- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Mike Epstein

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Mike Epstein

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

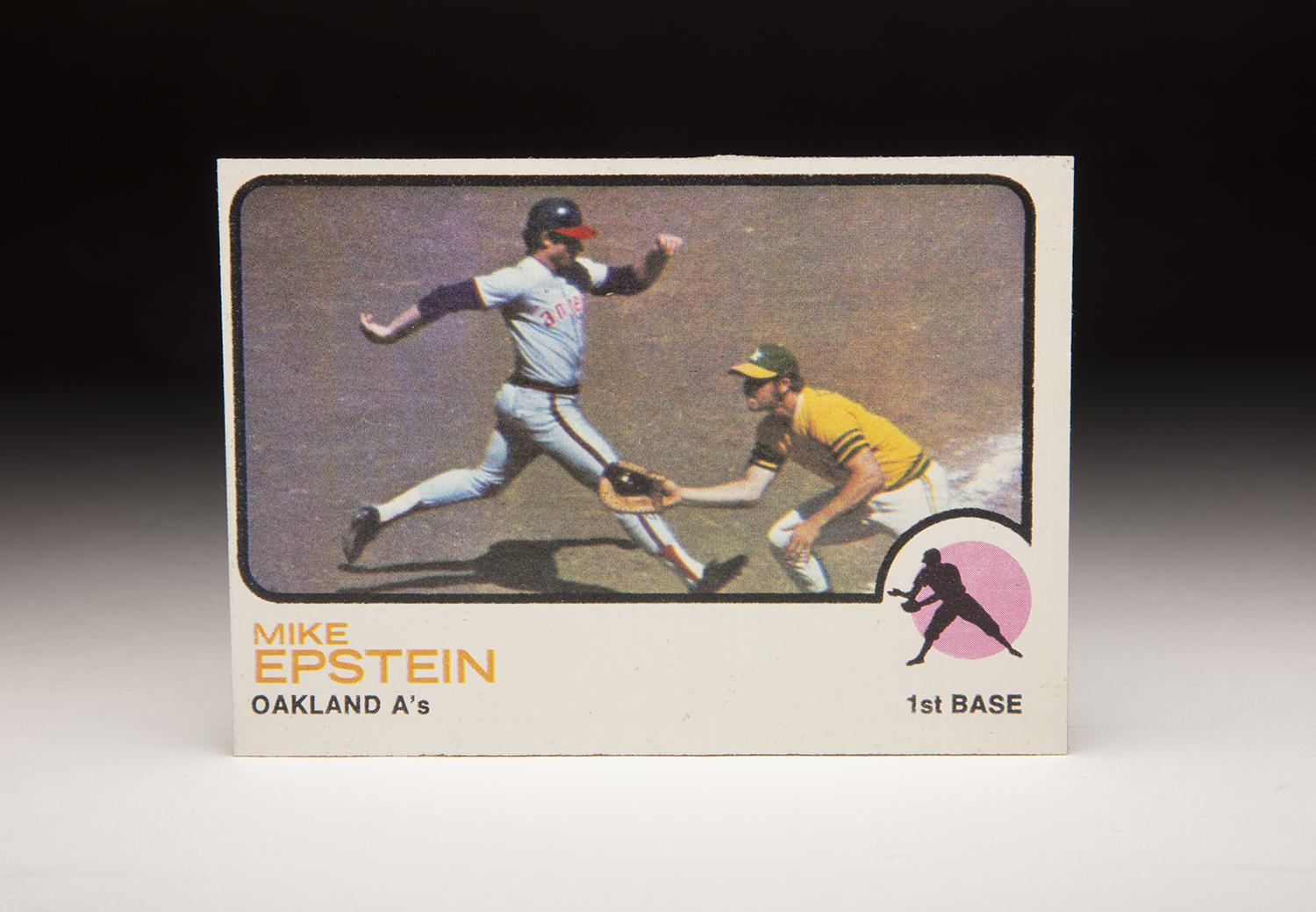

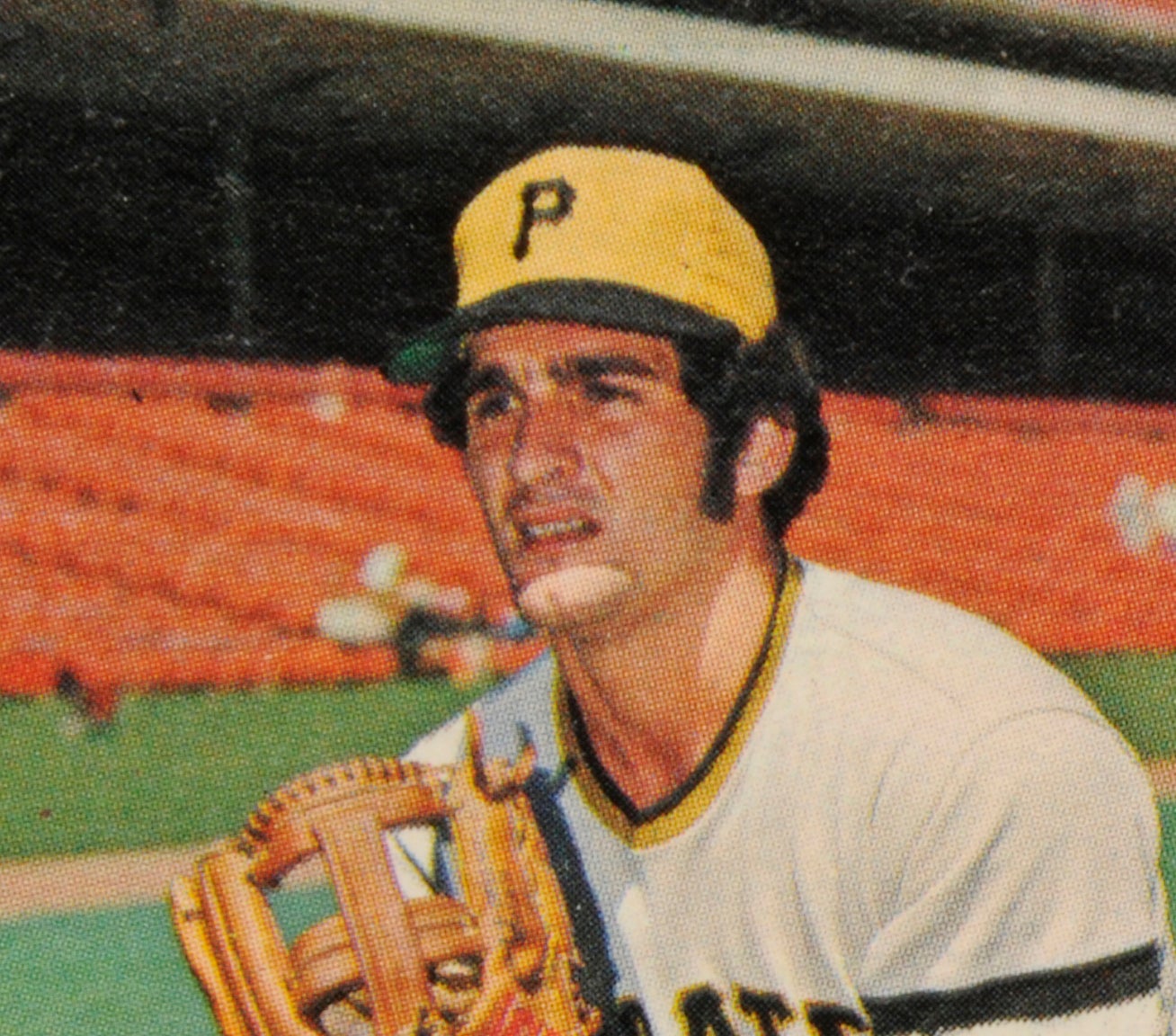

Every once in a while, I will see an action card that is framed so well that it appears almost poetic. That’s long been my reaction to Mike Epstein’s 1973 Topps card.

With his glove hand extended outward, Epstein is waiting for a throw, hoping to nab an anonymous runner for the California Angels. The baserunner, seen in the midst of making a very long stride toward first base, is extending both of his arms in such an exaggerated fashion, with his right wrist curled, that it looks like he’s executing an elaborate dance step. He is almost swanlike in his baserunning style.

I first saw this card back in 1973, when it was originally released by Topps. For years, I had assumed that the unknown Angels player was running between home plate and first base, trying to beat out an infield grounder or maybe even a bunt. Upon further review, I realized that I was wrong. The position of the first base line, which is behind Epstein, tells us that the runner is actually hung up between first base and second base, and not home plate and first. Perhaps he rounded the first base bag too hard, or maybe he’s returning to first base after a fly ball has been caught in the outfield.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

That situation solved, there is still some mystery surrounding the card. Who is the Angels’ baserunner? Since Epstein did not play for the A’s in 1973, and the A’s changed their uniforms after the 1971 campaign, we know that the photograph had to be taken during the 1972 season. That allows us to narrow the list of candidates. The runner is Caucasian, so that rules out the African-American and Latino players on the Angels, including Sandy Alomar, Bob Oliver, Leo Cardenas, Vada Pinson, Mickey Rivers, and Leroy Stanton. That still leaves us with several possibilities, including one of the following: Jeff Torborg, Art Kusnyer, Jim Spencer, Ken McMullen, Ken Berry and Andy Kosco. It’s also possible that it could be one of the Angels’ pitchers; after all, the DH rule did not come into play until 1973.

In this day and age, when one needs an answer fast, the search goes to the Internet. I found two different articles that stated the runner to be Spencer, the Angels’ first baseman. Armed with that piece of information, I took another look at the card. At the time, Spencer was still relatively slim and wouldn’t put on significant weight in his midsection until his later years with the Chicago White Sox and New York Yankees. Spencer could be the player in question.

When I brought this up on a blog I was writing at the time, a couple of faithful readers claimed that I was wrong about Spencer. They believed the baserunner to be Ken Berry, the Angels’ slick-fielding center fielder, in part because the player’s sideburns on the card matched the sideburns of some photographs taken of Berry at the same time. With a slimmer frame, not to mention a habit of running with his wrist cocked, Berry seemed like a logical answer. I looked at the card again. Those readers appeared to be right. It looked more like Berry than it did Spencer.

That riddle answered, we can now turn to the primary subject of the card. There’s no question about his identity: It is Epstein, who was playing first base for the world champion Oakland A’s. The only mystery with Epstein had to do with his playing career, which started with so much promise. Yet he never quite became the superstar that scouts had envisioned. Furthermore, his career ended early and abruptly, making many fans and media members wonder what exactly happened.

Epstein’s professional career began in 1964, the year before the big leagues adopted the draft. A football star in college who decided to turn to baseball, Epstein considered offers from a number of teams, including the hometown New York Yankees. Some anticipated that the native of The Bronx would sign with the Yankees, who would have loved a talented young slugger of Jewish heritage. With its large Jewish population, New York seemed like the perfect place for Epstein. But Epstein instead chose the Baltimore Orioles, who outbid all of the other competitors and gave him a bonus of more than $20,000.

Epstein did not play the regular minor league season in 1964, but instead debuted in the Fall Instructional League. Despite his lack of experience, the Orioles thought enough of him to bring him to Spring Training in 1965. From the very beginning, Epstein made a distinct impression on the writers covering the Orioles, who noted his non-typical manner of speech. Giving in-depth, non-clichéd answers, he showed off a large vocabulary and a high IQ. During an interview with Baltimore writer Doug Brown, Epstein said the following: “As Emerson said, ‘Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm.’ ” In light of such quotes, Epstein was dubbed “Egghead.”

Prior to the end of camp, the Orioles assigned their highly intelligent slugger to Stockton of the Class A California League. Epstein hit 30 home runs and batted .338. Those numbers helped him win the league’s MVP Award. Epstein’s rookie performance also caught the attention of the managers in the California League, including the colorful Rocky Bridges. When asked about Epstein, Bridges called him “Superjew.” Epstein liked the nickname. Unlike Egghead, that nickname would stick with Epstein, both in baseball and beyond.

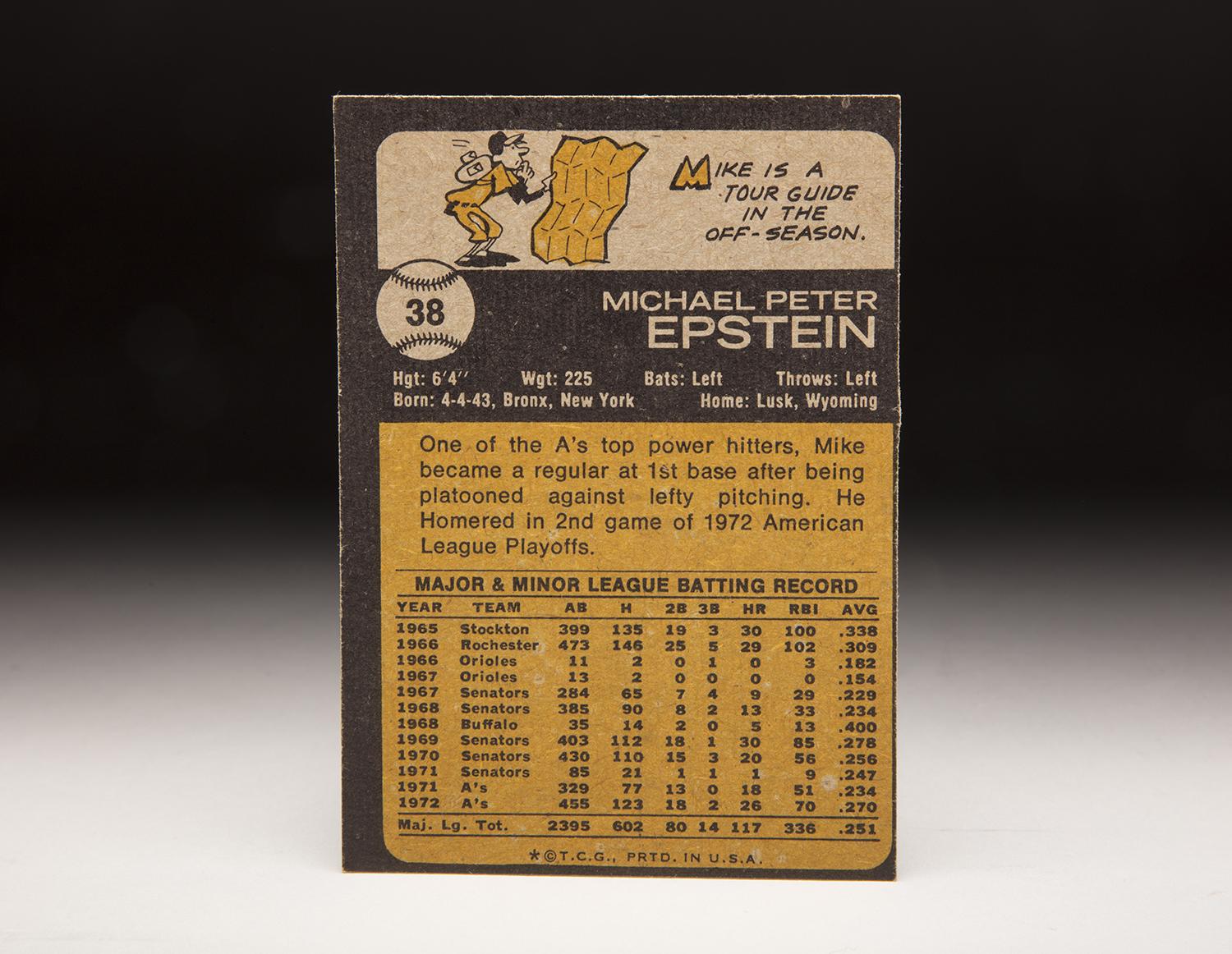

Duly impressed by their top slugging prospect, the Orioles decided to have Epstein bypass Double-A ball in 1966. They promoted him all the way to Triple-A, where he played for the Rochester Red Wings of the International League. Epstein adjusted easily to Triple-A competition. Epstein batted .309 and compiled an OPS of .999, so dominating the league that was he chosen as Minor League Player of the Year. At the end of Rochester’s season, Epstein made his way to Baltimore, where the Orioles gave him a six-game looksee in September.

It was obvious that Epstein had the talent to play in the major leagues. But the Orioles didn’t know exactly where to play him. A first baseman by trade, Epstein found himself blocked by another left-handed slugger, Boog Powell. That left the outfield as the other option, but Epstein had little experience there.

Epstein’s role became a point of contention during the spring of 1967. Veteran sportswriter Milton Gross approached Orioles manager Hank Bauer and asked him what he planned to do with Epstein. Bauer did not appreciate the inquiry. “How the hell do I know what I’m going to do with Epstein?” the gruff Bauer shouted at Gross. “That’s what we’re down here to find out.”

The O’s soon found out that Epstein had basic trouble catching fly balls, ruling out the outfield. Rumors circulated that the Orioles would have to trade Epstein. One report contended that he might be headed to the New York Yankees in a straight-up deal for ace righty Mel Stottlemyre.

The Orioles broke camp with Epstein on the Opening Day roster, but without a spot in the starting lineup. In the early going, Bauer used Epstein as a pinch-hitter and backup first baseman. After a few weeks, in which Epstein had appeared in only nine games, the Orioles decided that he would benefit from a return to Triple-A, where he could play every day. Epstein would have none of it. He refused to report, and told the Orioles that he had decided to leave the organization and head back to New York to live with his wife and grandmother.

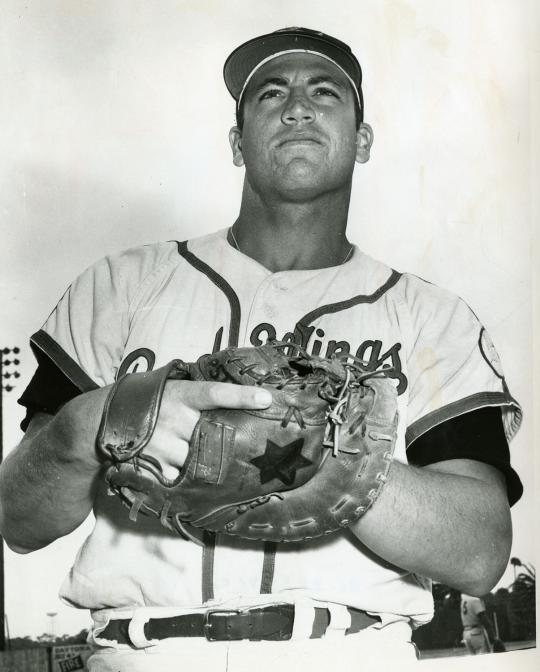

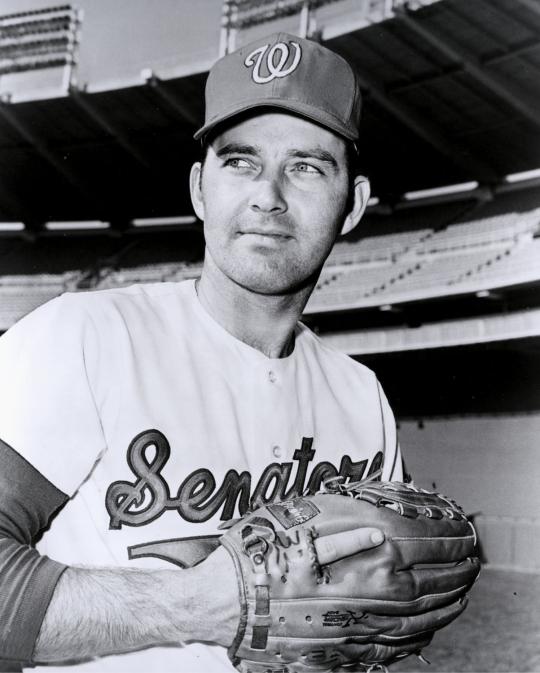

Orioles general manager Harry Dalton eventually resolved the situation by making a trade, not with the Yankees, but with the Washington Senators. He packaged Epstein with relief pitcher Frank Bertaina, sending them to Washington for lefty reliever Pete Richert. The trade provided Epstein with a much-needed change to his career. The Senators, with far less talent than the Orioles, needed help at first base. They also needed a left-handed power hitter. Senators manager Gil Hodges gladly made Epstein his starting first baseman while batting him in the middle of a lineup that featured mostly right-handed hitters.

Over the rest of the 1967 season, Epstein batted only .229. But he showed some long ball potential, hitting nine home runs. The Senators believed that Epstein would soon become a power-hitting star first baseman.

Reporting to training camp early in 1968, Epstein proceeded to lose 20 pounds, making himself leaner than at any other time in his professional career. Epstein looked and felt better, but his hitting did not improve. At one point, he was sent down to the International League. Throughout the season, he struggled badly against left-handed pitching. With a .219 batting average and a .333 slugging percentage against southpaws, Epstein became such a liability that Jim Lemon, the successor to Gil Hodges, began to platoon him. The circumstances of the Year of the Pitcher, with high mounds and an ever-expanding strike zone, did not help matters, either.

As they made preparations for the 1969 season, the Senators made a managerial change. They fired Lemon and replaced him with Hall of Famer Ted Williams. The switch to Williams, known as one of the best and most innovative hitting instructors on the planet, would prove highly beneficial to Epstein.

Williams believed in a scientific approach to hitting, one predicated on patience and a knowledge of the strike zone. Epstein embraced the Williams philosophy fully. In 1969, he raised his batting average to .278, lifted his on-base percentage to a career-best .414, and hit 30 home runs. For the first time in his career, Epstein received some support in the American League MVP race.

At 26 years of age, Epstein seemed on the verge of stardom, especially with Williams in his corner. Then came a setback. Rather shockingly, his batting average, home runs, and walks numbers all decreased in 1970. In particular, he struggled against left-handed pitching. At times, he sparred with Williams. The tension with the manager seemed to affect Epstein; he finished the season with an OPS of .815, which was certainly respectable but not indicative of a superstar.

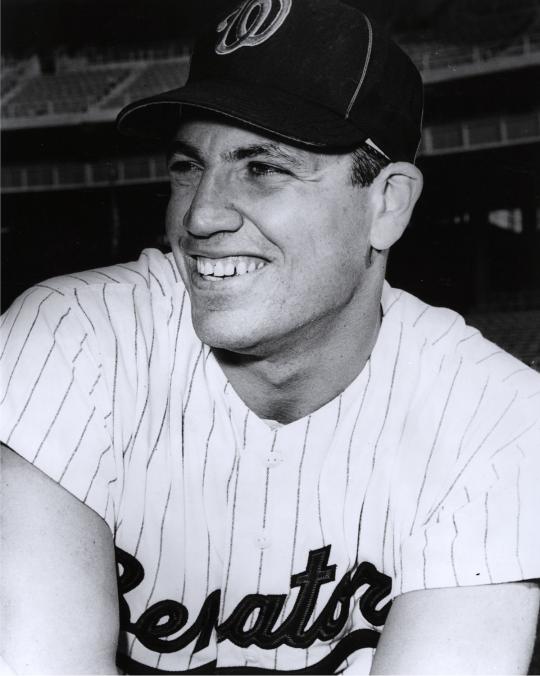

Hoping to bounce back in 1971, Epstein instead found himself in a slump. He started the season so poorly that the Senators decided to move on. In early May, they pulled off a major trade with the A’s, sending Epstein and lefty reliever Darold Knowles to Oakland for first baseman Don Mincher, backup catcher Frank Fernandez and reliever Paul Lindblad.

A’s owner Charlie Finley felt that he pulled off a coup, acquiring a 28-year-old slugger in Epstein for a 33-year-old in Mincher. Epstein was no less thrilled. Not only was he leaving a second-division team like the Senators, but he was joining a contending team that allowed him to be closer to the rest of his family, which resided in California.

The trade did bring one potential detriment: The very real possibility of being platooned. In the past, Epstein had battled with Ted Williams over this same issue. Williams didn’t believe that Epstein could hit lefties well enough to play every day.

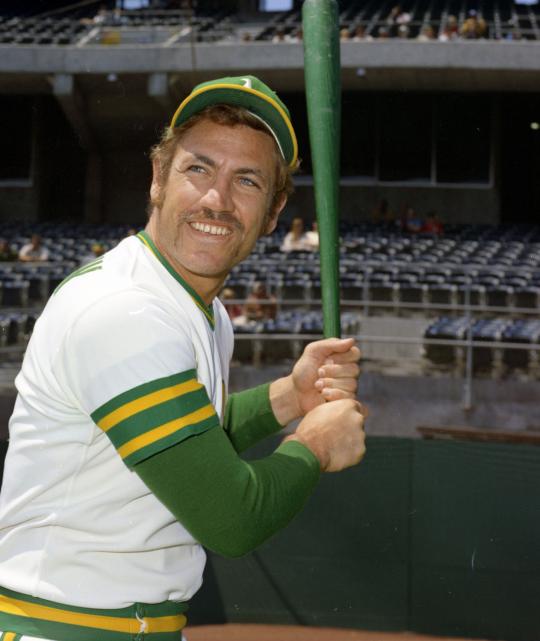

This time, Epstein had to share time with a right-handed hitter, veteran Tommy Davis. But Epstein did not complain about the situation and hit well, clubbing 10 home runs in his first six weeks with Oakland. Tailing off in September, Epstein hit 18 home runs and posted an OPS of .805 with the A’s.

Unfortunately, Epstein’s struggles in September convinced his manager, future Hall of Famer Dick Williams, to bench him for a good portion of the ALCS. Epstein played sparingly during the three-game sweep at the hands of Baltimore.

Epstein presented a strange defense of his late-season performance. “You can’t expect superstar statistics from someone not making superstar money,” Epstein said in an interview with the Sporting News. “I’m just an average ballplayer trying to do his job. Why do people expect me to hit 40 or even 30 home runs a year? I’ll hit 20.”

Epstein’s late slump and subsequent postseason benching had him depressed to the point that he considered quitting the game entirely. Ultimately, Epstein reconsidered. Believing that his late-season travails had been caused by fatigue, Epstein decided that he needed to lose weight.

Epstein dropped 30 pounds over the winter, bringing him to 205 pounds, the lightest weight of his career. The weight loss paid dividends during the first half of the season. In early June, Epstein embarked on a home run tear, cementing his favor with the manager.

The situation changed somewhat on June 17, when Epstein hit a weak pop fly and did not run hard to first base. With no tolerance for a lack of hustle, Dick Williams pulled him from the game.

The 1972 season also brought difficulty from a source outside of baseball. When news came down on Sept. 5 that terrorists had murdered 11 Israeli athletes and coaches during the Olympic Games in Munich, Epstein and teammates Ken Holtzman and Reggie Jackson offered a poignant response, donning black armbands in tribute to those who had been murdered.

In terms of on-field performance, Epstein played well for most of the season. He hit 26 home runs, greatly cut down on his strikeouts, raised his walks, and compiled an OPS of .866. Epstein’s power hitting helped the A’s win their second consecutive division title, before they moved on to beat the Detroit Tigers in the ALCS.

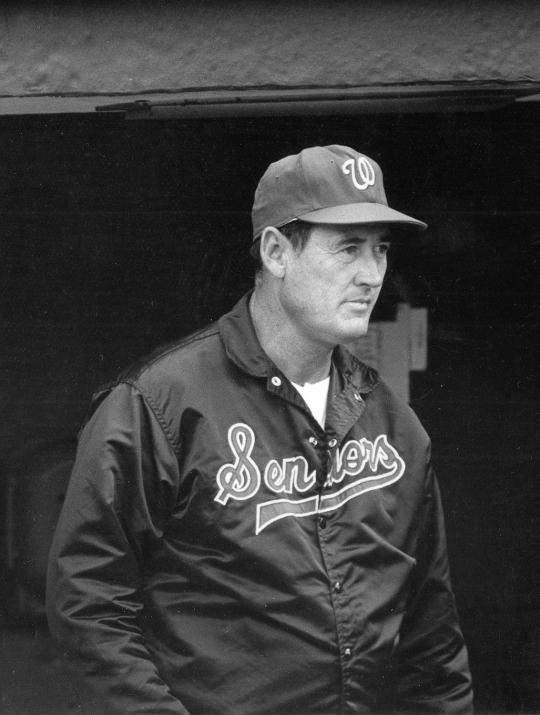

The Baltimore Orioles were so impressed with Mike Epstein's hitting in Single-A that they had him bypass Double-A ball in 1966. They promoted him all the way to Triple-A, where he played for the Rochester Red Wings of the International League. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

It was on to the World Series, where controversy once again enveloped Epstein. Managing the late innings of Game 2 and hoping to maintain a two-run lead, Dick Williams replaced the weak-fielding Epstein with Mike Hegan. A brilliant fielder, Hegan made a remarkable backhand stop on a hard-hit grounder by Cesar Geronimo, helping to preserve the victory. After the game, Epstein stewed about being taken out while ignoring the importance of Hegan’s phenomenal play. On the team flight, Epstein approached Williams and warned him about ever taking him out of a game under similar circumstances in the future. The two men exchanged heated words.

The A’s would go on to win the World Series, but Epstein’s exchange with Williams cemented his fate with the organization. On Nov. 30, the A’s made a strange trade, sending Epstein to the Texas Rangers for a little known middle reliever, Horacio Pina. The trade was puzzling, but Finley explained that he had been forced to trade Epstein to make room for Gene Tenace, whose injured shoulder limited his ability to catch, forcing the A’s to play him at first base. With the DH rule coming in to play, however, Epstein would have made perfect sense for that role.

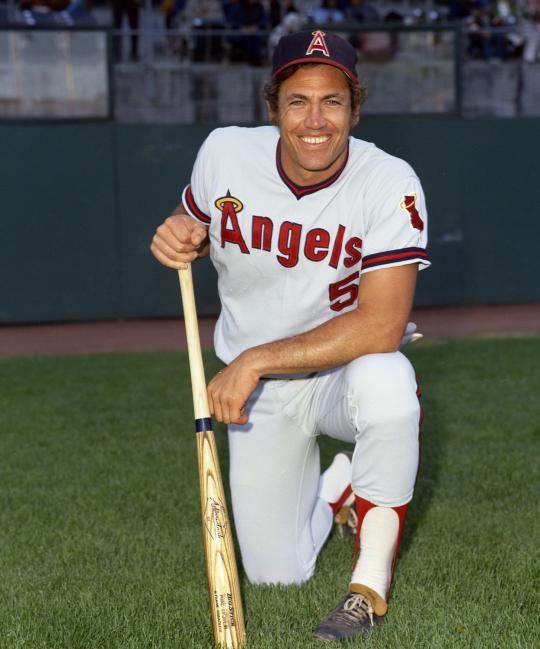

No matter the reasoning for the trade, Epstein was now a Ranger – but not for long. He lasted 27 games in Texas, hit very poorly, and found himself heading back to California, this time in a trade with the Angels. The Rangers sent Epstein, catcher Rick Stelmaszek and right-hander Rich Hand to California for Jim Spencer and right-hander Lloyd Allen. The Angels made Epstein their starting first baseman, hoping desperately that he would provide some much-needed left-hand power. It didn’t happen, as he batted only .215 with eight home runs in 91 games. He also clashed with manager Bobby Winkles, only adding to his difficulties in Southern California.

Epstein remained the Angels’ first baseman through the spring of 1974, but his hitting never responded. On May 4, with his average sitting at .161, the Angels released the left-handed slugger. Even though Epstein was only 31 years old and just two years removed from a fine season with a world championship team, no one else offered him a contract. Finley expressed some interest, but then had second thoughts. Epstein had no real choice but to retire.

It’s always been something of a mystery why Epstein couldn’t find a job playing first base or serving as a DH with another team, given that he was still relatively young. At the time, Epstein claimed that he was burned out, but were other factors involved? Did his bat speed slow to an unmanageable level at an unusually young age? Or was he ignored by all 24 teams because of his temperamental reactions to his managers, including Ted and Dick Williams? The answers to those questions remain elusive.

After playing, Epstein would eventually find his niche. He took a turn as a minor league manager with the Milwaukee Brewers’ organization, but his hitting philosophies did not mesh with the Charley Lau approach that was popular with a number of teams at the time. So Epstein left Organized Ball and became an independent hitting instructor. Founding his own hitting school, he has developed a system known as “rotational” hitting, with much of it based on the teachings that came from Ted Williams. (By then, he and Williams had become friends, maintaining that relationship until the latter’s death in 2002.) With his high level of intelligence and ability to speak well and clearly, Epstein has found his niche as an instructor.

Back in 2004, Epstein came to Cooperstown to participate in the first-ever Jewish Baseball Weekend at the Hall of Fame. A number of former big leaguers attended, including Ron Blomberg, Ken Holtzman, Elliott Maddox and Richie Scheinblum. Epstein spent part of the weekend putting on a hitting clinic at the nearby Clark Sports Center, where he was also made available to the media. I wanted to interview him, but was a little bit leery because of his reputation for being moody and temperamental. That scouting report turned out to be completely false. Epstein was not only approachable, but very enthusiastic about being in Cooperstown. He also loved to talk about hitting. At the end of our interview, he made a point of telling me that he liked my questions and my interviewing style. That’s the kind of reaction that writers don’t often hear from their interview subjects.

Epstein made a great impression that day. His visit remains a highlight of my time in Cooperstown. It’s just another reason why I enjoy Mike Epstein’s poetic 1973 Topps card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame