- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Bob Locker

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Bob Locker

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

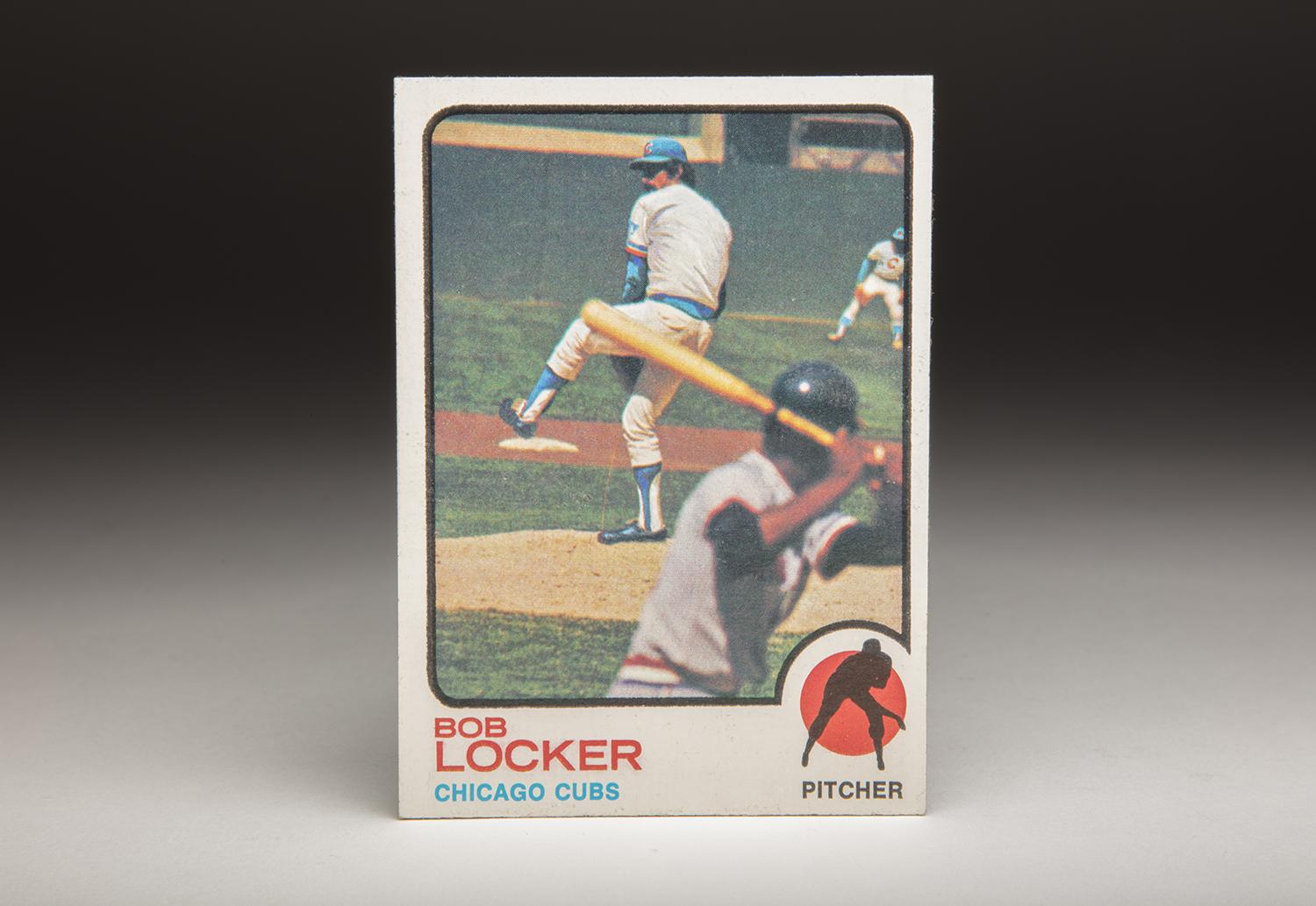

An entire book could be written about weird and peculiar baseball cards. If such a book were to make it to print, it would simply have to include Bob Locker’s surreal 1973 Topps card.

A first glance at Locker’s card reveals an obvious case of airbrushing. The home white and blue colors of the Chicago Cubs have been layered on to an existing photo that shows Locker pitching for the Oakland A’s in a 1972 game. We figure that it must be 1972, since the A’s used sleeveless vest uniforms in 1970 and ’71, which would have made it more difficult to airbrush the Cubs’ uniform onto a photo from one of those seasons. In 1972, the A’s switched to a pullover jersey featuring sleeves, making it easier to make the transition to the Cubs’ look. Since this is an action shot, something that Topps featured prominently in its 1973 set, Topps also had to airbrush Cubs colors onto the center fielder in the picture. That outfielder just so happens to be Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson.

Yet, the presence of Cubs colors onto Locker’s uniform is not what is most noteworthy about this card. What is notable is the lack of Cubs pinstripes from the airbrushed uniform. I’m guessing that it would have been exceedingly difficult to draw minute pinstripes onto Locker, so Topps decided not to even try.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Even more unusual is the complete absence of a number on the back of Locker’s jersey. With Locker’s back twisted to face the batter almost directly, we clearly see that he has no number, making for an odd appearance. For some reason, Topps decided not to airbrush the number in the color of the Cubs’ traditional blue. Rather than stay with a mismatched green number on the Cubs’ blue and white uniform, Topps simply chose to obliterate the number, leaving us with a numberless jersey. In a way, it’s a throwback to the days from the early part of the 20th century, before the Cleveland Indians and the New York Yankees became the first clubs to permanently add numbers to the backs of their players’ jerseys.

In trying to dissect this card further, I became determined to pin down further details about the card. Where was this photograph taken? Based on the fact that the batter is wearing a road gray uniform, the A’s must be the home team. It has to be a shot from the Oakland Coliseum, where Topps photographers took many of their pictures during the 1970s. (That group of photogs included the great Doug McWilliams, whom we have profiled in past editions of Card Corner) The next questions involves the identity of the opposition team in the photograph. Who were the A’s playing on this sun-soaked day at the Oakland Coliseum in 1972? For that, let’s enlist the help of the Hall of Fame’s skilled Curatorial Department.

Initially, I thought that the batter facing Locker was wearing the road uniform of either the Baltimore Orioles or the Minnesota Twins. Curator of History and Research John Odell immediately ruled out the Orioles, explaining that Baltimore’s road uniforms featured orange on the bottom of the waistband and black on the top of the waistband. Clearly, the player in the photograph has a waistband with the colors in reverse: orange on the top and black on the bottom. So it can’t be a player with the Orioles.

John then offered some speculation that the player might be a member of the Texas Rangers. Senior Curator Tom Shieber, an expert on baseball uniforms, confirmed that the waistband of the photo matches the waistband the Rangers used in 1972.

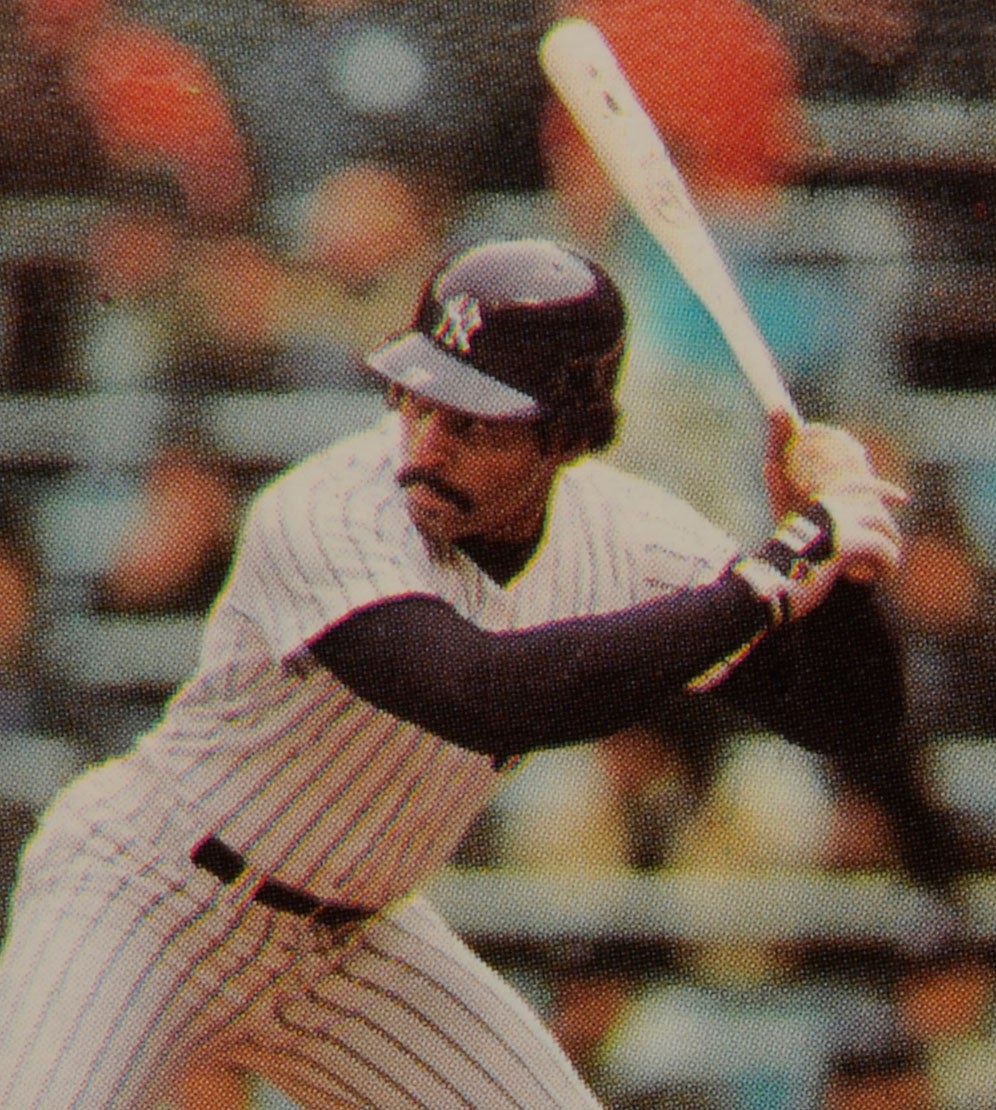

Tom then took it a step further, trying to determine players on the Rangers who batted right and happened to be African American, like the player in the picture. Tom came up with four possibilities: infielders Dave Nelson and Tom Ragland, and outfielders Ted Ford and Elliott Maddox. (Two other members of the Rangers, the switch-hitting Vic Harris and Lenny Randle, also had the ability to bat right-handed, but they would have batted left-handed against the right-handed throwing Locker. Based on that logic, we can rule out Harris and Randle.)

Not satisfied to narrow the list to a final four, Tom continued to research the matter. He determined that Locker faced the Rangers in two games at the Oakland Coliseum during the 1972 season. They happened to be in both ends of the same doubleheader, occurring on July 30. That was the same day that Topps photographed Nelson for his 1973 Topps card, lending further credence that the Locker photo was taken that same day. And by the way, Reggie Jackson played center field in both games, confirming that he is the airbrushed player in the background of the photo.

In the first game of the doubleheader, Locker faced only one batter, the aforementioned Maddox, whom he struck out. So it could be Maddox. In the nightcap, Locker faced only one of the four players mentioned above, Nelson, whom he struck out for the final out of the game. So it could be Nelson, or it could be Maddox. Based on a visual scan, I would guess that it is Maddox, who had a long, lean build that seems to fit the player on the card, but that’s strictly a guess on my part.

Now that we’ve unlocked the mysteries of this card, let’s begin to unlock Locker, who was a very good relief pitcher with a reputation for a high level of intelligence. Locker’s pro career began in 1960, when he signed with the Chicago White Sox. Locker received a higher monetary offer from the New York Yankees, but he opted for the White Sox because he felt they offered a shorter path to the major leagues. Five years later, Locker found the end of that path, making his debut for the Sox in 1965. In between, he managed to obtain a college degree in geology. He also missed two full years of baseball while fulfilling an obligation to the ROTC.

In the spring of ’65, Locker made the Sox’ Opening Day roster. By then, he was already married with children, and had put in his two years of military time. He also prided himself on physical fitness. That spring, Locker drew snickers from his veteran teammates by wearing a 10-pound weighted canvas vest that looked like a bullet-proof jacket used by members of a SWAT team. When Chicago reporters asked him about the vest, Locker offered some unconventional logic that was a little hard to follow, but ultimately made some sense. “You see,” Locker told Edgar Munzel of the Sporting News, “most of the players come to camp about 10 pounds overweight, while I never gain an ounce. The fellows with the extra weight are strengthening their legs just carrying it around during these workouts before they finally take it off. Since I never am overweight, I saddle myself with those extra pounds to put me even with them.”

Locker’s unusual preparations also involved the way that he approached opposing hitters. He carried around with him a large set of index cards, which provided information on hitters and umpires. Locker wanted to know the strength, weaknesses, and tendencies of every batter and umpire in the American League.

As a minor leaguer, Locker had worked as a starter, but the White Sox put him in the bullpen. They told him to ditch his other pitches and throw his sinking fastball almost exclusively. At one point, manager Eddie Stanky threatened Locker with a fine if he gave up a hit on any pitcher other than a sinker. Locker himself compared his sinker to a knuckleball, because of its unpredictable pattern of movement. At times, Locker’s sinker was a devastating pitch.

Right from the start, Locker proved effective in middle relief. By 1966, he moved into a late-inning role, sharing the closer’s role with Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm and veteran reliever Eddie Fisher. In 1967, he became a workhorse, leading the American League with 77 appearances and logging a little more than 124 innings. He remained effective in 1968, when he appeared in another 70 games.

Then came the disaster of 1969. In April and May, Locker lost his feel for the sinker, and saw his ERA rise over 7.00. Concerned that Locker might be hurt, or simply was over-the-hill at the age of 31, the White Sox impatiently traded him on June 8, sending him to the expansion Seattle Pilots for journeyman right-hander Gary Bell.

With the Pilots, Locker felt right at home. In Chicago, he had developed poor pitching mechanics, a problem that he would alleviate in Seattle. He also became friends with two other relievers, Jim Bouton and Mike Marshall, both of whom were known as independent thinkers and highly intelligent men. A player who liked to read and spend time in deep thought, Locker found two like-minded individuals in Bouton and Marshall.

Locker pitched well for the Pilots, but changes followed in 1970. The Pilots relocated to Milwaukee, where Dave Bristol stepped in as the new manager. Bristol changed Locker’s role, reducing him to mop-up man status. In midsummer, the Brewers sold Locker, practically giving him away to the A’s for a small sum of cash.

With the A’s, Locker would continue to cement his reputation as a unique character, one who had habits far different than most of his teammates. Locker avidly followed the philosophies professed in the 1970 bestselling book, Jonathan Livingston Seagull. Locker encouraged his A’s teammates to read the book, a fable about a seagull learning to live, and make it a model for their own way of life.

Locker would also become active with the Players Association, where he greatly admired the leadership provided by Marvin Miller, the onetime representative for the U.S. Steelworkers. “He was one of the most soft spoken, yet insightful people, I had ever met,” Locker once said, “and [he] was willing to sacrifice his position with the Steelworkers to take on a difficult task for the players.”

On the field with the A’s, Locker would achieve the greatest fame of his career. At first, he served the A’s as a set-up man to relief ace Mudcat Grant, before performing the same role for Hall of Famer Rollie Fingers. Locker’s ability to throw strikes and keep the ball down made him a reliable pitcher in the late innings, one whom manager Dick Williams turned to again and again.

Locker was never better for the A’s than in 1972. Pitching 78 innings, Locker posted an ERA of 2.65 and even saved 10 games on days when Fingers needed a rest. With Fingers and Locker and left-hander Darold Knowles leading the charge, the A’s had one of the game’s best bullpens – a major factor in the team winning the American League West title.

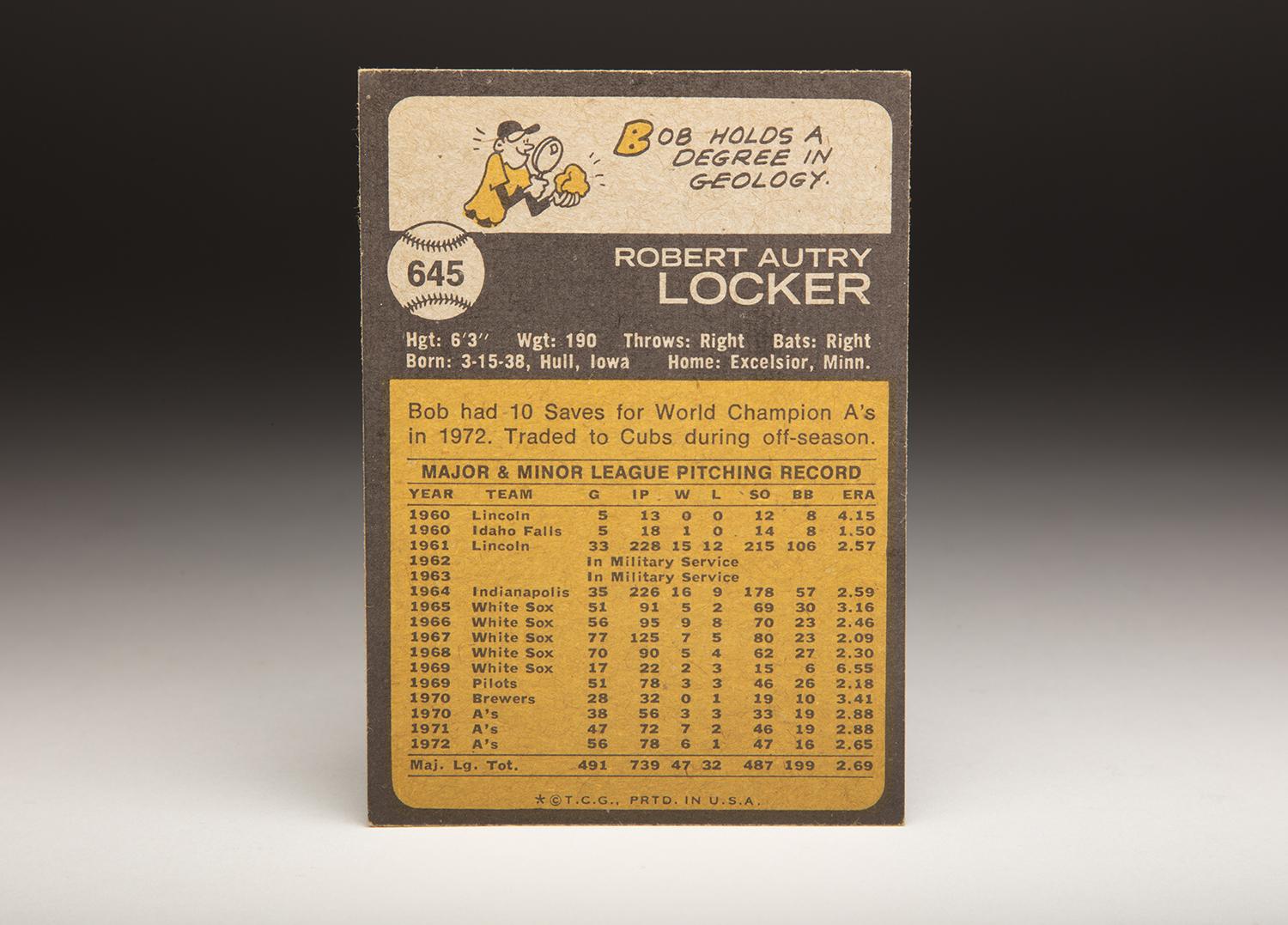

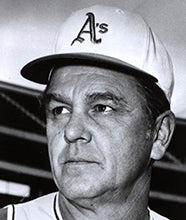

Eddie Stanky, pictured above, played for the St. Louis Cardinals for two seasons of his 11-year-long career. He became a big league manager after retiring, and was Bob Locker's skipper on the Chicago White Sox from 1966-68. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

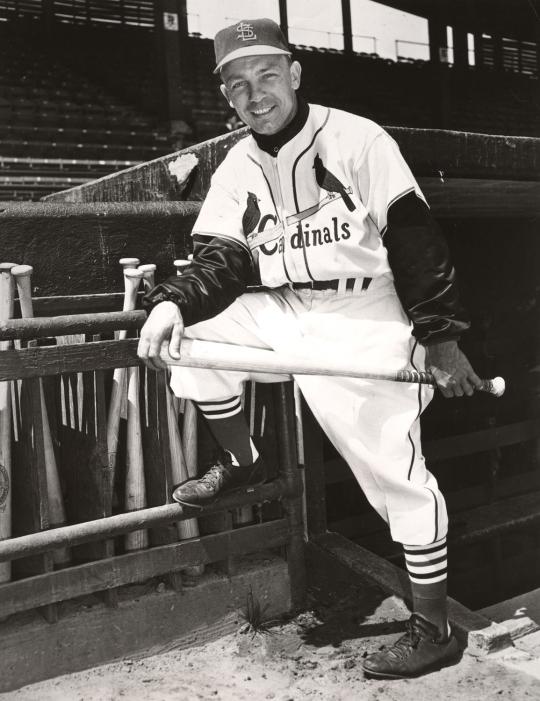

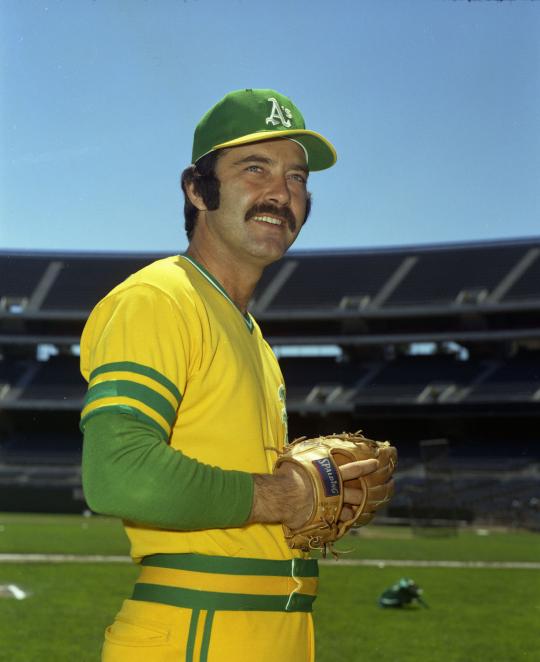

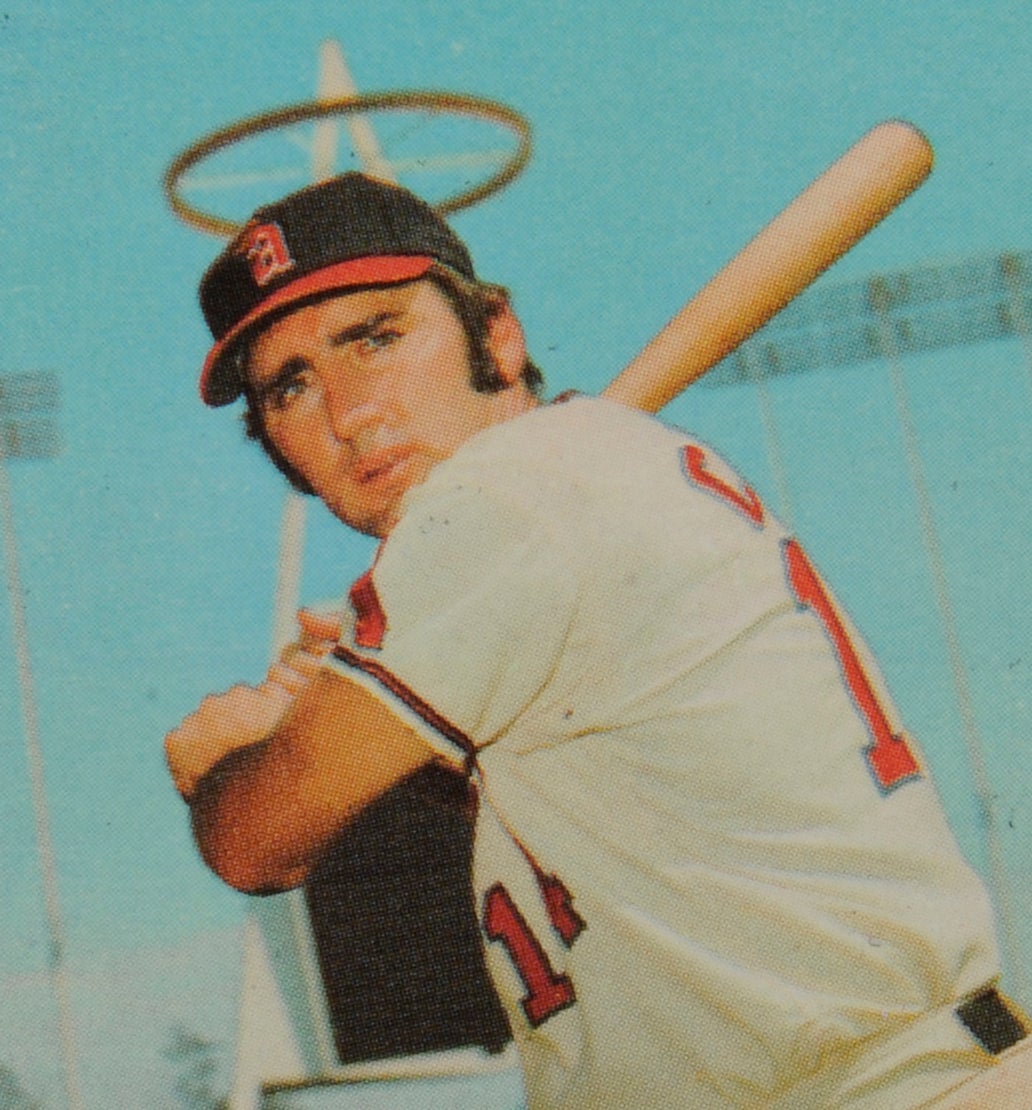

Bob Locker served as a set-up man for Athletics' relief ace Jim "Mudcat" Grant while he was in Oakland, and would later do the same for Hall of Famer Rollie Fingers. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

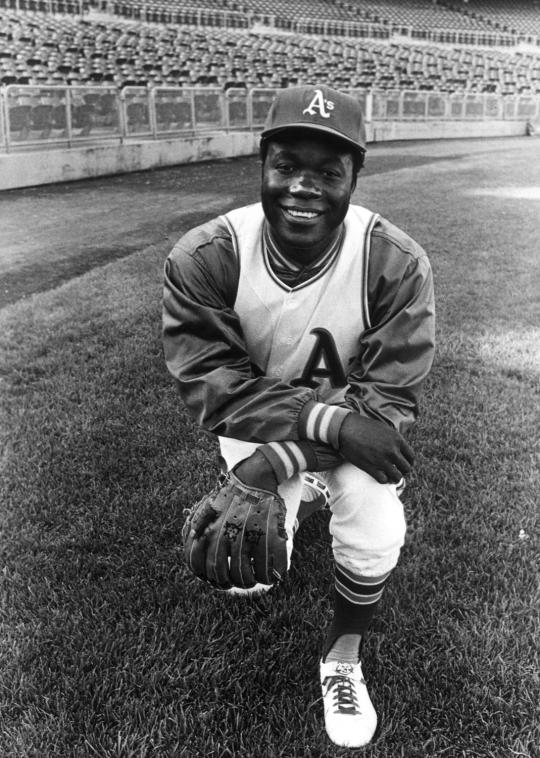

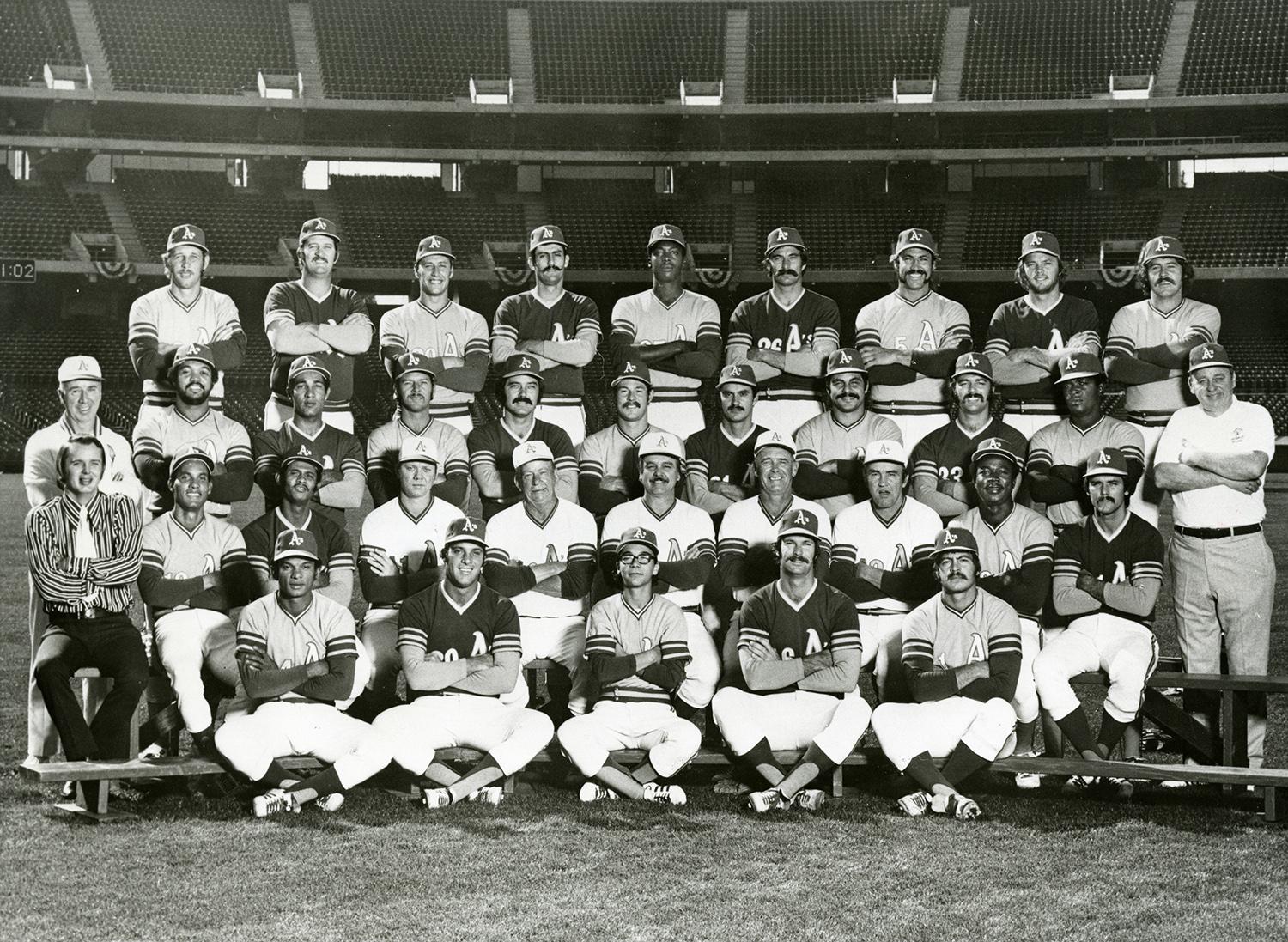

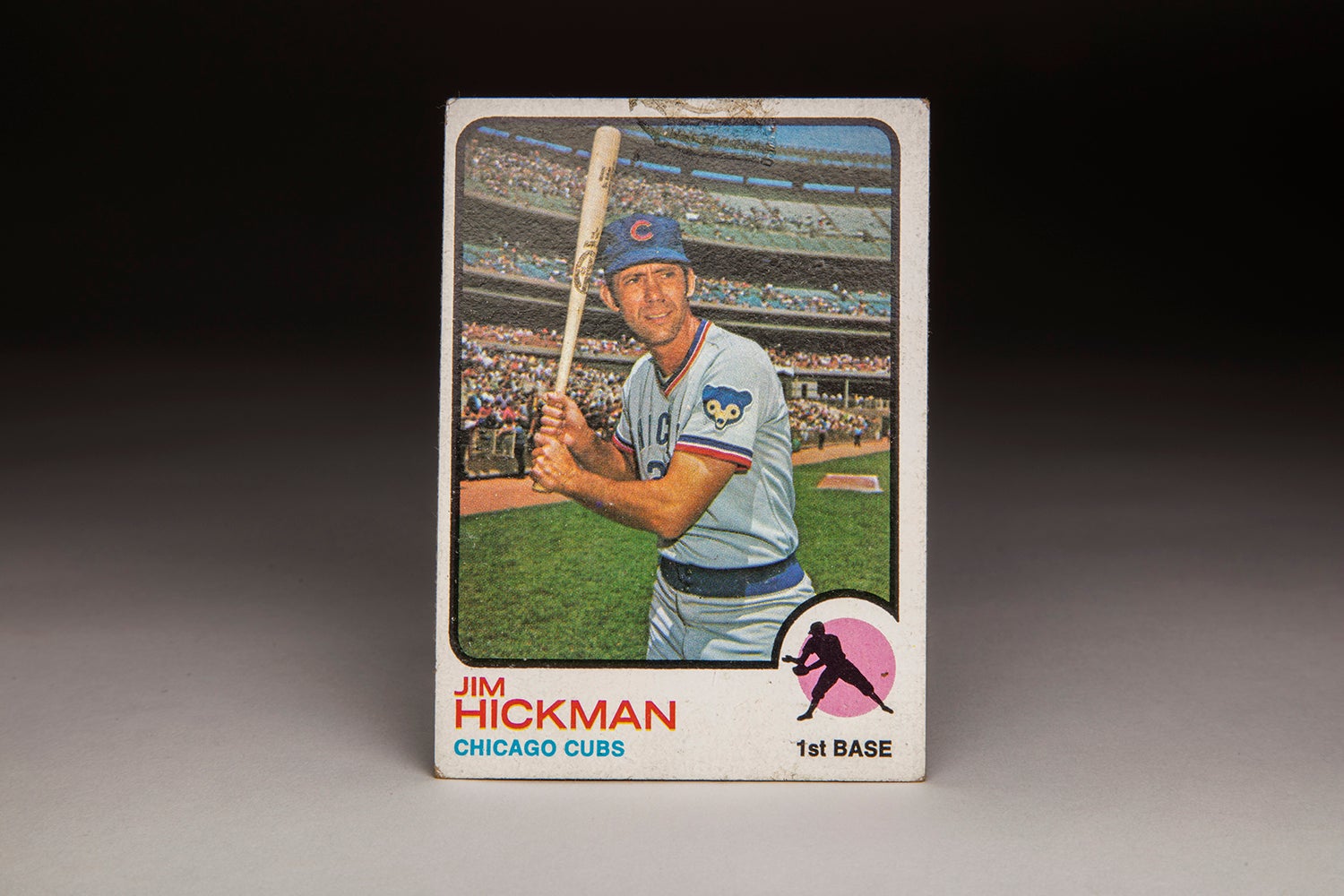

With Hall of Famer Rollie Fingers, Bob Locker and Darold Knowles (pictured above), the 1972 Oakland A's had one of the best bullpens in baseball. (Doug McWilliams / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

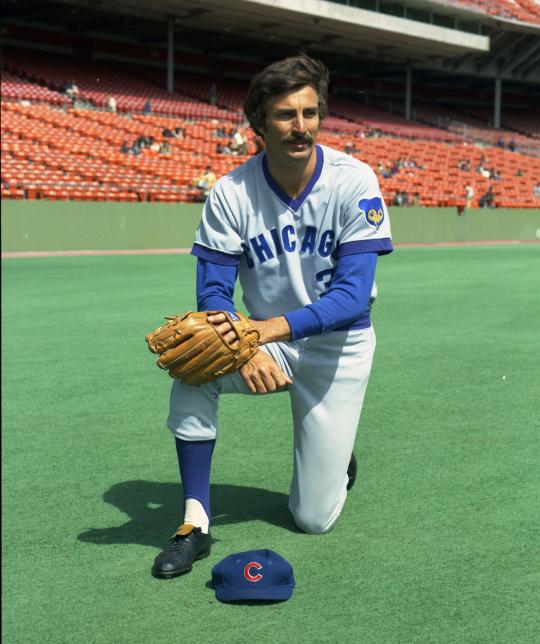

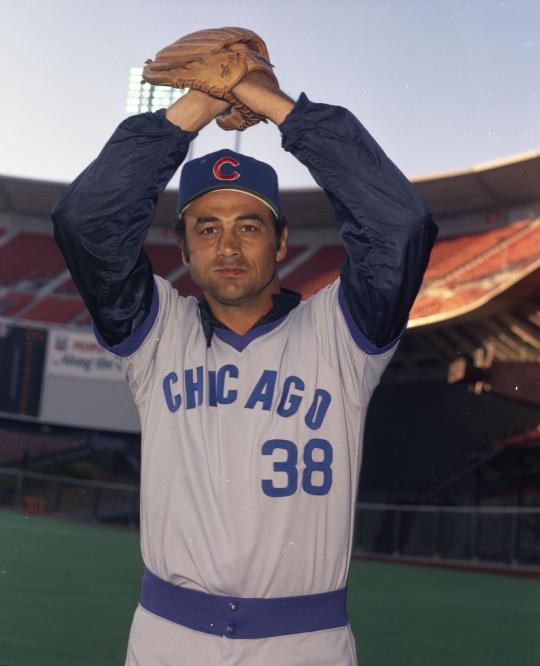

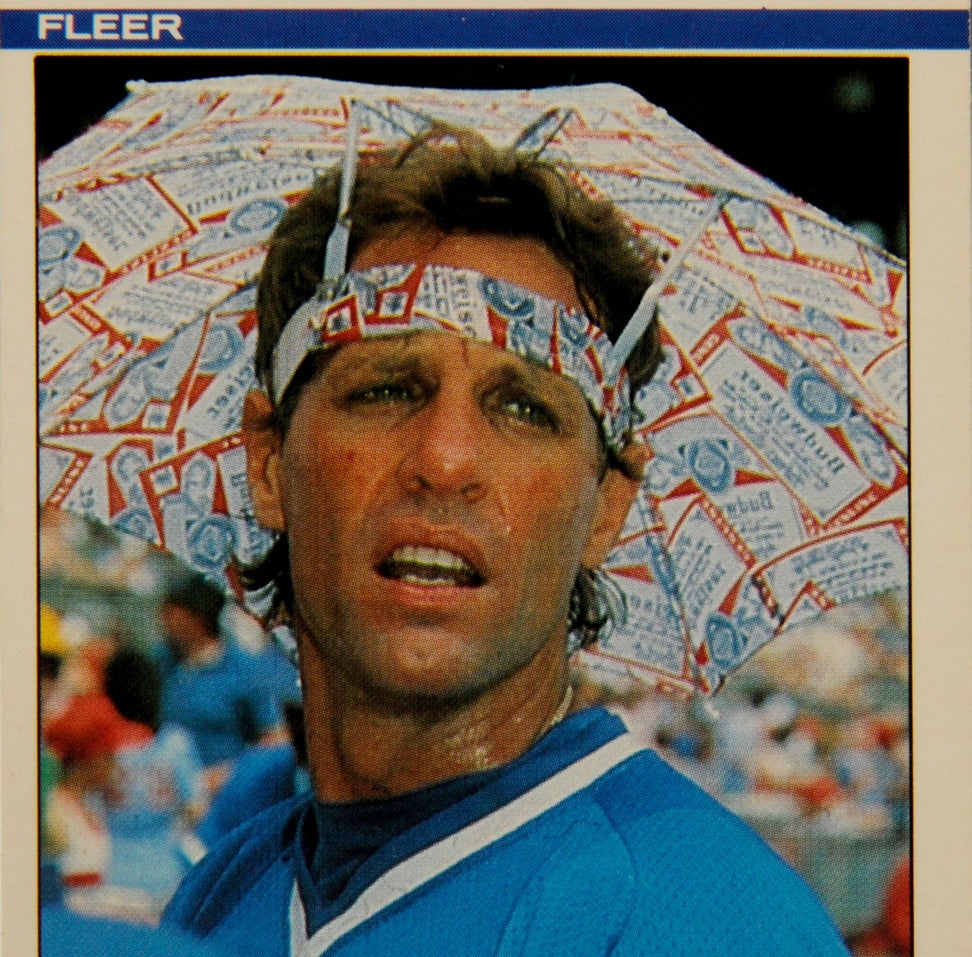

Bob Locker played on the Chicago Cubs in 1973 and 1975. (Doug McWilliams / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Locker would struggle in the Championship Series against the Detroit Tigers, but the A’s still managed to advance to the World Series. Appearing in one Fall Classic game, Locker logged a scoreless third of an inning, as the A’s won their first Series title since their move to Oakland.

As well as Locker pitched for the A’s in 1972, he was now 34 years old and part of a deep bullpen. Believing that they could trade from that depth, the A’s sent Locker to the Cubs in a wintertime deal for young center fielder Billy North. The trade allowed Locker to return to his original major league city, but now with the National League Cubs. Initially, Locker wanted no part of the trade. He liked playing for the A’s and enjoyed making his home in the Bay Area. He threatened to quit the game outright, rather than report to the Cubs’ camp in Arizona.

Thankfully, Locker changed his mind. He reported to Spring Training, but quickly came down with a sore arm. “My arm was so weak I couldn’t break a pane of glass,” Locker told famed Chicago sportswriter Jerome Holtzman. Working through the pain, Locker’s armed bounced back. He pitched beautifully in his second Windy City go-round, becoming a late-inning workhorse for manager Whitey Lockman. He also added a change-up to his repertoire, a pitch that prevented teams from keying in on his sinker. Accumulating 106 innings, the veteran righty sported an ERA of 2.54 and saved 18 games while wresting away the closer’s role from Jack Aker.

Although Locker had shined for the Cubs, he asked the team to trade him back to Oakland, so that he could be near his home in the Bay Area. On Nov. 3, the Cubs obliged, sending him back to the A’s for sidearming reliever Horacio Pina. But Locker would never appear in another game for Oakland. The heavy workload of 1973 took a toll on Locker’s right arm. He came down with a bad elbow, necessitating surgery. As a result, he missed all of the 1974 season.

After the lost summer of ‘74, the A’s sent him back to Chicago yet again as part of a deal for Hall of Famer Billy Williams. Locker reported to Spring Training in 1975, his elbow feeling fine, but his shoulder now hurting. Locker struggled in April and May, as he issued more walks than he collected strikeouts. In late June, the Cubs released Locker, ending his long career.

Locker left the game with a 2.75 ERA, 95 saves, and a total of 879 innings. He also became a rarity for his era – a pitcher who never made a single career start, his 576 appearances all coming out of the bullpen. In an era before specialists, Locker was exactly that – and a good one.

Choosing not to remain in baseball, Locker settled in to life in the Bay Area, where he lived with his wife and worked in real estate and exterior design for nearly three decades. In the early 2000s, he retired to Montana, where he became an inventor and writer. Locker essentially taught himself how to write professionally, without the benefit of formal training. To date, he has published three books, including Cows Vote Too and Esteem Yourself. The latter is a volume meant to inspire young people. Clearly, the books have nothing to do with baseball.

A man of many talents and supreme intelligence, Locker has led a life that is anything but typical of a major league ballplayer. It’s been an unconventional life for the man who, most fittingly, starred on one of the strangest baseball cards ever made.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum