- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Paul Casanova

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Paul Casanova

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

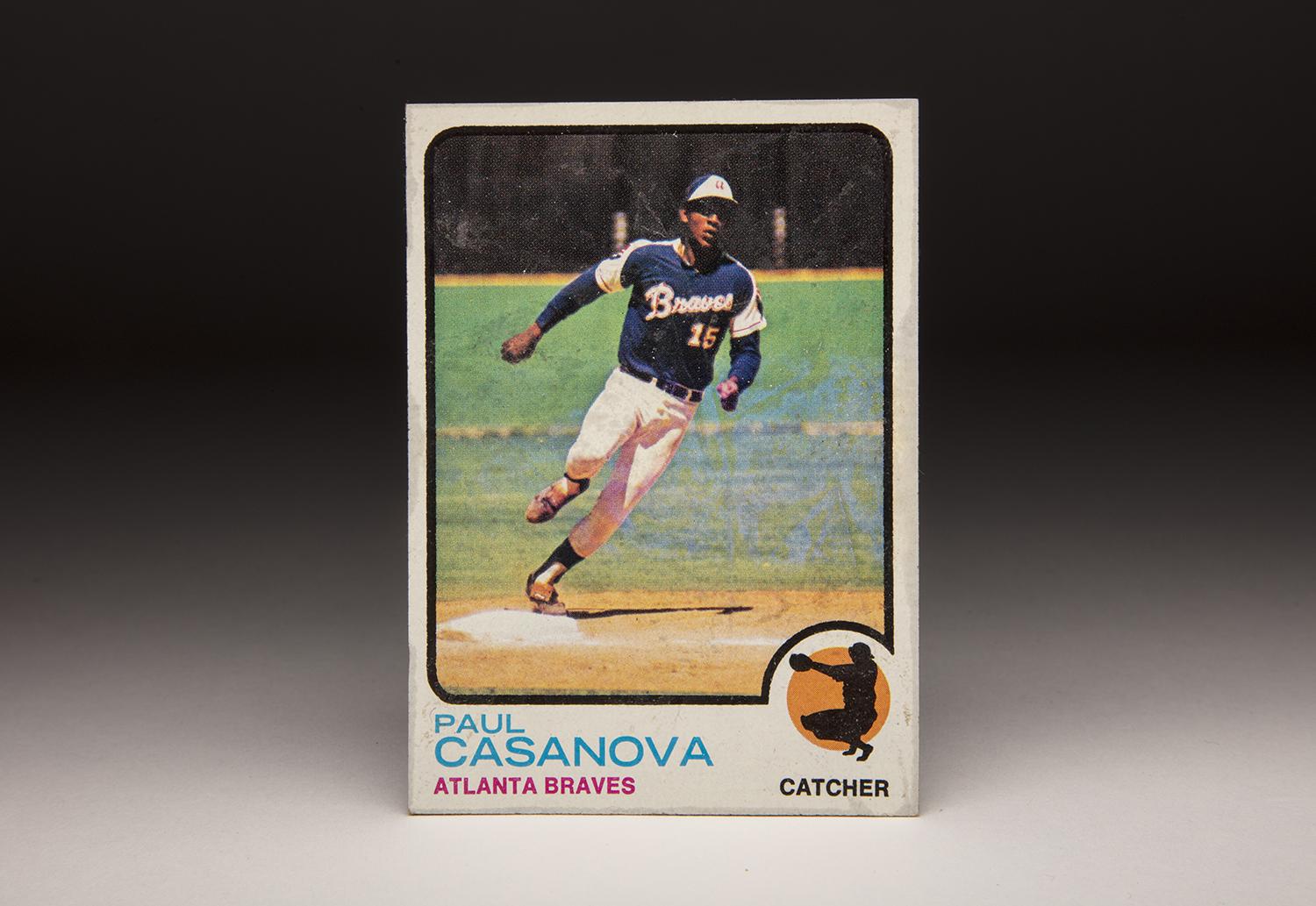

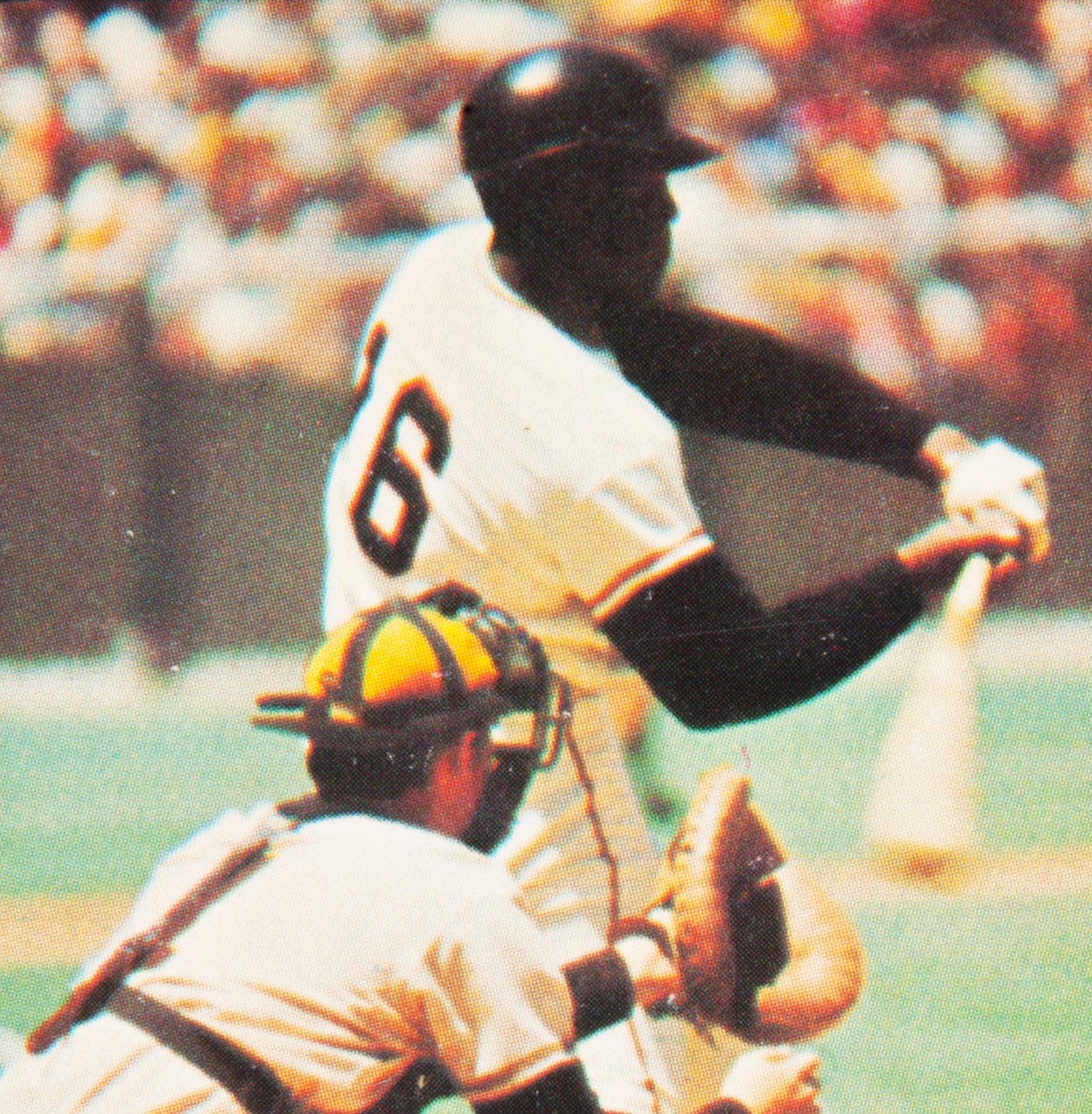

Can a baseball card teach us how to play the game? Probably not, but Paul Casanova’s 1973 Topps card comes as close as any I’ve seen.

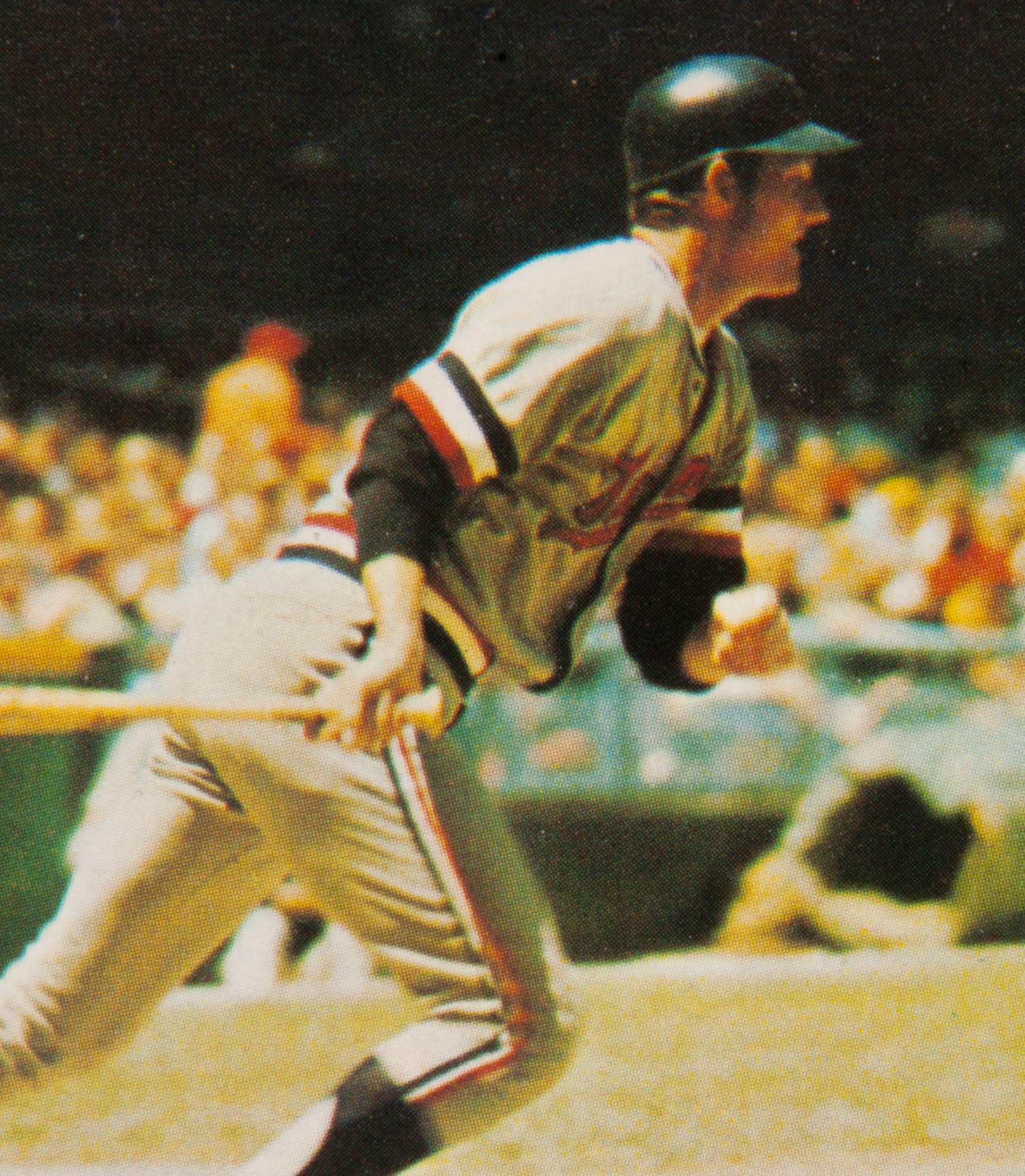

If you want to show a youngster a card that depicts good baserunning technique, start with the Casanova card. Notice how Casanova has his fists clenched and his arms extended, just the way that a baserunner should. Also, take a look at Casanova as he rounds the third base bag. His left foot is touching the inside corner of the third base bag, while his right leg looks it’s about to step over and beyond the bag. This is the way that a baserunner should cut the corner as he makes the turn at third base and heads for home.

There’s no way to tell how fast Casanova is running, but he at least looks to be running hard and running with proper form. Appearances can be deceiving, but Casanova has the look of a relatively fast baserunner. In examining the card, it’s hard to believe that he was a catcher. We tend to think of catchers as muscular and heavy, with squatty bodies build low to the ground. Not Casanova. He has the kind of long and lean body that we would normally associate with a fleet center fielder or an athletic shortstop.

While 1973 Topps has drawn some criticism for out-of-focus action shots taken from long distances, the Casanova card is one of the most beautiful in the set. There is no blurring here, and there is need to pull out a magnifying glass to determine if it is really Casanova. The layout is also good. The photographer has framed Casanova well, putting him squarely within the perimeters of his lens.

The card also shows off a nice contrast between the bold blue jersey that the Atlanta Braves wore in 1972 and the bright green artificial turf behind Casanova. This was the road uniform that the Braves wore in that time period, but it’s difficult to pin down the exact location. A number of National League teams used artificial turf in ’72, so this could be Candlestick Park in San Francisco, or Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia, or perhaps one of the other cookie cutter stadiums in vogue at the time.

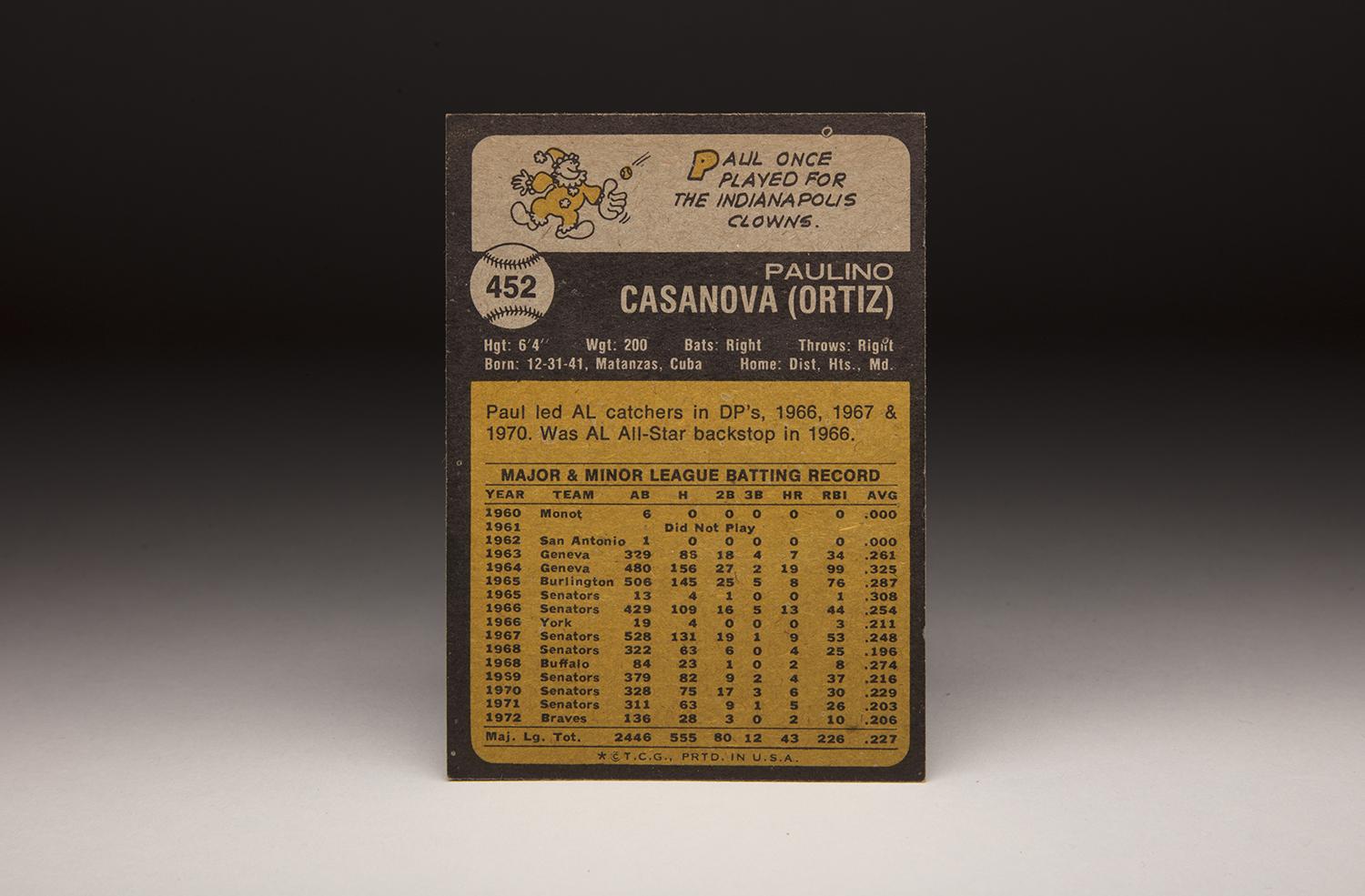

In an unrelated way, Casanova was a player who was somewhat mysterious to me while I was growing up in the early 1970s. First, I had no idea that Casanova was Latino. With a first name of Paul, I had always thought him to be born and bred in this country, and not in Cuba. I didn’t realize that his first name was actually Paulino. His last name also became a source of humor with young fans like me. “Casanova” is a word that I first heard in the movies, used to describe someone who might be termed a playboy. For that reason, we thought it was a funny last name.

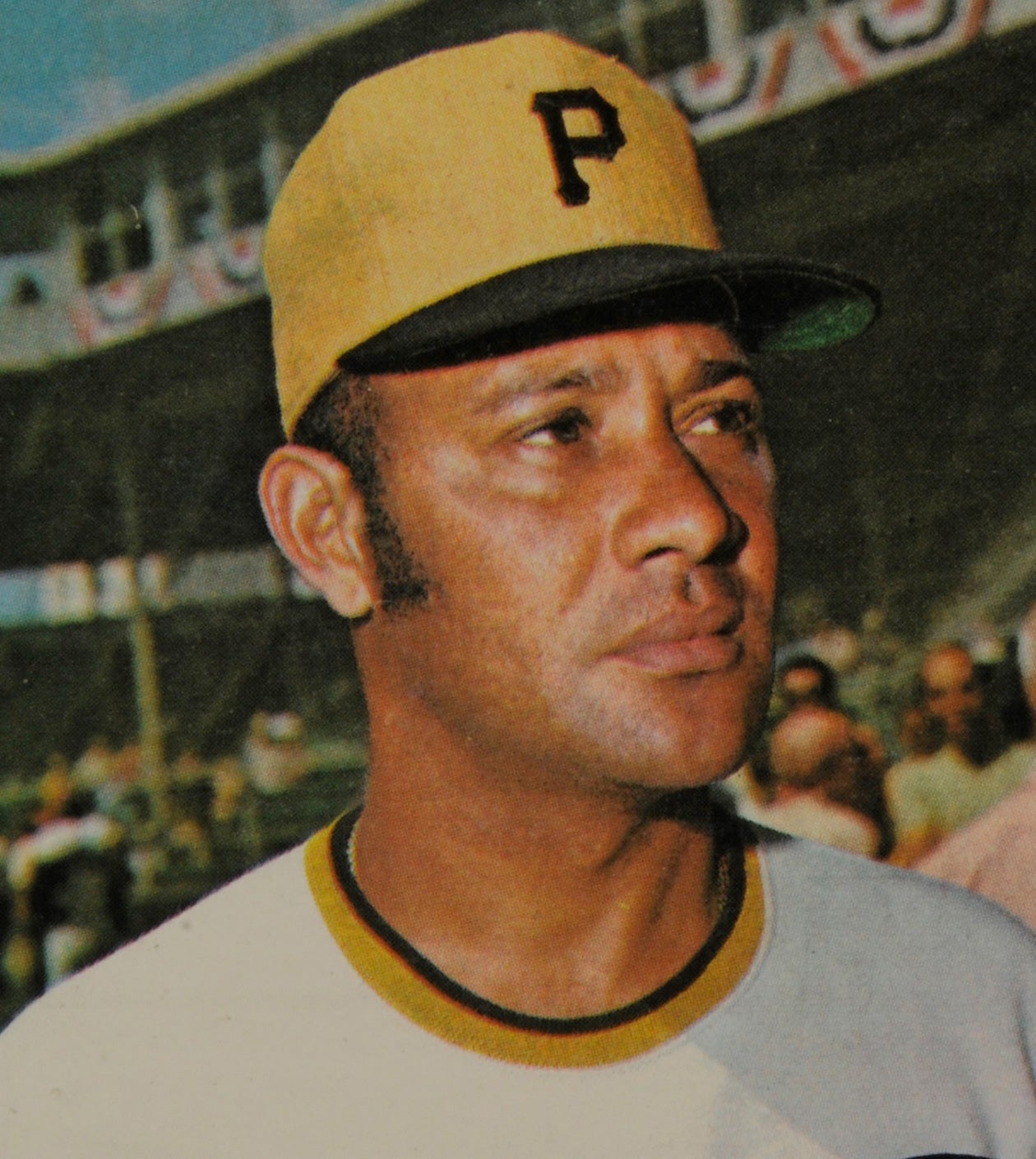

I had other misconceptions about Casanova. I did not know that he played in the Negro Leagues prior to beginning his major league career. Casanova was born in 1943, only four years before the debut of Jackie Robinson, so it seemed that the Negro Leagues would have been a thing of the past by the time Casanova came of age. But Casanova did play in the last remnants of the Negro Leagues, emerging as a standout for the Indianapolis Clowns in 1961. By the early 1960s, the Clowns were only a facsimile of their peak teams of the forties and fifties, but Casanova did play well for the all-black team.

Casanova grew up in a town called Colon. Coming from a family with little money to buy him equipment, Casanova improvised. He cut down a tree and fashioned his own home-made bat. From an early age, he wanted to catch, so he constructed his own catcher’s mask out of wire. Clearly, nothing would prevent Casanova from pursuing his dream of playing baseball.

The Cleveland Indians scouted Casanova while he played semi-professional ball in Cuba. Impressed by his defensive skills, and his commanding way of handling the catching position, the Indians offered him a contract in 1960. Casanova took the deal, but it didn’t give him the kind of opportunity he wanted. Assigned to the Northern League, Casanova spent most of his time as a bullpen catcher. He appeared in a handful of games, came to bat only six times, and drew his release. The Indians then re-signed him during the winter, but released him in April, before he could even come to bat. The Indians explained their handling of Casanova quite simply: They didn’t think he could hit enough to make the major leagues.

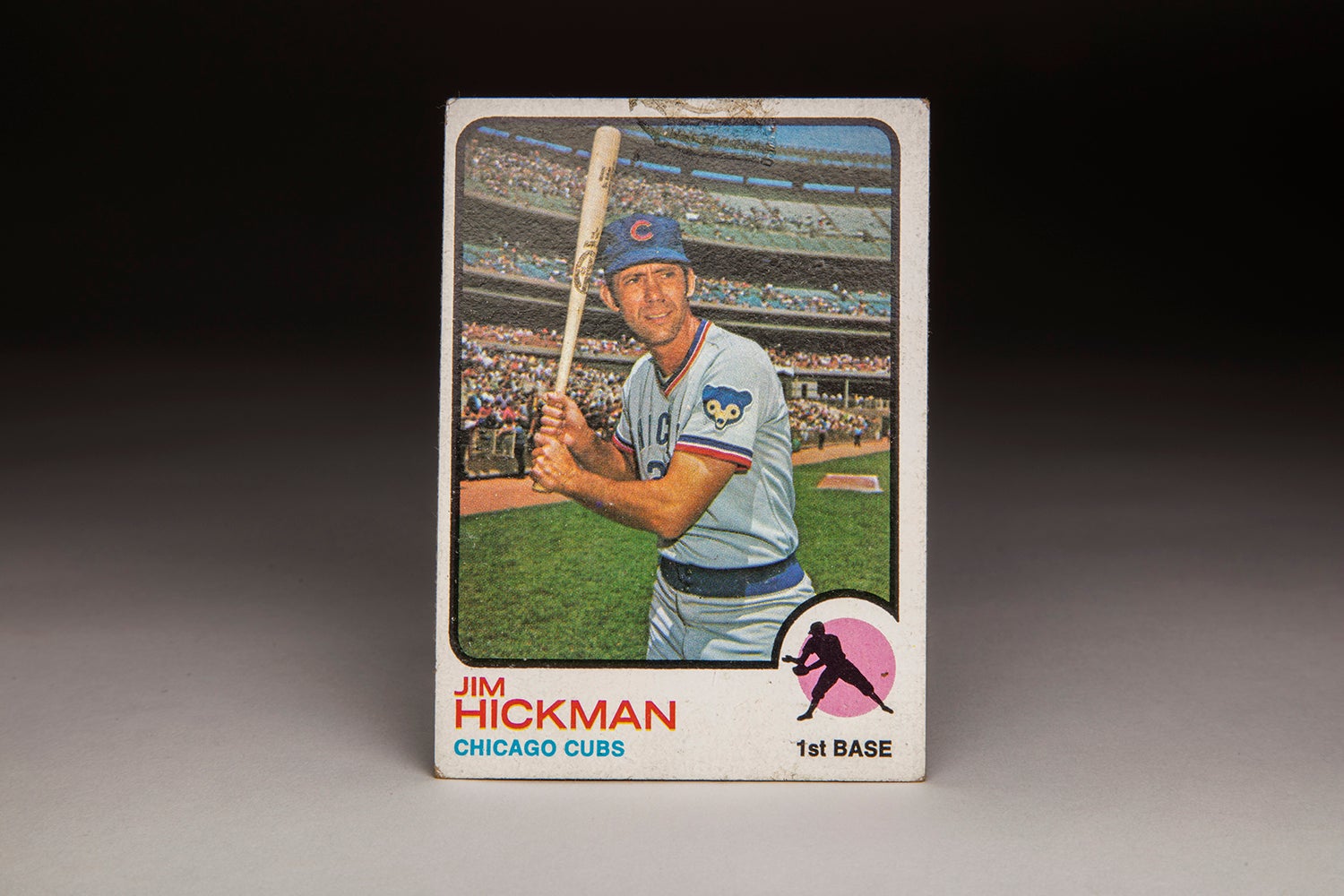

After the release by the Indians, no other major league team showed interest in Casanova. Not willing to concede his career, Casanova signed on with the Clowns, an independent all-black team that barnstormed across the country. As with many of the all-black teams, life with the Clowns was lacking in glamour. The team traveled by bus, which also served as sleeping quarters on some occasions. The Clowns had to deal with segregationist practices at hotels and restaurants, enforced through the Jim Crow laws of the era. On the field, the Clowns sometimes played tripleheaders, something unheard of in Organized Ball. During one tripleheader, Canova collected five hits in five official at-bats, with one of the hits coming against Satchel Paige. Casanova played so well for the Clowns that he drew interest from the Chicago Cubs. In late September, the Cubs signed him, with a promise of a minor league assignment in 1962. That spring, the Cubs assigned Casanova to their Double-A affiliate in the Texas League. The situation seemed promising, but once again ended in disappointment. Casanova appeared in a grand total of two games, came to bat one time and was then informed of his latest release. In three different minor league stints, Casanova had come to bat seven times, while drawing his release on three occasions. Barely 20 years of age, Casanova faced the premature end of his career. He became so discouraged that he actually gave up the game and opted for a more stable line of work: Construction. Thankfully, one team showed interest in bringing Casanova back to baseball. The Washington Senators, through a scout named John Caruso, contacted Casanova. For Caruso, this was his second go-round with Casanova. Caruso had tried to sign Casanova earlier, only to come down with an illness. “Caruso became ill and required an operation,” Casanova told Bob Addie of the Sporting News. “He was out of action six months and in that time he lost track of me.” This time, Caruso did not lose track of Casanova. Caruso told Casanova to give up the construction gig, return to baseball and stick with the sport. In October of ’62, Caruso and the Senators offered him a minor league contract. The following February, Casanova reported to Spring Training before being assigned to Geneva of the NY-Penn League.

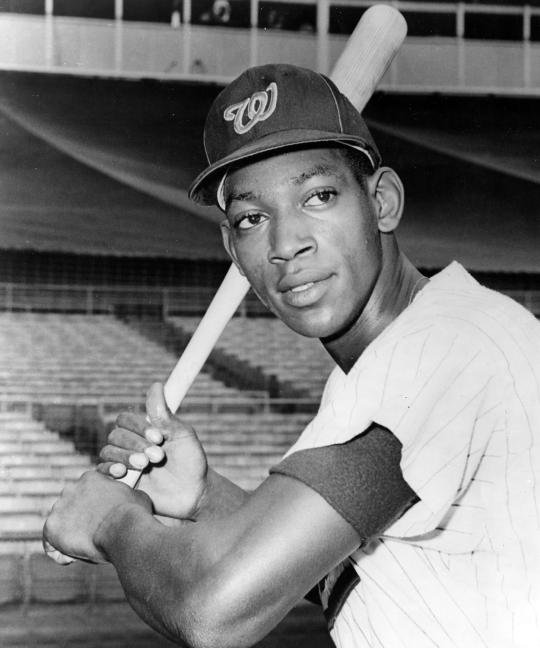

In contrast to the other organizations, the Senators gave Casanova a chance to play in the minor leagues. Playing a full season for Geneva, Casanova hit .261 with seven home runs, respectable numbers in a league known for pitching. Casanova returned to Geneva in 1964 and dominated the league. He hit .325, belted 19 home runs, and slugged .508. For the first time in his career, Casanova took on the tenor of a real prospect. Casanova’s excellent season at Geneva earned him a promotion to Burlington, a full season Single-A team in 1965. Casanova emerged as a workhorse behind the plate, appearing in 142 games. He continued to hit well, putting up a .287 batting average with eight home runs. By the summer of ’65 the Senators needed a boost at the catching position. Mike Brumley, the incumbent, struggled to keep his average above .200. When Casanova’s season ended, the Senators called him up for a late-season audition. Over a five-game stint with the Senators, Casanova batted .305. While it was a small sample size, it made a good first impression. Rather than keep him with the big club in 1966, the Senators decided to take a more conservative approach with Casanova and assign him to their Double-A affiliate at York in the Eastern League. Casanova hit only .211 over a handful of bats, but a wave of injuries to the Senators’ catching position put the team in a desperate situation. The Senators promoted Casanova from Double-A, making him their starting catcher. In his first game, Casanova clubbed a home run against Fred Talbot, breaking up the right-hander’s bid at a no-hitter. By the end of his rookie season, Casanova had hit 13 home runs and shown himself to be a first-rate defensive catcher with his catlike quickness and cannonlike throwing arm. He struggled at times in calling games, but he had no trouble controlling the running game. He threw out 46 percent of opposing basestealers, making life easier for the Senators’ pitching staff. American League beat writers took note, giving Casanova enough support in the Rookie of the Year balloting to place him third behind George Scott and Joe Foy of the Boston Red Sox. In 1967, Casanova enjoyed a hot start to the season, but it was not until June 12 that he truly started to receive national attention. In a marathon game against the Chicago White Sox, Casanova played all 22 innings behind the plate, threw out a trio of potential basestealers, and delivered the game-winning hit. After the game, reporters and writers gathered around Casanova’s locker. A reporter from United Press International asked Casanova if the lengthy game had tired him out. “I’m not tired,” Casanova told UPI. “I could have gone another 10 innings,” Casanova said matter of factly. Casanova’s comments typified his love of playing the game. In turn, the Senators loved Casanova’s on-field enthusiasm, which made him a fun player during a conservative era. They appreciated his hustle and exuberance, the way that he ran out to his position at the start of each inning. Washington fans also enjoyed the ritual of each at-bat. Instead of walking up to the plate, he practically ran toward the batter’s box. “Cazzie,” as he became known to his teammates, then took two all-out practice swings and settled into a deep crouch. Casanova’s fine play continued for much of the summer. First, he earned a place as a backup on the American League All-Star team. By the end of the season, Casanova had thrown out 49 percent of baserunners, a remarkable figure.

Casanova’s throwing arm made opponents and the media take notice. Prior to one game against the New York Yankees, Casanova took part in a pregame drill. As he made one pulsating throw after another to second base, Yankees broadcaster and former big league catcher Joe Garagiola approached Casanova. “Don’t you ever get a sore arm?” asked Garagiola, as quoted by the Sporting News. “The Army could use you as a secret weapon. I never saw a gun like that.”

Casanova also showed power with his bat, hitting nine home runs. Casanova contributed so much with his catching and hitting that he received some support for league MVP Award in October, finishing 21st in the balloting. If not for a late-season slump in August and September, Casanova might have finished even higher.

If there was a weakness to Casanova’s game, it was a lack of patience at the plate. He drew only 17 walks in 141 games. His on-base percentage fell below .280. If anything, he swung more aggressively in 1967 than he had as a rookie.

Casanova’s free-swinging approach caught up to him in 1968. It was already a difficult environment for hitters, being the Year of the Pitcher, but Casanova’s overaggressive style exacerbated the problem. He started the season so badly that his batting averaged settled in at .181 by the end of June. The Senators decided that Cazzie’s exceptional defense could not make up for a complete lack of hitting. They sent Casanova to Triple-A Buffalo, where they hoped he could regain better offensive form.

Over the next month, Casanova batted .272 with two home runs, numbers that were deemed good enough to bring him back to Washington. Over the balance of the season, Casanova hit a bit better, raising his final average to .196. With an on-base percentage of .210 and a slugging percentage of .252, Casanova’s lack of production simply could not be carried. His hitting also seemed to affect his defensive play. He threw out 38 percent of basestealers, a decent number, but one that was off the pace of his first two seasons.

The Senators also wondered about Casanova’s lifestyle. He had developed a reputation for living in the fast lane. Drinking and dancing until the late hours, he sometimes missed the curfew established by manager Jim Lemon. On more than one occasion, Lemon fined Casanova.

In spite of all of the problems of 1968, the Senators stuck with Casanova as their starting catcher. They hope that he would benefit from the presence of a new manager in Ted Williams, who urged his hitters to be more patient and selective during their at-bats. Casanova drew a few more walks, a career high of 18, but didn’t improve as much as Williams would have liked.

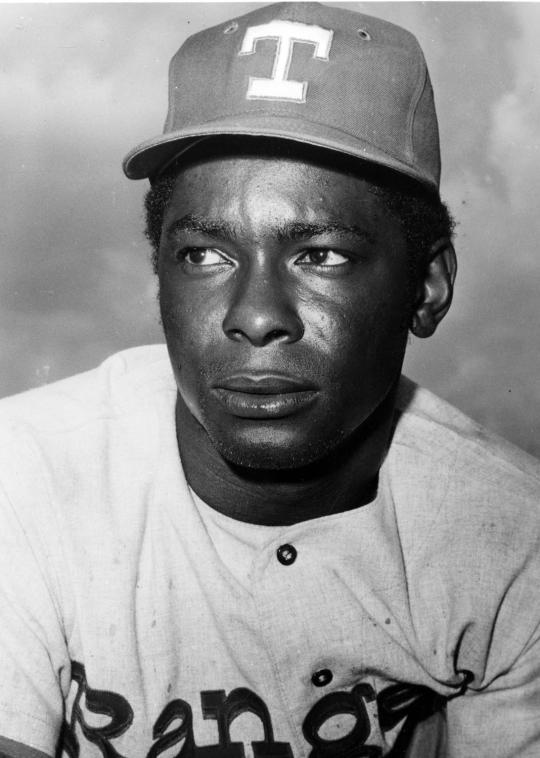

By 1970, Casanova began to lose playing time. Fast approaching his 30th birthday, Casanova was headed out of town, as the Senators prepared for life as the Texas Rangers. At the famed 1971 winter meetings, where numerous future Hall of Famers changed uniforms, the newly named Rangers traded Casanova to the Atlanta Braves for another catcher, Hal King.

The Braves already had a strong hitting catcher in Earl Williams, the winner of the Rookie of the Year Award in 1971. But the Braves wanted a strong backup, a more defensive-minded catcher who could serve as a mentor to Williams. Casanova filled the role capably. While he hit only .209 in 49 games, he excelled behind the plate. He threw out eight of 18 baserunners, achieving a success rate of 44 percent.

After the 1972 season, the Braves decided to trade Williams, sending him to Baltimore. That decision created more playing time for Casanova, who would platoon with the left-handed hitting Johnny Oates. On Aug. 5 of that season, Casanova became a part of history. He caught a no-hit game pitched by Phil Niekro. Niekro threw knuckleballs almost exclusively that day, but the surehanded Casanova handled every pitch without incident.

After the season, Casanova started up a business venture in Venezuela, where he usually spent his winters. He opened up a night club, which he co-owned with Chicago White Sox outfielder Pat Kelly and his brother Leroy, a running back in the National Football League. It was the perfect business venture for the man who enjoyed the night life.

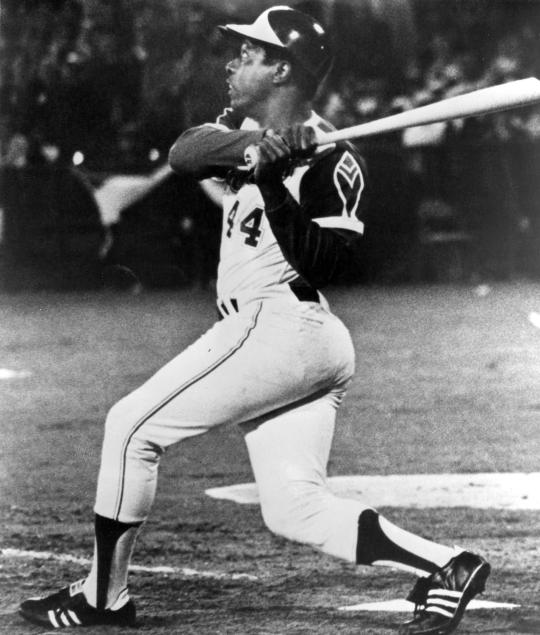

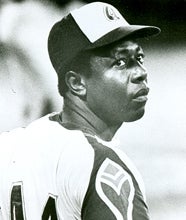

With his outgoing personality, Casanova made plenty of friends with the Braves. One of them was Hank Aaron, who had also played in the Negro Leagues with the Clowns, albeit at a much earlier time. Sharing stories of their tenures with the Clowns, the two men became close friends.

The 1974 season placed Aaron in the spotlight. On Opening Day, Aaron hit his 714th home run, tying him with Babe Ruth. Less than a week later, he hit No. 715. As Aaron tied and then broke Ruth’s home run record, Casanova watched with special interest. Shortly thereafter, Aaron came to the plate and hit No. 716. Casanova, who happened to be in the Braves’ bullpen at the time, caught the ball and gave it to Aaron.

Casanova spent much of his time in the bullpen that summer, as the Braves reduced him to the role of third-string catcher. Limited to 104 at-bats in 42 games, Casanova batted .202. He did play well defensively while tutoring the young tandem of Oates and Vic Correll.

The Braves brought Casanova to Spring Training in 1975, but the atmosphere around the team felt different, with Aaron having been traded to Milwaukee. The Braves gave Casanova a chance to make the team as a backup to a young catcher they liked, the wonderfully named Biff Pocoroba. Injury determined Casanova’s fate; he suffered a bad elbow late in the spring. During the final days of the spring, the Braves released the 32-year-old Casanova.

No one showed interest in signing Casanova, who opted for retirement after 10 seasons in the big leagues. With his release, only one Negro Leagues alumnus remained in the major leagues: His friend, Hank Aaron. (Two other ex-Negro Leaguers, Harry Chappas and Minnie Minoso, would appear in games in later years, but they were not active in 1975.)

After his playing days, Casanova and two other alumni of the Negro Leagues created their own baseball academy. Affectionately known as “Paul’s Backyard,” the academy became a safe haven for low-income youngsters to play the game and learn how to play it the right way.

Casanova continued to run the academy into his 70s. Back problems, along with respiratory difficulties, forced him into a wheelchair. In 2017, he made his final public appearance at the Miami All-Star Game, taking part in the event known as Fan Fest. Despite being in considerable pain, Casanova answered questions from the media and talked to the fans. Less than a month after his appearance, Casanova died. He was 75.

His death hit the baseball communities in Cuba and Venezuela hard. He had become a legend in both countries, first as a player and second as a teacher of the game. Through his academy, he continued to teach, until his health no longer allowed him to do so. I guess that’s only fitting for Casanova, a good man whose 1973 Topps card did a little bit of teaching, too.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital & outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum