- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1970 Topps Jose ‘Coco’ Laboy

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Jose ‘Coco’ Laboy

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

During the creation of our new baseball card exhibit, the eye-catching Shoebox Treasures, the Hall of Fame and Museum received a number of donations of cards from enthusiastic fans.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

One of the most generous donations came from a gentleman in Texas who supplied us with thousands of card, including what appears to be a complete set of 1970 Topps. The collection of 1970 cards includes numerous Hall of Famers, along with rookie cards, common cards, team leader cards, and World Series cards.

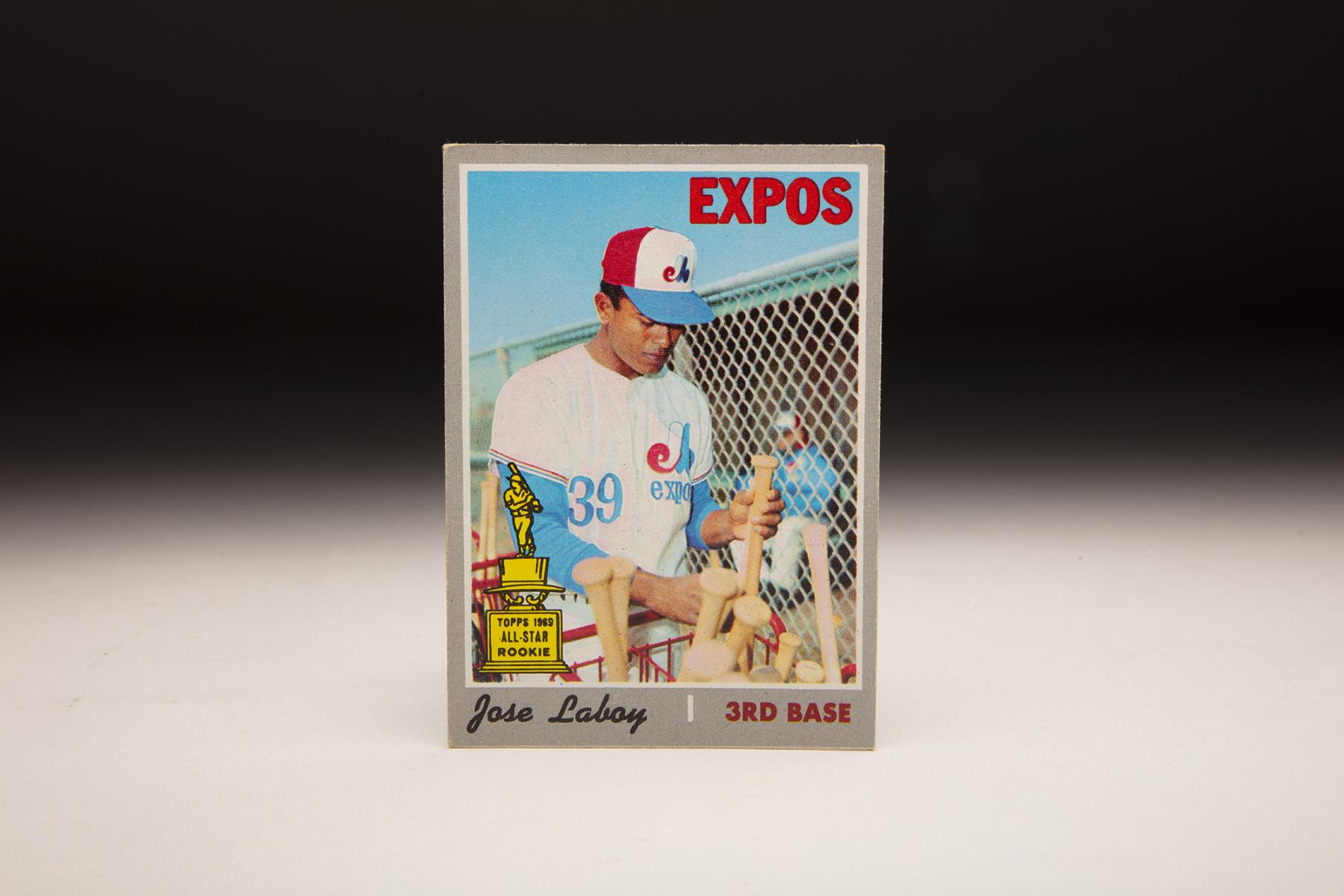

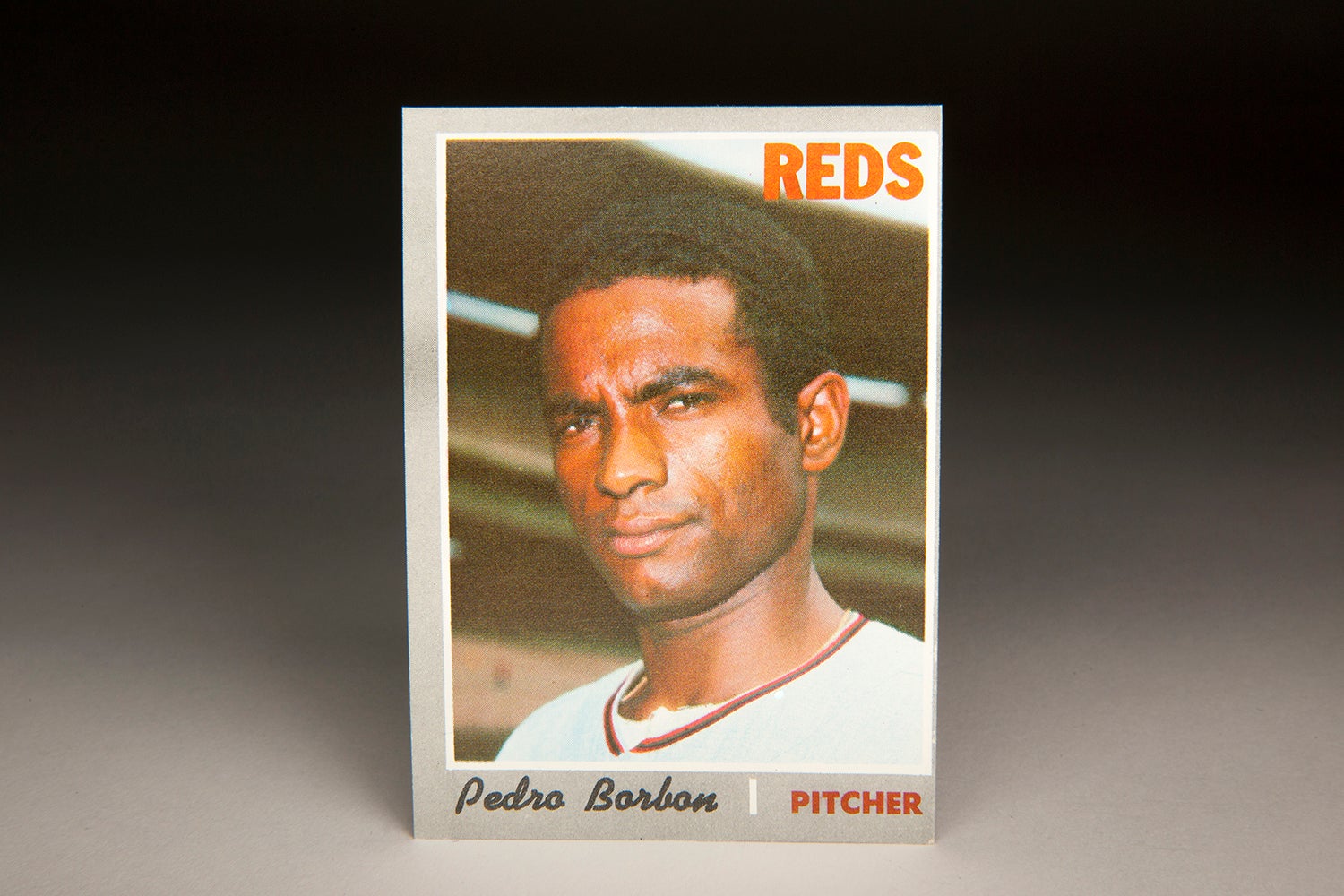

In looking through the large smattering of 1970 Topps, I was struck by the understated quality of this set, which has generally been overlooked and unheralded. The cards have a clean look and a simple design, accented by the subtle gray borders, the player’s name spelled out in script and his position listing at the bottom of the card, and the team name in bold capital letters at the top of the card.

The quality of the photographs found in 1970 Topps is also pretty good. Some of the photos are blurred, but all of the photos in the set came from fresh sources. In the 1968 and ’69 sets, Topps had to rely on recycling many old images and using a heavy dose of airbrushing in response to the players’ refusal to pose for new photographs, all part of a longstanding dispute between the card company and the Players’ Association. By the time that Topps started production on its 1970 set, that labor disputed had ended, freeing up the players to pose for new photographs.

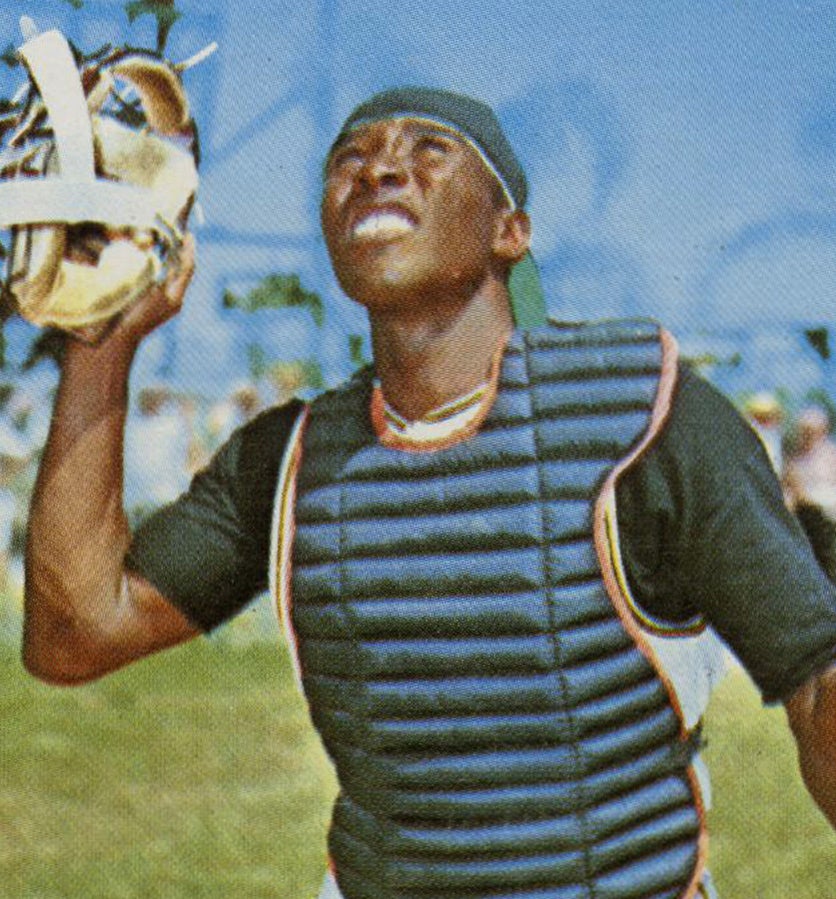

At the same time, Topps started to become a bit more creative in its approach to photography. Action shots were still one year away from reality (in the form of the groundbreaking 1971 set), but Topps found a way to add variety to the usual staged poses of position players holding bats and pitchers feigning their throwing motions. The ’70 set features a number of what could be called “candid shots,” which show players doing routine activities while seemingly oblivious to the camera.

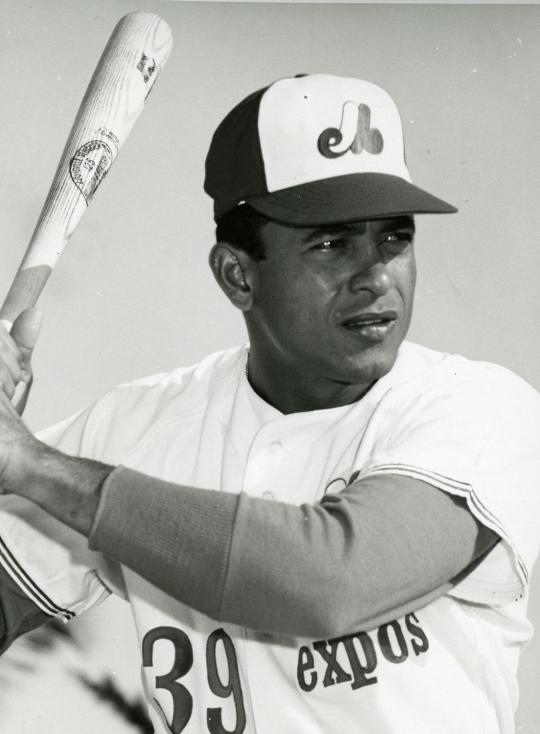

In the ’70 set, we see some players signing autographs for fans (like New York’s Bud Harrelson), relaxing near the batting cage (Oakland’s Dave Duncan) and making selections from the bat rack (Baltimore’s Andy Etchebarren and Kansas City’s Bob Oliver). From the latter category, one of the better selections shows us Montreal Expos third baseman Jose Laboy, his head turned downward, while he gives serious thought to what bat he will use during batting practice. With his left hand, Laboy grasps what appears to be the winning bat, in much the way that the New York Knights batboy selected a “winner” for Robert Redford’s Roy Hobbs in the wonderful 1984 film, The Natural.

Of course, all of this was probably staged by the Topps photographer, who likely instructed Laboy to pretend picking a bat from the bin near the dugout. But at least the scene looks natural, or candid, so to speak. At the very least, it gives us something different from the usual posed photographs, where the player looks awkward as he stares stiffly into the camera.

There is more of interest to be found in the Laboy card. The photograph appears to have been taken during the expansion Expos’ first-ever Spring Training, which took place in West Palm Beach, Fla., in February and March of 1969. The dugout, if that’s what this structure actually is, appears to be the kind that would be found at a high school ballfield. The wire fencing gives it an appearance of a large cage. With the fencing running from the ground to the top of the dugout, it is not a particularly attractive look for a professional dugout; but then again, it provides considerable protection for players and coaches from foul balls, which has become an ongoing topic of discussion with regard to fan safety in 2019.

The card also features that gaudy image of Topps’ All-Star Rookie Trophy, presented in a full-blown yellow cartoon depiction that makes it leap from the card. In reality, the Topps trophy is not a bright yellow, but has a bronze-looking finish, as evidenced by the Johnny Bench trophy that is currently featured in Shoebox Treasures.

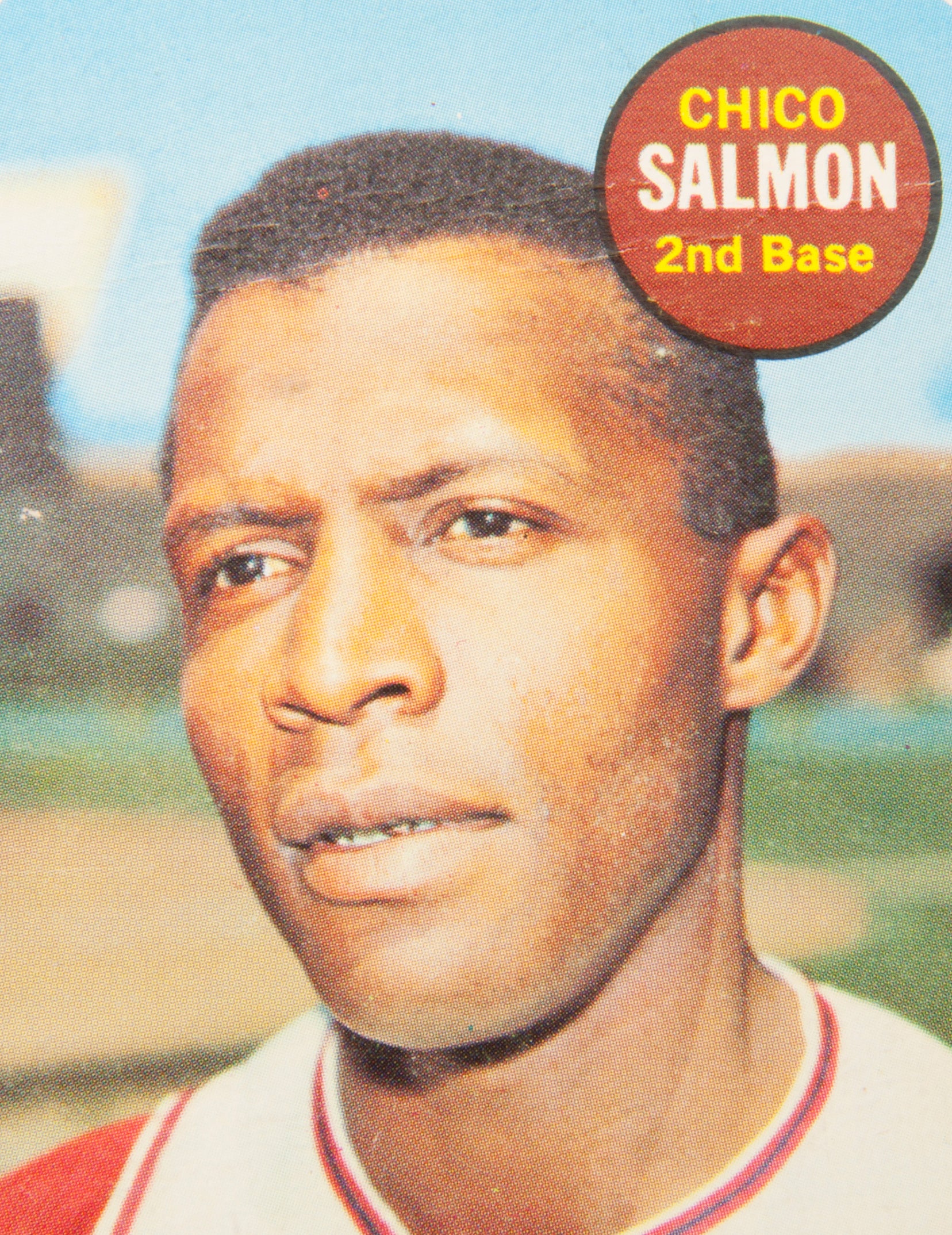

There’s one other item of intrigue from the card. On the face of the card, Topps lists the Expos’ third baseman as “Jose” Laboy, as the company also did on his cards in 1972, ’72, and ’73. But any fan who was alive and following the game in the late 1960s or early 70s remembers this player as “Coco” Laboy.

It was a lyrical name, one that broadcasters loved enunciating and one that young fans like myself reveled in repeating over and over. “Coco Laboy!” we shouted whenever we came across one of his Topps cards.

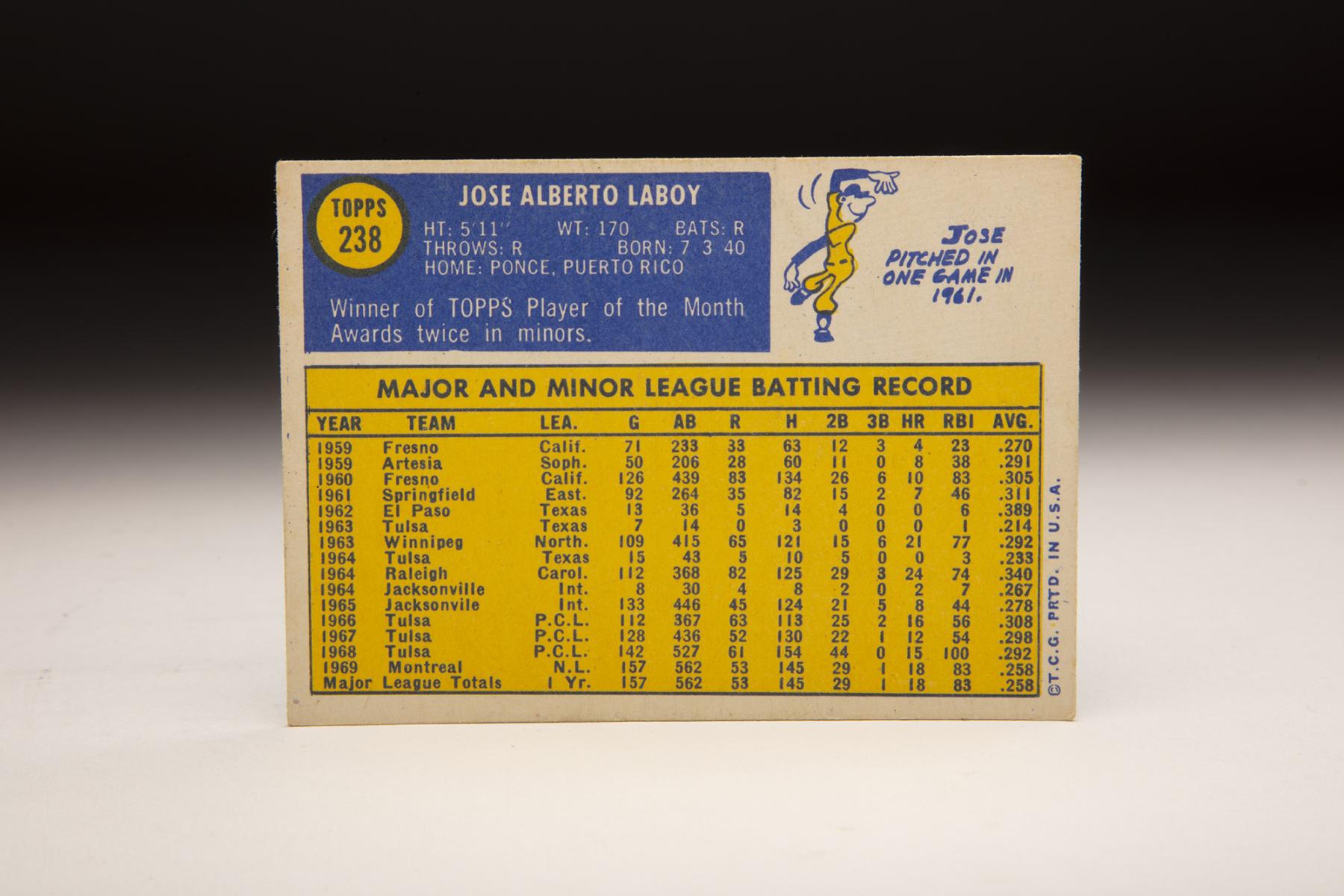

Although Laboy was officially regarded as a rookie in 1969, he was already 29 years old. The start of his professional career dated back a full decade, all the way to 1959. That’s the year that several San Francisco Giants scouts, including Hall of Famer Alex Pompez, watched Laboy in his native Puerto Rico and recommended that the organization sign him. Trusting the reports from Pompez and fellow Giants scout Pedro Zorrilla, the Giants signed the 18-year-old.

Laboy split his first season between the Class D Sophomore League and the Class C California League. The Giants played him primarily at shortstop, but also used him at third base and in the outfield. At the plate, he put up solid numbers. The following season, the Giants kept Laboy at Class C Fresno for the entire summer, but switched him to second base. He responded well, showing good range at second base while hitting .305 with 10 home runs and 74 walks.

In 1961, the Giants bumped him up to Class A Springfield of the Eastern League, where he improved his average even more, hitting .311 and helping Springfield win the league championship. Another promotion came his way in 1962, this time to the Double-A Texas League. Laboy hit well in the early season, but suffered a back injury. He tried to return, only to incur a relapse that sidelined him for the rest of the year. As a result, he played in only 13 games, amounting to a nearly wasted season.

At the end of the season, a doctor examined Laboy’s back and gave him a grim prognosis.

“The doctors told me I’d never play again,” Laboy bluntly told the Sporting News. Heeding the doctor’s words, the Giants released Laboy, but he would not give up the dream of playing the game professionally. Instead, he signed a minor league contract with the St. Louis Cardinals, who assigned him to their Double-A affiliate at Tulsa.

A shaky start to the season resulted in a demotion to Winnipeg of the Northern League. Proving his doctor wrong, Laboy excelled for Winnipeg, while showing newfound power. He hit 21 home runs and slugged .508. His back held up as he played three different positions: second base, third base, and the outfield.

Laboy felt so good that he again played Winter League ball – which he did annually – before reporting to the Cardinals’ Spring Training camp in 1964. Again assigned to Class A ball, he emerged as a Carolina League All-Star. But then came an interruption to his season.

In a late August game, Laboy felt he was being thrown at intentionally by a pitcher for Rocky Mount. In the fifth inning, Laboy laid a bunt down the first base line, forcing the Rocky Mount pitcher to field the ball. Rather than run directly toward first base, Laboy went for the pitcher, his bat still in hand. He swung the bat at the pitcher, triggering an all-out brawl that lasted for 15 minutes. It was an uncharacteristic moment for Laboy, who was generally regarded as an even-tempered player and a gentlemanly sort by his teammates.

Not only was Laboy ejected from the game, but he was charged with a crime by local police: Assault with a deadly weapon. After pleading guilty, he was sentenced to 30 days in jail, but the sentence was suspended in lieu of a fine. The Carolina League, however, did not let Laboy off so easily. The league president suspended Laboy, who was leading the league in batting average at the time, for three games.

While the Cardinals were upset by Laboy’s involvement in the bat-swinging incident, they still regarded him as a prospect. Later that season, the front office promoted him all the way to Triple-A Jacksonville, where he helped his new team clinch the International League pennant. That winter, the Cardinals added Laboy to their 40-man roster and brought him to Spring Training with a chance to make the team.

While Laboy’s athleticism and versatility intrigued the Cardinals, he was also facing a few obstacles, notably the presence of veteran third baseman Ken Boyer and two other versatile infielders in Phil Gagliano and Jerry Buchek. Beating out Laboy, Gagliano and Buchek won spots on the Opening Day roster. That meant that Laboy would have to head back to Triple-A. Playing his first full season at that level, Laboy batted .278 with only eight home runs.

After the 1965 season, the Cardinals traded Boyer to the New York Mets for left-hander Al Jackson and a younger third baseman in Charley Smith. In the spring of ’66, the Cardinals held an open competition for the third base job, and Smith won out. Once again, Laboy returned to Triple-A. For the next three seasons, Laboy remained a fixture with the Tulsa Oilers, first stuck behind Smith, and then behind Mike Shannon, whom the Cardinals converted from the outfield to third base in 1967.

For those three seasons in Tulsa, Laboy excelled at third base, culminating in a 1968 season in which he batted .292 with 15 home runs and 100 RBI. With Shannon coming off a solid season in 1968, there was simply nowhere for Laboy to play in St. Louis. That winter, the Cardinals left him unprotected in the expansion draft. With the 54th pick of the draft, the Expos selected Laboy, based largely on a recommendation from Philadelphia Phillies infielder Tony Taylor, who had played with Laboy in Winter League ball. Taylor told Gene Mauch, formerly his manager in Philadelphia and now the manager of the Expos, that Laboy was a good, smart player.

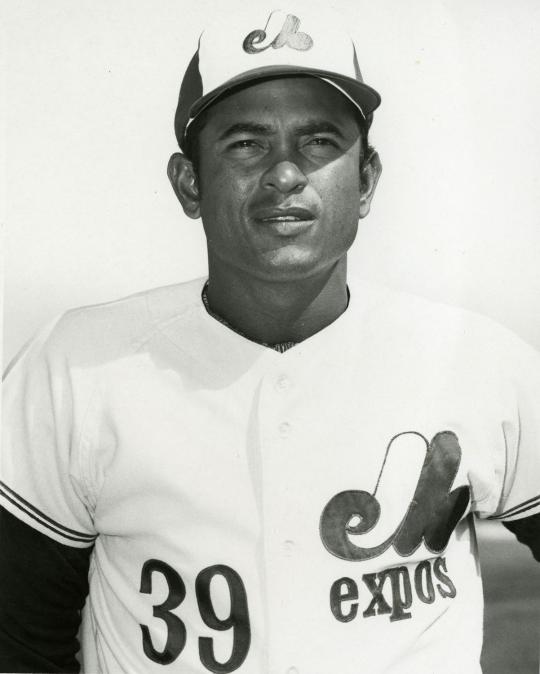

The 28-year-old rookie played well that spring, impressing Mauch and winning the battle to start at third base. After 10 seasons of minor league travails, the 28-year-old made his major league debut in 1969. He took full advantage of the opportunity. He started the season by hitting at a .420 clip, the highest average in either league. Inevitably, he would cool down, but remained a significant contributor. Playing in 157 games for Mauch, Laboy’s average settled at .258, but he clubbed 18 home runs and played a terrific third base. National League writers took note, voting him second to Ted Sizemore in the league’s Rookie of the Year balloting. For his part, Mauch praised Laboy for his character and professionalism.

Laboy’s arrival in the big leagues also brought attention to his nickname, Coco. According to an article that appeared in the Sporting News, Laboy used to enjoy eating chocolate bars (made from cocoa beans) before making the transition to smoking cigars. But many years later, after Laboy retired from baseball, he claimed that story to be untrue. He said his mother had given him the nickname for a reason unknown to him. He simply accepted the memorable moniker.

Laboy’s nickname would continue to receive attention in 1970, but his on-the-field play would suffer. Facing Laboy the second time around, National League pitchers threw him fewer fastballs and relied more on breaking balls. Laboy struggled against the new approach, his batting average falling to .199.

Determined to make a comeback in 1971, Laboy went home to play in the Puerto Rican Winter League, but suffered a major knee injury. The knee would continue to bother him throughout the ’71 season, limiting him to 76 games.

Laboy hoped that the pain in his knee would subside, but it remained problematic when he reported to Spring Training in 1972. He underwent surgery in March, sidelining him until July of that season.

He then went back to the minor leagues for a spell, returned to Montreal in September, and finished the season with a .261 average, but without much power.

In 1973, Laboy opened the season as Montreal’s third baseman, but endured a dreadful start. With his batting average at .121, the Expos assigned him to their minor league affiliate in Quebec. At the end of the minor league season, the Expos released Laboy, ending his major league career.

Many years later, Expos president John McHale lauded Laboy for his contributions. In an interview with longtime Expos beat writer Ian McDonald, McHale described Laboy as “a plus for the team on and off the field. He had a million-dollar name and the fans loved it.”

With his playing days over, Laboy took a government job in his native Puerto Rico, which led to him doing work with the country’s sports programs. He also managed for a few years in the Puerto Rican Winter League and did some scouting for the Seattle Mariners. In the latter position, Laboy scouted a young Puerto Rican third baseman named Edgar Martinez. Laboy’s reports on Martinez helped convince the Mariners that they should sign the Hall of Fame batsman.

As a major leaguer, Laboy’s career was brief, but it was memorable. My friends and I always enjoyed his lyrical name, as did most fans of that era. And even if the nickname of Coco somehow escaped mention on his Topps cards, his 1969 rookie card still makes for a fun topic of conversation.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame