- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Gerry Moses

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Gerry Moses

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

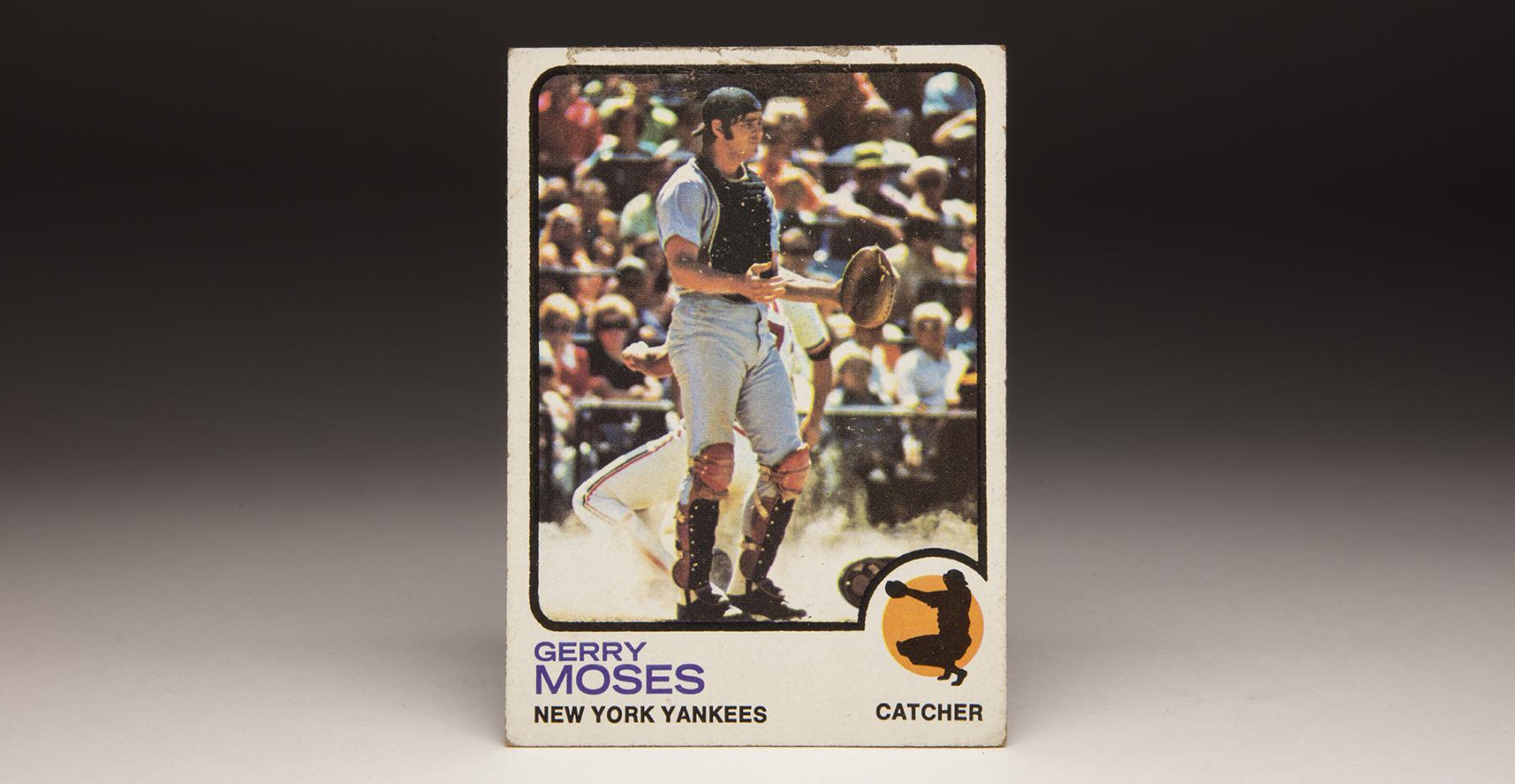

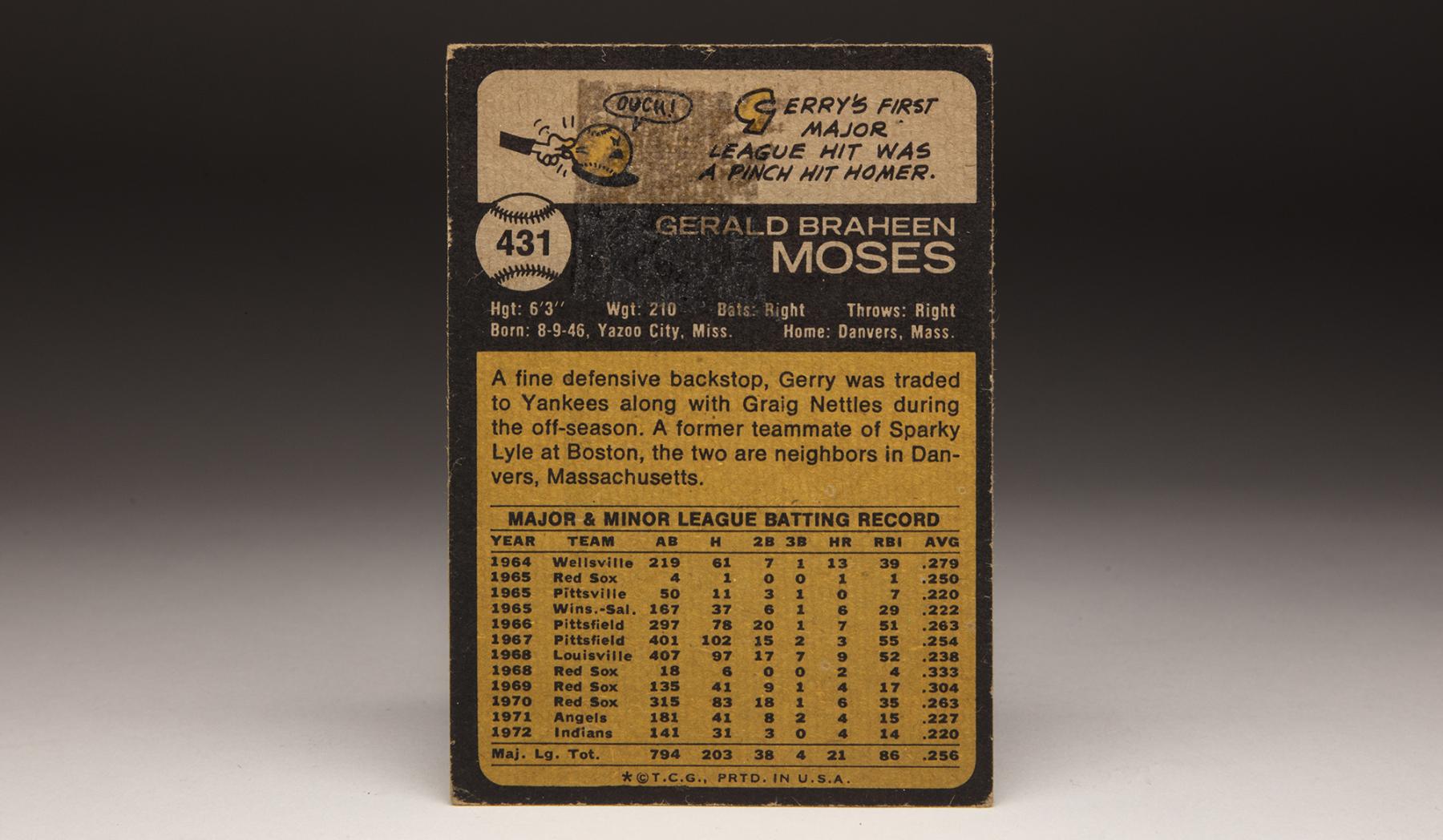

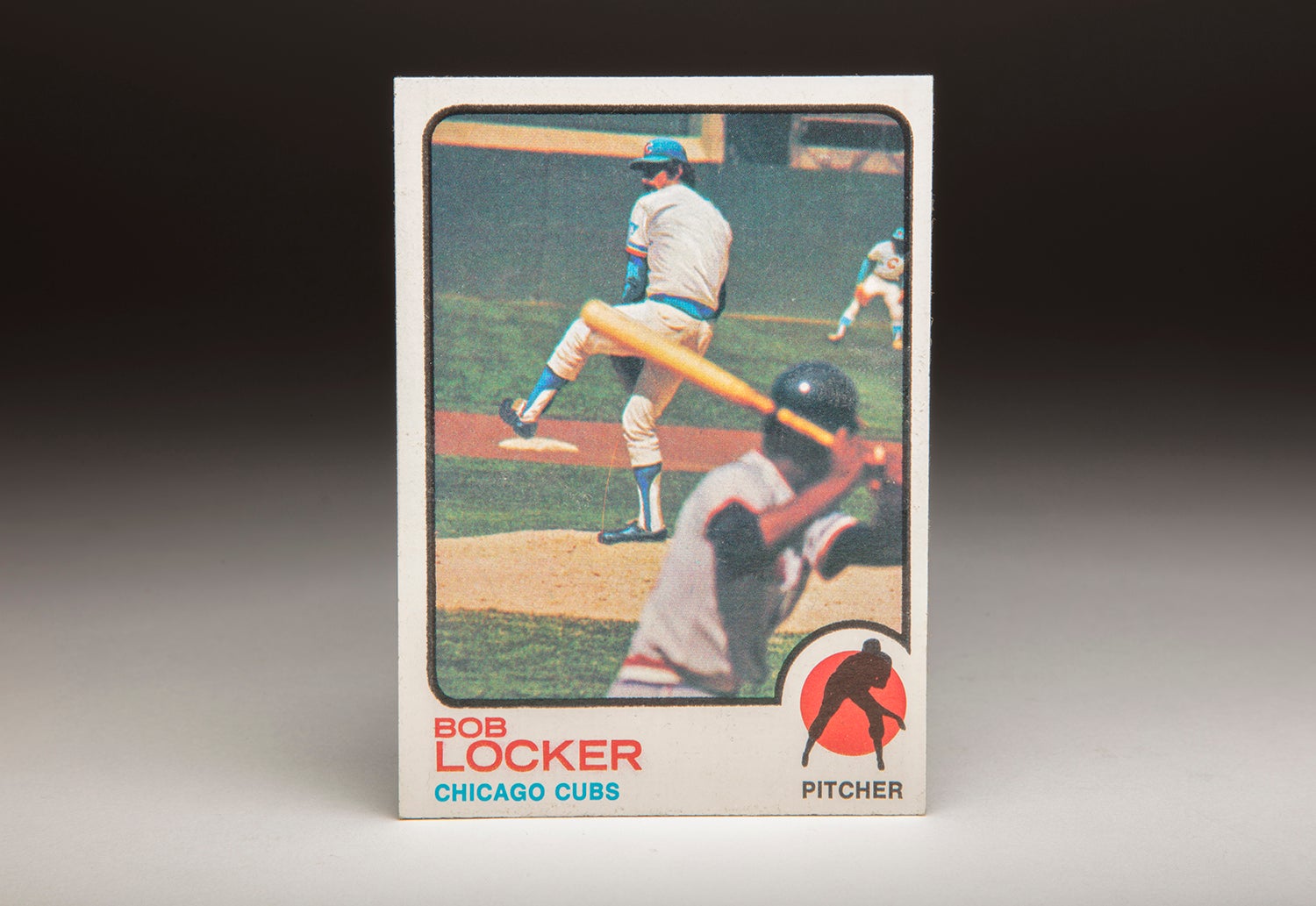

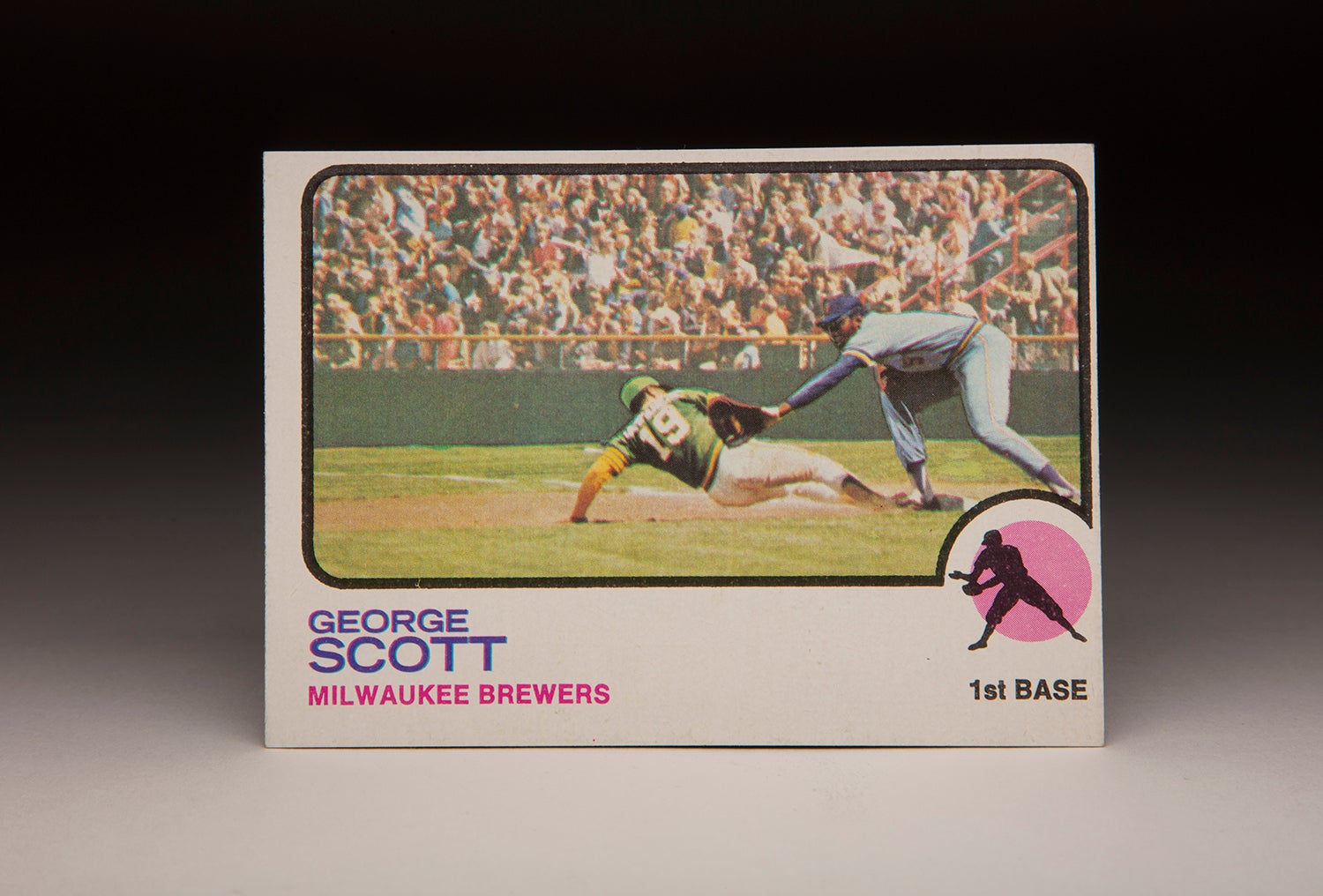

I have lots of questions when it comes to the 1973 Topps card of the late Gerry Moses. First off, why is he labeled as “Gerry” on this card, when his first name was spelled as “Jerry” for most of his career? Second, who is the Baltimore Orioles baserunner sliding into home plate while being partially obscured by Moses’ upright body? And finally, what uniform is Moses, who was traded from Cleveland to New York during the winter that preceded the 1973 season, actually wearing on this card? Let’s do our best to come up with some relevant answers.

During Moses’ career, many print references in daily newspapers listed him as Jerry, as does his current entry at the excellent Baseball-Reference.com. Yet, most of Moses’ Topps cards listed him as “Gerry.” In addition to the 1973 card, we can find “Gerry” on his 1969, 1970, ’71, ’72, and ’74 cards. But then, rather mysteriously and without explanation, Topps switched to “Jerry” on his 1975 card, the final one that the company issued for him.

Perhaps Topps made the switch to match Moses’ facsimile autograph on his 1975 card. On that card, Moses signs as “Jerry.” In contrast, Moses’ 1971 card features a facsimile autograph signed as “Gerald,” which was his real first name. (Topps did not have faux autographs on their 1972, ’73, or 74 issues, so they’re of no help here.)

I’m guessing that this is how Topps came up with Gerry: When they saw that his real name was spelled “Gerald,” they probably assumed that his nickname, “Gerry,” also featured a “G.” Not seeing how he actually spelled “Jerry” until he submitted his signature for the 1975 set, Topps realized its mistake and made the change. And just to confirm, it’s not only facsimile autographs of Moses that show his preference for “Jerry.” In all of the actual Moses autographs I’ve spotted on the Internet, Moses always signed as “Jerry” Moses.

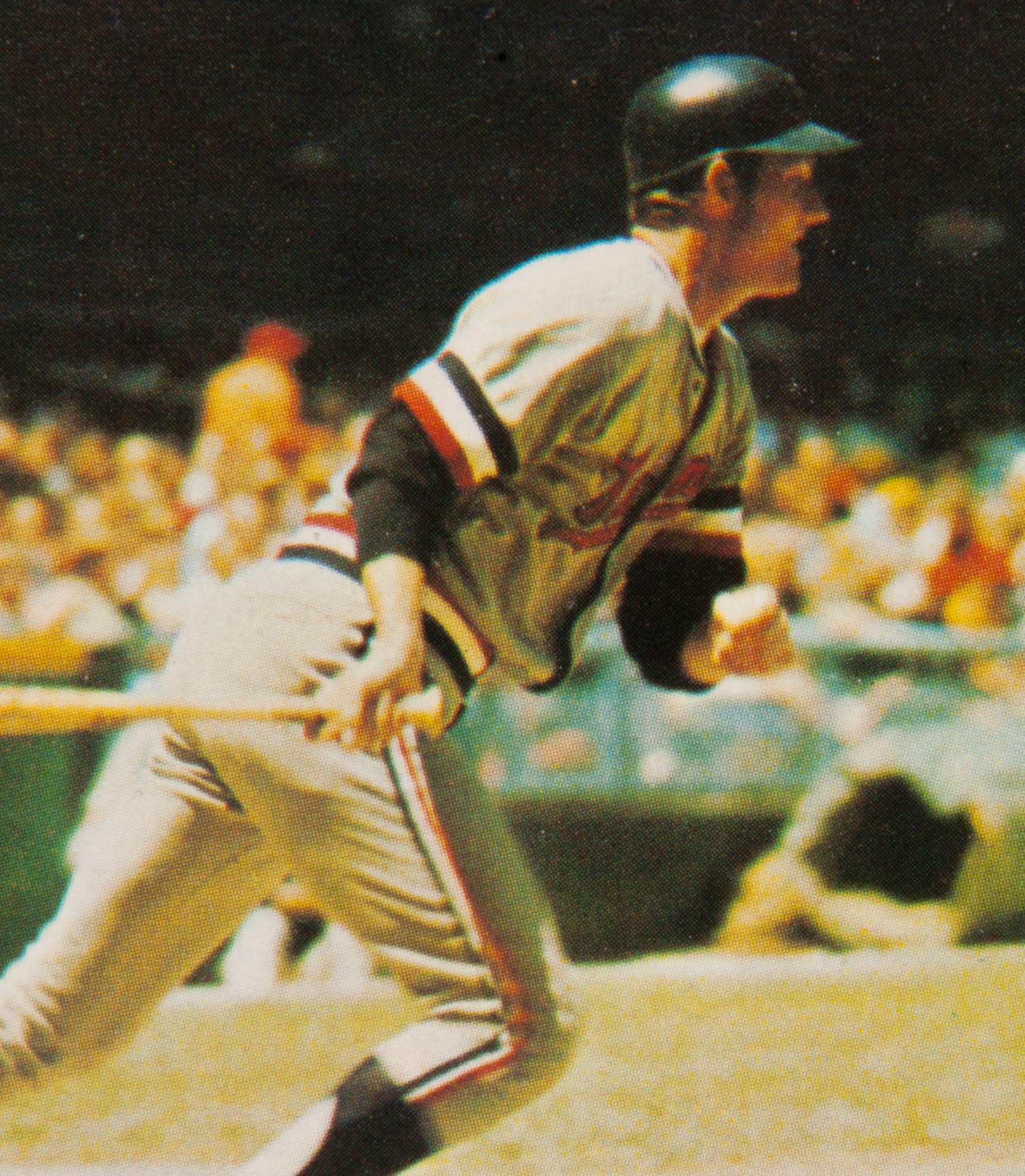

As for the Orioles’ baserunner on the card, we really have only two clues on which to rely. The runner appears to be white, and it looks like he has a “7” on the back of his jersey. Assuming that this photograph was taken at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium during the 1972 or 1971 seasons, we can narrow the choices down to a couple of possibilities. If the No. 7 is a standalone number, then it is Orioles shortstop Mark Belanger, who wore that number both seasons. If the 7 is the second number, then it could be pitcher Pat Dobson (No. 37), the only other Oriole to have a 7 in his number in 1972. The other possibility is pitcher Orlando Pena (No. 27), who had a 7 in his number in 1971, but also happened to be black. Given that Dobson was a pitcher and probably didn’t run the bases all that frequently, my guess is that it’s Belanger. Let’s also remember that most pitchers of that era wore windbreakers on the bases. There is no windbreaker evident here, so that lends even more credence to the Belanger theory.

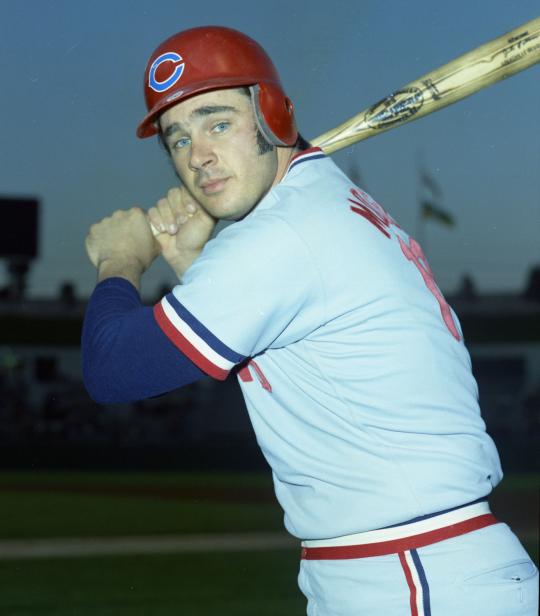

With those two matters resolved, that leaves the question regarding the uniform that Moses is wearing. At first glance, it looks like the Yankees’ road uniform of that era, making it a match for the team designation on the card. But Moses did not play for the Yankees in 1972, the likely time frame for when the photograph was taken; he was still a member of the Cleveland Indians. Upon initial review, this doesn’t look like the Indians’ road uniform, which featured red caps and red trim on the sleeves.

So maybe it’s actually a photograph from the 1971 season, when Moses was still with the California Angels. But it doesn’t look like the Angels’ road uniform of that season, either. Those uniforms also had red trim. A closer look, however, might offer a clue.

It’s hard to tell, but the bill of Moses’ cap appears to be a color other than the dark blue of the cap crown. Could it be that the bill of the cap is red? If it is, that would make it a match for the Angels’ cap of 1971.

My guess is that this is a photograph from the 1971 season and that Topps airbrushed the red stripes out of the jersey to make it resemble the Yankees road uniform. Topps also received an assist from Moses’ catcher’s gear. The chest protector naturally blocks out the Angels’ name on the front of the jersey, while the backward cap also prevents us from seeing the Angels’ Halo logo.

The end result is a subtly airbrushed card that has Moses wearing a very believable-looking uniform. Standing upright, Moses looks exactly like a big league catcher should look. I also like the way that Moses is holding his mitt hand and his bare hand apart, in a bit of a frustrated manner, as the runner safely crosses the plate. It’s as if Moses is saying to the infielders, “Hey, where’s the ball?”

Another question that would have been appropriate for Moses to ask was this: “Where am I playing?” Like many backup players, he was a journeyman who bounced from team to team, starting with his minor league days in the mid-1960s.

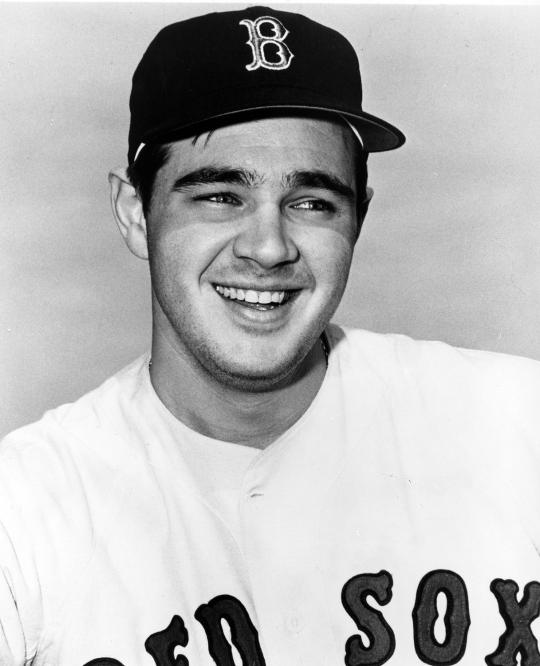

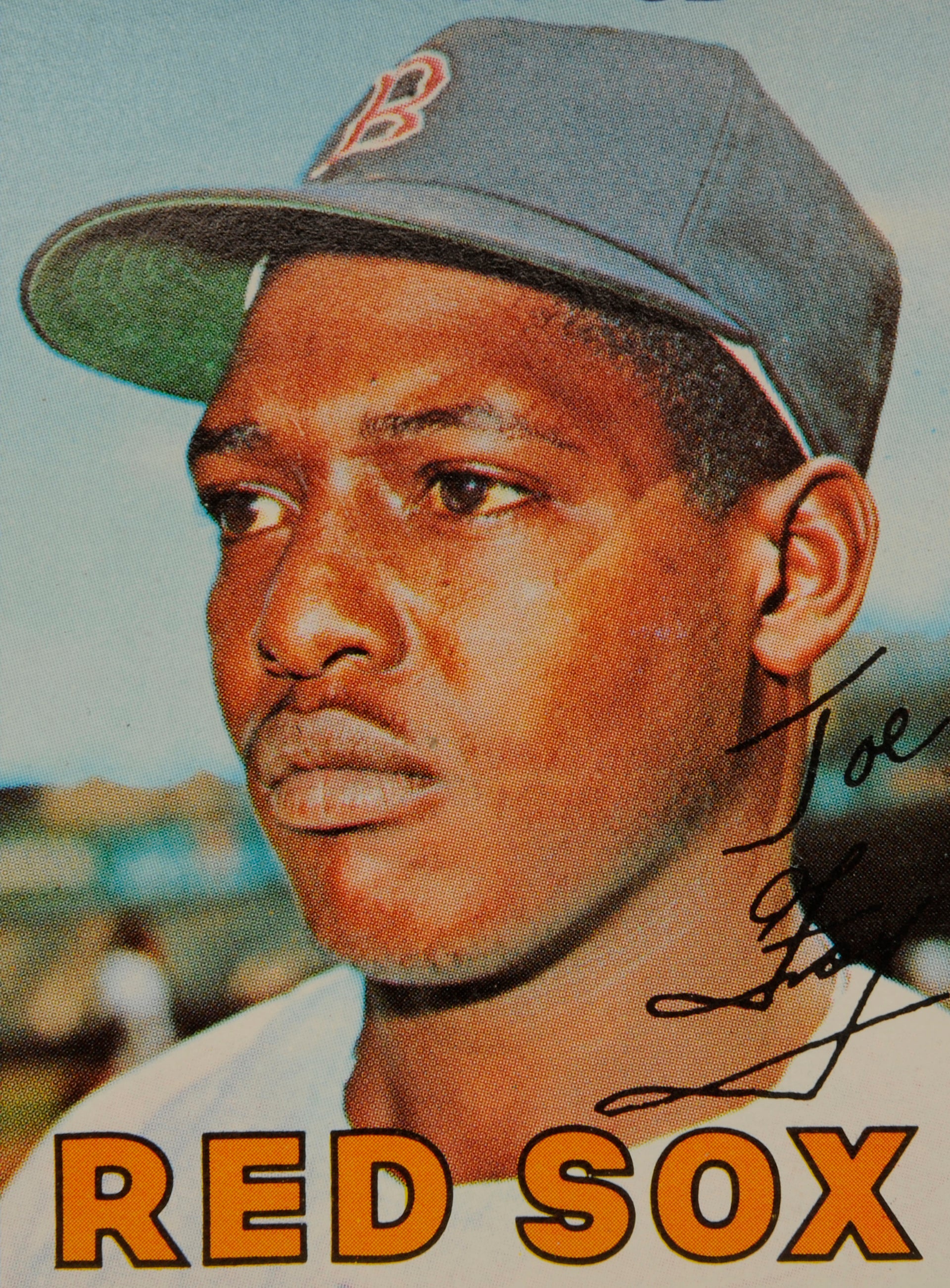

Moses turned pro in 1964, when he decided to forego several college football scholarship offers from the Southeastern Conference. Instead of pursuing a career as a college quarterback, Moses opted for a professional contract as a highly touted catcher with the Boston Red Sox, who outbid five other major league teams. The Sox assigned him to Wellsville of the NY-Penn League. Although Moses was just 17 years old, he did very well in his debut, hitting .279 with 13 home runs in only 67 games.

Based upon the bonus rules of the time, the Red Sox had to put Moses on their roster for part of the 1965 season or else risk losing him to another team in a wintertime minor league draft. Moses made his major league debut in May, belting a home run for his first major league hit, but soon found himself back in the minor leagues. He split the season between Double-A Pittsfield and Class A Winston-Salem, hitting in the .220s at both stops. But the Red Sox felt that he would develop power as he progressed through their system.

In 1966, Moses reported to the Sox’ Spring Training camp in Winter Haven, Fla. He struggled with his throwing, even with the routine process of tossing the ball back to the pitcher. So the Red Sox sent him back to Pittsfield, allowing him to overcome his throwing mental block and remain in one place for the entire summer. Moses played well enough to earn a spot on the Eastern League All-Star team.

The trade devastated Moses, who had known no other organization besides the Red Sox. Although Moses was not a star, his engaging manner and strong work ethic had made him extremely popular with fans and teammates in Boston.

At the time, the Angels needed catching help, but Moses had to settle for a time-sharing arrangement with two other catchers, John Stephenson and Jeff Torborg. Moses struggled at the plate, putting up an OPS of .625, the worst mark of his career to date. And like many of the Angels players, Moses became critical of manager Lefty Phillips and the general atmosphere of dissension in the California clubhouse.

Within the days of the 1971 season ending, the Angels sent Moses on his way, trading him and Alex Johnson to the Cleveland Indians as part of a deal for veteran outfielder Vada Pinson. Now a backup to Ray Fosse, Moses played sparingly. He excelled behind the plate, but put up even poorer offensive numbers for the Indians than he had in California.

Rather than rush Moses up the minor league ladder, the Red Sox gave him another season at Pittsfield in 1967. His offensive numbers remained middling to fair, but he still earned selection to another All-Star team. When Pittsfield’s season came to an end, the Red Sox brought him up to Boston to help the team during its wild American League pennant race. Moses never did appear in a game during the stretch run in 1967, but did serve as a bullpen catcher for manager Dick Williams. When the Red Sox clinched the pennant on the final day of the regular season, Moses celebrated the event with his more established teammates.

After the euphoria of the “Impossible Dream” in 1967, Moses had to deal with the letdown of returning to the minor leagues in 1968. This time, the Red Sox assigned him to Triple-A Louisville, giving him the chance to play for manager Eddie Kasko. Moses came to regard Kasko as his mentor, the man who taught him more about the game than any other manager.

After a good season at Louisville, the Red Sox rewarded Moses with another late-season call-up. This time, Moses received his chance to play. In 18 at-bats, he collected six hits, including two home runs.

By 1969, Moses was ready to move into a three-headed catching rotation with two older players, Russ Gibson and Tom Satriano. Although Moses played sporadically as part of an unusual time-sharing set-up, he did well. Not only did he excel behind the plate, but also batted a career best .304.

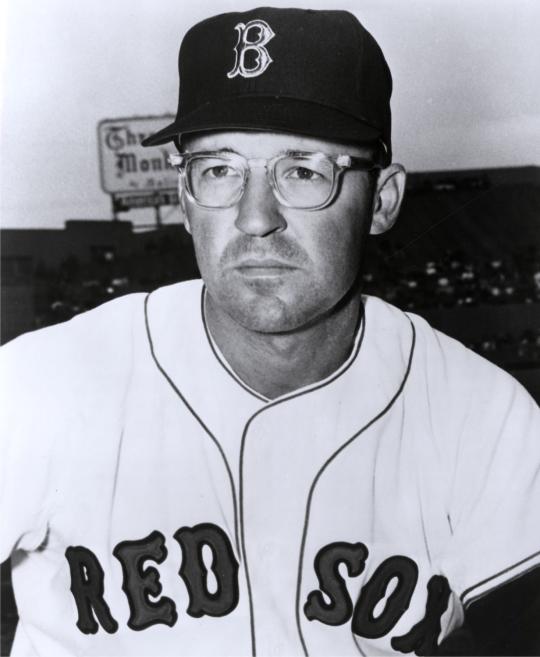

In 1970, the Red Sox made Kasko their manager. Kasko liked Moses, making him the Red Sox No. 1 catcher. Moses played so well – both as a hitter and as a receiver – over the first half of the season that Baltimore manager Earl Weaver selected him as a reserve to the American League All-Star team.

As well as Moses playing through mid-July, he could not sustain his All-Star level in the second half. Injuries took their toll, especially a painful split and torn fingernail to one of the fingers on his right hand. With the injury making it harder to grip the bat, Moses’ hitting tailed off in August and September, his batting average falling to .262.

As the season came to an end, Moses had no idea that he would never again suit up for the Red Sox. Less than two weeks after the season finale, Moses received a phone call telling him that he had been traded to the Angels. The trade sent Moses and Tony Conigliaro, among others, to the Angels for promising infielder Doug Griffin, outfielder Jarvis Tatum and right-handed pitcher Ken Tatum. The Red Sox believed that Moses was expendable because of the pending arrival of a promising young catcher named Carlton Fisk, who would make his major league debut the following season.

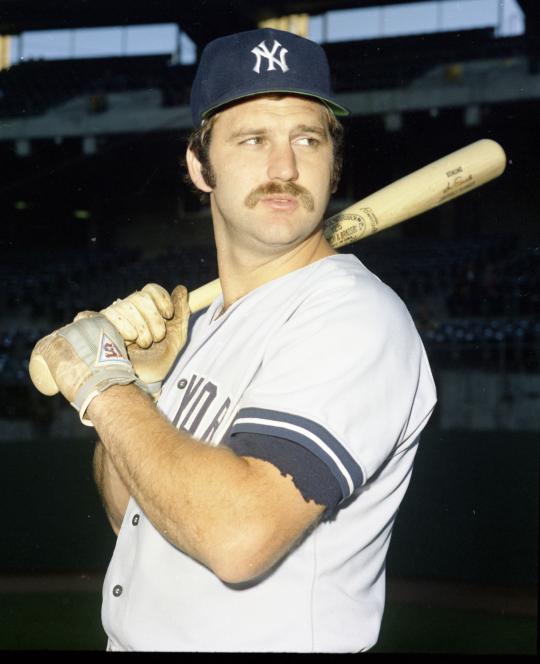

The carousel of changing teams continued for Moses that winter. The Indians sent him and Graig Nettles to the Yankees for a package headed up by catcher/first baseman Johnny Ellis.

Moses faced an even more daunting challenge when it came to playing time. He would now have to back up Thurman Munson, one of the American League’s top catchers. Munson rarely took days off, resulting in Moses appearing in only 21 games.

With the Yankees, Moses became close friends with veteran pitcher Sam McDowell, who praised him for his work with the team’s pitchers. Although Moses fit in well in the Yankees clubhouse, he was part of an overload of catching, which the Yankees decided to alleviate through a trade in Spring Training of 1974. As part of a complicated three-way trade that also involved the Indians, the Yankees sent him to the Detroit Tigers.

Upon hearing the news, Moses expressed his pleasure. “I’m the happiest person in the world. You knew the same guy was going to catch 140 games every year,” Moses told the Sporting News, in referring to Munson. “He’s unbelievably good.”

The trade also provided a quick reunion with Ralph Houk, who had been his manager in New York. At first, Houk planned to use Moses as a backup to veteran Bill Freehan, before eventually moving the incumbent to first base and clearing the way for Moses to receive more playing time. Moses appeared in 74 games, the most of any Tigers catcher, while hitting .237 with four home runs.

The 1975 season would turn out to be the most tumultuous – and the last – of his career. In January, the Tigers sold Moses on a conditional basis to the New York Mets. Moses would never appear in a game for the Mets; at the end of April, the Mets offered him back to the Tigers before selling his contract to the San Diego Padres, where he backed up Fred Kendall. Appearing in only 16 games with San Diego, Moses found himself moving on again in July, when the Padres sold him to the Chicago White Sox. Moses appeared in only two games for the Sox before drawing his release in September.

Moses was still only 28 and in good shape physically, but the constant shuttling from team to team, coupled with his relatively low salary, convinced him to give up the game. Wanting to better support his family, he opted for a more stable job in the travel industry. After that, he went to work in the food industry, where he enjoyed considerable success.

Settling in eastern Massachusetts, Moses remained a popular figure in retirement. He became active in charities, particularly the Red Sox’ celebrated cause known as the Jimmy Fund. Another former Red Sox player, Mike Andrews, headed up the Jimmy Fund for years, and often relied on Moses for help in fundraising. Moses made frequent public appearances on behalf of the charity, especially at golf outings, where he reunited with former teammates and made new friends among fans. He and Andrews also collaborated on a long-running youth baseball camp.

In the 1980s, Moses added the newly formed Major League Baseball Alumni Association to his list of efforts. With his friendly, outgoing personality, Moses helped the association gain a foothold in its early years. Moses continued to make public appearances for the alumni and the Red Sox even after falling into ill health.

In March of 2018, Moses succumbed to a combination of dementia and aphasia, the latter a disease that affects speech and the ability to process language. He was 71. Throughout New England, Moses’ passing became a major story, owing largely to his common man touch and charismatic personality. Many of his former teammates offered their praise, including Mike Andrews. “I don’t think I ever met a better man in my life,” Andrews told Oliver Macklin of MLB.com. “Everyone loved Jerry. He’s just a lovable guy, and he loved everybody back… When I look at people that made the most of their life after baseball, Jerry is at the top. He took care of his family. Very family-oriented.”

The news of Moses’ death also brought back some fond memories of one of the more intriguing cards from 1973 Topps. It’s a card that Moses often received in the mail, his many fans requesting him to sign it. Knowing Moses, it’s a good bet that he signed every one.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame