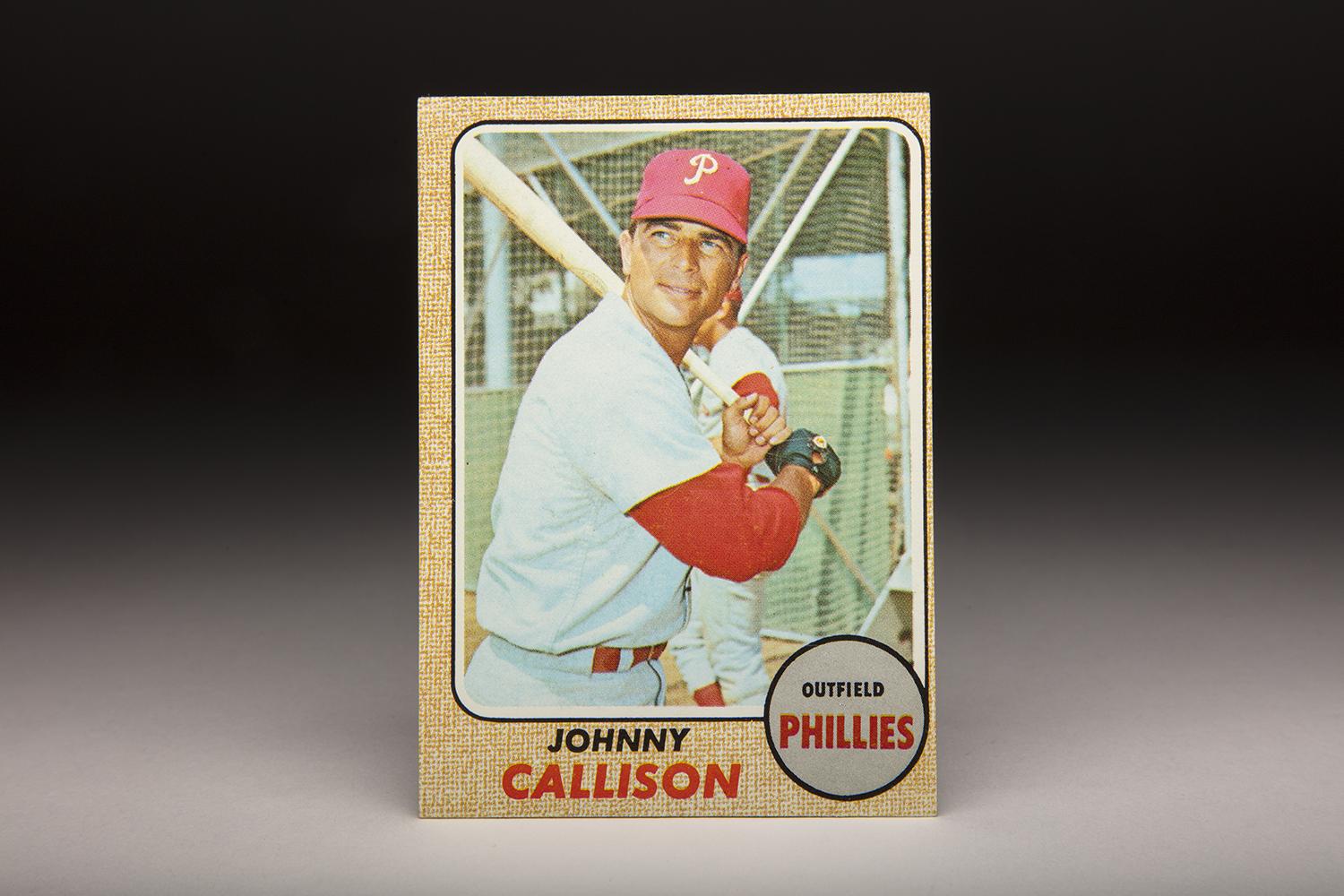

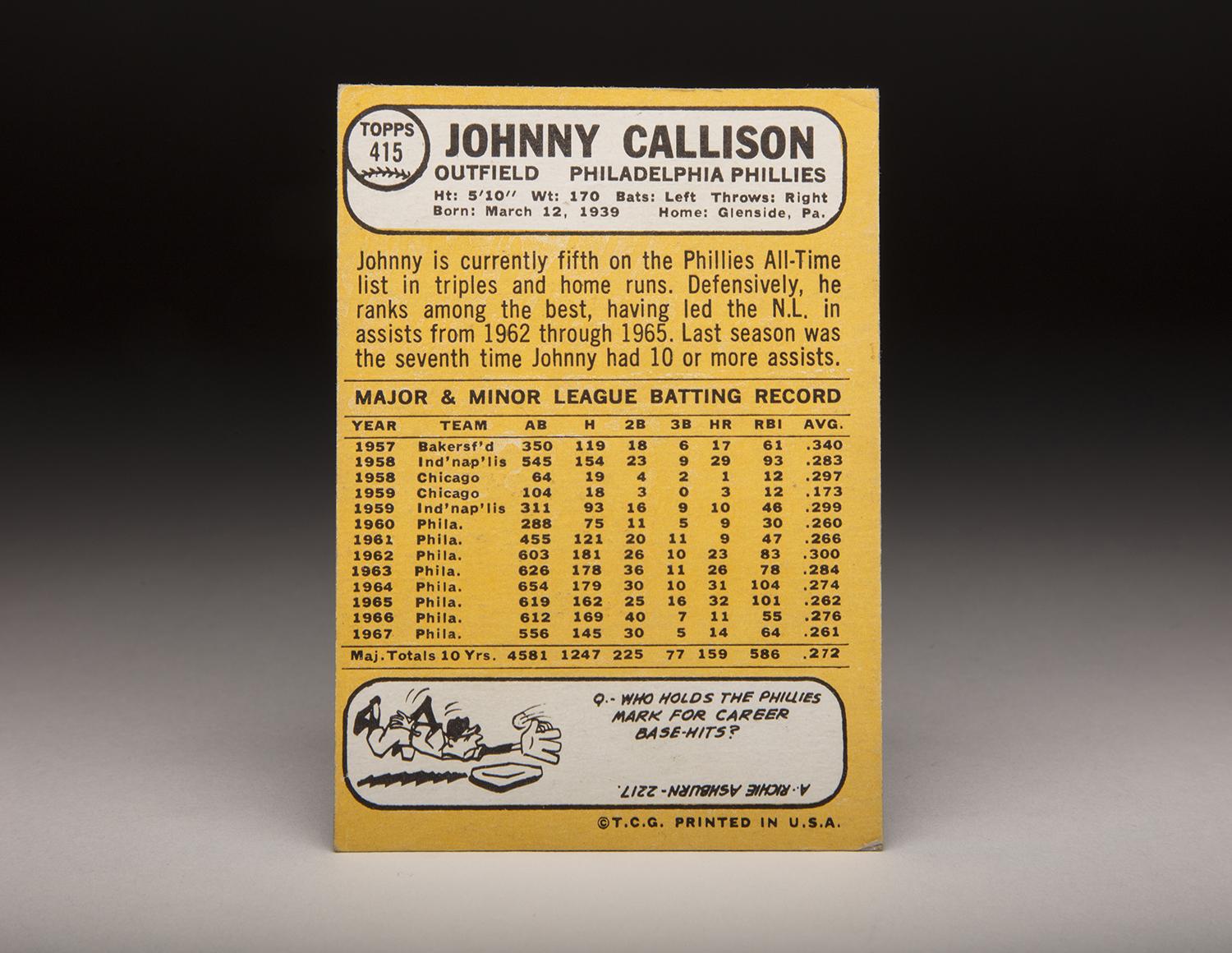

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Johnny Callison

My goodness, what is Colonel Flagg doing wearing a Philadelphia Phillies uniform on this 1968 Topps card?

For those who have no idea what I’m referring to, “Colonel Flagg” was a CIA operative and recurring character on the 1970s hit series, M*A*S*H. Not only was Flagg a memorable character, but he also bore an uncanny resemblance to former Phillies star Johnny Callison, one of the best all-around outfielders of the 1960s.

In examining this card, along with several other cards portraying Callison during the 1960s, I nearly did a double take in seeing the similarity of the facial features between Callison and the man who played Colonel Flagg. The not-so-good Colonel was played brilliantly by the late character actor, Edward Winter, who specialized in making guest appearances on television shows in the 1970s and 80s, in everything from Murder She Wrote to The Love Boat. Winter and Callison could have been brothers, if not identical twins.

Other than good looks and strong physiques, Callison and Flagg did share at least one other characteristic. Both sustained their fair share of injuries. In Flagg’s case, the injuries were almost always self-inflicted. In one of his earliest appearances on M*A*S*H, the Colonel intentionally injured himself by breaking a rotary telephone onto his head and then ramming himself headfirst into a wooden locker, causing a severe concussion. In another episode, Flagg decided to break his arm by pinning it under a heavy piece of X-Ray machinery.

As the show’s main protagonist, Captain Hawkeye Pierce, said in assessing one of Flagg’s self-inflicted wounds, “If we had more men like you, we’d have less men like you.” More accurate words have never been said.

In perhaps his most memorable appearance on M*A*S*H, Flagg wrapped up a meeting in Colonel Potter’s office by asking members of the 4077 to cover their eyes so that he could make his trademark “secret” exit. Claiming that he never allowed anyone to see him leave the scene of one of his investigations and proclaiming himself “The Wind,” Flagg promptly leapt through the office window. He made it outside – but not before hurting himself again. Hawkeye took a look outside the window and summarized the situation. “The Wind just broke his leg.”

Unlike Flagg, Callison’s injuries were not based on an idiotic desire to harm himself. It should also be pointed out that Callison was far more competent at playing baseball than Flagg was in performing duties as a daffy and paranoid CIA operative during the Korean War. Callison’s career accomplishments are especially impressive in light of his upbringing.

The son of migrant workers, Callison lived in poverty in Oklahoma before his family moved to California. Their first home in Bakersfield was nothing more than a shack; the lack of money became a source of embarrassment for Callison, who felt as if others looked down on him and his family because of their financial status.

As a youngster, Callison struggled in school but took a liking to baseball. In high school, his coach, a man named Les Carpenter, took him under his wing, often inviting him to the house for lunch and dinner. Aided and encouraged by Carpenter, Callison became such a fine amateur player that he drew interest from the Chicago White Sox organization. In 1957, long before the adoption of the major league draft, the Sox signed him and assigned his contrast to Bakersfield of the California League. Playing at the Class C level, Callison showed little trouble in adjusting to life in the professional ranks, batting .340 with 17 home runs in 86 games.

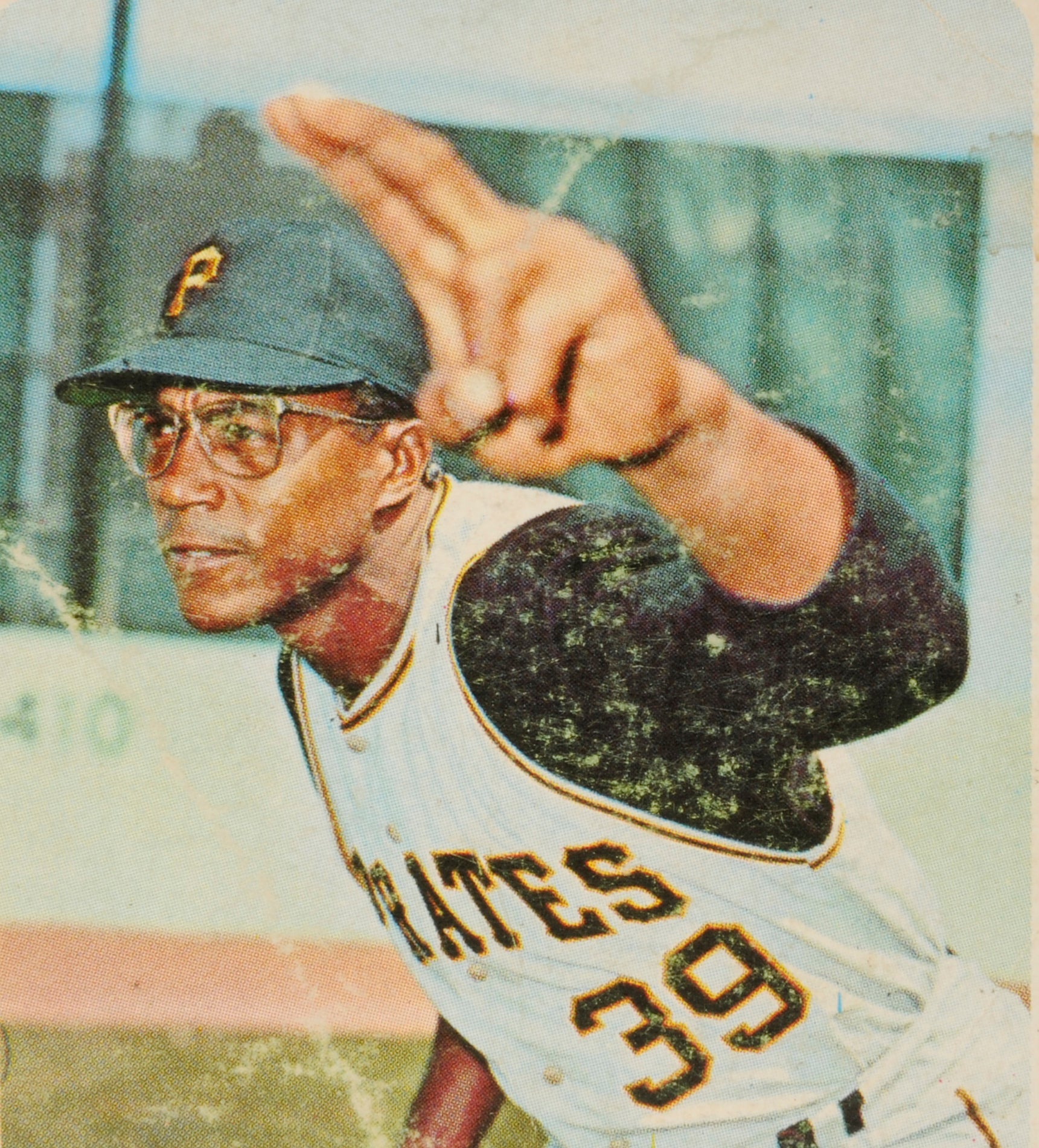

Callison hit so well in his pro debut that the White Sox advanced him all the way to Triple-A Indianapolis in 1958. Although he was still only 19, Callison continued his abuse of opposing pitchers, hitting at a .286 clip with 29 home runs and 76 walks. It was during that season that writers began to compare Callison to Mickey Mantle, who also hailed from Oklahoma. While Callison could do it all – hit, run, throw, and hit with power – it was an unfair comparison, just as it was for other players regarded as the second coming of Mantle, like Bobby Murcer.

After a full season at Triple-A, the White Sox gave Callison a late looksee in September. He came to bat 64 times and more than held his own, batting .297 with a .352 on-base percentage. He appeared to be on the verge of establishing himself as a fulltime major leaguer.

Callison’s successful debut helped him earn a spot on Chicago’s Opening Day roster in 1959. Given an extended stay in the big leagues, Callison struggled, his batting average sinking below .200. By June, the White Sox felt it was better for him to return to Triple-A Indianapolis, where he would remain until September.

The White Sox needed help in right field, the logical position for Callison to play given his strong throwing arm. But some within the organization considered Callison an underachiever. That December, the Sox decided to trade youth for experience, sending Callison to the Phillies for veteran infielder Gene Freese, coming off a season in which he had hit 23 home runs. While Freese was an established player, it would turn out to be an ill-advised and short-sighted trade that the White Sox would regret for the better part of the next decade.

The move to Philadelphia turned out to be a godsend for Callison. A rebuilding team, the Phillies could afford to be patient with their young slugger. Manager Gene Mauch, who loved Callison’s five-tool talent, worked him into the lineup gradually, using him as a left fielder and bench player. Still raw and unrefined, Callison endured a series of fits and starts in 1960 and ’61, as Mauch worked with him on improving his game. Principally, Mauch taught Callison how to bunt and preached to him the importance of using the entire field, rather than trying to pull the ball exclusively.

Thanks in part to Mauch, Callison blossomed in 1962. That year, Callison became the Phillies’ fulltime right fielder, hit an even .300, belted 23 home runs, and led the National League with 10 triples. On the basis of a strong first half, he made the All-Star team and continued to contribute during the second half, earning some consideration for league MVP.

In 1963, Callison’s batting average fell off by 16 points, but he retained his power stroke, his strong defensive play and his cannon-like throwing arm. Then came the breakthrough of 1964. Earning his second All-Star Game nod, Callison ended the Midsummer Classic by hitting a three-run homer against flame throwing right-hander Dick Radatz. It became one of the most memorable moments in All-Star Game history.

Led by Callison and rookie Dick Allen, the Phillies seemed primed to win the National League pennant. But a late 10-game losing streak doomed the Phillies. In contrast to many of the slumping Phillies, Callison played well during that final stretch, hitting four home runs. When critics pointed the finger at Mauch, Callison became one of his manager’s few public defenders. He absolved Mauch of much of the blame, saying that the players needed to accept culpability for the late-season collapse.

With 31 home runs and an .809 OPS, Callison finished second in the National League MVP voting. Many historians believed that if the Phillies had held on to their lead, Callison would have taken home MVP honors. Even with a second-place finish in the MVP race, Callison cemented his status as the most popular Phillie with the team’s fan base. In particular, his power and his throwing arm made him a fun player to watch.

Callison played even better in 1965 than he did in ’64. He hit 32 home runs, slugged over .500, increased his walk total, and again made the All-Star team. But with the Phillies settling in as a sixth-place team, the writers mostly ignored Callison in the MVP voting. He finished 24th in the balloting, despite his improved offensive numbers.

During the spring of 1966, Callison turned 27 years old, seemingly in the middle of his prime. It was at this point that nagging leg injuries began to take their toll. Callison also complained of problems with his vision. For a while, he wore glasses, but that didn’t help his hitting, which fell off precipitously in ’66. Mauch also criticized him for a lack of hustle, a charge that Callison refuted.

Additionally, Callison had a tendency to worry. In fact, he had admitted as much during an interview with Sport Magazine in 1964, when he proclaimed himself “the biggest worrier around.” Some observers felt that Callison fretted so much that it affected his confidence.

The combination of worry and the breakdown of his body, which may have been exacerbated by a heavy smoking habit, led to an early decline for Callison. From 1966 to 1969, he became a second-tier player; he missed more and more games with injury, and his power fell off. For the rest of his career, he failed to reach the 20-home run plateau and never again raised his OPS above .800.

Callison also happened to turn 30 during the 1969 season. Realizing that Callison was unlikely to discover his previous glory, the Phillies traded him that winter, sending him to the Chicago Cubs for a young Oscar Gamble and righty reliever Dick Selma. Cubs manager Leo Durocher expressed delight with the addition of the veteran outfielder. “After Roberto Clemente,” Leo told the Chicago media, “Callison has the best arm in the league so far as I am concerned.”

Over the first half of his debut season with the Cubs, Callison played well. He showed increased patience at the plate and made better contact, while generally taking well to Wrigley Field. But suddenly in July, Durocher began to platoon Callison. At times, Durocher took his veteran outfielder out of games for a pinch-hitter, something that rarely happened in Philadelphia.

Callison finished the 1970 season with a .264 batting average and 19 home runs, but he felt the numbers would have been much better if not for the platooning. The situation only worsened in 1971. A slumping Callison found himself on the bench more and more often, in part because of injuries to his ribs and groin. By season’s end, he played in only 103 games, his fewest since 1960.

Given his relationship with Durocher, Callison needed a change of scenery desperately. That came on Jan. 20, 1972, when the Cubs traded him to the New York Yankees for a player to be named later, which would turn out to be reliever Jack Aker. Eight years after his All-Star Game heroics, Callison was reduced to being traded for future considerations. To make matters worse, the deal was conditional, meaning the Yankees could return Callison to the Cubs by May 1.

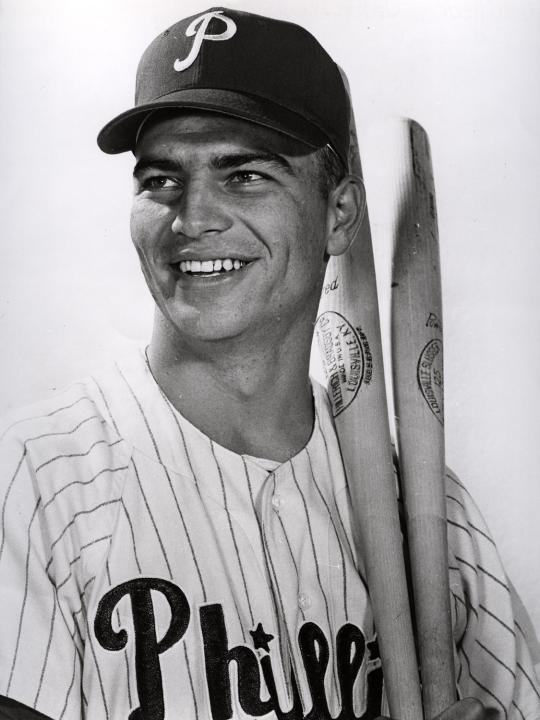

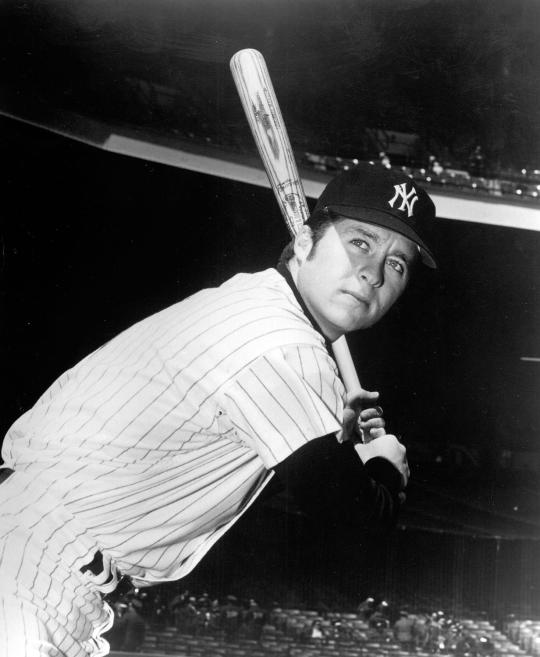

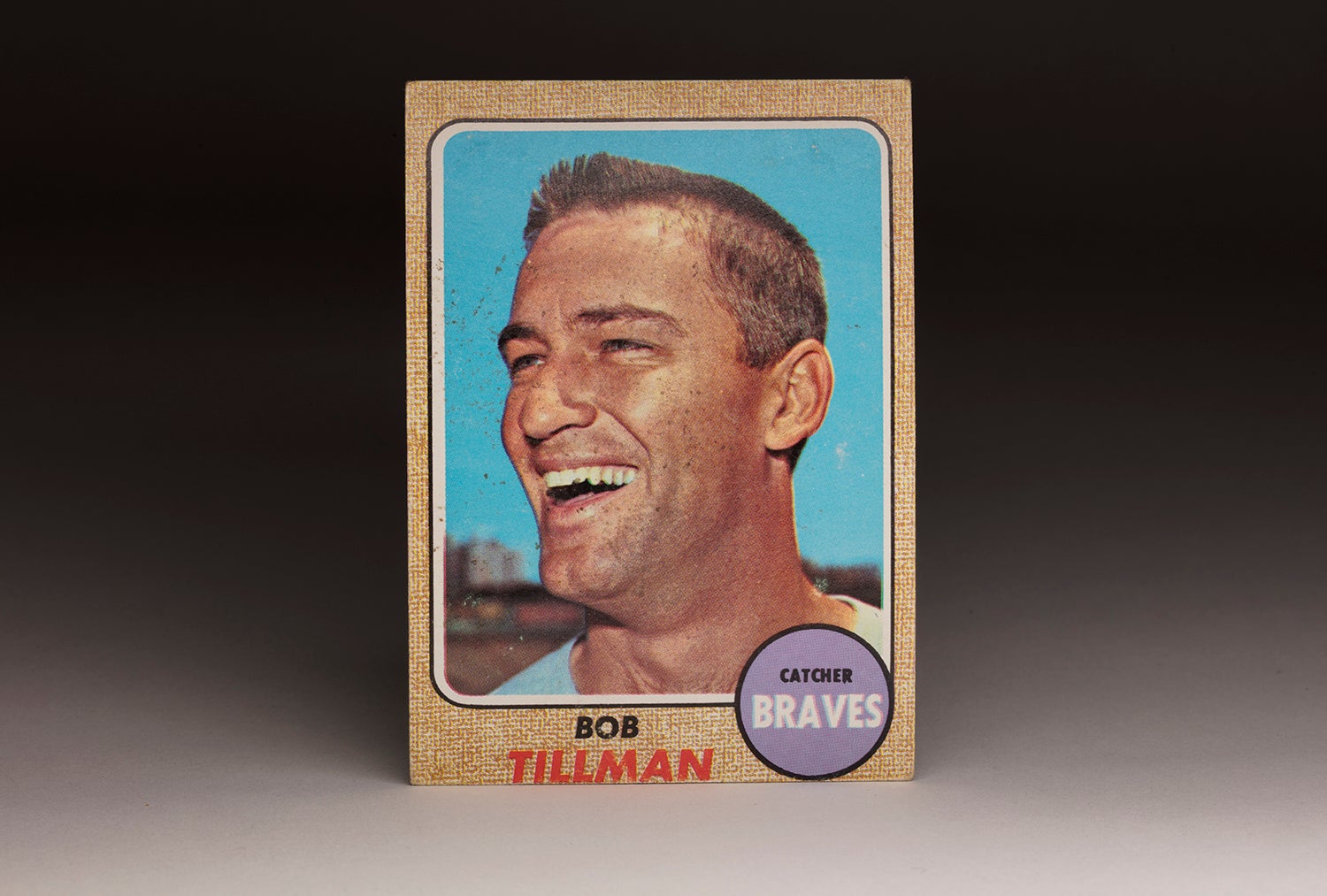

Johnny Callison spent the majority of his big league career with the Philadelphia Phillies, occupying the right field spot from 1960-1969. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

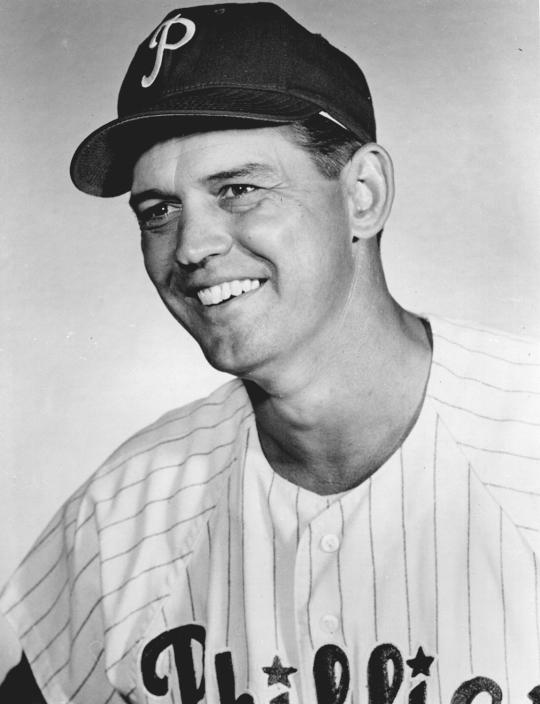

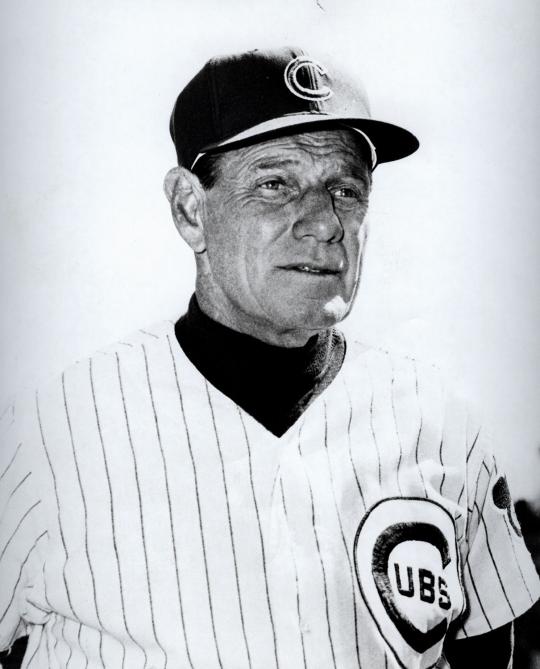

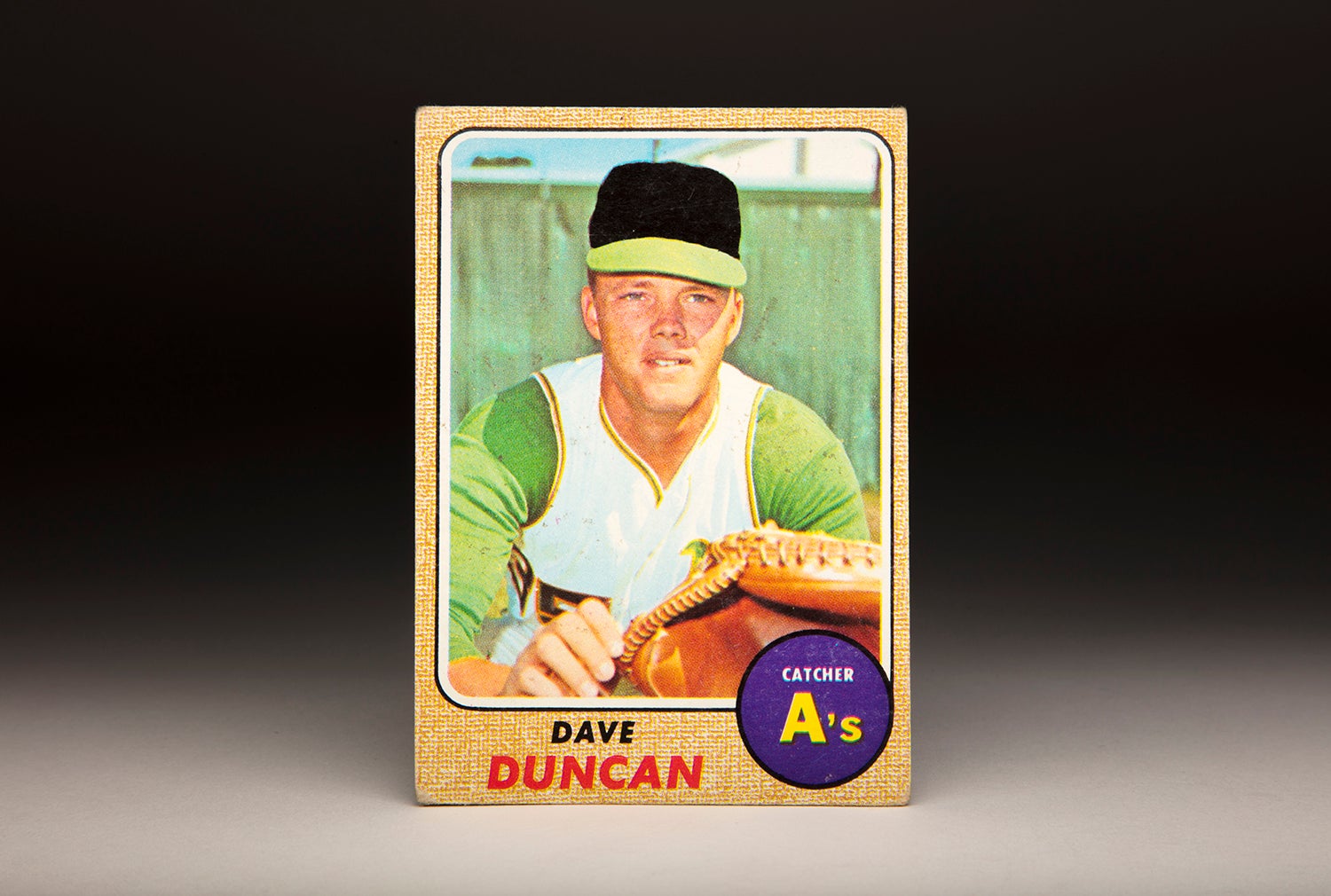

Phillies manager Gene Mauch admired Johnny Callison's five-tool talent, and worked him into the lineup gradually after Callison was traded to the Phillies in 1959. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Similarly to Johnny Callison, Oklahoma native Bobby Murcer (pictured above) evoked comparisons to Yankees legend Mickey Mantle. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Initially, the Yankees viewed Callison as a left-handed pinch-hitter but he would become their platoon right fielder, switching on and off with ex-Met Ron Swoboda. Staying with the Yankees for the entire season, Callison hit better for them than he did for the Cubs in 1971, but he also failed to reach double figures in home runs. He would play one more season for the Yankees – dismal summer in 1973 – before drawing his release in August.

After his playing days, Callison made a series of investments that failed badly, leaving him with little money. Forced to work a number of jobs, including stints as a bartender and a car salesman, Callison found little satisfaction in any of them, certainly nothing approaching the thrill of being a major league ballplayer. His only connection to the game would come through his participation in Phillies fantasy camps, where he became popular with fans, many of whom saw him play.

Callison’s health also suffered during his post-playing days. As a result of worry and stress, he struggled with ulcers and eventually suffered a heart attack. At one point, he had to have one of his legs amputated. In 1996, he struggled with an aortic aneurism that caused his belly to protrude as it a pillow had been placed inside of it. Callison underwent a five-hour surgery to remove the aneurism.

Later diagnosed with cancer, Callison died in 2006. He was only 67 years old. Upon news of his death, several of his Phillies teammates offered tributes, none more poignant than one coming from Dick Allen. “Johnny was more than a teammate to me, he was a close friend,” Allen told ESPN.com “He was a terrific player with a great arm from right field. He also had a funny, dry sense of humor.”

In light of his health problems, there’s always a tinge of sadness in recalling the story of Callison. He was also a player plagued by doubt and insecurity, which manifested itself in the constant worrying that became one of his unfortunate trademarks.

But then I’ll happen to watch another old episode of M*A*S*H, one featuring our old friend, Colonel Flagg. Sometimes when I see Flagg, I start thinking about Johnny Callison and what a fine, likeable ballplayer he was, and a smile comes over my face.

Colonel Flagg’s wacky character brought me lots of smiles, too. That’s what Flagg and Callison had in common, besides their looks. Of course, they were very different, too. Flagg made you smile because he was a little bit crazy, while Callison made you smile because he was just darn good.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum