- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Andy Etchebarren

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Andy Etchebarren

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

If you grew up with baseball in the 1960s and 70s, you remember Andy Etchebarren.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

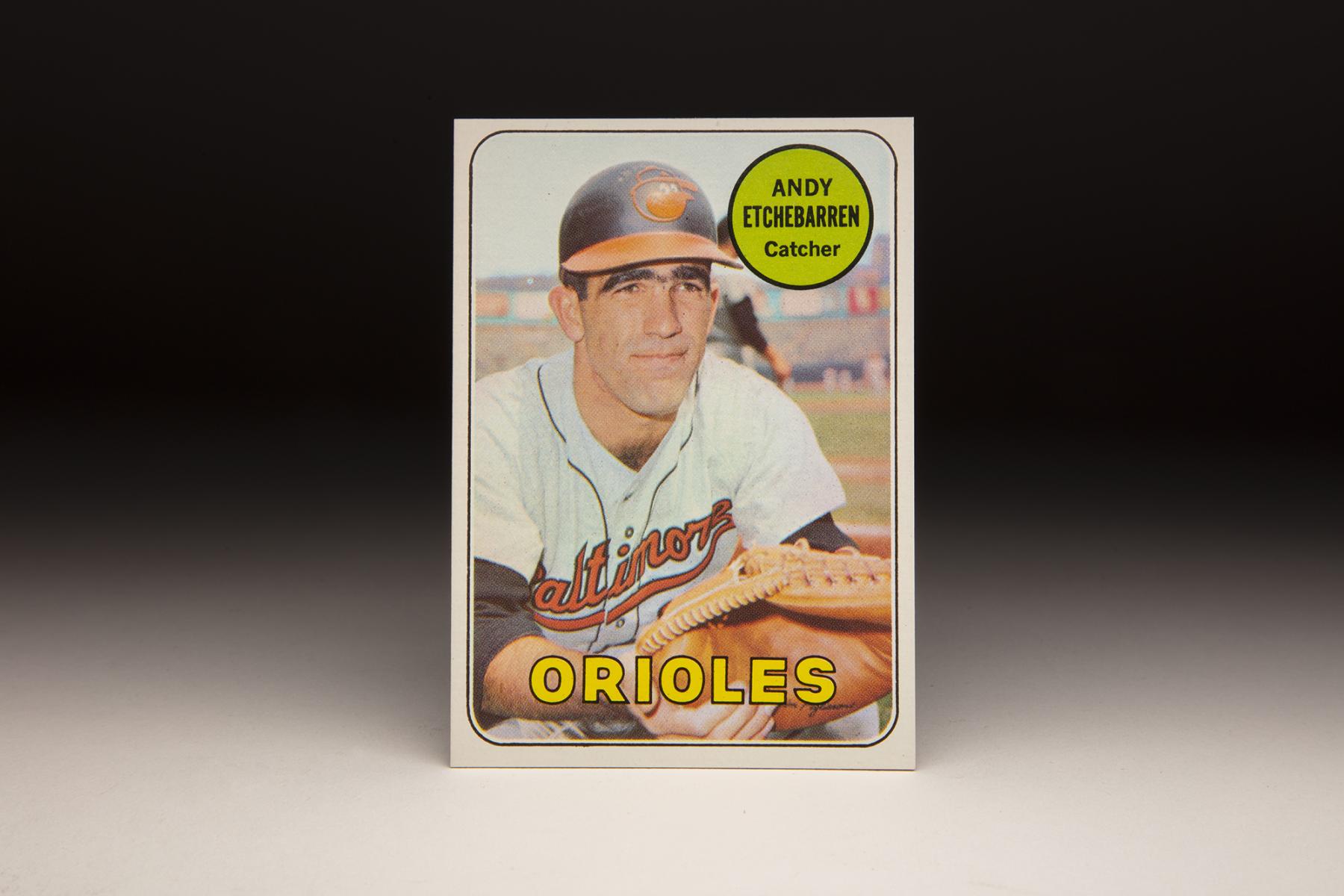

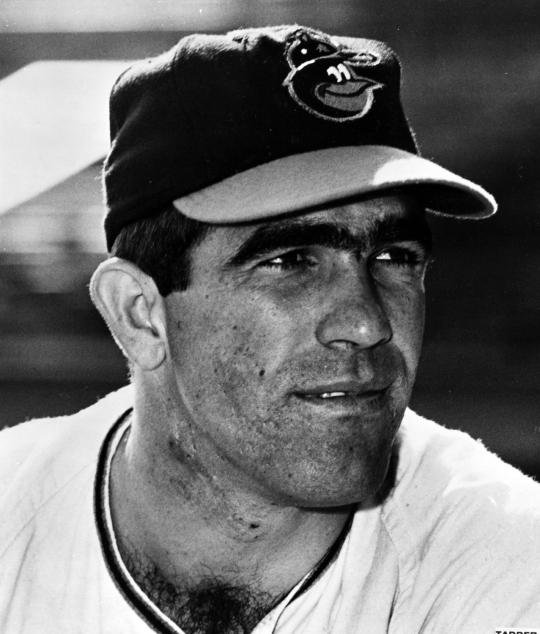

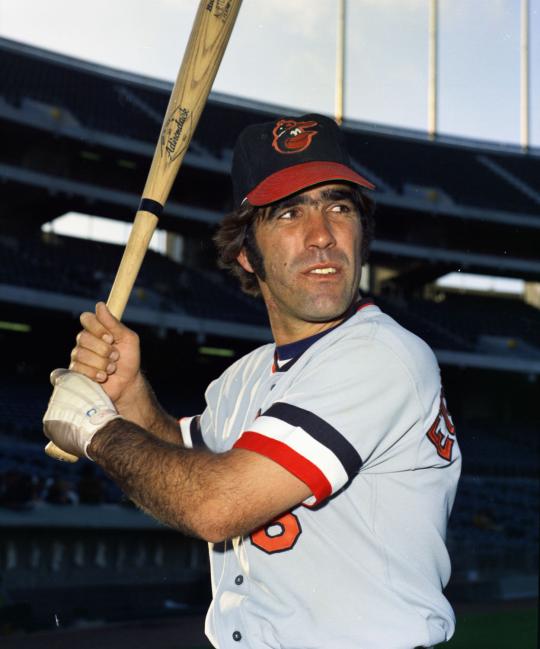

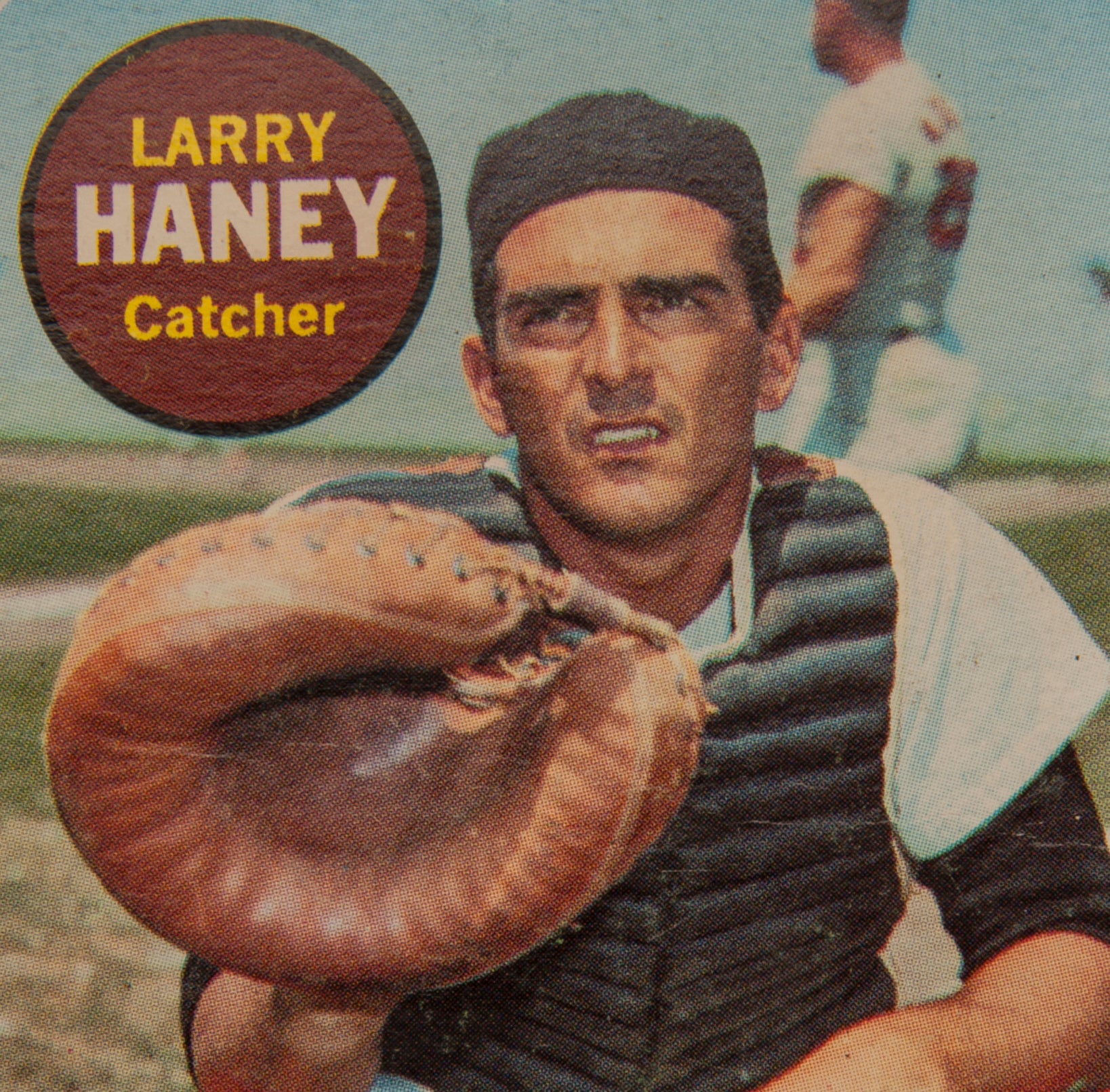

You had to – if only because of his distinctive look, which is quite apparent on his 1969 Topps card. With his dark, bushy eyebrows that usually connected in the middle, Etchebarren proved a worthy successor to Wally Moon as the owner of the game’s fiercest unibrow.

Etchebarren also had a long and thick chin, along with ruddy facial features that would have made him ideal as an extra on one of the Bowery Boys movies of the 1950s. Yes, there was no one in the game who looked quite like Andy Etchebarren.

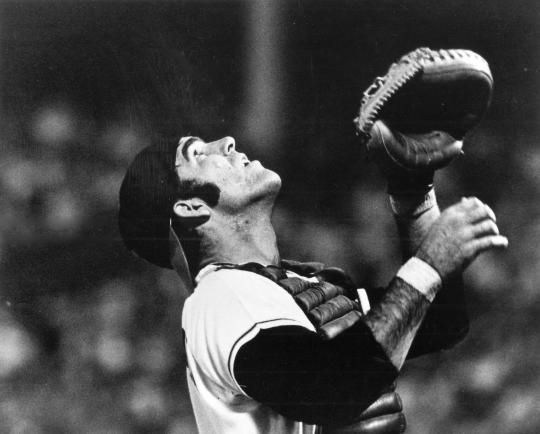

Photographed at what appears to be Yankee Stadium during the regular season, Etchebarren’s 1969 card shows him with an expression that is hard to categorize. It’s not a smile, but it’s not a frown either; it looks like he might be a little bored, which I suppose can happen during the hours that precede each game. But those moments of boredom apparently didn’t bother Etchebarren too much. After all, he spent 15 seasons in the major leagues as a player, and then 30 additional years as a coach and manager.

An important role player on two world championship teams with the Baltimore Orioles, Etchebarren died on Oct. 5, 2019. He was 76. Etchebarren was never a strong hitter, but his catching skills gave him a key place on winning teams in Baltimore. For a number of years, Etchebarren platooned at catcher with Elrod Hendricks.

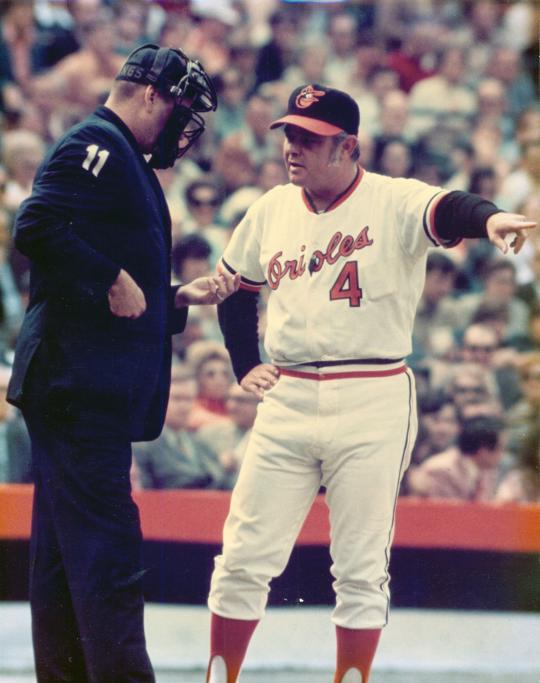

Orioles manager Earl Weaver loved to use platoons, and the Etchebarren/Hendricks combination became part of his trademark system in the late 1960sand early 1970s.

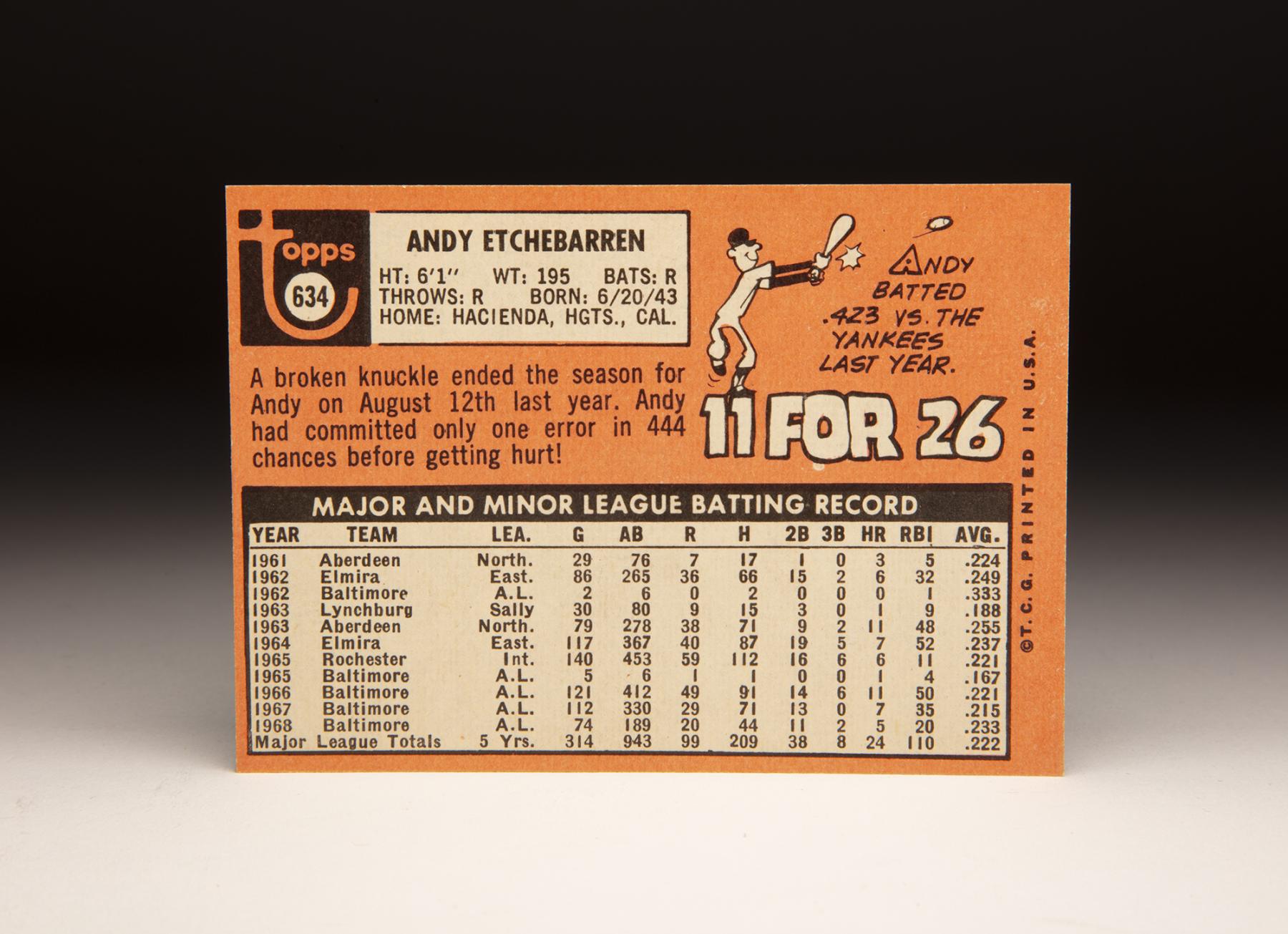

Etchebarren’s connection to the Orioles’ organization dates back to the 1961 season. That’s when Orioles farm director Harry Dalton brought the young catcher into the Baltimore organization. Dalton liked Etchebarren’s talent so much that he gave him a bonus of $85,000, a huge total for the time, and assigned him to Aberdeen of the Northern League. He didn’t hit much as a rookie, but showed strong defensive skills as a catcher. In 1962, the Orioles promoted Etchebarren to Elmira, where he batted a bit better, accumulating a .249 batting average and six home runs. Those numbers weren’t eye popping, but the Orioles felt that he was worth a late-season look in Baltimore. The O’s brought him up to play in two late-season games, and Etchebarren responded with a fine cameo, picking up two hits in six at-bats.

Etchebarren was still only 19 and not ready for fulltime major league duty, so it was back to the minor leagues in 1963. He split the season between Aberdeen, where he hit 11 home runs, and Lynchburg, a Double-A affiliate of the Chicago White Sox. On loan to the White Sox’ organization, Etchebarren found himself overmatched in Lynchburg, as evidenced by a .188 batting average in 30 games.

It was during his minor league apprenticeship that Etchebarren began receiving comparisons to Yogi Berra because of their similar facial features. Unfortunately, some of the comments about Etchebarren became cruel. A few fans referred to him as “Lurch,” after the unusual-looking butler in the popular comedy, The Addams Family. To his credit, Etchebarren sloughed off most of the remarks and remained committed to his path toward the major leagues.

In 1964, the Orioles allowed Etchebarren to play a full season at Double-A Elmira. He hit only .237, but showed a good eye by drawing 67 walks. It was on to Triple-A in 1965; playing for Rochester, his offensive game remained middling, but he continued to show an aptitude for catching. In September, the Orioles brought him up for six late-game appearances, mostly as a pinch-hitter.

Heading into the 1966 season, the Orioles expected Dick Brown to be their starting catcher. But Brown did not feel well during Spring Training and visited the hospital, where doctors determined that he had developed brain tumor. On March 7, surgeons removed the tumor, effectively keeping Brown out of action for the season. Additionally, Brown’s backup, Charlie Lau, suffered an elbow injury in the spring, sidelining him for the season. Now needing help at catcher, the Orioles turned to Etchebarren as their No. 1 catcher. That season, he appeared in 121 games. While he batted only .221, he played well enough during the first half of the season to make the American League All-Star team. For the season, he hit 11 homers and also prospered behind the plate. His teammates quickly grew to like his toughness and the way that he handled the Orioles’ talented pitching staff.

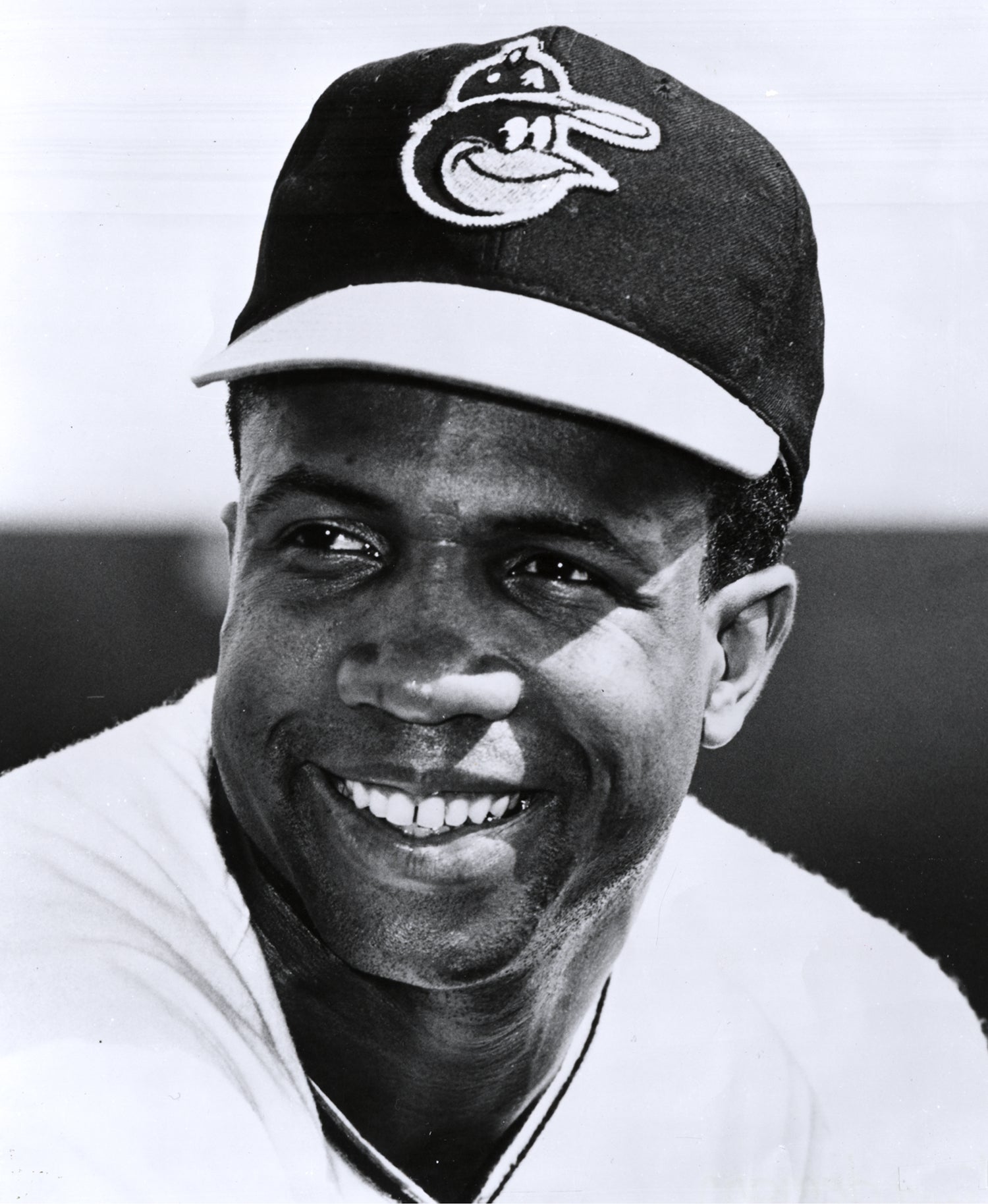

Etchebarren also contributed in a heroic way off the field. In August, the Orioles attended a swimming pool party in the nearby city of Towson. Some players decided to have some fun by pushing their teammates into the pool. Rather than allow himself to be pushed, Frank Robinson decided to jump into the pool.

To the surprise of his teammates, Robinson could not swim. Struggling to stay afloat in the deep end of the pool, Robinson began flailing his arms. Etchebarren, who was sitting poolside, noticed his teammate in distress.

“I saw Frank at the bottom in the deep end, waving his arms,” Etchebarren told the Baltimore Sun many years later.

“I thought he was messing around, but I dived in and went down to get him.” Etchebarren eventually reached his teammate, but the situation soon became more complicated. “He put such a strong grip on me I had to break free, come up for air, and go back down again to get him.”

Finally, Etchebarren pulled Robinson from the pool, saving the life of his teammate. Perhaps the writers took the incident into account when casting their votes for American League MVP. In actuality, Etchebarren carved out such an impact with his catching skills that the writers gave him some legitimate support in the balloting.

In the 1966 World Series, Etchebarren caught all four games against the Los Angeles Dodgers. He didn’t hit much, but continued to catch the Orioles pitchers with aplomb. The Orioles swept the Dodgers in four games, giving the franchise its first title since its move from St. Louis.

His contribution to a championship, along with his stellar defensive play, solidified his status as Baltimore’s starting catcher. Etchebarren again made the All-Star team in 1967, but his batting average sank to .215 and his home run production fell to only seven.

Several factors cut into Etchebarren’s playing time in 1968, a year in which he appeared in only 74 contests. He missed a number of games due to injury, while also losing some time to a young prospect, the left-handed hitting Hendricks. Then came a midseason change in managers.

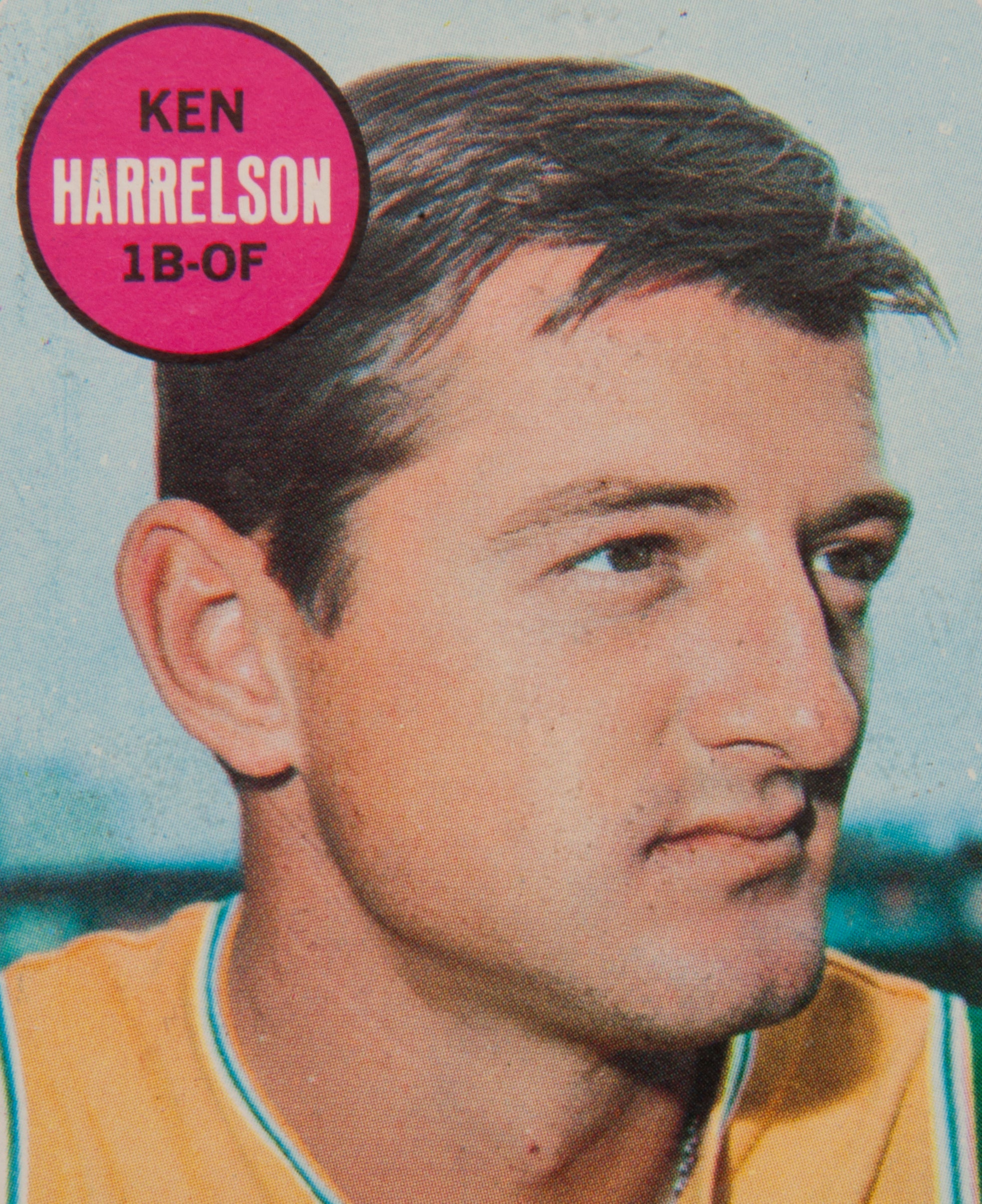

The Orioles fired Hank Bauer, a strong advocate of Etchebarren, and replaced him with Earl Weaver. While Weaver harbored no resentment toward Etchebarren, he liked Hendricks’ left-handed bat and saw an opportunity to platoon the two players.

Weaver continued the time-sharing arrangement in 1969. Although Etchebarren would have preferred playing every day, he understood the reasoning behind Weaver’s decision. Hendricks gave the Orioles a little more offense, while Etchebarren provided the superior defense. The tandem worked beautifully, playing a subtle role in the Orioles winning 109 games and taking the newly formed American League Eastern Division in a runaway.

The platoon arrangement continued in the playoffs and World Series. Etchebarren played two games in each round and came up hitless, but the larger disappointment occurred when the Orioles lost the World Series in five games to the youthful and seemingly overmatched New York Mets.

The 1970 season would yield better results. After playing in 78 games during the regular season, Etchebarren picked up his first two hits in postseason play, one in the ALCS against Minnesota and one in the World Series against Cincinnati. The Orioles dominated the Reds, winning the Series in five games and giving Etchebarren his second World Series ring in five seasons.

In 1971, Etchebarren again played in the range of 70-plus games, but put up career-best numbers at the plate. He batted .270, hit nine home runs and posted an OPS of .749 – the latter being the best of his career.

The World Series once again resulted in disappointment, however; Etchebarren came up hitless in one game, spent the rest of the Series on the bench and saw his heavily favored Orioles team lose the title to the Pirates despite dominating the first two games in Baltimore.

The 1972 season would prove to be one of the most frustrating of Etchebarren’s life. Hendricks went down early in the season with a calcium deposit in his neck, giving Etchebarren a chance to play every day. But he didn’t hit, prompting Weaver to use young Johnny Oates as his left-handed hitting catcher. Etchebarren never got untracked offensively; he batted only .202 for an Orioles team that failed in its bid to win a fourth consecutive AL East title.

That winter, the Orioles hoped to bolster their offensive production by acquiring slugging catcher Earl Williams from the Atlanta Braves. The move placed Etchebarren third on the depth chart, behind Williams and Hendricks. For most of the season, Etch rode the bench, but Williams’ problems behind the plate convinced Weaver to turn to his old standby late in the season. Etchebarren played well down the stretch, helping the Orioles to win another division title. He remained the starting catcher in the ALCS, batting .357, including a three-run homer, against the Oakland A’s.

As much as Etchebarren hit in the postseason, he couldn’t prevent the Orioles from losing the fifth and final game of the series, as the Orioles’ season came to an end.

It seemed that Etchebarren’s career with the Orioles might also be ending following the 1974 season, where he played in 62 games and the Orioles again lost to the A’s in the ALCS. Unhappy with his status as a backup catcher, Etchebarren decided to hold out at the beginning of Spring Training in 1975. He told the Orioles’ new general manager, Frank Cashen, to either work out a trade with the California Angels, allowing him to be closer to his wife and children, or give him a new three-year contract. The Orioles refused on both counts.

After two weeks of sitting at home, Etchebarren couldn’t take the inactivity anymore and reported to Orioles camp. He played well in the spring, surprisingly earning the No. 1 catching job ahead of Dave Duncan, who had been acquired as a replacement for the traded Earl Williams. But then came more adversity. During the very first week of the season, Etchebarren strained his Achilles tendon and then suffered a fracture to his elbow. The injuries sidelined him for the next week.

Etchebarren felt that he could return sooner, but the Orioles disagreed. So the veteran catcher filed a grievance with the Players Association, claiming that he was being kept on the disabled list against his will. Finally, Etchebarren was reactivated by the Orioles, but he remained unhappy and again requested that the team trade him, preferably to California.

On June 15, the Orioles gave Etchebarren what he wanted, selling him to the Angels. The deal not only allowed Etch to be closer to his family – Anaheim Stadium was only a 20-minute drive from his home – but it also created a reunion with Harry Dalton, the former Orioles exectutive who was now running baseball operations for the Angels.

The Angels immediately announced that Etchebarren would become their starting catcher. And then, only two weeks later, he suffered yet another injury, this time a broken thumb. He would miss all of July and most of August before finally returning to action. By the end of the season, he appeared in only 31 games for California.

Even though Etchebarren was now 31 and increasingly injury prone, the Angels remained committed to him in 1976. He appeared in 103 games and provided some leadership to a young pitching staff, but did not hit well, compiling an OPS of .577. In 1977, the Angels brought him back as a player/coach, but no longer as the starting catcher. After the season, the Angels sold their veteran receiver to the Milwaukee Brewers, where Harry Dalton was now serving as GM. Etchebarren appeared in only four games for the Brewers during an injury-riddled season. At the end of the 1978 campaign, Etchebarren retired.

Initially, Etchebarren chose to leave baseball completely, instead buying and operating a racquetball club near his home. But after three years in that new line of work, Etchebarren hoped for a return to baseball. He approached Dalton, who offered him a job as the Brewers’ roving minor league catching instructor. Etch then became a minor league manager before earning a spot on the major league coaching staff, working under Tom Trebelhorn in 1986 and ‘87.

In the early 1990s, Etchebarren reunited with his original organization, the Orioles. He worked as both a minor league manager and major league coach, before leaving the O’s at the end of the 2007 season. He then turned to managing independent minor league ball, where he won two Atlantic League titles, before finally retiring in 2012. As a manager of a team called the York Revolution, Etchebarren developed a reputation for being tough and favoring an old-school approach. His arguments with umpires who had delivered questionable calls became the stuff of legend in the Atlantic League. Yet, his gruff exterior masked a tendency toward being a players’ manager, one who was well-liked by those who suited up for him.

Upon learning of Etchebarren’s death, York president Eric Mencher praised his former manager.

“Etch was York Revolution baseball for many years. He poured his love of the game into each season with us, gave us our first championships, and really paved the way for our success since,” Mencher told Fox 43 News of York, Pa. “I feel lucky to have known him, a tough guy with a heart of gold.”

On the outside, Etchebarren looked like he belonged in an Edward G. Robinson movie. On the inside, he had the kind of understated compassion that made him loved by his players. Either way, Andy Etchebarren epitomized what it means to be a baseball lifer.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum