- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1970 Topps Diego Seguí

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Diego Seguí

He was present at the birth of two Seattle baseball franchises, leaving his imprint on baseball in the Northwest for all-time.

Before and after, Diego Seguí proved to be one of the toughest pitchers of his era.

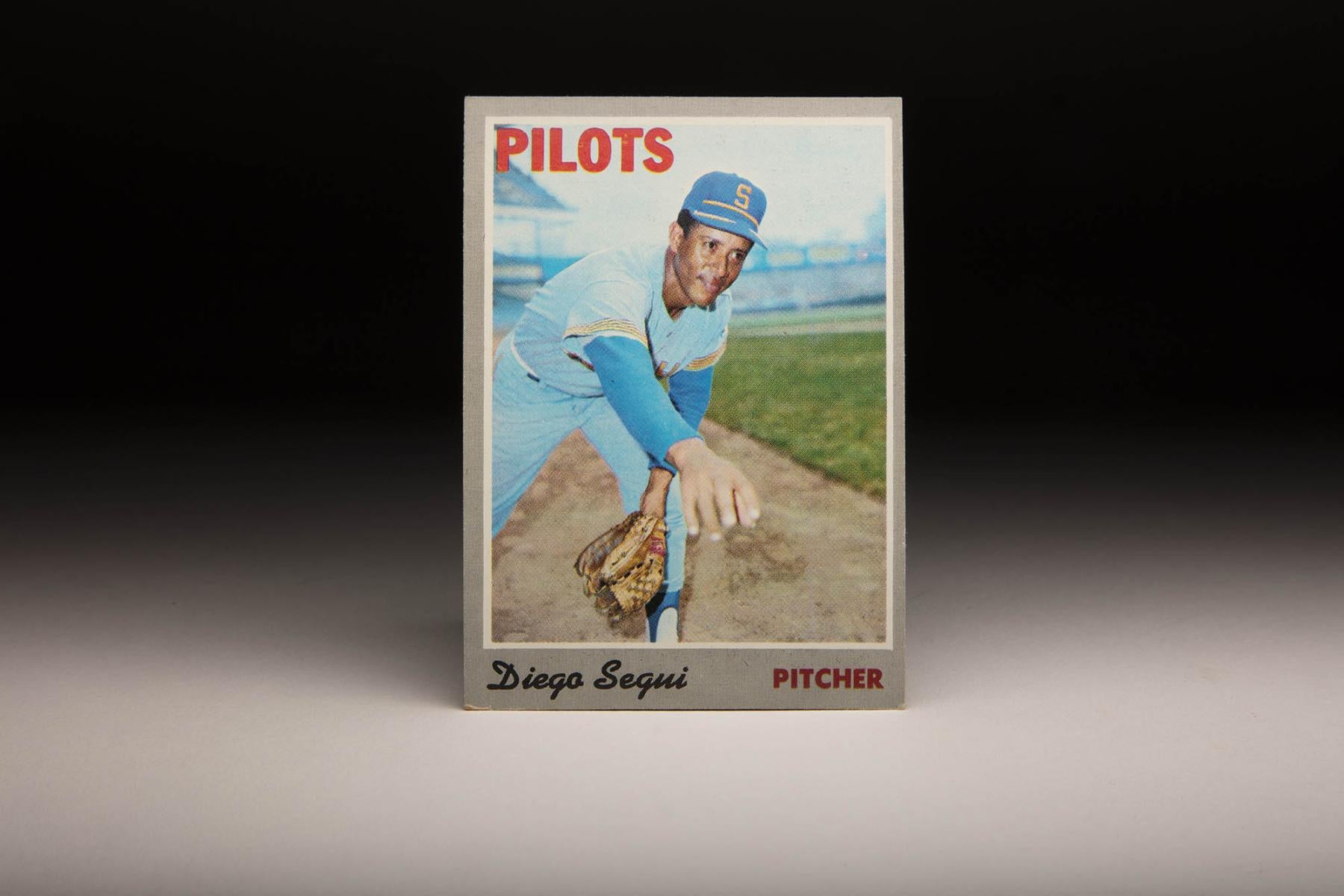

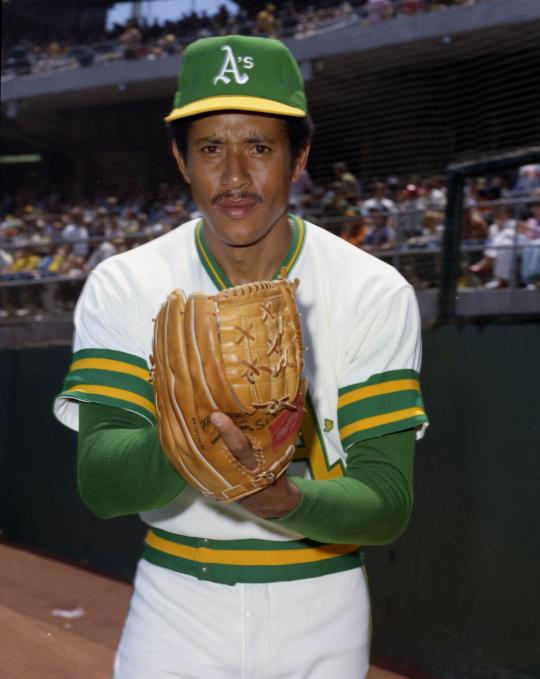

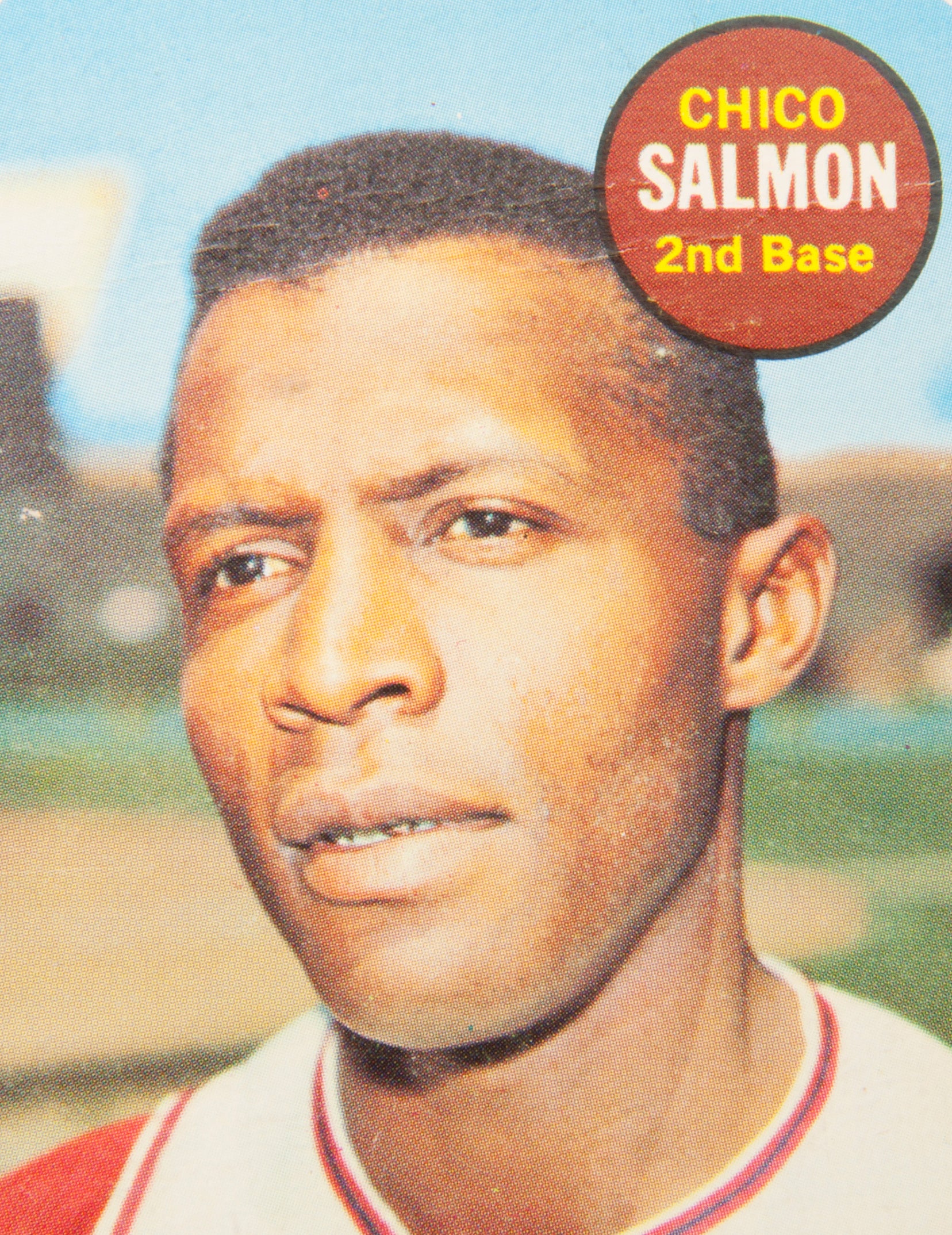

Seguí’s 1970 card features the out-of-the-ordinary look Topps brought forward for the new decade. After several sets in a row with small or no borders and only basic graphics, the 1970 offerings featured the distinctive gray background, script lettering for the player name and a bold team nickname.

All of these features framed Seguí’s image, which featured the 1969 uniforms of the one-and-done Seattle Pilots.

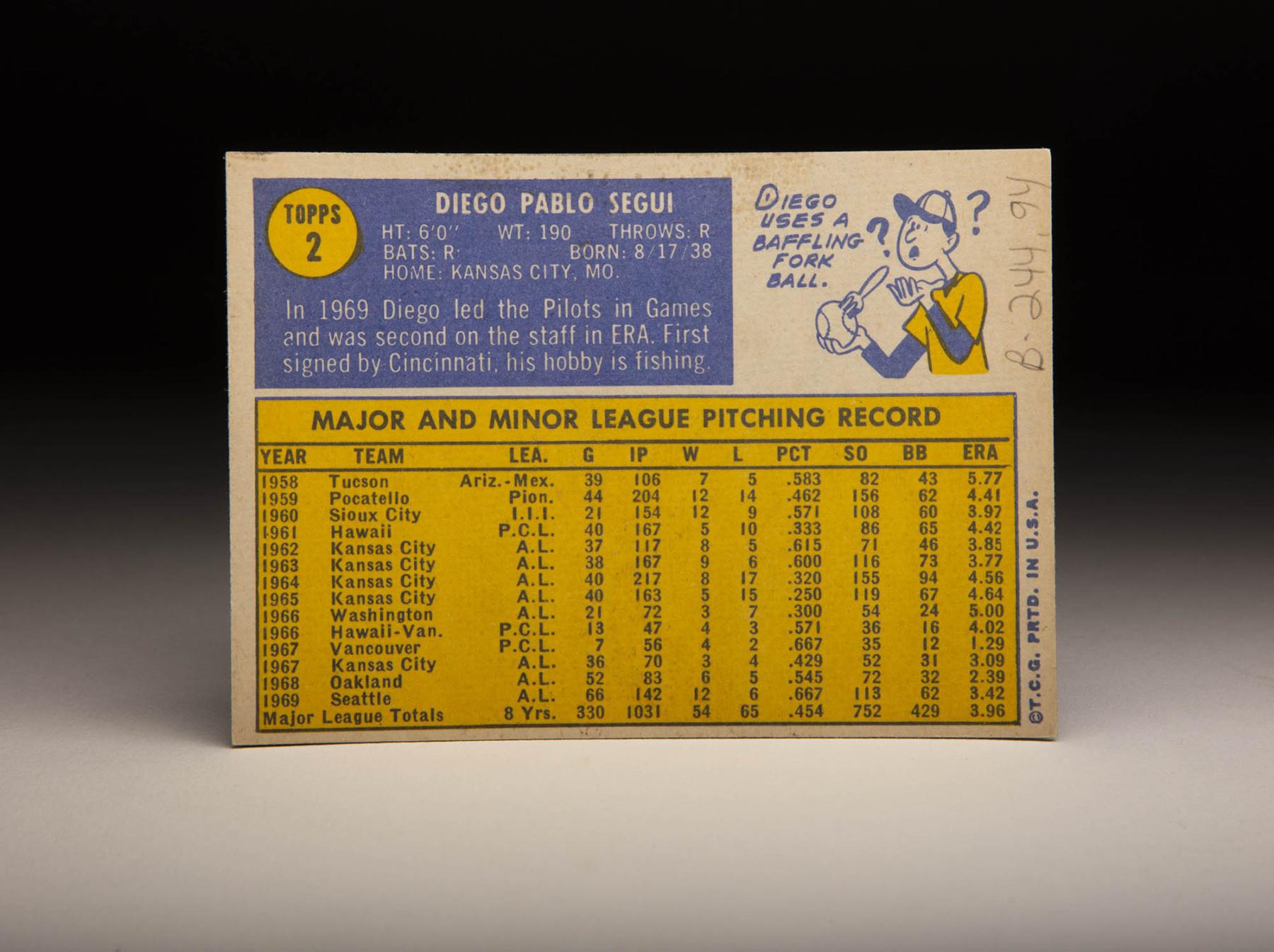

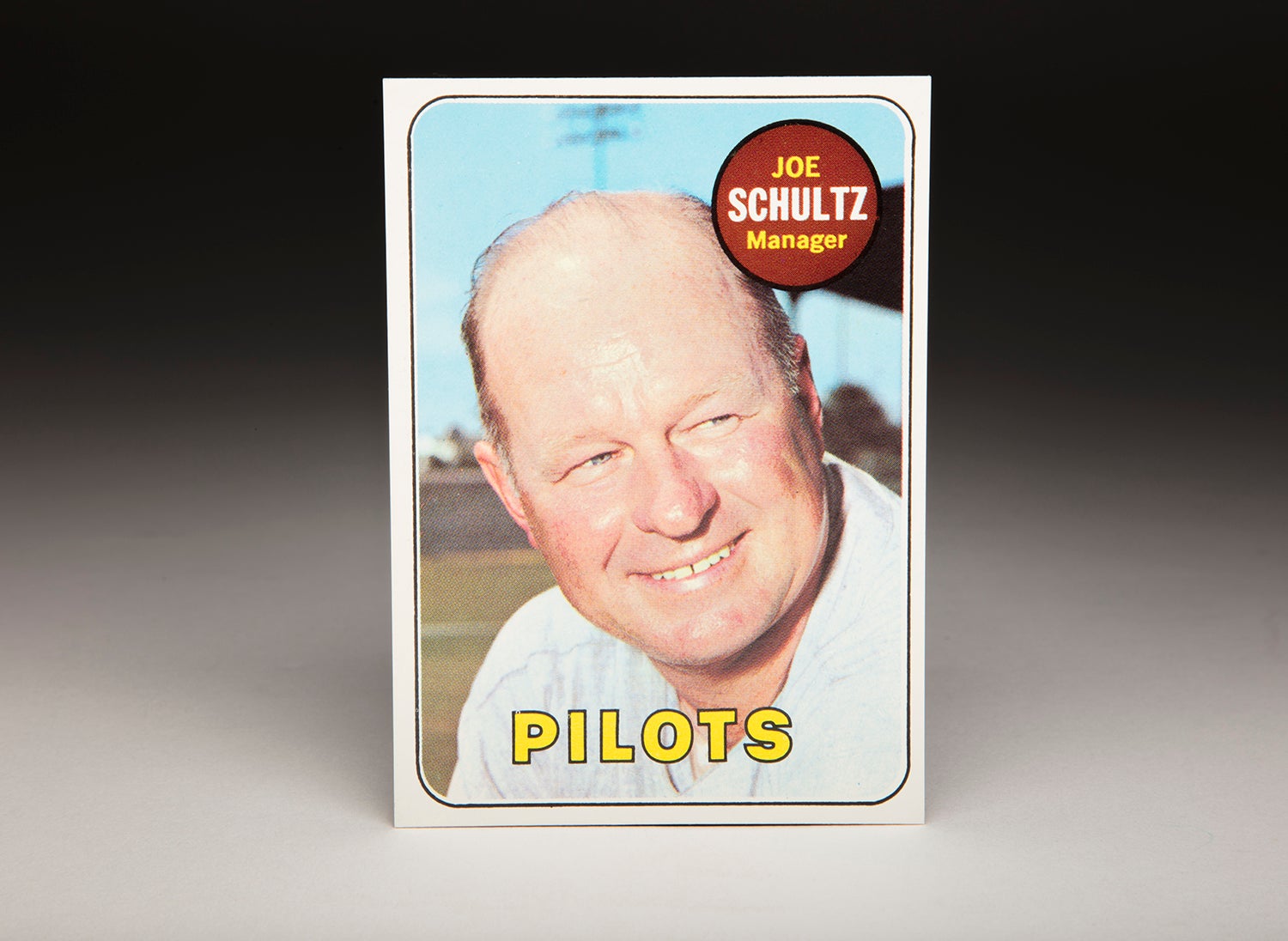

A seven-year big league veteran heading into the 1969 season, Seguí was the most effective pitcher on a Pilots team that won just 64 games and was made infamous by two events in the next decade: A bankruptcy that resulted in their move to Milwaukee just days before the start of the 1970 season; and the publication later that same year of “Ball Four”, Jim Bouton’s account of his time with the Pilots and Astros during the 1969 season.

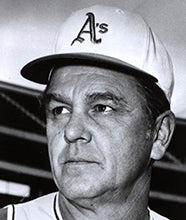

But while Bouton struggled to a 3.91 earned-run average with the Pilots, Seguí turned into one of manager Joe Schultz’s most trusted relievers. Seguí went 12-6 with a 3.35 ERA in 66 games, making eight starts and posting 12 saves in 142.1 innings. It was the most wins Seguí ever recorded in one season during his 15-year big league odyssey.

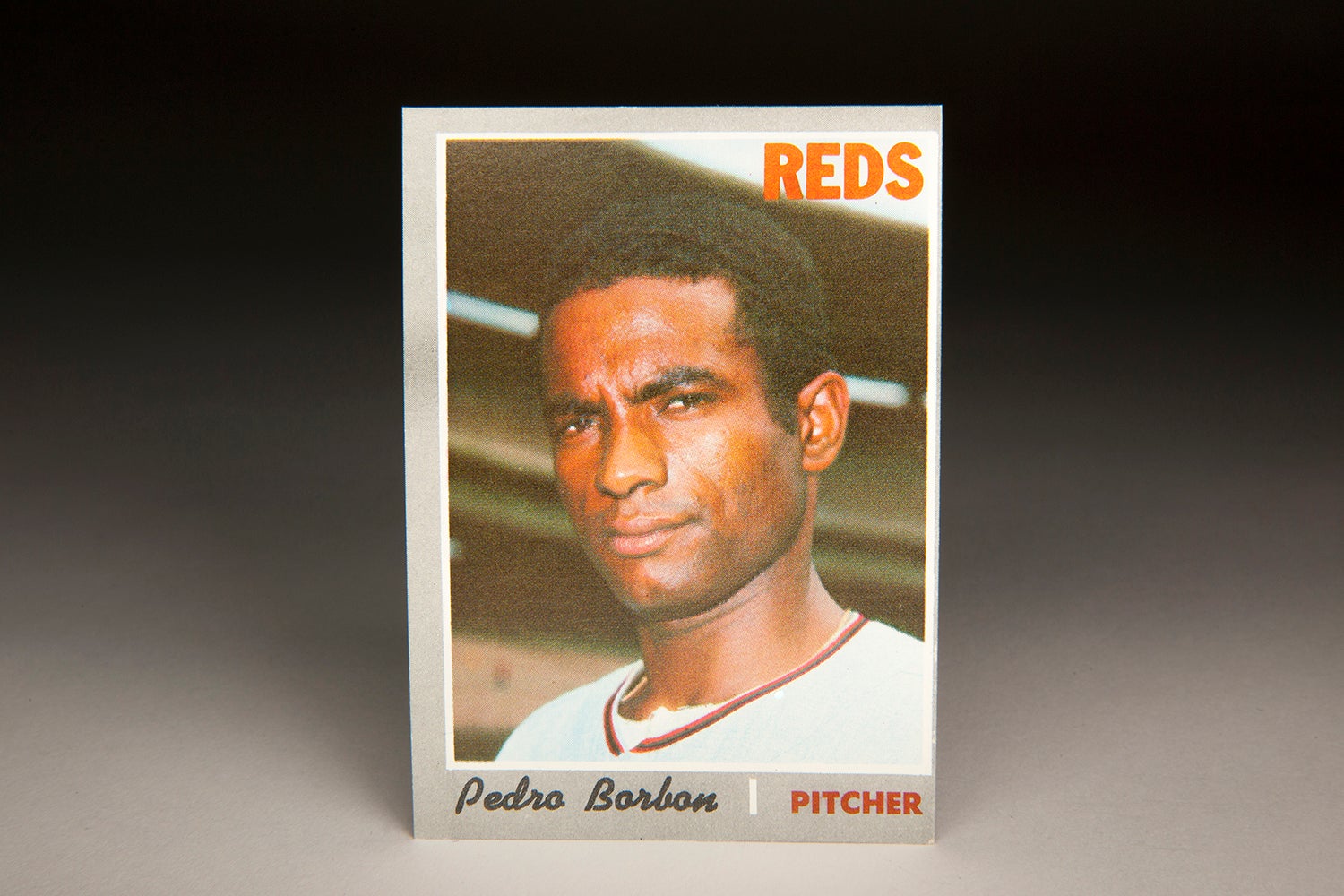

Born Aug. 17, 1939, in Cuba, Seguí was raised on a farm and had aspirations of becoming a big league hitter. But his strong right arm put him on the path to the pitcher’s mound, and he was signed to the Reds by legendary scout Al Zarilla prior to the 1958 season.

Before the end of April, the Reds released Seguí – and he spent the season pitching for Tucson of the unaffiliated Arizona-Mexico League. Toward the end of the 1958 campaign, his contract was purchased by the Kansas City Athletics, and he spent the next three seasons toiling in the A’s minor league system.

Following the Cuban revolution, Seguí chose not to return to his homeland – pursuing his dream of pitching in the majors and virtually abandoning any chance of returning to Cuba.

Seguí made the Athletics’ Opening Day roster in 1962, going 8-5 with a 3.86 ERA in 116.2 innings as a swingman. He received regular work as a starting pitcher the next three seasons before the Athletics – who averaged almost 97 losses per season in Seguí’s four years with the team – sold his contract to the Senators a few days after Opening Day in 1966.

He was traded back to the A’s on July 30, 1966, but did not pitch a game for Kansas City that year.

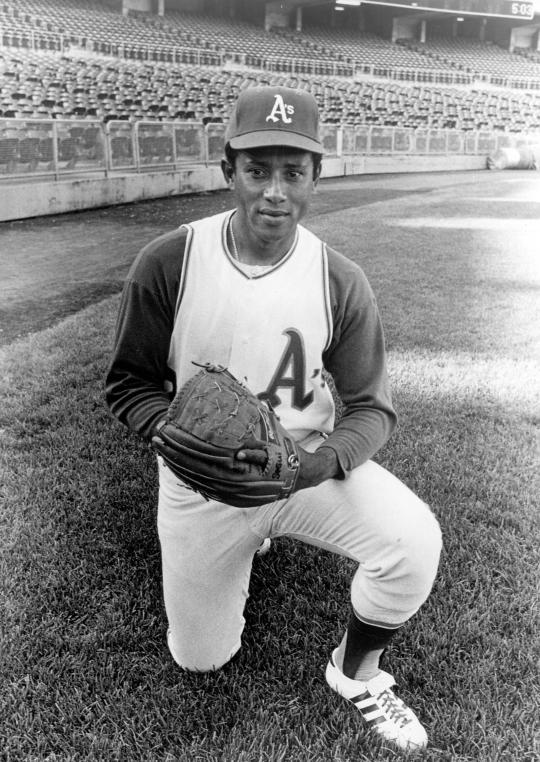

The next season, Seguí pitched to a 3.09 ERA in 36 games as a spot starter, then followed that up with his best season to date when the A’s moved to Oakland in 1968 – going 6-5 with six saves and a 2.39 ERA in 52 games.

But the A’s left Seguí unprotected in that fall’s Expansion Draft, and the Pilots grabbed at the chance to bring him to Seattle.

On Dec. 7, 1969, however, the Pilots traded their 1969 team Most Valuable Player back to the A’s in a deal with Ray Oyler in exchange for Ted Kubiak and George Lauzerique.

By this time, the A’s had stocked their team with young talent – and Seguí helped them win 89 games, the most by the franchise since the 1932 season when it was located in Philadelphia.

Seguí led the AL that year in earned-run average with a 2.56 mark, going 10-10 while qualifying for the ERA crown with exactly the 162 innings needed.

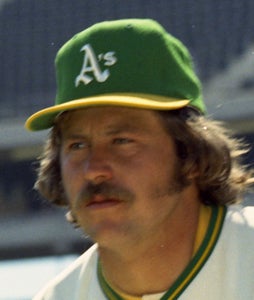

In 1971, Seguí was used mainly as a starter, and he went 10-8 with a 3.14 ERA for new manager Dick Williams. Oakland won 101 games that season on the strength of a monster year by Vida Blue, but injuries depleted the Athletics’ rotation late in the year.

The AL West champions lost Games 1 and 2 of the ALCS to the Orioles with Blue and Catfish Hunter on the mound, leaving Seguí as Williams’ best option to start Game 3. Seguí allowed three runs in 4.2 innings against Baltimore in a 5-3 loss, but Williams praised Seguí’s willingness to take the ball and battle in an elimination game against the defending World Series champions.

But Seguí would not be around to experience the A’s three straight world championships in the ensuing seasons. A’s owner Charlie Finley traded Seguí to the Cardinals on June 7, 1972, and Seguí pitched effectively for the next two years – going 7-6 with 17 saves with a 2.78 ERA over 65 games in 1973.

The Red Sox acquired Seguí following the 1973 season, and he was a bullpen mainstay for Boston over the next two seasons – helping the Sox reach the 1975 World Series and even appearing in the Fall Classic in Game 5 at the age of 38, working one inning of relief.

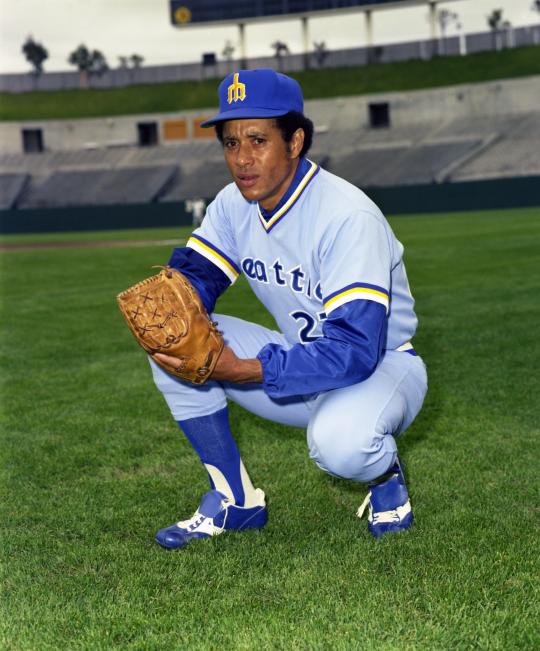

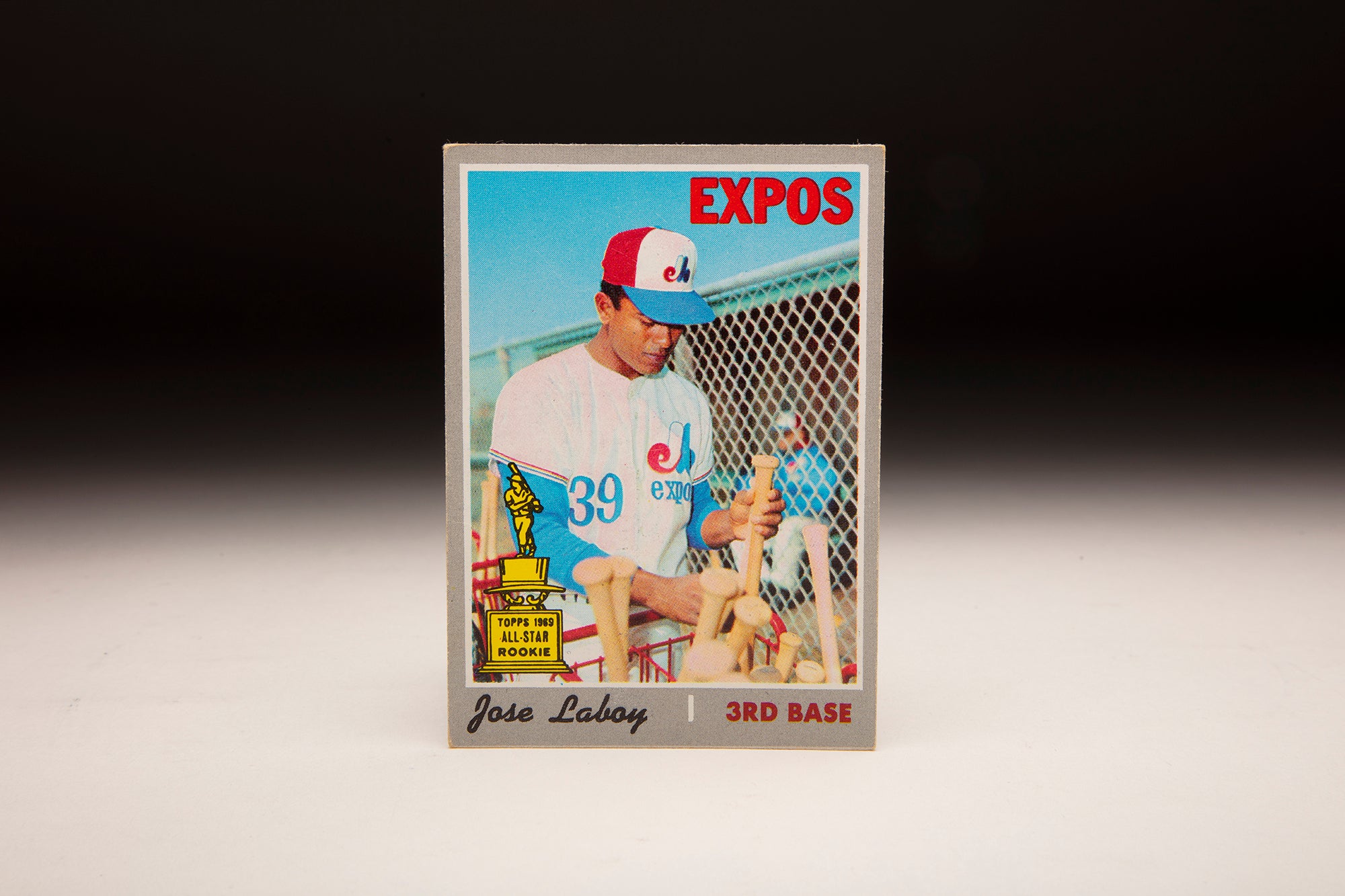

The Red Sox released Seguí on the eve of the 1976 season, and after pitching that season with Triple-A Hawaii, the Islanders’ parent club – the Padres – sold Seguí’s contract to the expansion Seattle Mariners.

In front of 57,762 fans at the Kingdome on April 6, 1977, Seguí threw the first official pitch in Mariners’ history – taking the loss in Seattle’s 7-0 defeat at the hands of the Angels. After going 0-7 with a 5.69 ERA in 40 games for Seattle that year, Seguí’s big league career came to an end.

Known for a variety of off-speed pitches and a deliberate manner on the mound, Seguí finished with a record of 92-111 with 71 saves and a 3.81 ERA. His son David carried on the family tradition in the big leagues, playing 15 seasons from 1990-2004.

Seguí passed away on June 24, 2025, at the age of 87. Forever the answer to a trivia question, the only man ever to play for both the Pilots and the Mariners left a legacy worth remembering.

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum