- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Joe Grzenda

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Joe Grzenda

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

While his name might not be one that falls into the household variety, some of Joe Grzenda’s images on Topps cards are quite memorable – and perhaps best epitomized by his appearance in the 1969 Topps set.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

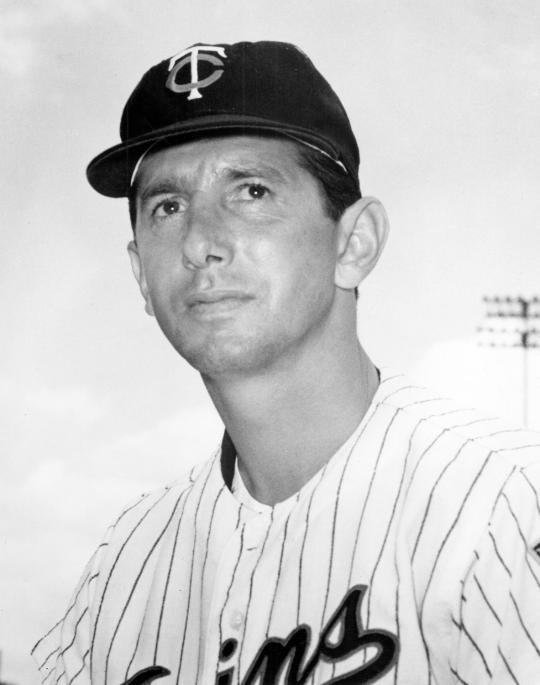

On this card, Grzenda’s facial features are so thin that his cheek bones seem to be protruding, accentuating the hollow look to the sides of his face. His long neck is also quite apparent, as is a close-cropped haircut that would have suited him to a stint in the military. There is also a trace of sweat on Grzenda’s face, an indication that he has just completed a workout on this day, sometime in the mid-1960s, at an unknown ballpark

Given his distinctive looks, it should come as no surprise that Grzenda’s nickname was “Shaky Joe.” He was known for being a whirl of nervous energy, a pitcher who seemed to be in perpetual motion. During his playing days, Grzenda drank two pots of coffee a day, and also had a reputation as a chain smoker, one who could plow through three packs of “Lucky Strikes” cigarettes in a 24-hour span.

The latter habit was most evident on days when Grzenda pitched. Sometimes he would light a cigarette in the dugout and start smoking, then leave the lit cigarette on the bench as he returned to the mound. Working at a frenetic pace that would have made Jim Kaat proud, Grzenda would try to finish off the opposing hitters as quickly as possible so that he could return to the dugout and finish the task of smoking the cigarette. Given all of this activity, it was no wonder that Grzenda sometimes appeared to be visibly shaking, even as he was catching a few breaths in the dugout.

Grzenda’s nervous exterior becomes more understandable when we examine his upbringing. He grew up in rural Pennsylvania, the son a coal miner. His father was a strict disciplinarian, a man who showed little patience with others and who often applied corporal punishment to his son.

Emerging from that difficult upbringing and those coal mines of the 1950s, Grzenda’s talents as a pitcher attracted the attention of several teams, including the Detroit Tigers. Not only was Grzenda a left-hander who threw hard, but he possessed a strong curve ball. He also had the kind of long, lean build preferred by most scouts.

After signing with the Tigers in 1955, Grzenda (pronounced Greh-ZEN-duh) struggled in his professional debut, but improved markedly in 1956 and ’57. By 1958, he was deemed ready for Double-A ball, pitching for the Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association. Adjusting quickly to Double-A and becoming popular with the fans of Birmingham, he went 16-7 with a 3.19 ERA and helped propel the Barons to the Southern Association pennant.

Based on his performance for the Barons, the Tigers intended to give Grzenda a long look during Spring Training in 1959. But during the winter, he came down with a case of appendicitis, delaying the start of his workouts. Trying to make up for lost time, Grzenda pushed himself too hard and injured his pitching arm.

The early-career arm injury cost Grzenda, who would never regain the popping fastball that he had shown in his first few minor league seasons. As a result of the setback with his arm, he would not make the Tigers’ roster until two years later. No longer a prized prospect by 1961, Grzenda had to settle for a role pitching in middle relief for the Tigers.

Grzenda made only four appearances for the Tigers, his ERA ballooning to 7.94. He spent most of that summer, all of 1962, and the first half of 1963 in the minor leagues. In the middle of the latter campaign, the Tigers released their fallen prospect.

Still only 27, Grzenda would find work with the Kansas City Athletics in February of 1964. The A’s assigned him to Birmingham, his original team. By coincidence, that season marked the return of professional baseball to Birmingham, which had gone without a team in 1962 and ’63. Birmingham had essentially lost its franchise after the ’61 season because of the city’s infamous “Checkers Rule.” It was a local by-law that prohibited black and white citizens from playing any sport or game together while within the city limits. The restriction included baseball, softball, football, basketball, dominoes, card games, and yes, even checkers.

In 1961, major league baseball had mandated that every minor league must be integrated. Given the enforcement of the Checkers Rule, it was impossible for Birmingham to comply with the new standards of Organized Ball.

With the Checkers Rule in effect for 1962 and ’63, Birmingham remained in baseball limbo. By the end of 1963, the city’s voters had voted out the infamous Theophilus “Bull” Connor, the commissioner of public safety and longtime supporter of the Checkers Rule. With Bull Connor out of power, Birmingham now operated under a system that featured a mayor and a city council. They repealed the Checkers Rule, clearing a path for baseball to return to Birmingham in 1964. A’s owner Charlie Finley gladly placed his Double-A affiliate in the Alabama city, which was now playing in the newly formed Southern League.

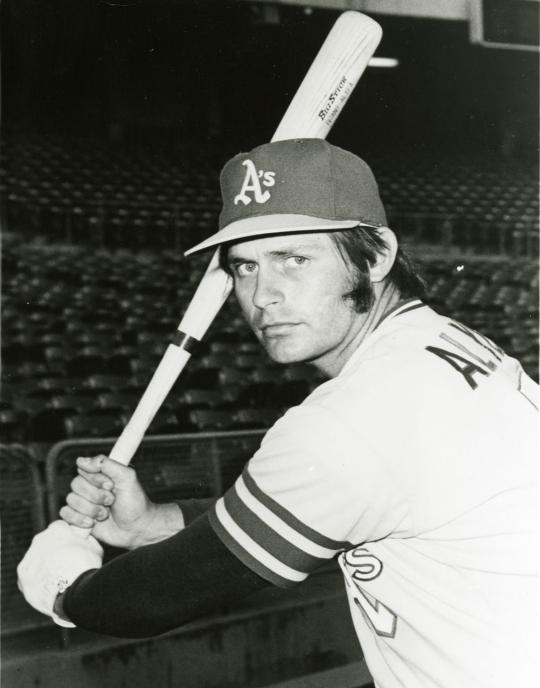

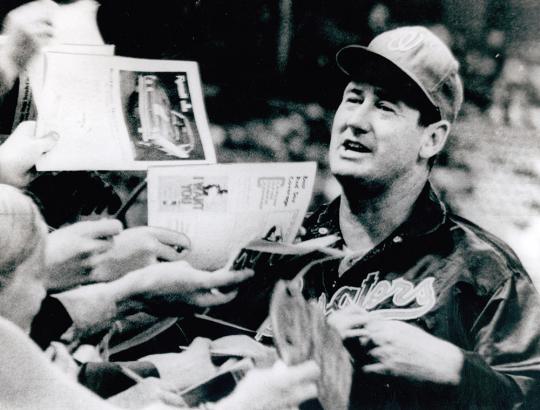

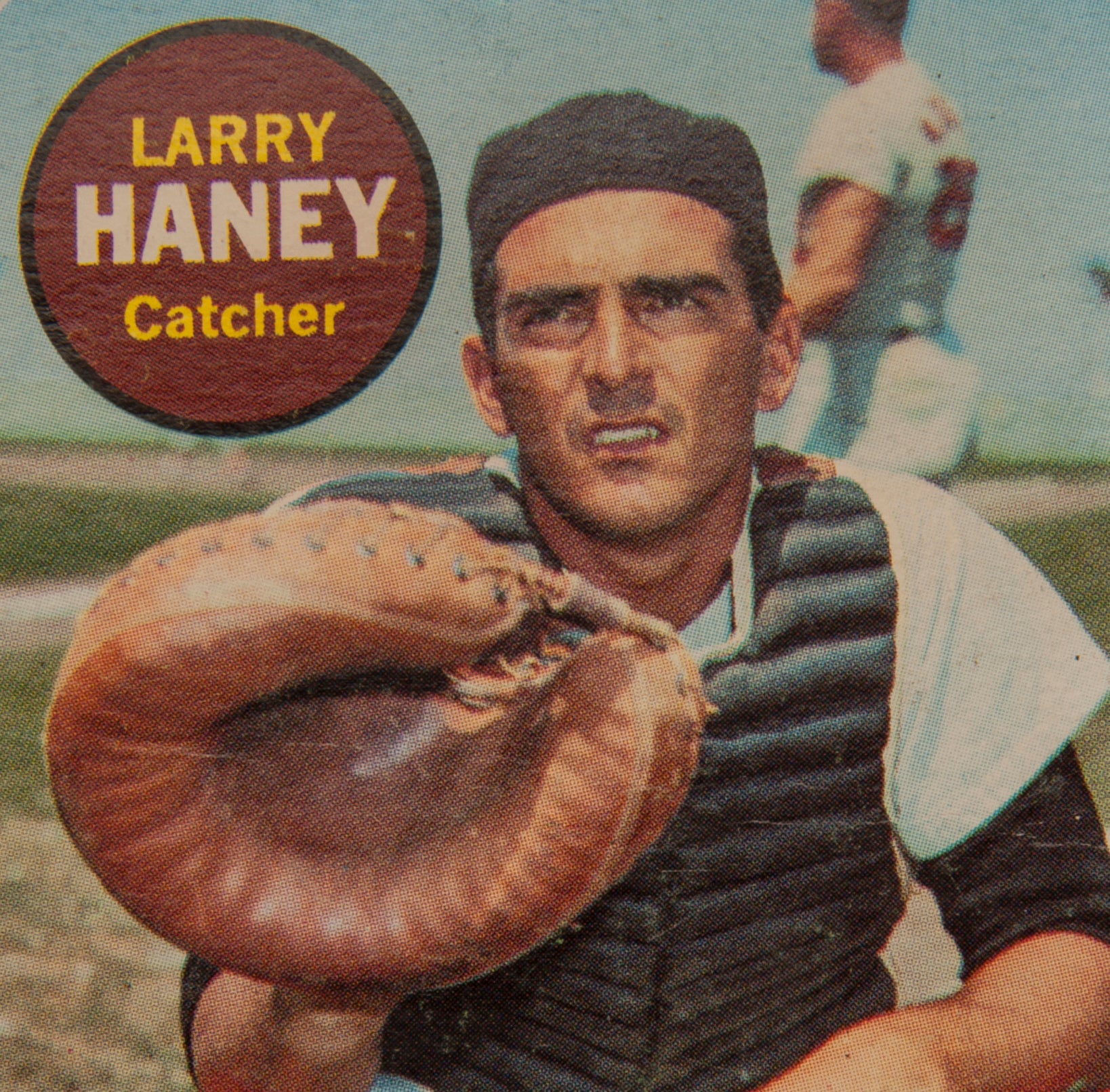

The top left-hander in Birmingham’s bullpen, Grzenda pitched well in the spring and earned a call-up to Kansas City in May. The move upset the Barons, a pennant-contending team what was losing arguably its best relief pitcher. Grzenda would appear in 20 games for the parent A’s but struggled with his control before being sent back to Birmingham in the middle of July.

Upset by the demotion, Grzenda considered quitting and going home to Pennsylvania. But the prospect of following in his father’s footsteps and working the coal mines did not appeal to him. Grzenda mulled the situation further, before electing to stick with baseball and return to the Barons.

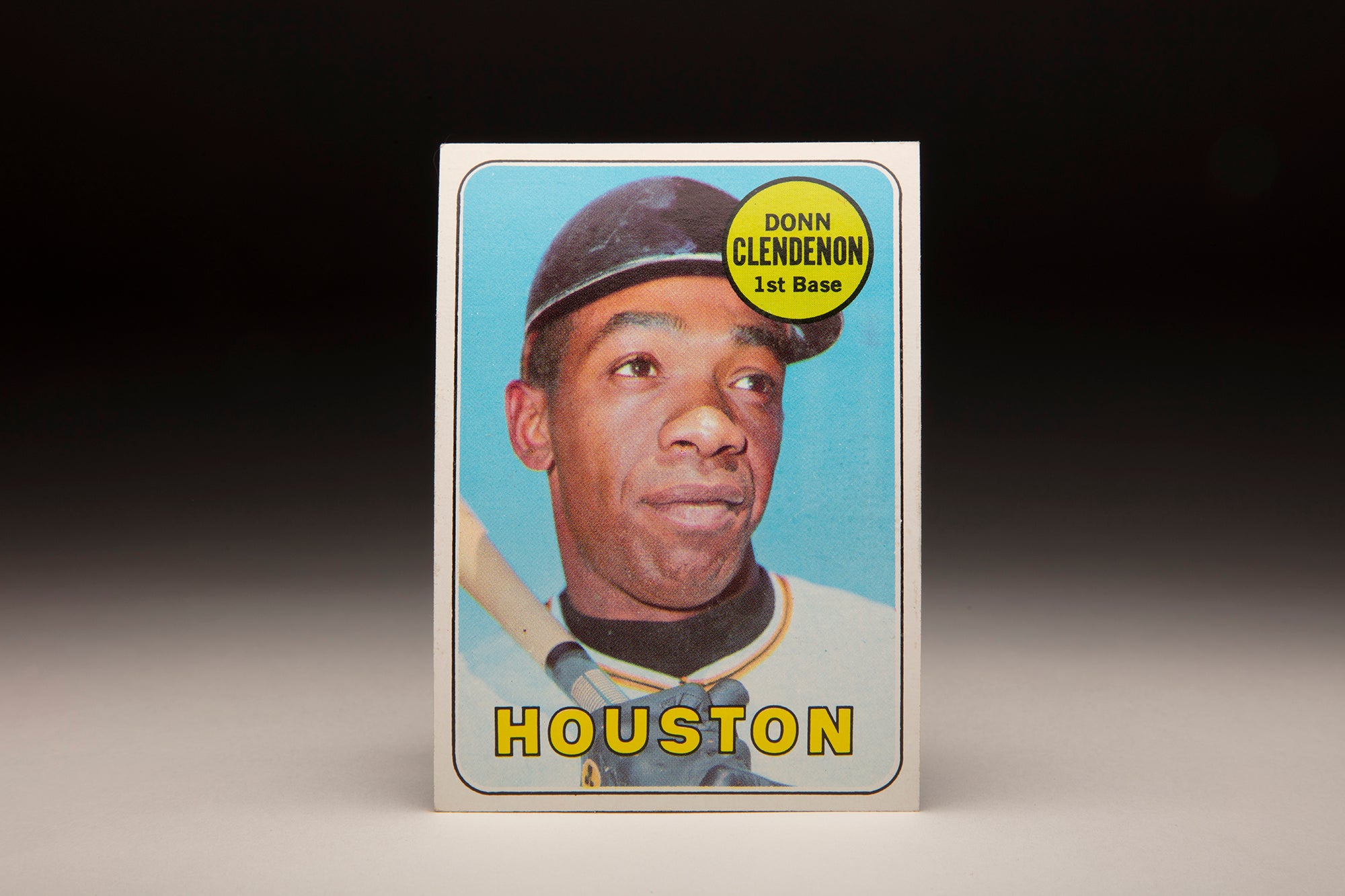

In 1965, Grzenda moved up to Triple-A and split his time between Vancouver and Oklahoma City, the latter team an affiliate with the Houston Astros. (In the 1960s, it was common for minor league players to be loaned out to other organizations for parts of the season.) The following year, Grzenda worked his way back to the A’s and appeared in 21 games, pitching effectively as a reliever.

Strangely, the 1966 season saw Grzenda back in the minor leagues. He made a return trip to the Southern League, this time pitching for the A’s new affiliate located in Mobile, Ala. Thanks to the addition of a new pitch, the palm ball, Grzenda allowed only 51 hits in 75 innings and finished a perfect 6-0.

Grzenda’s performance didn’t earn him a promotion to Kansas City, but did catch the attention of another major league team. The Mets, looking for relief help, purchased Grzenda from Finley and brought him to New York. He pitched in 11 late-season games out of the Mets’ bullpen, forging an ERA of 2.16.

Strangely, Grzenda’ late-season audition did not keep him in New York long-term. That winter, the Mets sold him to the Twins. He spent all of 1968 at Triple-A Denver, the Twins’ top affiliate in the American Association.

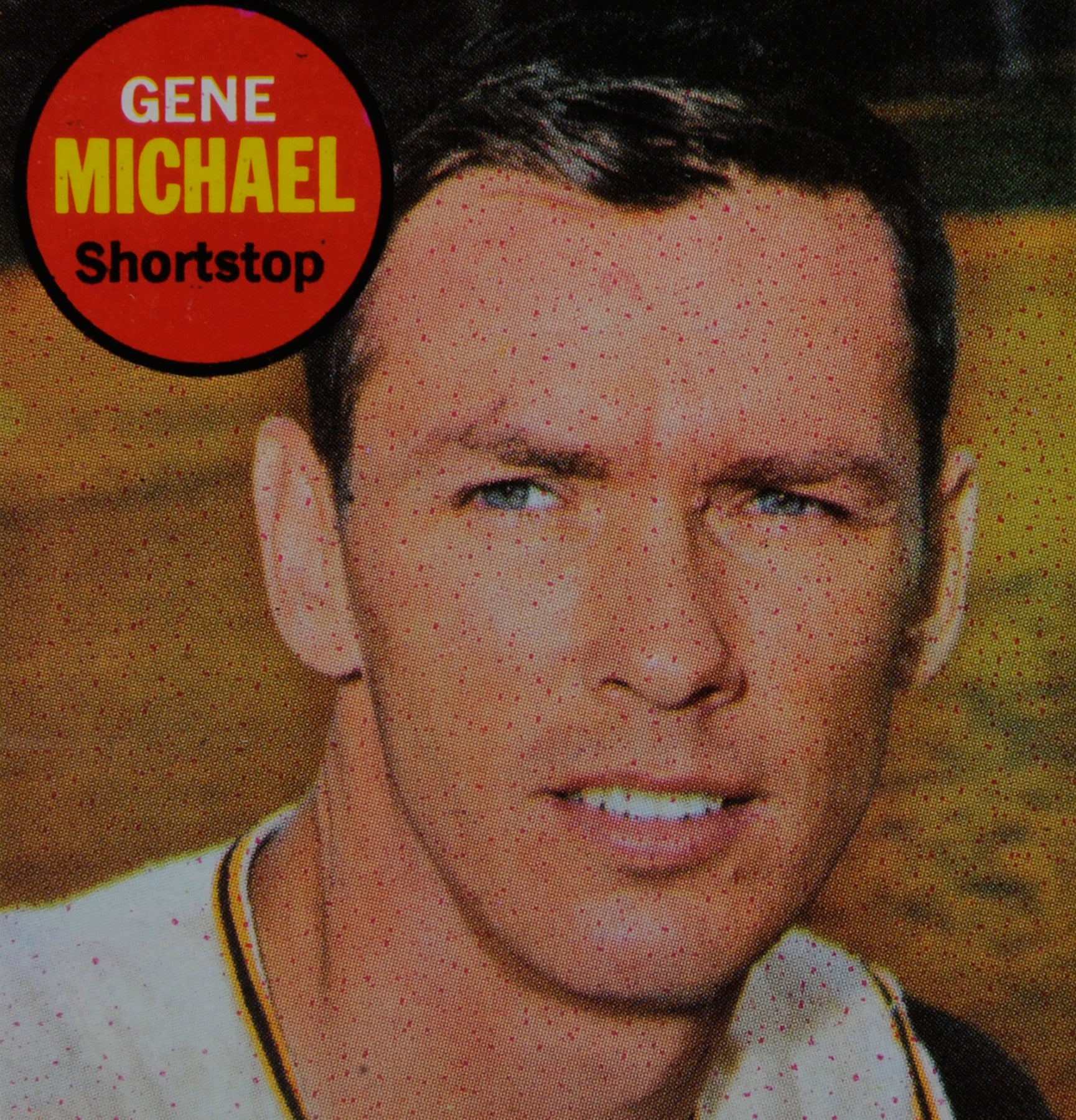

Even though Grzenda did not appear in a single major league game in 1968, Topps saw fit to include the veteran southpaw in its 1969 set. When Topps issued his new card, the company appropriately designated him as a member of the Twins, but the photograph was likely taken two to three years earlier, because of the ongoing dispute between Topps and the Players’ Association. If I were to guess, the photo was likely taken during the 1967 season, when Grzenda pitched for the Mets. He appears to be wearing blue pinstripes, which would match the colors used by the Mets at the time.

The designation of Twins on the card would prove prescient. Grzenda spent all of 1969 with the Twins, putting up a 3.88 ERA for manager Billy Martin. Grzenda’s season culminated in a scoreless appearance in the first-ever American League Championship Series, which the Twins lost to the heavily-favored Baltimore Orioles.

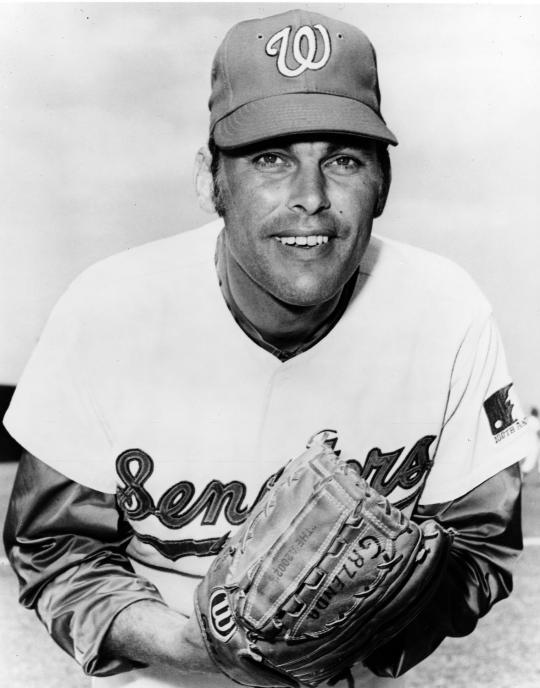

Grzenda reported to the Twins’ camp in the spring of 1970, but he would end Spring Training with a different organization. On March 21, the Twins traded Grzenda and another pitcher to the Washington Senators for slugging outfielder Brant Alyea. Grzenda pitched poorly for his new team, putting up a bloated ERA of 5.00 in 84 innings. But then came 1971, when Grzenda would rediscover both his control and command, becoming the team’s most effective relief pitcher. Although the Senators were a bad team in 1971, the 34-year-old Grzenda stood out as a bright spot. Displaying precise control, he posted an ERA of 1.92, won five games, and saved five more.

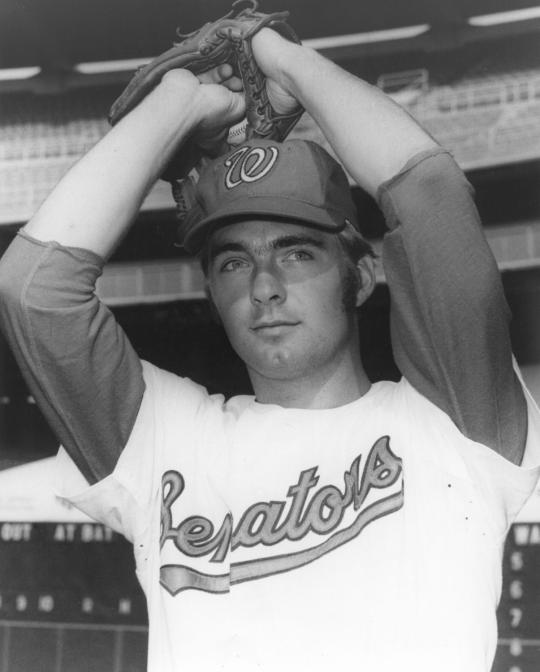

Grzenda provided some intangibles for the Senators, as well. He counseled some of the younger Senators pitchers, including a touted but nervous rookie named Pete Broberg, who was making his first appearances in the major leagues.

“Joe came to my aid, calmed me down,” an appreciative Broberg told writer Chic Feldman of The Scrantonian.

Although Grzenda pitched well in ’71, the many address changes – and the minor league bus rides – of his long career had left him somewhat jaded, but still with a sense of humor.

That summer, Grzenda delivered this famous line to the Sporting News, one that received some humorous attention throughout the game. “I’d like to stay in baseball long enough to buy a bus,” Grzenda said, “then set fire to it.”

As the ’71 season moved into its final days, Senators owner Bob Short delivered a major announcement, making it publicly known that he planned to move the team to Texas. It was a decision that angered the fans in Washington.

As circumstances would have it, Senators manager Ted Williams called upon Grzenda to try to save the final game at RFK Stadium.

With the Senators holding a 7-5 lead against the New York Yankees, Grzenda entered the game in the ninth. He retired Felipe Alou on a routine grounder and then handled Bobby Murcer, who bounced back to Grzenda. He was now one out away. A fast worker to begin with, Grzenda also sensed that there was discord among the fans in attendance at RFK Stadium. So he yelled out to the next Yankees batters, Horace Clarke, telling him to hurry up and assume his place in the batter’s box.

“He took a lot of practice swings,” Grzenda told the Washington Times in recalling the moments leading up to Clarke beginning his at-bat. By now the angry fans at RFK, some of whom had hung Short in effigy during the game, had reached a state of frenzy. Some of the Washington fans started to make their way onto the playing field. “I saw the dust coming up from the first base side,” Grzenda told The Times. “The fans jumped the fence and kept coming.”

One of the fans, a very large man sporting a full beard, made a beeline toward Grzenda. For a moment, Grzenda thought the oversized intruder was preparing to tackle him, but when he arrived at the mound, the fan only wanted to touch the left-hander on the shoulder.

In the meantime, Grzenda noticed that a crowd was developing around the Senators’ first baseman, the 6-foot-8 Frank Howard.

“I remember seeing three people on Frank Howard’s back,” Grzenda told The Scrantonian. I don’t know how they got there. He just dumped them and kept on moving.”

While the mammoth Howard was able to handle his situation with relative ease, Grzenda noticed additional company coming his way. A large swarm of fans had gathered around him on the mound. Wisely, Grzenda decided to flee the area. He ran off the field at RFK Stadium, finding the relative safety of the dugout on his way to the clubhouse.

The rioting by the fans would prevent Grzenda from throwing another pitch that night. With thousands of fans scattered throughout the field, which was now rendered unplayable, the umpires called the game a forfeit, giving the Yankees a victory.

According to the forfeit rule, the game was scored officially as a 9-0 Yankee victory. For Grzenda, there would be no chance to save the final game of the Senators, and no chance to ring out RFK Stadium on a high note.

Even amidst the chaos, Grzenda was wise enough to hold onto the ball that he had thrown for the final pitch. He took the ball home with him and placed it in a drawer with some other memorabilia, keeping it there for nearly three and a half decades.

After the ’71 season closed out, Grzenda hoped to remain with the relocated franchise, in part because he enjoyed playing for Ted Williams. “Ted kept us loose,” Grzenda told the Washington Times. “I loved playing for him. You’d sit there and listen to his stories.”

Against his wishes, Grzenda’s association with Williams would come to an end. After Grzenda went home to resume his offseason job as a deputy sheriff in in Daleville, Pa., he received a call from St. Louis Cardinals general manager Bing Devine. “Welcome to the club,” Devine told Grzenda, informing him that had just been traded to the Cardinals in exchange for utility infielder Ted Kubiak.

Unable to match his success of 1971, Grzenda struggled in St. Louis. In 1973, he received an invite to Spring Training with the Yankees, but did not make the Opening Day roster, instead spending the season at Triple-A Syracuse.

He then moved on to the Atlanta organization in 1974 and pitched the season at Triple-A Richmond before deciding to retire.

After his playing days, Grzenda went to work for a company called Gould Battery. He also ran for county commissioner near his hometown, but lost the election. He is now enjoying retirement in Daleville.

Although Grzenda had thrown the final pitch in the history of the Washington Senators, he had never been given the chance to register that elusive final out for the franchise.

In the spring of 2005, the newly relocated Washington Nationals tried to rectify the situation. Fresh off their move from Montreal, the newly minted Nationals invited Grzenda to participate in their inaugural Opening Day ceremony, scheduled for the old RFK Stadium. It was an idea that had been suggested by Grzenda’s son. Both the Nationals and the elder Grzenda agreed to the suggestion.

When the Nationals asked him to participate in ‘05, Grzenda produced the ball from the 1971 finale and brought it back to RFK. Grzenda walked from the Nationals’ dugout toward the infield, handing the ball off to President George W. Bush, who was in attendance for the Nationals’ opener.

The President then threw out the ceremonial first pitch.

The event brought Grzenda full circle, something that seems to happen so often in our game. A man who had to travel more than most, Grzenda played for 18 professional teams over the span of 20 seasons.

His career was an eventful one, including time with the team that brought integrated baseball to Birmingham and the team that said farewell to Washington – before Joe Grzenda helped celebrate its return some 34 years later.

Grzenda passed away on July 12, 2019.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame