- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Donn Clendenon

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Donn Clendenon

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

The 1969 New York Mets figure to be a frequent topic of conversation in 2019. No fewer than three different books about the team are scheduled for release this spring and summer, and the Mets themselves have planned an elaborate celebration of that championship team, which pulled off arguably the greatest upset in World Series.

For many Mets fans, the members of the ’69 team remain the darlings of a franchise that was born in 1962.

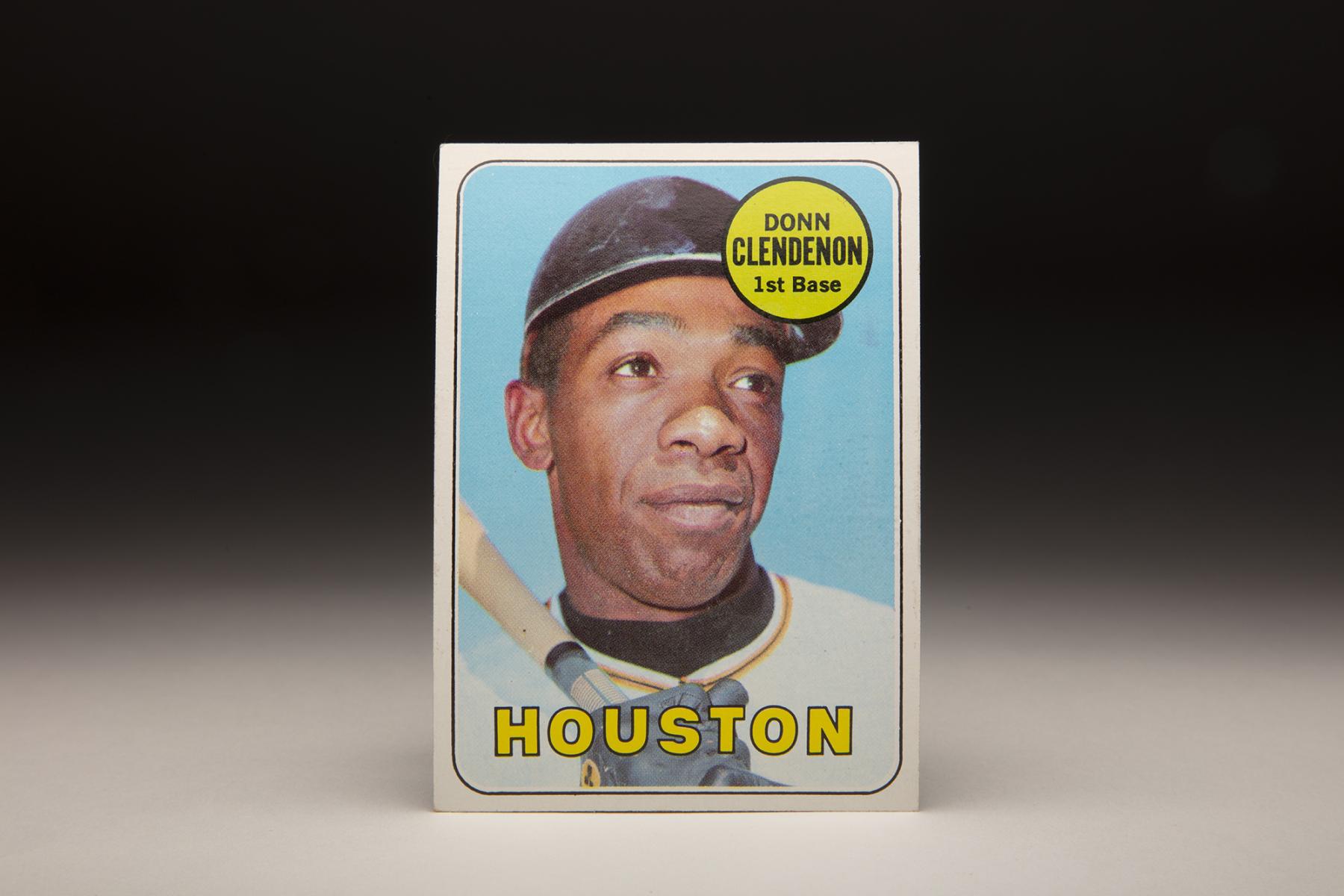

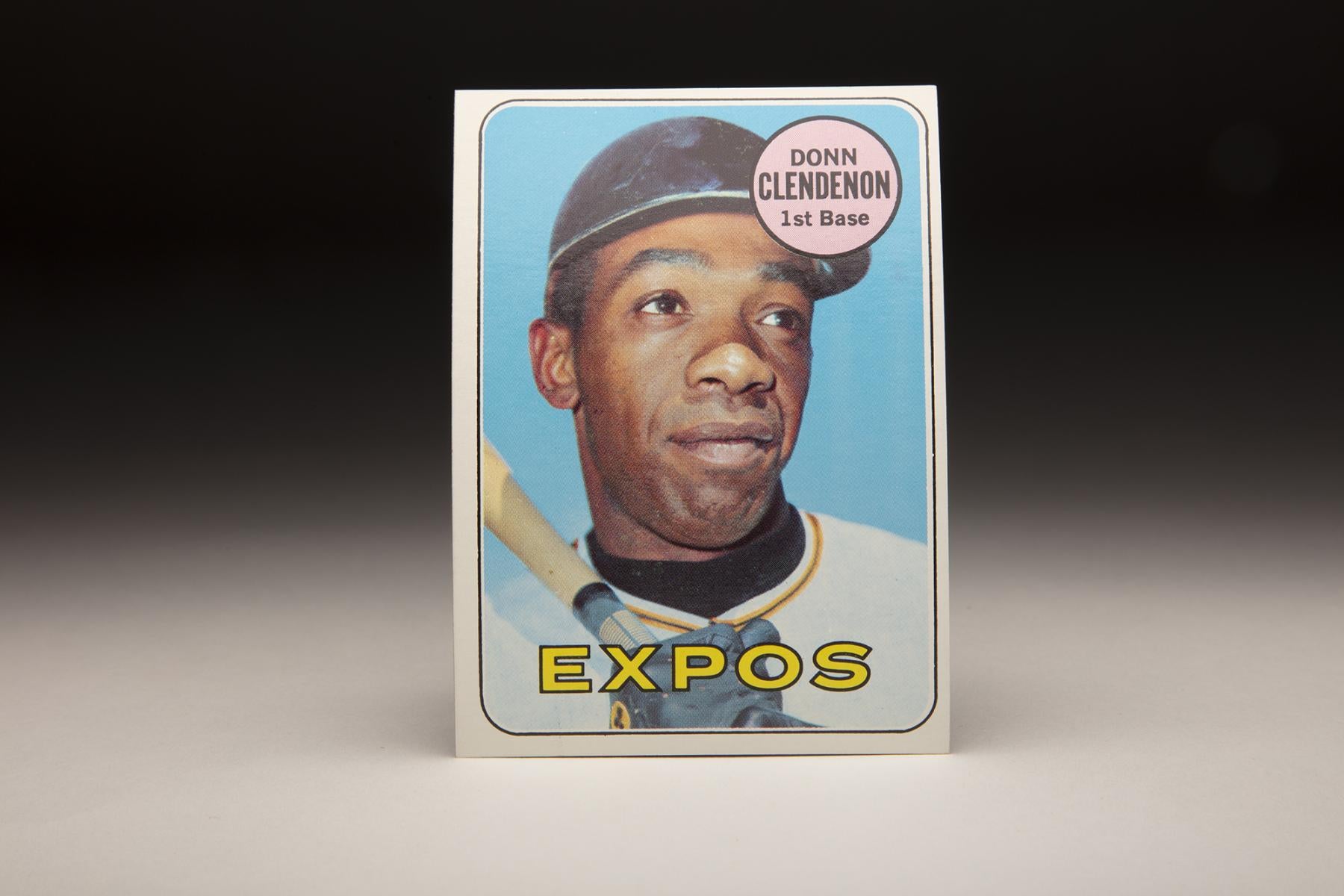

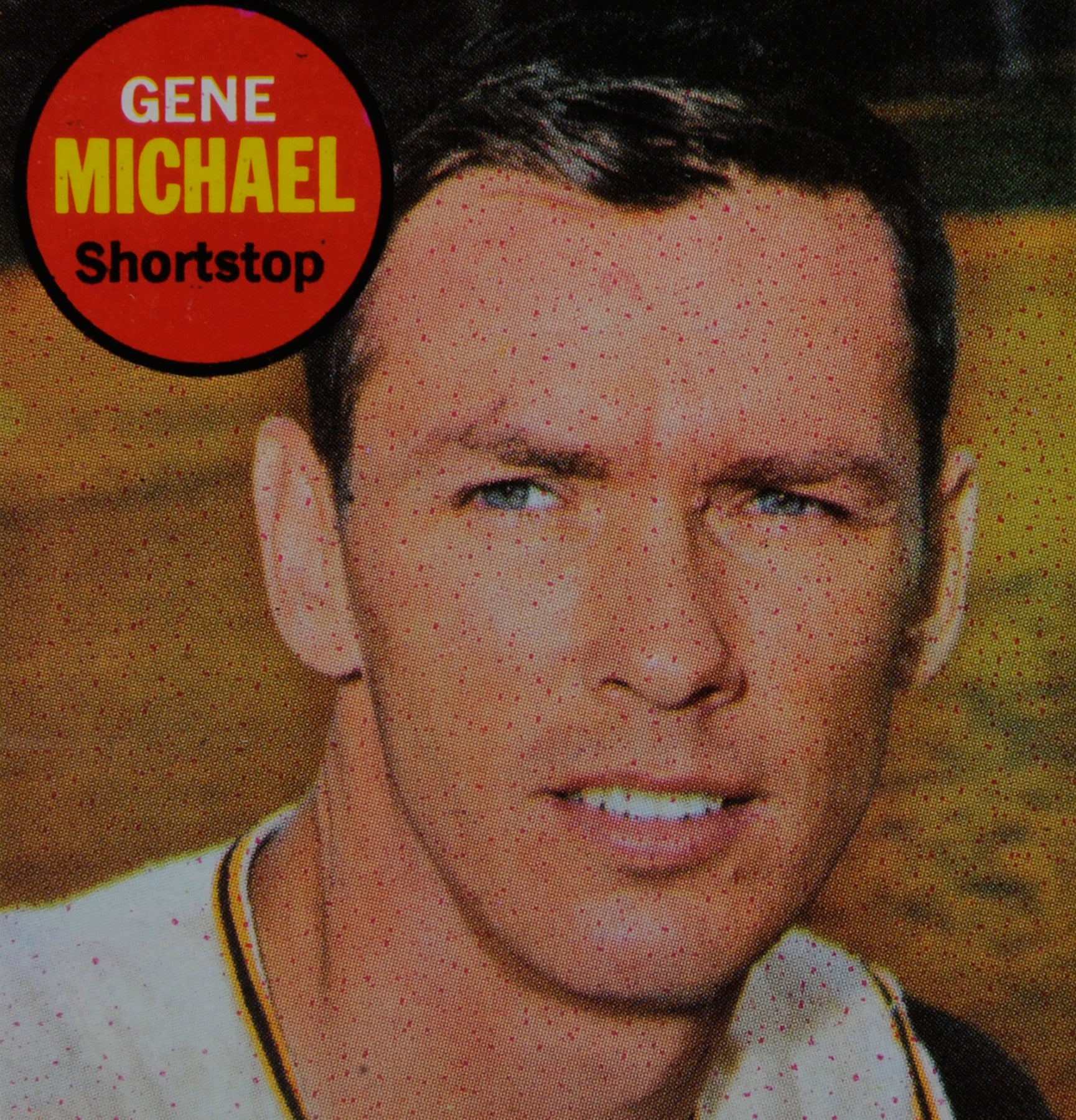

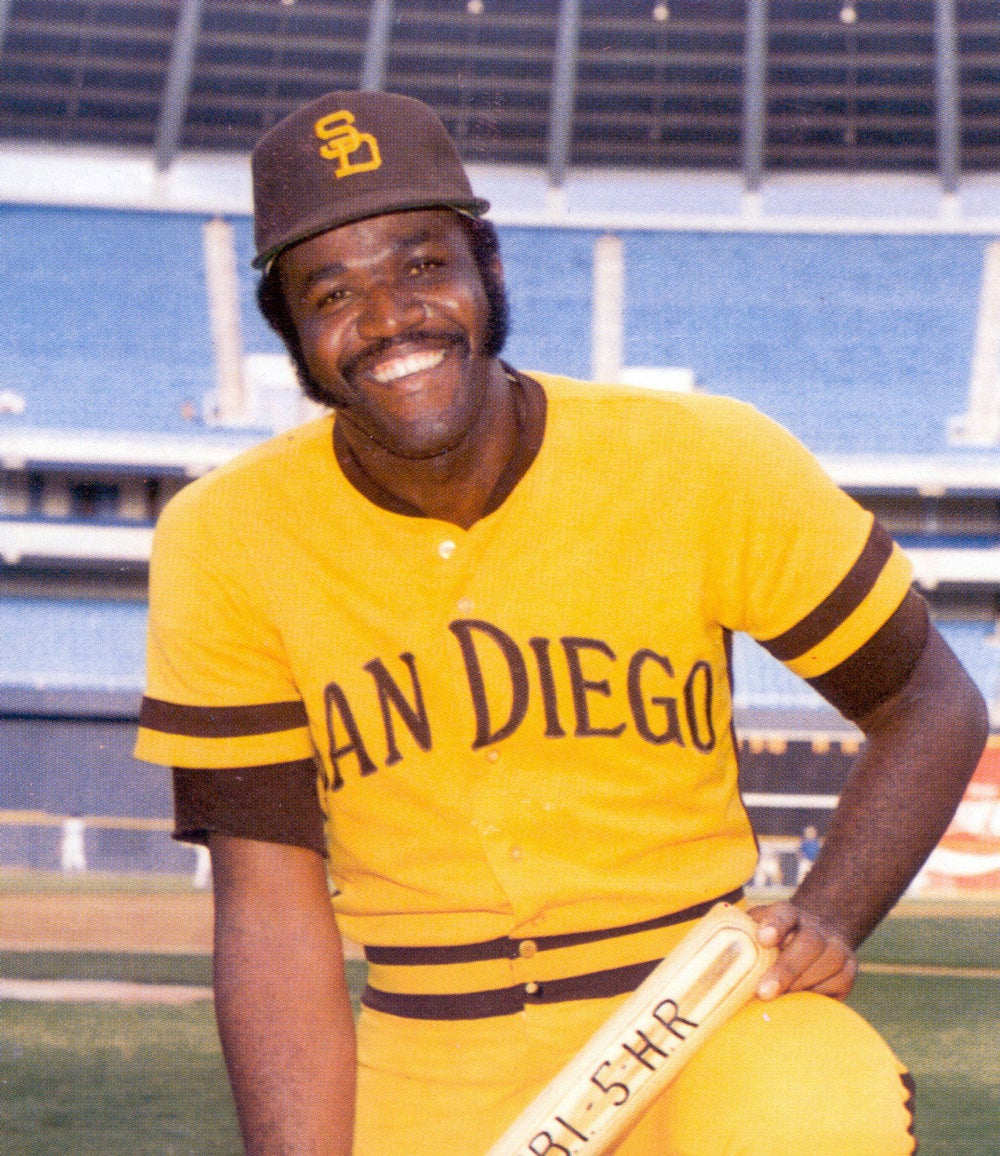

It’s quite possible that the ’69 Mets would not have won it all without the contributions of one Donn Clendenon. Rather curiously, he appeared on two versions of Topps cards in 1969, but as it turned out, neither designated him as a member of the Mets. The first card shows him as a member of the expansion Montreal Expos, while the second one places him with the Houston franchise – not the “Astros,” but “Houston.”

We’ll explain why the word Astros is not included on the card, but we’ll have to tackle that later. First, let’s try to answer the more pertinent question: Why are there two versions of the Clendenon card?

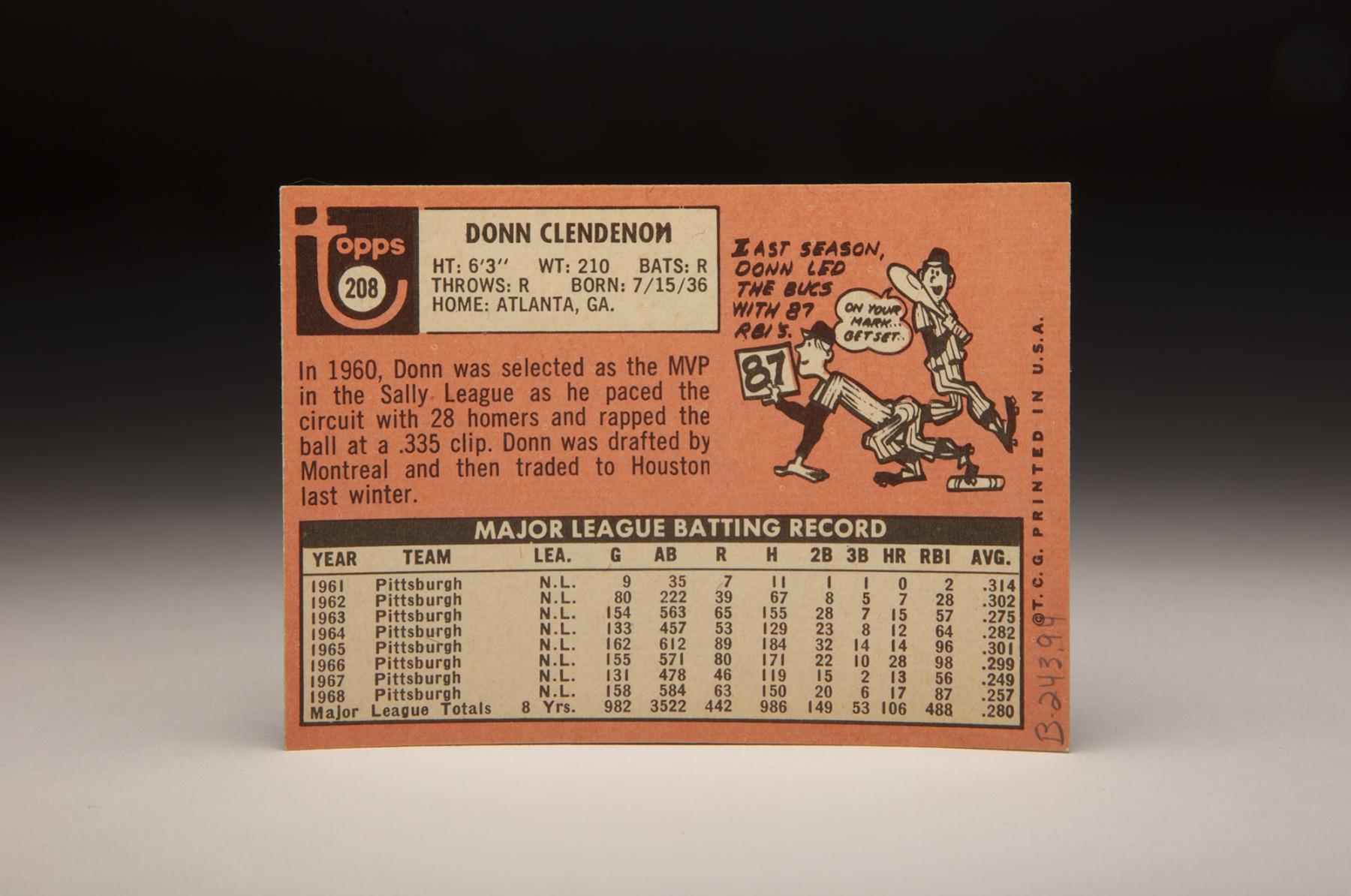

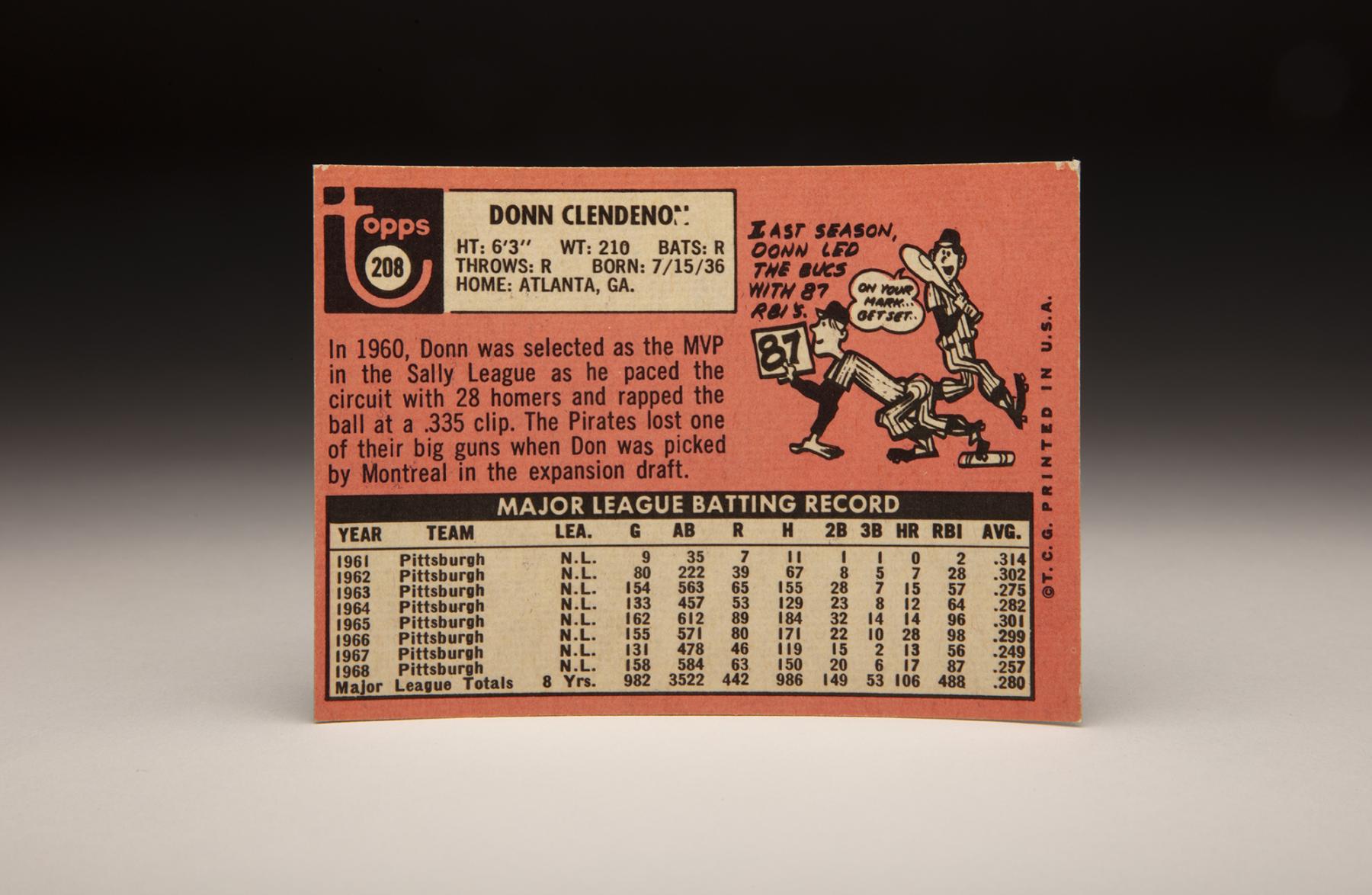

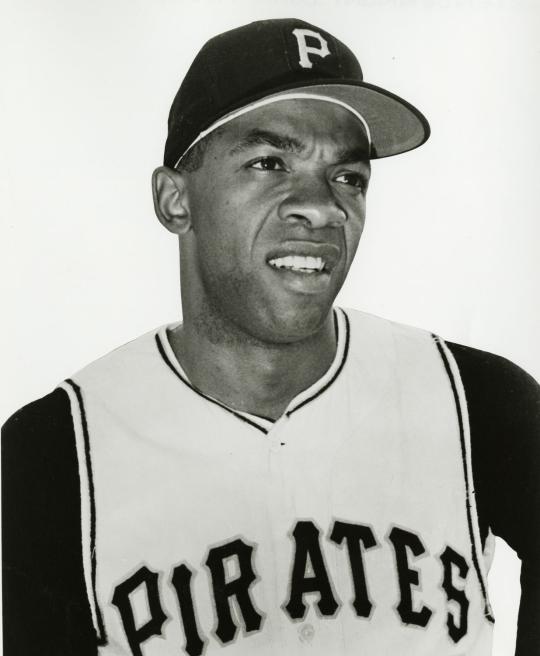

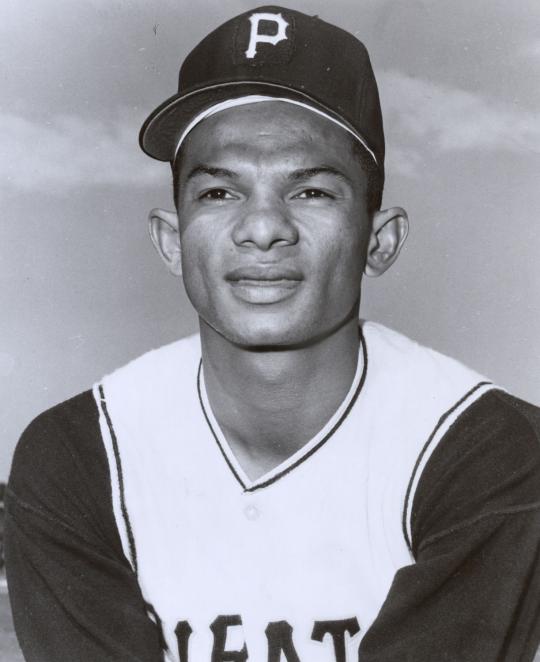

To begin with, Clendenon actually spent the 1968 season with the Pittsburgh Pirates. The photograph, which may have been taken two or three years prior to 1969, features the black and gold jersey colors of the Pirates, along with a black Pirates helmet, with the gold-colored logo obliterated. After somewhat of an off year at the plate in 1968, the Pirates decided to leave Clendenon unprotected from the expansion draft, allowing the Expos to select him.

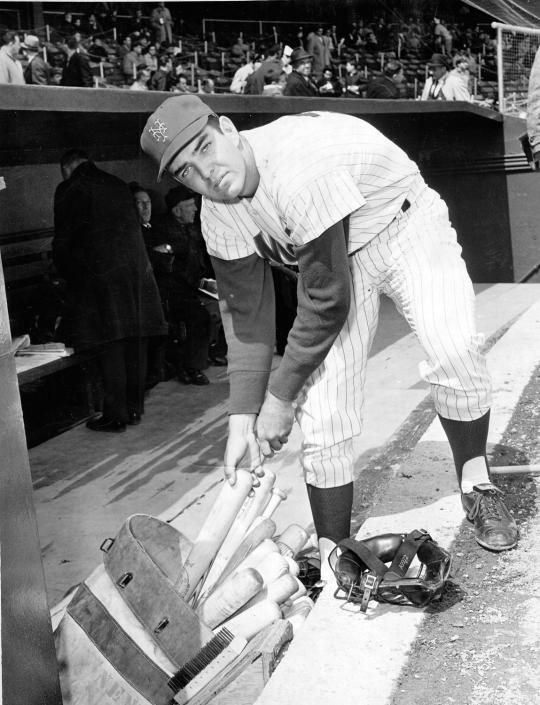

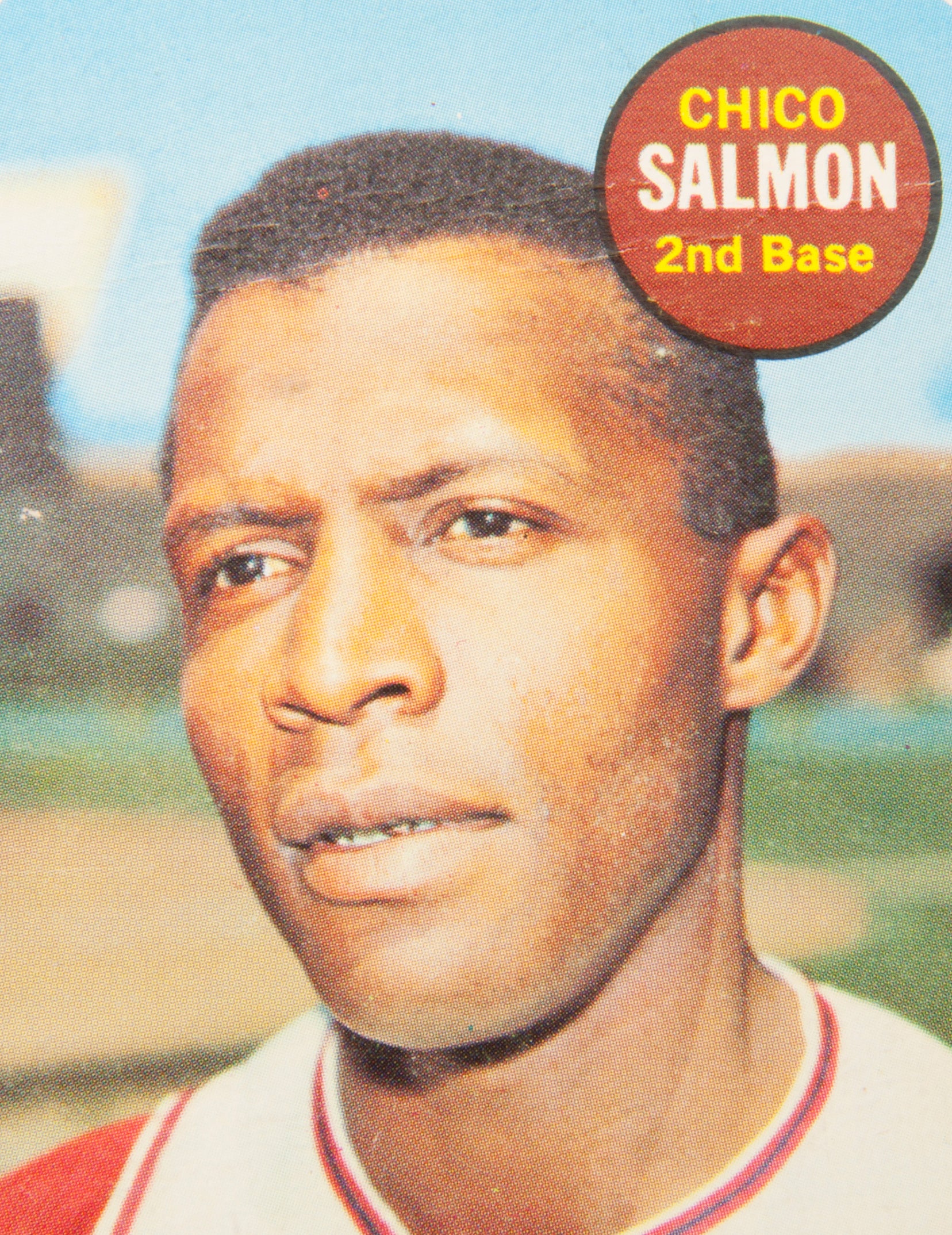

Though Clendenon was a well-respected, established power hitter, he was also 32 years old and coming off a season in which he led the National League in strikeouts. The expansion Expos wanted younger players, so they soon worked out a trade. In January of 1969, the Expos sent Clendenon and outfielder Jesus Alou to the Houston Astros for star first baseman/outfielder Rusty Staub, who was still only 24. The Expos rightly considered the deal a major coup. And Topps eventually produced an updated card of Clendenon, one with the same photo but which now listed “Houston” as his team.

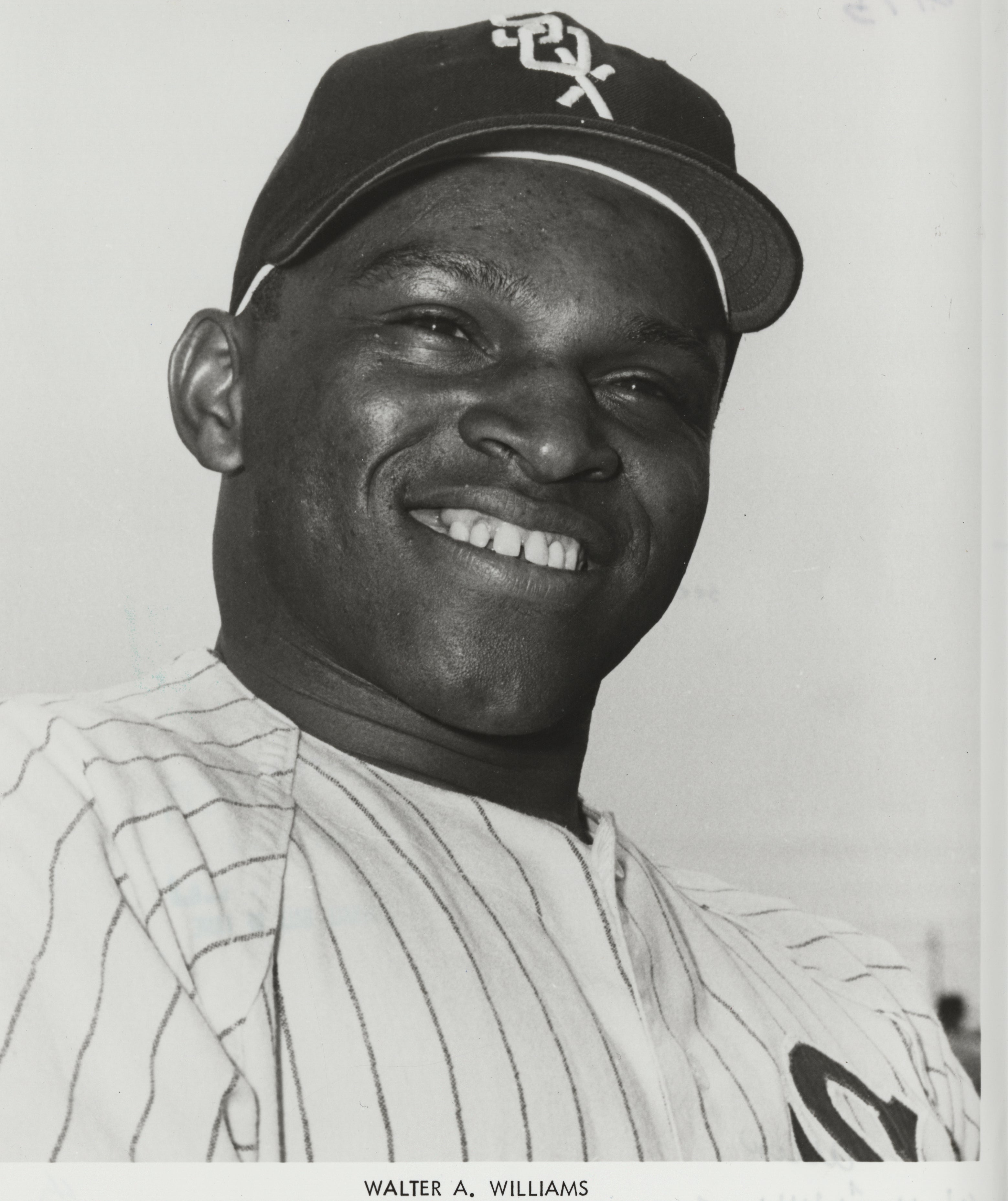

There was one problem with the trade. On Feb. 28, Clendenon announced that he did not want to play for Houston. In actuality, he did not want a reunion with manager Harry Walker, based on his previous experiences playing for “The Hat” in Pittsburgh. Fairly or not, Clendenon believed that Walker did not treat his Black players as well as his white players. Initially, Clendenon said only that he was unhappy with his salary and the general terms of his contract, but in later years he admitted that Walker’s presence in Houston had been a major factor. On March 2, Clendenon announced that he had decided to retire from baseball and would begin working fulltime for the Script Pen Company based in Atlanta, where he lived during the winter. This decision disappointed the Astros, who had traded a young star like Staub for a veteran player who had no interest in joining the team. The Astros asked Major League Baseball to intervene. On March 8, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn ruled that he was “rejecting” Clendenon’s retirement and that the trade between the Astros and Expos would stand. In the meantime, Kuhn asked one of his assistants, Monte Irvin, to visit Clendenon at his Atlanta home. Irvin and Clendenon talked for several hours. According to an interview that Clendenon did years later with Phil Pepe of the New York Daily News, Irvin “helped me see things in a different light.”

On April 2, Clendenon announced a change of mind. He was still not willing to play for the Astros, but would report to Montreal. He told the Expos that was ending his retirement and was now willing to sign a contract for the 1969 season. Gaining approval from the Commissioner’s Office, Clendenon reported to the Expos’ Class A farm team in West Palm Beach, where he would spend the next two weeks working out and preparing himself to return to the major leagues.

With Clendenon now a member of the Expos, the Astros needed to be compensated for the loss of the slugger. On April 9, the two teams reached an agreement: Clendenon would stay with the Expos, who in turn would send $100,000 and two young pitchers, Jack Billingham and Skip Guinn, to Houston as compensation. Given all of this tumultuous activity, it’s highly appropriate that Clendenon has somewhat of a confused look on both versions of the Topps card. Confusion, along with uncertainty, represented a major theme to Clendenon’s 1969 season.

Now, what about the strange designation of “Houston” on the 1969 card? On most of its ’69 cards, Topps showed the team nickname at the bottom of the card. But rather curiously, with the Astros players, Topps left out the word “Astros” and instead used the city name of Houston at the bottom. Topps did this because of a dispute that had started in 1968 between the Astros and the Monsanto Company, which produced Astroturf, the playing surface used at the Houston Astrodome.

The two organizations became engaged in a legal battle over who had the legal rights to the name of “Astroturf.” Preferring to take a cautious approach and hoping to avoid any involvement in the conflict, even tangentially, Topps decided to remove “Astros” from all of its cards. As a matter of fact, Topps had done the same thing with its 1968 Topps set. It was not until 1970 that Topps restored the word “Astros” to its cards, ending the two-year absence.

In the meantime, the Mets observed the Clendenon situation from afar. The Mets probably had little idea at the time, but Clendenon’s brief retirement and his subsequent return to Montreal would eventually pay off for the New Yorkers. Clendenon did not hit well in Montreal, leading to sporadic playing time. Clendenon complained about the situation, which pushed the Expos into pursuing another trade.

At the June 15th trading deadline, the Expos agreed to a deal with Mets general manager Johnny Murphy, who asked to speak to Clendenon. When the slugger assured Murphy that he was committed to play baseball, Murphy agreed to the trade. The five-player transaction made Clendenon a Met in exchange for four minor league players: Infielder Kevin Collins and three pitchers, the best of whom would turn out to be Steve Renko.

Freed from irregular playing time with an expansion team, Clendenon happily joined the Mets, at first becoming a platoon partner with Ed Kranepool at first base. The addition of Clendenon strengthened the Mets’ lineup against left-handed pitching while also giving manager Gil Hodges an important weapon off the bench. In due time, Hodges would turn to Clendenon as his everyday first baseman.

In 72 games with the Mets, Clendenon slugged .455 while accumulating 12 home runs and 37 RBI. These were solid numbers, especially for a Mets team lacking in power, but they were hardly overwhelming. In some ways, it was the timeliness of Clendenon’s hitting that mattered most; he hit seven home runs in September, as the Mets overcame a five-game deficit at the beginning of the month on their way to beating back the favored Chicago Cubs.

More significantly, Clendenon saved his best hitting for the postseason. He did not play against the Atlanta Braves in the NLCS, but became the centerpiece of the Mets’ offense during the World Series against the powerhouse Baltimore Orioles. In a Game 1 loss, Clendenon delivered a double and a single. He then contributed to a victory in Game 2, launching a solo home run in a tight 2-1 decision. Clendenon would hit two more home runs, one in Game 4 and another in Game 5, as the Mets finished off a remarkable five-game win over the vaunted Orioles. While the Mets probably could have won the National League East without Clendenon, they would have been harder-pressed to overpower the talented Orioles without the power and the clutch hitting of their veteran slugger.

After Game 5, the media named Clendenon MVP of the Series, an award that brought with it a new Dodge Challenger. The slugging first baseman remained typically humble.

“There is no most valuable player on this team,” he told the assembled writers. “We’ve got lots of them.”

While Clendenon downplayed his impact, both in terms of the World Series and the regular season, his teammates felt otherwise. The most famous of the ’69 Mets said that Clendenon changed the attitude of the clubhouse.

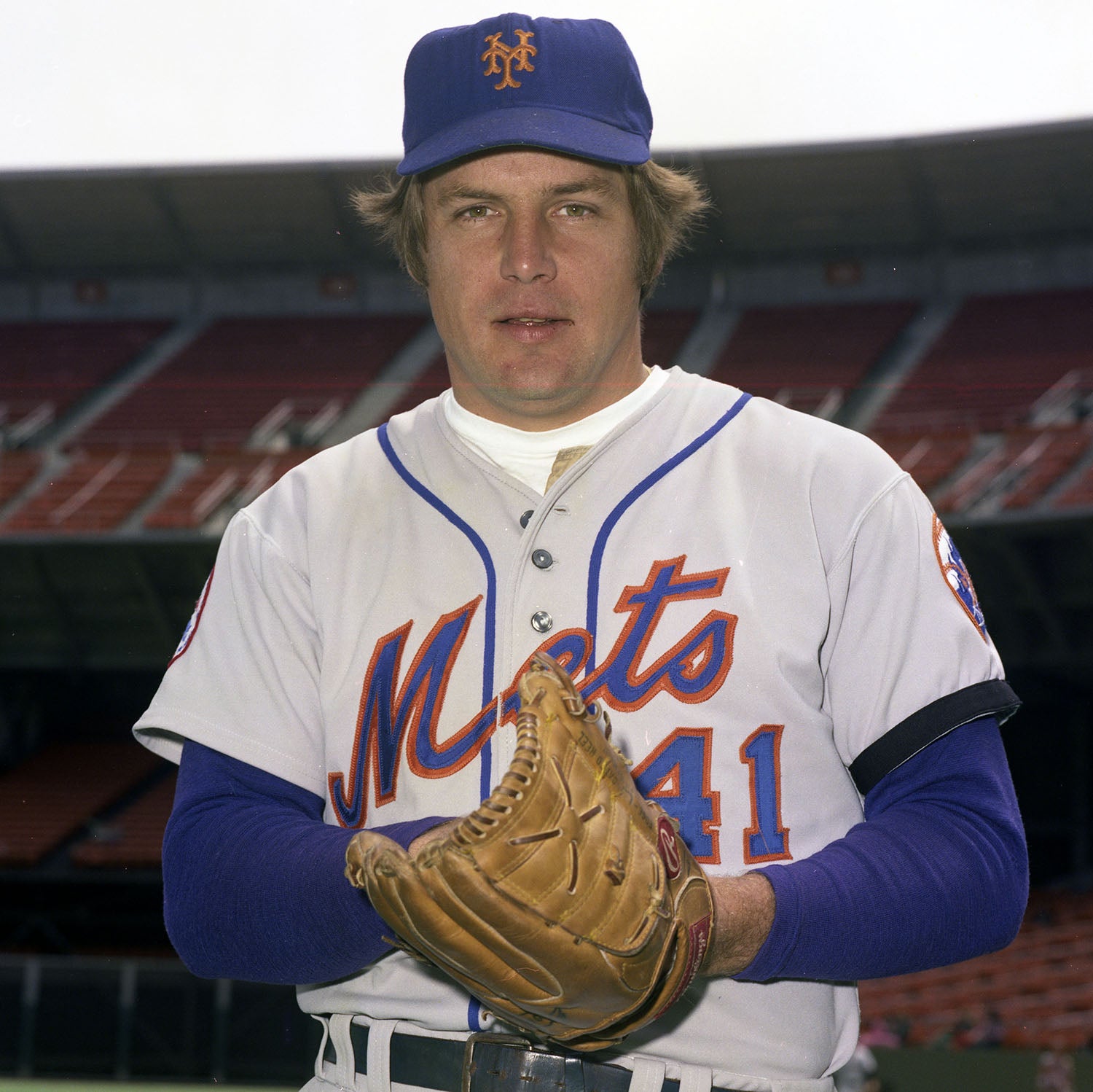

“He gave us something we never could have understood before he got there,” Hall of Famer Tom Seaver said in a 2003 interview with the New York Post. “And that’s an understanding that we didn’t have to apologize for being where we were, no matter that we were the Mets and nobody believed we belonged in that race. Don’t say [something like] that when Donn’s around.”

Clendenon’s 1969 season is the most well-known chapter of his career. But that career was shaped by his upbringing in segregated Atlanta, where he grew up without knowing his father, a victim of leukemia at an early age. Clendenon subsequently matriculated at Morehouse College, a prestigious all-Black school located within the city. Clendenon starred in football, basketball, and baseball at Morehouse, where his mentor was none other than school alumnus and civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., a close family friend of the Clendenons.

After graduating from the college in 1956, Clendenon took a job as a high school teacher, but his baseball exploits at Morehouse did not go forgotten. Branch Rickey, the president of the Pirates, met Clendenon at a banquet and convinced the youngster to attend a 1957 tryout camp. Based on his performance at the camp, including an impressive show of both power and speed, Clendenon received a contract offer from the Pirates and accepted an assignment to play at Jamestown of the NY-Penn League.

Clendenon continued to teach part-time during the winter, while progressing steadily through the Pirates’ farm system. Life in the minor leagues proved difficult, especially in light of Jim Crow segregation that directly affected African-American players. One season, while playing for Jacksonville, Clendenon and the team’s other Black players had to live in rooms located above a boisterous nightclub, where music played to all hours. At another point, Clendenon played for a team called the Wilson Togs in the Carolina League. With nine Black players on the team’s roster, a local newspaper referred to the team as the “Black Togs.” Shortly thereafter, Clendenon found himself demoted to a lower league, as a way of reducing the number of Blacks on the Wilson team. Clendenon was so discouraged that he thought of quitting, before changing his mind.

By 1961, Clendenon made it to Triple-A ball at Columbus. When the Triple-A season ended, he received word of a call-up to Pittsburgh. The Pirates gave him a look in nine September games, and Clendenon responded by hitting .314 and drawing five walks in 40 plate appearances.

That audition did not, however, guarantee Clendenon a spot on the Pirates’ Opening Day roster in 1962. Instead, he went back to Columbus for more seasoning. He didn’t need much, batting an even .400 in a dozen games and earning a quick recall to Pittsburgh – this time for good. Clendenon eventually took over at first base for Dick Stuart, hitting .302 and compiling an OPS of .853 in 80 games. Clendenon’s second-half surge earned him second place in the National League Rookie of the Year balloting.

In 1963, Clendenon played in 154 games for the Pirates. He struck out 136 times, a point of concern, but did hit 15 home runs while also stealing 22 bases, the latter number showcasing an unusual attribute for a first baseman. For the next five seasons, Clendenon remained the Pirates’ first baseman. Initially, his home run totals lagged, largely because of the vast dimensions of Forbes Field, but he burst out in 1966, clubbing 28 home runs.

Clendenon’s production dipped in 1967 and ’68. The latter season was especially difficult, for reasons having nothing to do with baseball. Just prior to Opening Day, Clendenon learned about the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., his close friend and onetime mentor. Faced with the prospect of playing their first two regular season games a few days after the assassination, Clendenon and several other Pirates led an effort to postpone the games. The Pirates players released a written statement: “We are doing this because we respect what Dr. King has done for mankind. Dr. King was not only concerned with Negros or whites but also poor people. We owe this gesture to his memory and his ideals.”

Later in 1968, another tragedy affected Clendenon when he lost his ailing stepfather, Nish Williams, the man who had helped raise him after the death of his father. Perhaps bothered by such real life events, not to mention the booing that he heard from some Pittsburgh fans, Clendenon played well below his usual norm in 1968, leading to the frenetic upheaval of his 1969 season.

After helping the Mets win the World Series, there was no letdown for Clendenon in 1970. Although the Mets failed to repeat as National League East champs, Clendenon put together a productive season as the team’s regular first baseman, batting .288 with 22 home runs. It was his best year since 1966, and helped him finish 13th in the league’s MVP vote.

Clendenon’s situation began to change in 1971. He lost the first base job to Kranepool, who compiled a .340 on-base percentage and hit 14 home runs. With Kranepool on the scene, and two young prospects, John Milner and Mike Jorgensen, showing promise, the Mets suddenly had a glut of first basemen. After the season, the Mets made room for their youth by releasing Clendenon.

In December, Clendenon found work with the St. Louis Cardinals. But he was now 36 and unable to wrest the Redbirds’ first base job away from Matty Alou, his onetime teammate in Pittsburgh. Rendered a bench player in 1972, Clendenon drew his release on Aug. 2. The release ended Clendenon’s career.

Clendenon left baseball and continued to work for the Scripto Pen Company before joining General Electric. With GE, he became the organization’s recruiter of minority job candidates.

After a few years, he decided to return to Duquesne University, where he had earlier pursued his law degree. He completed his degree in 1978, passed the bar exam, and eventually became a partner in a firm specializing in criminal law.

Given his intelligence and ambition, Clendenon seemed like he was headed toward a long and successful post-baseball career.

But at the age of 50, he became involved with cocaine, an addiction that led to his decision to enter a drug rehabilitation facility. As part of his treatment, he underwent a thorough physical examination. Doctors discovered an abnormality with his blood, indicating that he had leukemia. It was the same illness that had taken his father so many years earlier. To his credit, Clendenon did not give up. He moved to Sioux Falls, S.D., where he could start his life anew. “I had to go to a place where I could change my environment, my associates, and everything else,” he told William Rhoden of the New York Times. In Sioux Falls, he became counsel for an auditing firm and also started working as a drug counselor. All the while, he continued his battle against leukemia, remaining as active as possible in his professional life while frequently attending Mets reunions.

In the late 1990s, I had the chance to interview Clendenon while we co-hosted a show on MLB Radio. While I hardly can say that I knew him well, he could not have been more friendly or cordial during our brief exchange on the air. He came across as a true gentleman. Sadly, it was just a few years later that the bad news made its rounds. It was on Sept. 17, 2005, 20 years after his initial diagnosis, that Clendenon died from leukemia. He was 70 years old. Even though I talked to him only once, I consider myself lucky to have had that chance. Clearly, Clendenon was a man of character and morals, of intelligence and accomplishment. Yes, he made some mistakes along the way, but on balance, he lived a good and productive life. From a baseball perspective, it’s too bad that Clendenon didn’t live to see the 50th anniversary celebration of those ’69 Mets. Even in his absence, his impact remains strong. Mets fans who lived through 1969 will certainly remember the good man who helped bring the franchise its first championship.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame