- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps George Scott

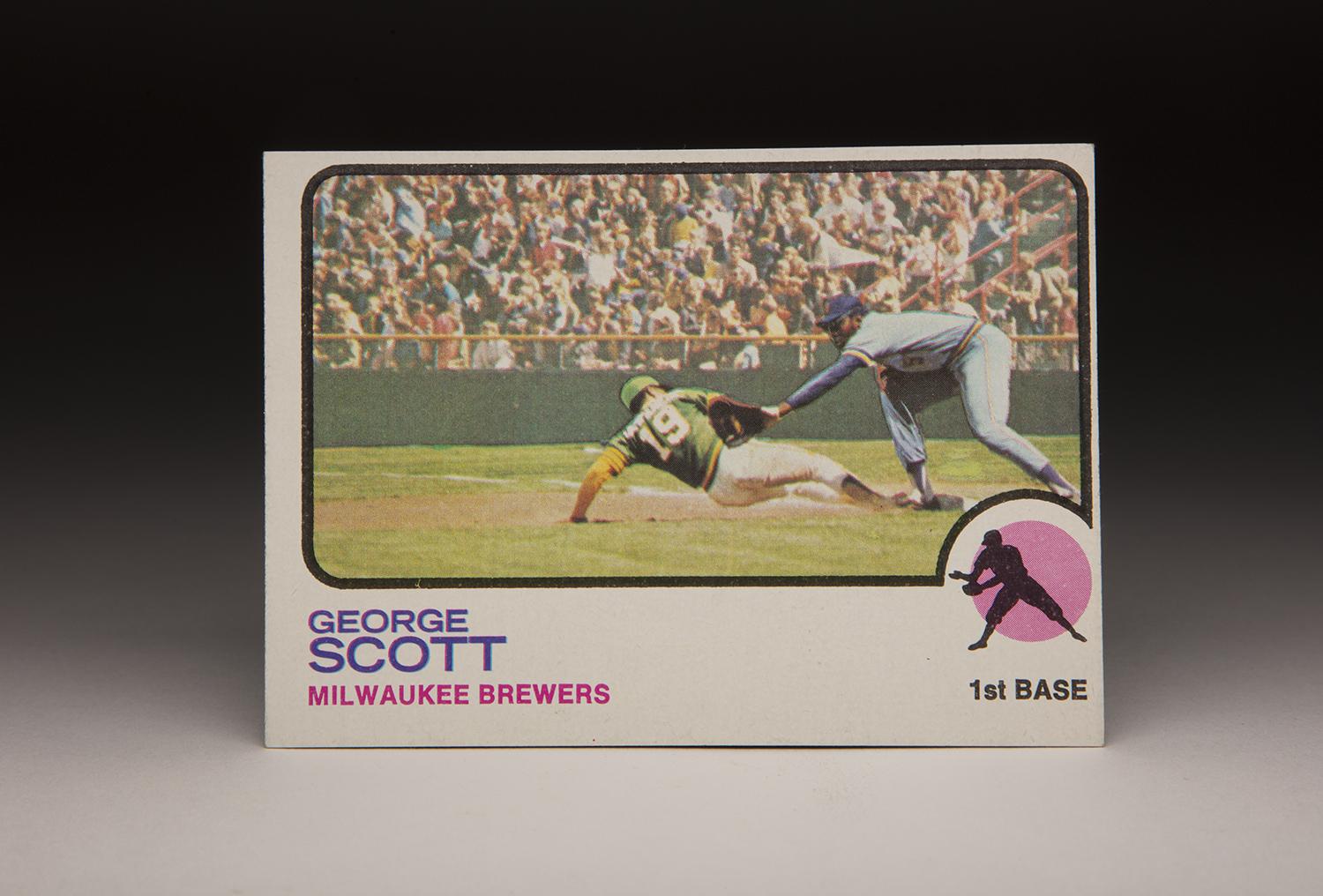

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps George Scott

Some of the choices that were made in putting out the wonderful 1973 Topps set remain a puzzlement to this day.

Why were so many action shots taken from so far away? Why did Topps crop Terry Crowley’s photograph in such a way so as to give equal billing to Thurman Munson, making it seem like Munson’s card? Why does Luis Alvarado’s card show us the parking lot (including a 1972 Chevy) at the White Sox’s Spring Training ballpark? Why does Steve Garvey’s card show us more of Wes Parker, who is blocking Garvey’s face from our view?

Of all these delightful mysteries, this is the 1973 Topps card that puzzles me the most. We know that George Scott, who is stretching to receive a throw, is the featured player, and that Bert Campaneris is sliding feet-first into first base, trying to beat the tag from “The Boomer.” There is no mistaking the identity of those players, though it does seem like a strange coincidence that Campaneris is featured on so many cards of other players in the 1973 set.

No, the real mystery has to do with the background of this card. When you look at the outlines of Campaneris and Scott against the stands down the first base line at the Oakland Coliseum, something doesn’t look quite right. The photo doesn’t look natural. Instead, it appears that Scott and Campaneris have been superimposed onto the stands. Somewhat similarly to a blue screen technique used in a film, two different photos have essentially been pasted together to create a surreal look at the Coliseum.

If you’re still doubting that one photo has been superimposed over the other, then take a look at the fans in the stands. Ordinarily, the fans would be looking at first base, to see the result of the pickoff attempt. But they are not. They are looking in different directions, mostly toward the outfield, with little interest on what is transpiring at first base. These fans appear to be in attendance at a different game, based on the directions of their collective stares.

Why would Topps do this? Why take the foreground figures of Scott and Campaneris, along with the playing field, and overlay them onto a stadium background from a completely different game? What would be the point of making such a radical change to the card?

I’ve read one theory that says that the background stands in the photograph are actually from County Stadium in Milwaukee, and not from the Oakland Coliseum. That theory maintains that Topps did not want to use a photograph that showed many rows of empty seats in Oakland, so they took a shot from a busier County Stadium, or some other locale, to give the card a more appropriate background.

I don’t know if the theory holds true, but it’s as good as any explanation as I’ve heard. Whatever the reasoning, the card is unusual and offbeat, which is most fitting for a player like George Scott.

Scott’s professional baseball story began more than a decade earlier; in 1962, he signed his first pro contract with the Boston Red Sox’ organization. The scout who signed him, Ed Scott (no relation), believed that George was a better hitter in high school than Hank Aaron had been. Ed Scott had first-hand knowledge, having signed Aaron years earlier.

Scott played three full seasons in the minor leagues. It’s hard to believe in retrospect, but Scott actually played 24 games at shortstop in 1963 before finally being moved to the infield corners in ’64. In 1966, he reported to the Red Sox’s Spring Training camp, but was given only the slimmest chances of making the Opening Day roster. Not only did Scott make the team, but he beat out the favorite, Joe Foy, for the starting third base job. (It was Foy, by the way, who came up with Scott’s memorable nickname of “Boomer.”)

One week later, the Red Sox switched Scott to first base, where he would spend the majority of time that summer. Scott tormented American League pitching, raising his batting average to .330 at one point while also hitting with power. His first-half performance earned him a berth on the American League Al-Star team, where he started at first base. For the season, Scott would hit 27 home runs and place third in the Rookie of the Year voting.

After the season, the Red Sox hired Dick Williams as their manager, who surprisingly announced that Scott would have to beat out another promising young hitter, Tony Horton, for the starting first base job in 1967. Rather than complain, Scott became determined to improve as a hitter, and played so well in Spring Training that he won the first base job again. But as the season progressed, Scott irritated Williams with his growing waistline. On several occasions, Williams benched Scott for being above the mandatory weight limit.

When Scott did play, he hit well. The so-called “sophomore jinx” seemingly had little effect on the young slugger. In fact, despite a brief slump to start the season and the nagging questions about his weight, he played better in 1967 than he had in ’66. Reducing his strikeouts considerably, Scott put up an OPS of .839 and played a stellar first base, good enough to win his first Gold Glove Award. Scott’s fielding, in particular, made a believer out of Williams.

“Until I saw George Scott, I thought Gil Hodges was the greatest defensive first baseman I ever saw,” Williams told the Sporting News late in the 1967 season. “But Scott changed my mind.”

Playing the position with an agile grace that defied his size, Scott dazzled fans and observers with his flair at first base.

Scott’s summer of excellence in the field and at the plate coincided with a Cinderella season for the Red Sox, who shocked the baseball world by winning the AL pennant. In fulfilling their “Impossible Dream,” the Red Sox beat out three other rivals in a furious pennant race, and then came within a game of winning the World Series against a more experienced team from St. Louis.

Given his performance in ’66 and ’67, the Red Sox believed that Scott would remain a consistent run producer for years to come. But then came 1968, the dreaded “Year of the Pitcher,” which saw batting averages and home run totals plummet. The pitching-favorable conditions seemed to hurt Scott more than most. He started the season in a horrible slump, one from which he simply could not bounce back. At season’s end, his batting average sat at .171. He hit only three home runs in 124 games.

It was a lost season, but Scott found a remedy when he reported to the Winter League to play for Frank Robinson, the star for the Baltimore Orioles who worked as a manager during the offseason. Robinson worked with Scott on his mental approach to the game. Scott also sought out advice from one of his Winter League teammates, Roberto Clemente, who advised him to use a bigger bat. Clemente and Robinson got through to Scott, helping to turn his career around.

In 1969, Dick Williams moved Scott back to third base as a replacement for the departed Foy, who had been taken in the expansion draft. Scott played better, hitting 16 home runs and drawing 61 walks in 152 games. He put up similar numbers in 1970 before becoming a fulltime first baseman in 1971, when he hit 24 home runs, won the Gold Glove Award and earned some support for American League MVP.

The bounceback season had some thinking that Scott would remain in Boston for years, but the Red Sox surprised much of their fan base when they announced a blockbuster trade on Oct. 10. The massive deal sent Scott, 1967 hero Jim Lonborg, left-hander Ken Brett, outfielders Billy Conigliaro and Joe Lahoud, and catcher Don Pavletich to Milwaukee for 30/30 man Tommy Harper, right-handers Lew Krausse and Marty Pattin, and minor league outfielder Pat Skrable.

The massive 10-player deal took Scott away from friendly Fenway Park and placed him in the relatively unfamiliar location of Milwaukee’s County Stadium. The change in hitting environment had little effect on Scott, who hit 20 home runs and added the surprising dimension of speed to his game, stealing 16 bases for the season.

With the Brewers, Scott became a recognizable sight around the American League. With his massive body draped in Milwaukee’s form-fitting polyester uniform, Scott looked unusual to say the least. Furthermore, his ferocious, no-holds-barred swing intimidated pitchers on every team. And like Chicago’s Dick Allen, Scott wore a helmet, and not the standard cloth cap, when he played first base. Scott began to use the helmet in the field because of an incident that occurred during a road game. Some fans began throwing hard objects at Scott while he played first base. The incident convinced Scott that he should take a safer approach and wear a hard helmet at first base, something he continued to do for the rest of his career.

Over the next four seasons, Scott emerged as a star in Milwaukee, while also becoming extraordinarily popular with the fan base. In 1973, he batted a career-high .306 while actually increasing his power output. He was not quite as good in 1974, but still batted .281 with 17 home runs and took home another Gold Glove Award.

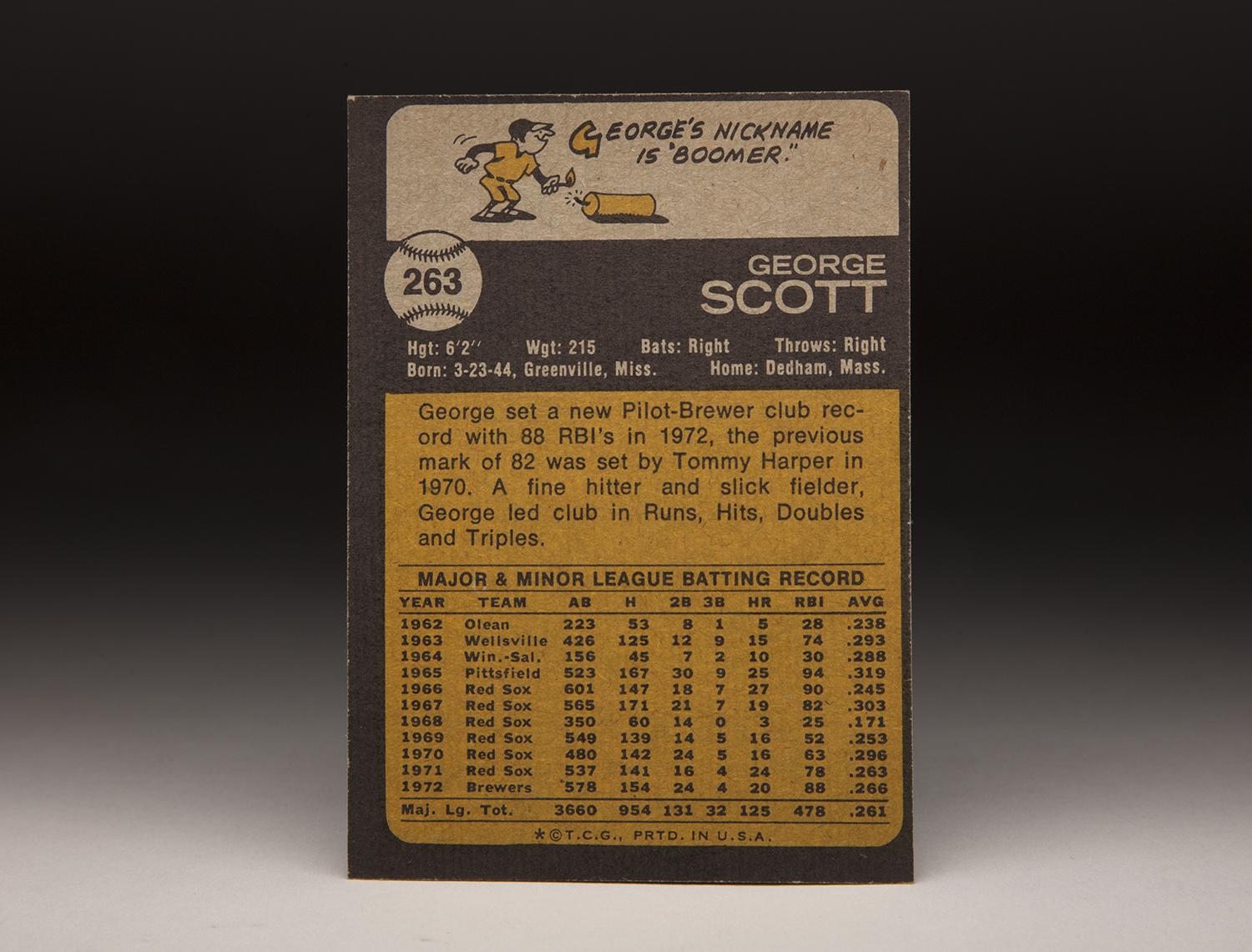

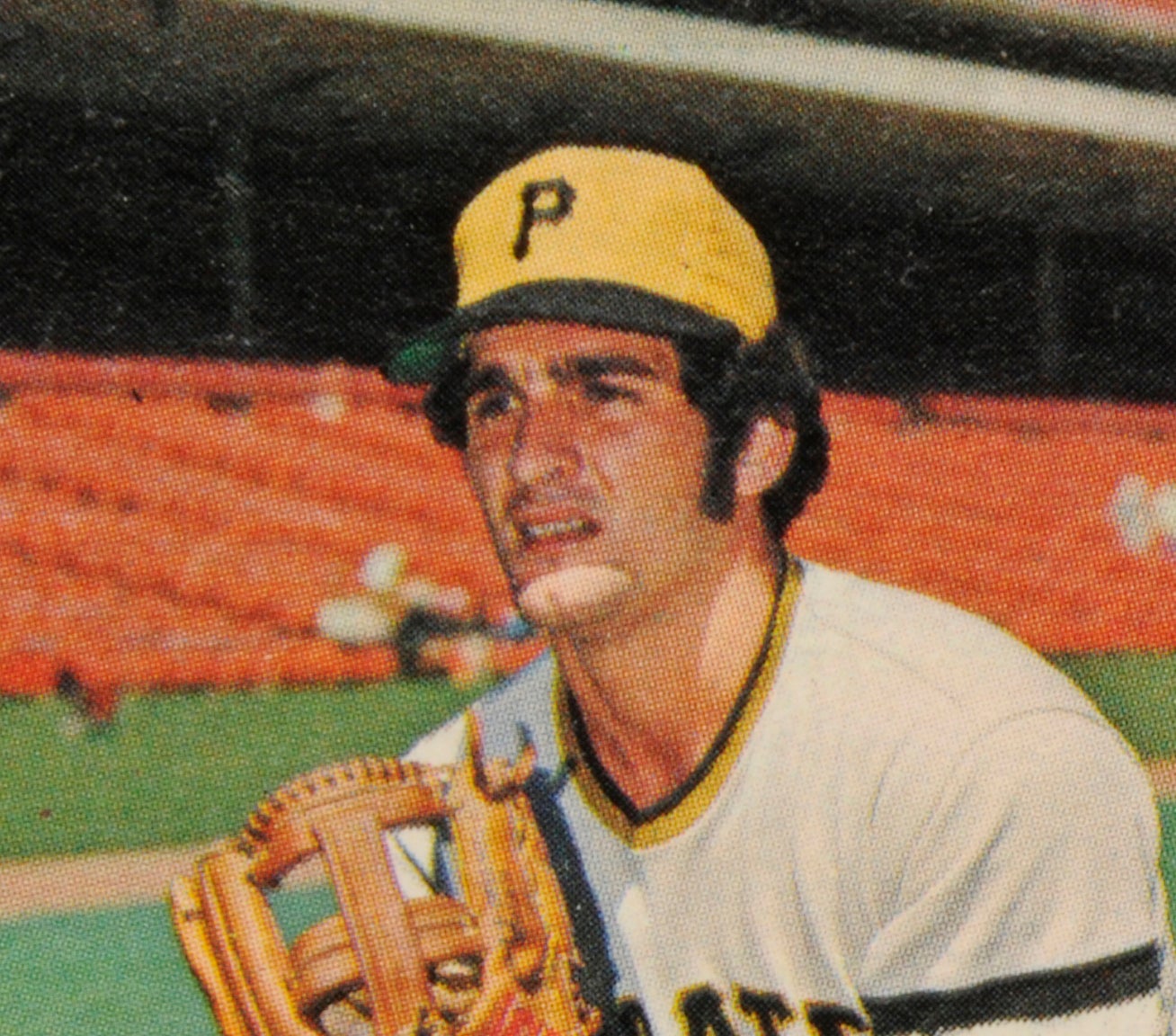

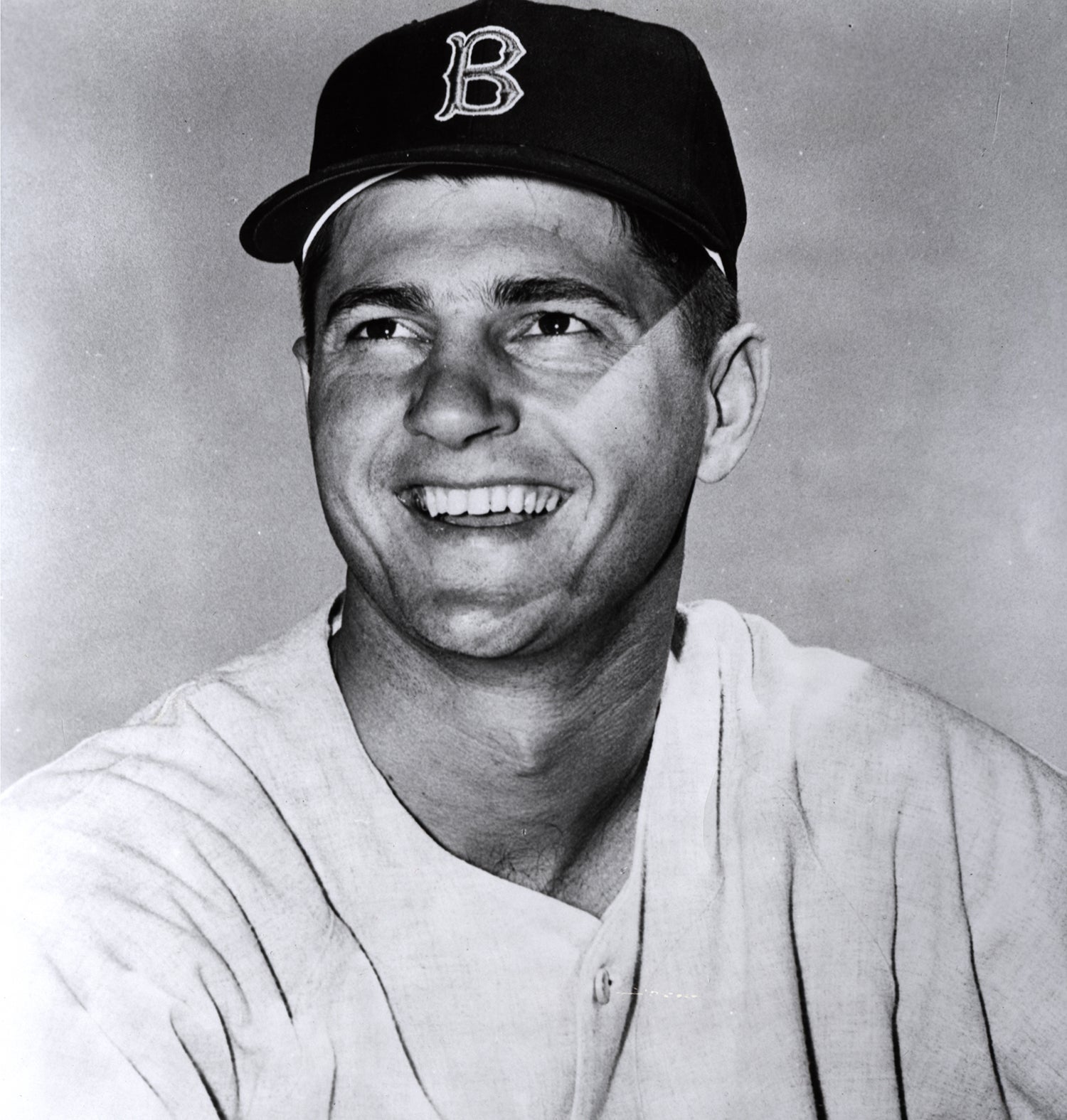

George Scott began his career with the Boston Red Sox in 1966 and stayed through the 1971 season. He would return to Boston in 1977 and would remain with the team until 1979, when he was traded to the Kansas City Royals. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

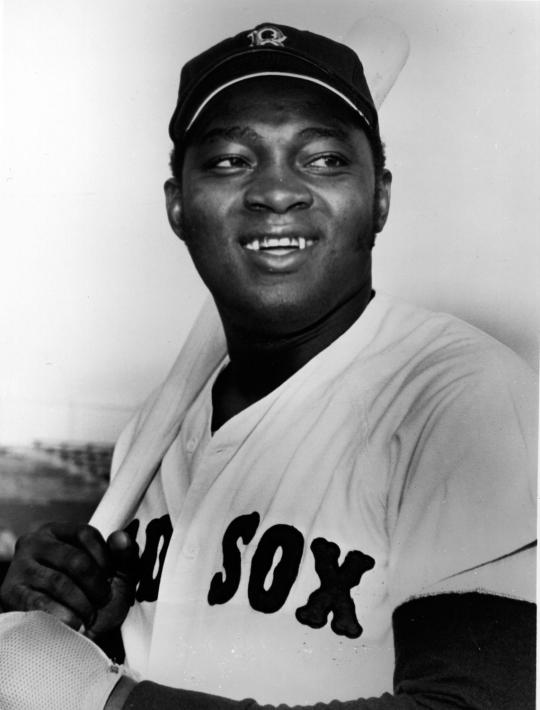

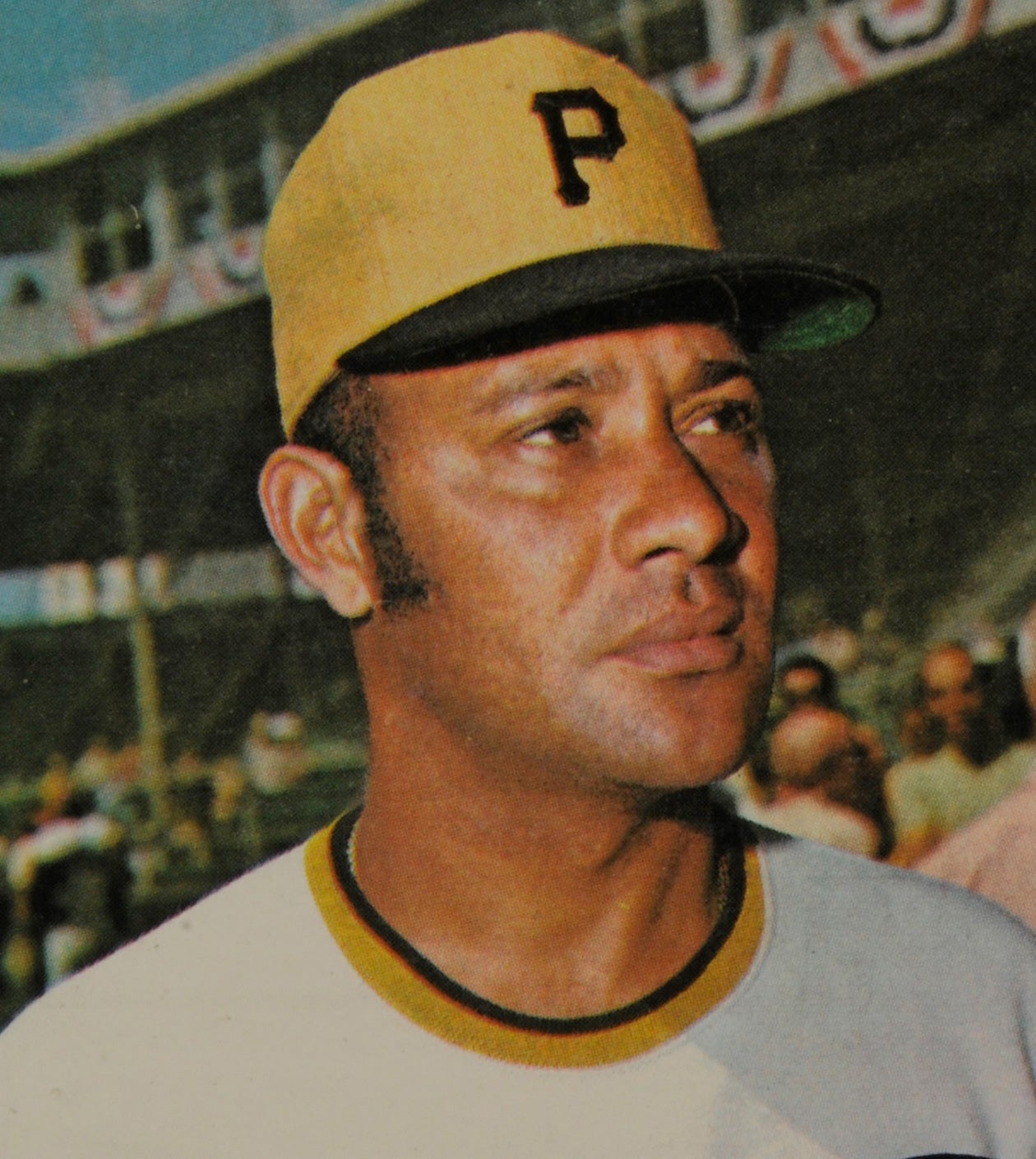

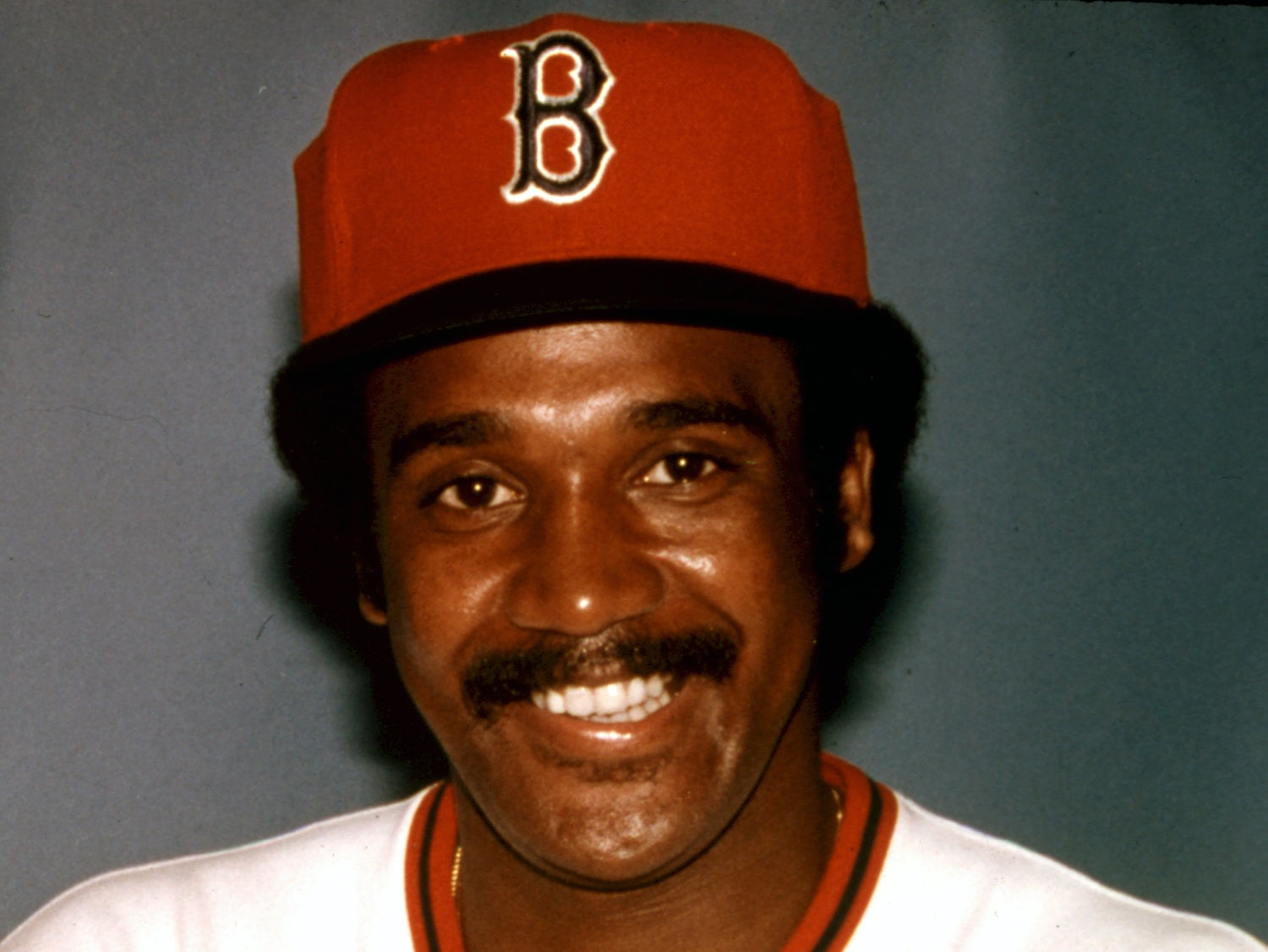

Joe Foy (pictured above) was a Red Sox teammate of George Scott's and came up with Scott’s nickname “Boomer.” (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

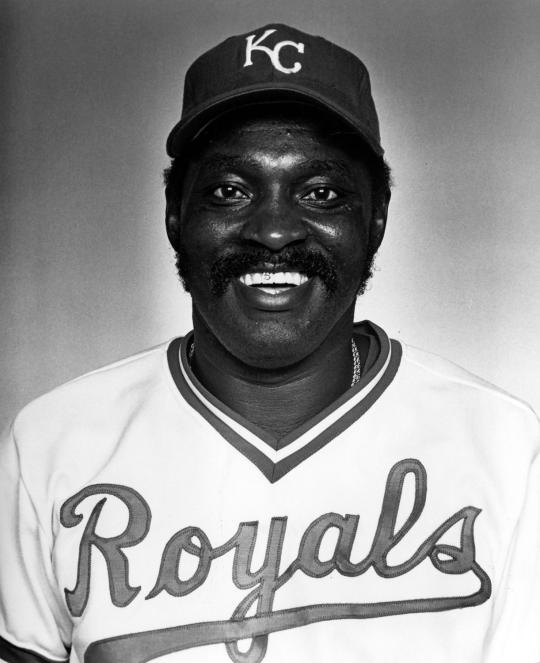

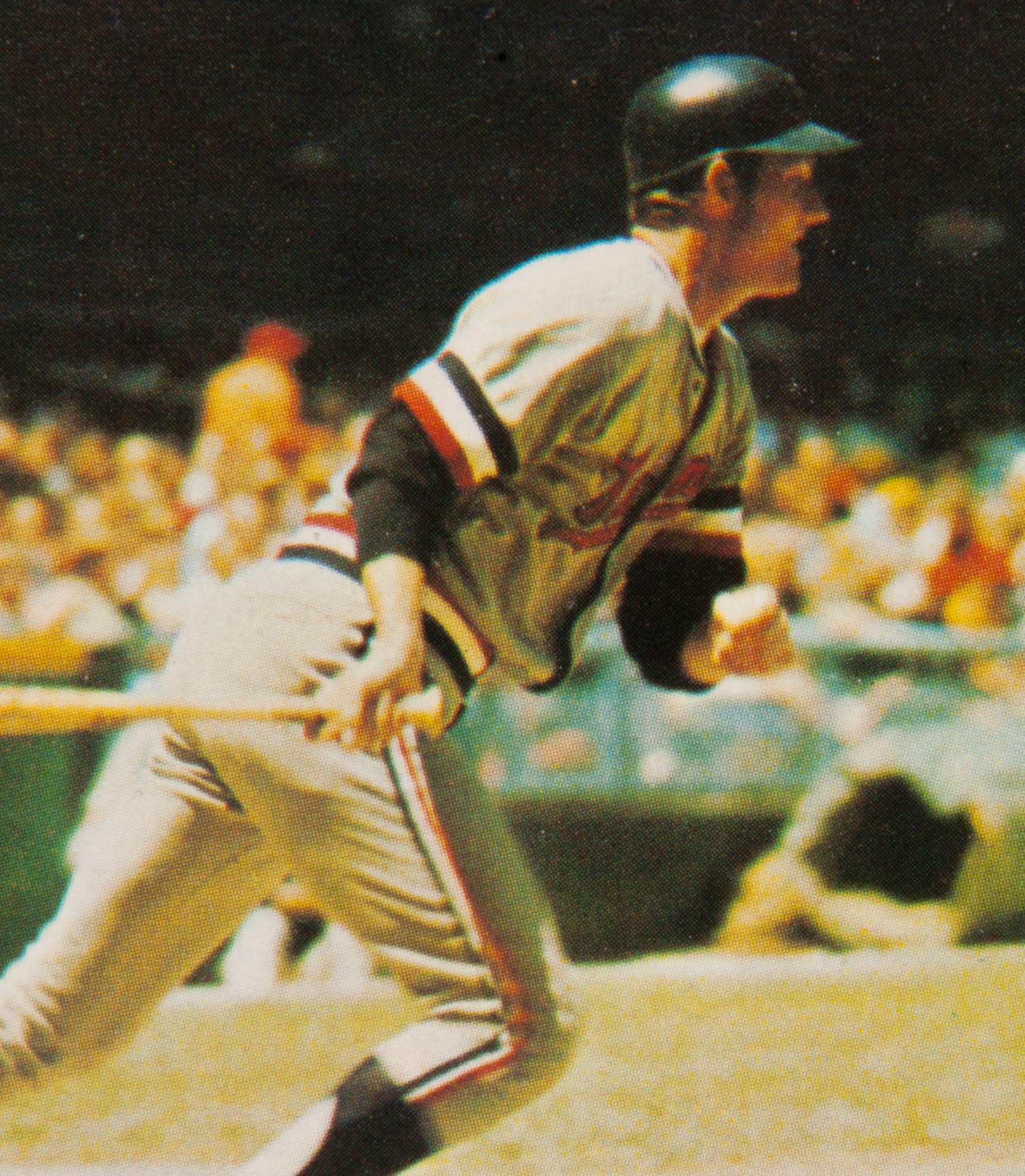

Over his four seasons with the Brewers, George Scott emerged as a star in Milwaukee, while also becoming extraordinarily popular with the fan base. (Doug McWilliams/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

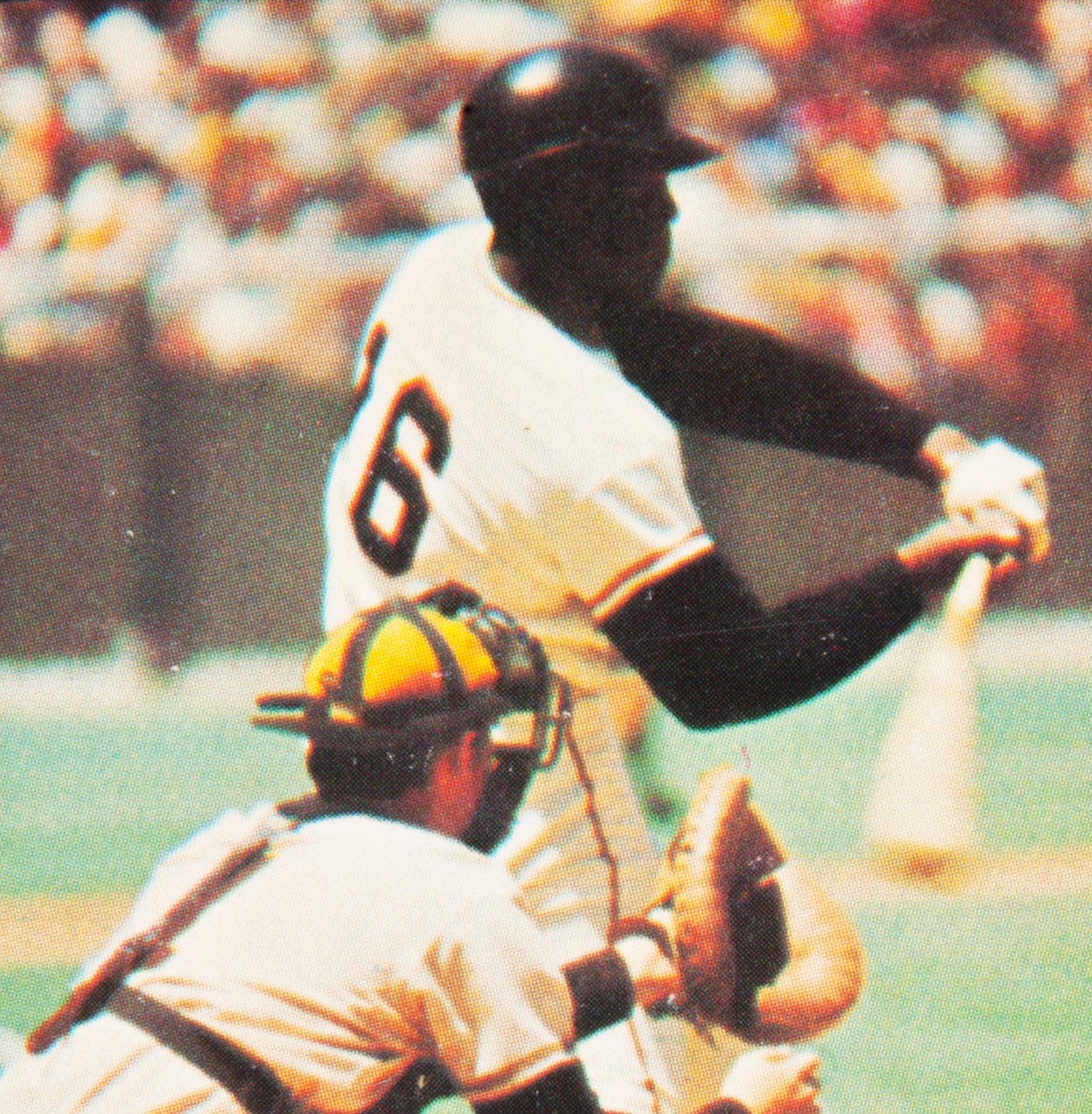

In 1977, George Scott (pictured in the top row, far left) returned to the Boston Red Sox, the team he began his career with in 1966. Above, he is pictured alongside his teammates in 1978 (from top left): Rick Burleson, Jim Rice, Carl Yastzremski, and from bottom left, Carlton Fisk, Fred Lynn and Bill Campbell. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In 1975, Scott’s game reached its peak. Reaching career highs with 36 home runs and a league-leading 109 RBIs, Scott also led the league in total bases. All things considered, Scott had become as feared as any right-handed hitter in the American League.

Scott’s dominant level of play started to abate in 1976. His OPS fell by over 100 points, dropping from .857 to .748. At one point, Brewers manager Alex Grammas dropped him to sixth in the batting order. Adding to the tension, general manager Jim Baumer placed much of the blame for the Brewers’ disappointing season on Scott. Not appreciating the lack of support from management, Scott requested a trade. At the December Winter Meetings, the Brewers obliged. They traded him and colorful outfielder Bernie Carbo to the Red Sox for a younger first baseman in Cecil Cooper.

Scott received a warm welcome upon his return to the Red Sox. He also enjoyed a resurgence at the plate, hitting 33 home runs and slugging .500. Enormously popular in Boston, Scott had a happy homecoming with the Red Sox. The addition of Scott to a lineup that already included Carl Yastrzemski, Jim Rice and Fred Lynn helped the Red Sox win 97 games, finishing a strong second to the New York Yankees.

Scott’s return to Boston increased his national exposure as one of the game’s colorful characters. Scott would talk to anyone, writers and fans alike, and regale them with humorous stories and one-liners. When a reporter asked him about the strange necklace of shells and beads that he wore around his neck, Scott responded that the accessory was actually made from “second basemen’s teeth.” That answer became a hit with the national media.

Scott also developed his own terminology. He liked to refer to home runs as “taters.” The term caught on with other players, including Reggie Jackson. Scott also came up with a nickname for his oversized first baseman’s mitt, fondly calling it “Black Beauty.” Scott also made for quite the sight at Fenway Park. Prior to games, he could be seen doing his pregame workout while wearing a rubberized sweatsuit, part of an effort to lose weight. By the end of the workout, Scott was dripping in perspiration. Yet, the regimen did not seem to help. By season’s end, Scott remained overweight, his large waistline still stretching polyester to its breaking point.

By 1978, Scott started to slow down for good. He hit only 12 home runs, missed a number of games with injuries and slogged his way through a poor second half, coinciding with the Red Sox’s collapse in August and September. After allowing a 14-game lead to evaporate, the Sox lost a memorable tiebreaker to the Yankees at Fenway Park.

Scott’s play did not improve in 1979. A slump in April and May dragged into June. And then on June 13, just two days before the trading deadline, the Red Sox parted ways. They sent Scott to the Kansas City Royals for outfielder Tom Poquette.

It was a puzzling move by the Royals. Scott’s game, built on hitting home runs, did not fit well at Kauffman Stadium, which featured long outfield dimensions and a fast, artificial turf surface. Scott hit only one home run in 146 at-bats, the lack of power leading to his release in August.

Nine days later, Scott found work with an unexpected source: The New York Yankees. Playing out the string of a disappointing season, the Yankees used Scott at first base and DH. He hit well, putting up an OPS of .840 in 16 games. With his bat suddenly looking live, rumors circulated that the Yankees might bring Scott back for the 1980 season.

For whatever reason, the late-season audition did not convince the Yankees. That winter, the Yankees signed another right-handed slugger, Bob Watson, as a free agent, making Scott expendable. When no other teams came calling, Scott took his services to the Mexican League, where he put up huge offensive numbers in 1981 and ’82. He later became a player/manager, eventually transitioning to fulltime managing in the independent minor leagues. He managed for several teams, including the Massachusetts Mad Dogs, before stepping aside in 2002.

In his later years, Scott put on an enormous amount of weight. At one point, he weighed over 400 pounds, which contributed to a series of health problems, including diabetes. In 2013, Scott’s body gave out, as he passed away at the age of 69.

Scott’s death brought a special sadness to a generation of fans, including this writer, who remembered watching him play. Scott was a singular player; no one looked like him and no one played like him. Whether it was wearing a helmet in the field, or that necklace made of second basemen’s teeth, or his fun-loving flair in talking about “taters,” George “Boomer” Scott gave us one wonderful memory after another.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum