- Home

- Our Stories

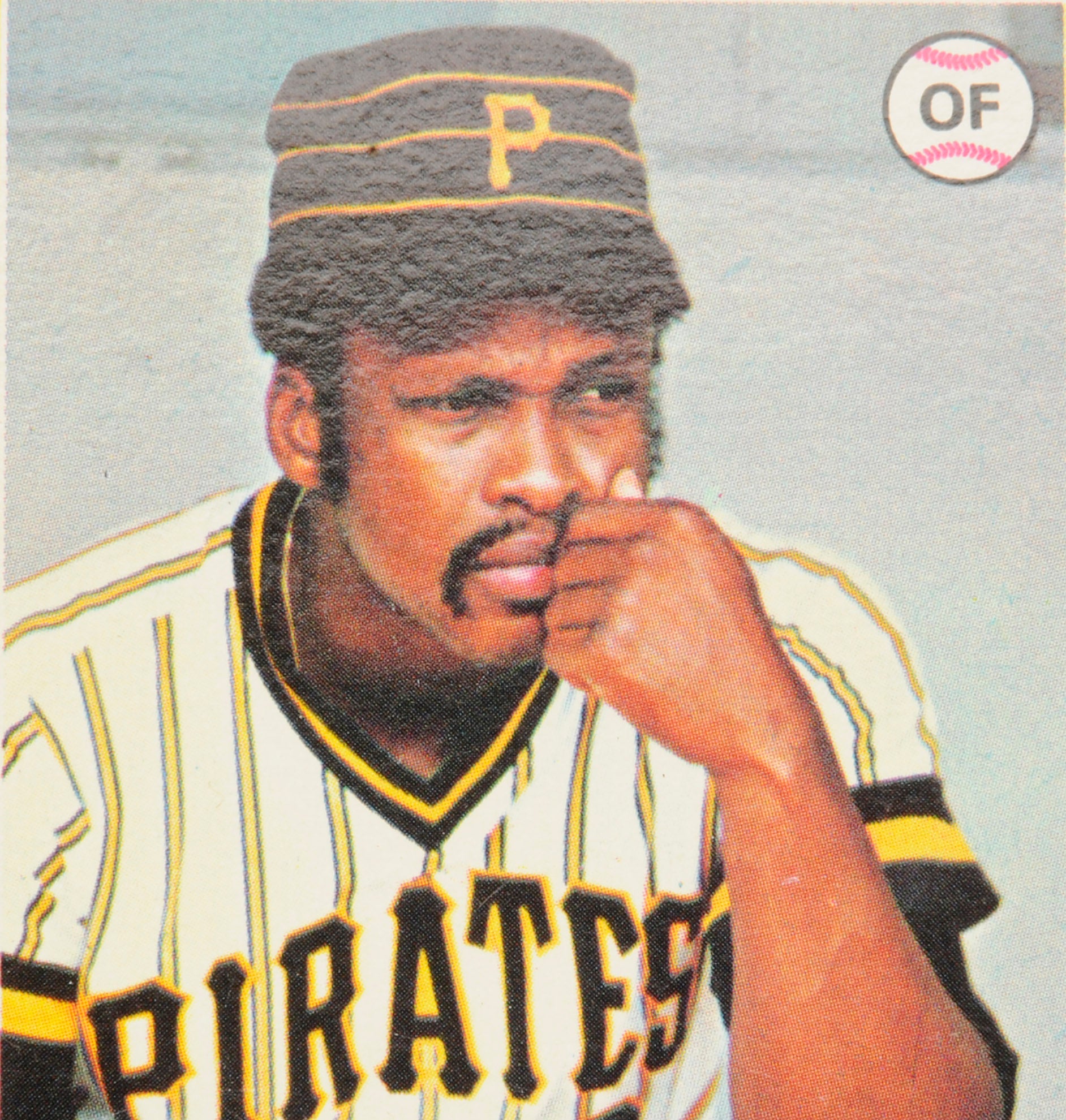

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Ruppert Jones

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Ruppert Jones

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

One of my favorite shows from the 1970s was M*A*S*H. One of the early episodes, a 1974 gem titled “Springtime,” dealt with Radar O’Reilly’s interest in a nurse who liked poetry and all things literary. So Radar decided to brush up on some poetry himself, finding a book by 19th century English poet Rupert Brooke. In recalling the work of the poet, Radar referred to him as “Ruptured” Brooke. This was classic Radar, as played so wonderfully by Gary Burghoff.

So when Ruppert Jones – the only Ruppert to ever play in the major leagues – came onto the scene a few years later, it was only natural that a few of us young collector/fans joked about the new outfielder, whom we referred to as Ruptured Jones. We chuckled over that, as if we were some sort of comic geniuses, but soon came to realize that Jones could play.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

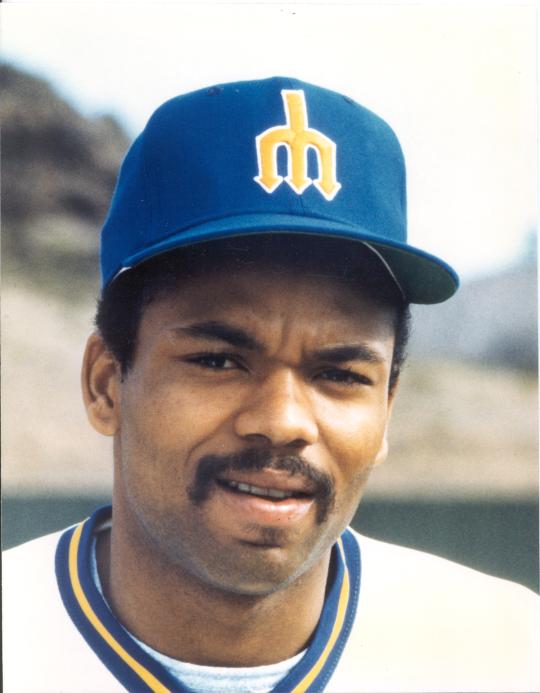

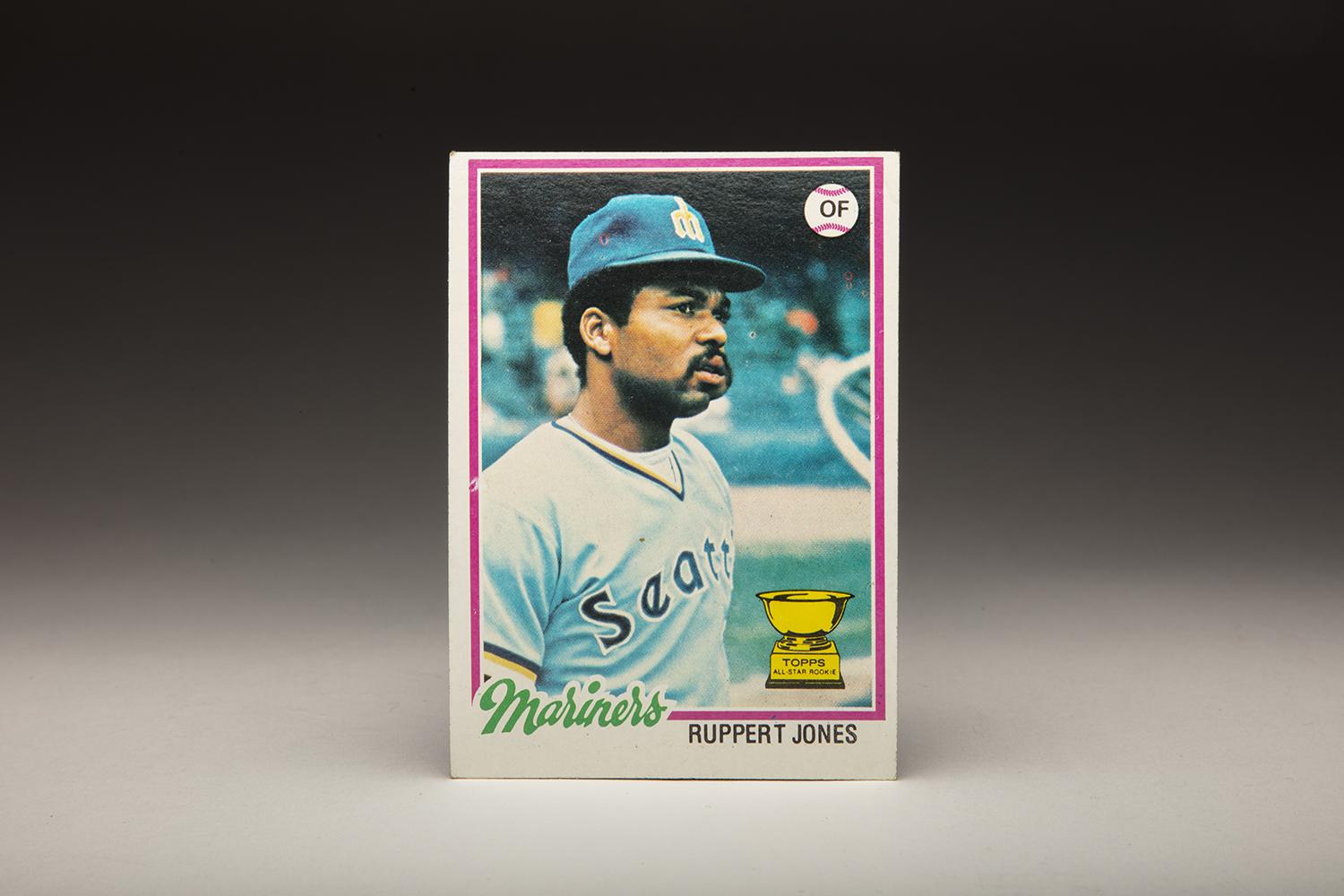

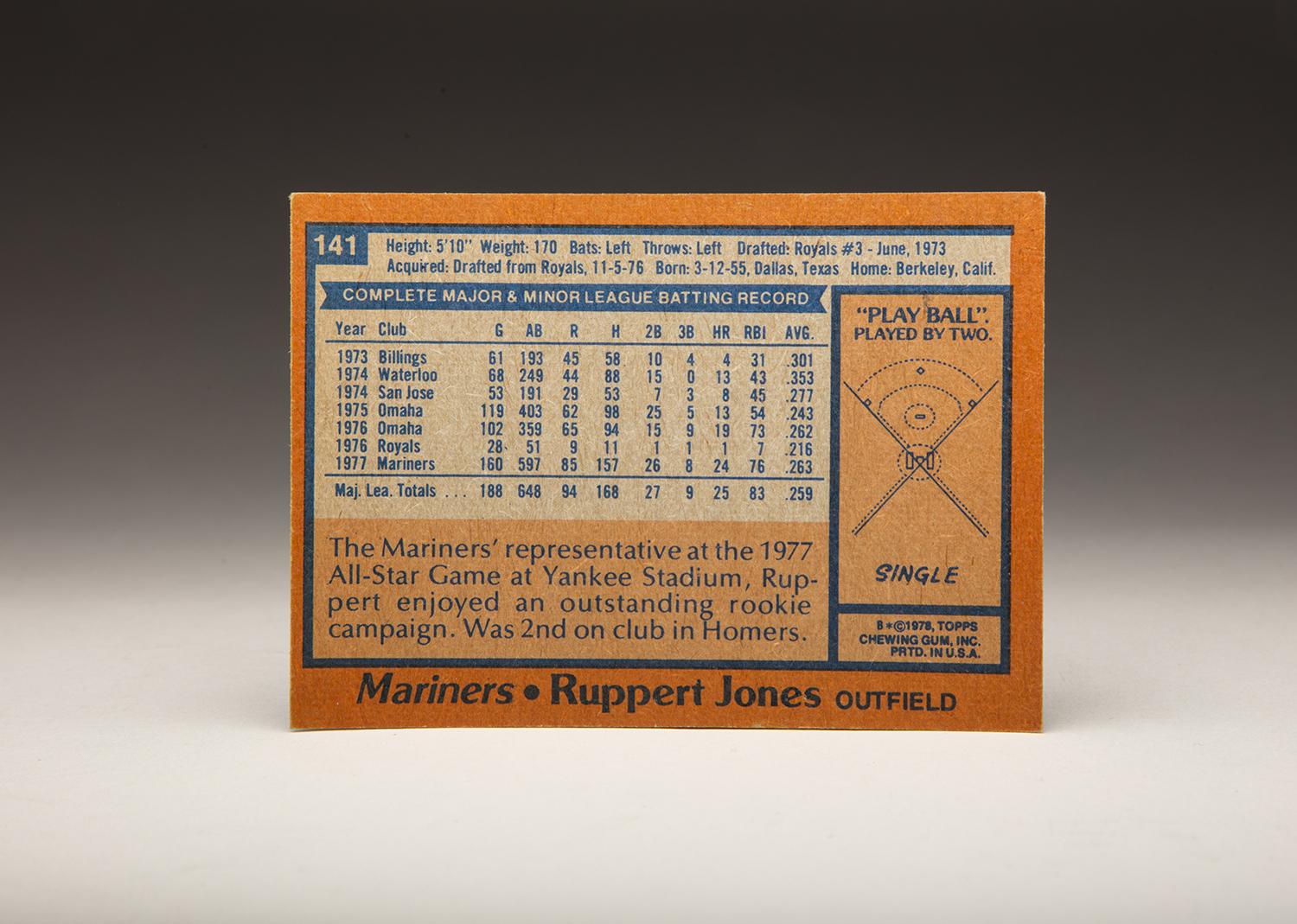

Jones received his first exclusive baseball card in 1978. (In 1977, he shared a “Rookie Card” with three other prospects, including Jack Clark and Lee Mazzilli.) I’ve come to appreciate the card for a variety of reasons. First, the ’78 set is arguably the best offering from Topps during the late 1970s. The simple design, consisting of a thin colored line near the border and the team name in colorful script, works well, allowing the photograph to breath. Second, the Jones shows off the road uniform colors used by the Seattle Mariners in their first season. We also see Jones wearing the Mariners’ vintage cap, highlighted by that memorable trident. I loved both the trident and the bluish-green tint of the uniforms and never understood why the Mariners abandoned the logo and the look in the late 1980s.

The Jones card is also notable for the inclusion of Topps’ iconic “All Star Rookie” cup. Each season, Topps selected an all-rookie team; every selection received the cup designation on his card, always featured in bright yellow for some reason. I can’t imagine that the real cup was actually yellow, but Topps went with that color on the animated cup, perhaps because it stood out so intensely against the rest of the card. I mean, how could you not notice that incredibly bright yellow cup?

Jones deserved his all-rookie ranking, even though he did not receive a single vote in the Rookie of the Year balloting. But before delving further into his rookie season, let’s go back to his days as an amateur ballplayer. Even in his youth, Jones found himself playing with major league talent. His teammates at Berkeley High School included Claudell Washington and Glenn Burke, both of whom would make the major leagues. Jones drew some interest from major leagues teams, along with several colleges that offered football scholarships, but he chose baseball, his stronger sport. In 1973, the Kansas City Royals made him their third-round selection in the annual June draft.

A left-handed hitter with power and speed, Jones moved up quickly within the Royals’ system. He hit at almost every minor league level, earning a promotion to Kansas City by 1976. As much talent as Jones possessed, he also found himself blocked by Amos Otis in center field and Al Cowens in right field. The Royals had another top prospect close to ready in Willie Wilson, who was primed to take over in left. So that position was blocked, too. With such a glut of talent in their outfield and throughout their 40-man roster, the Royals found themselves unable to protect all of their top prospects from the upcoming expansion draft. Ultimately, they protected Wilson and young shortstop U.L. Washington, but left Jones available for the taking.

As one of two new expansion teams, the Seattle Mariners had the first pick in the draft. They jumped at the chance to take Jones, a supreme five-tool talent who looked like a star in the making. The Mariners penciled in Jones as their starting center fielder. In Seattle’s inaugural season of 1977, Jones played 160 games, clubbed 24 home runs, and drew 55 walks. He earned selection to the American League All-Star team, the only Mariners player chosen that summer.

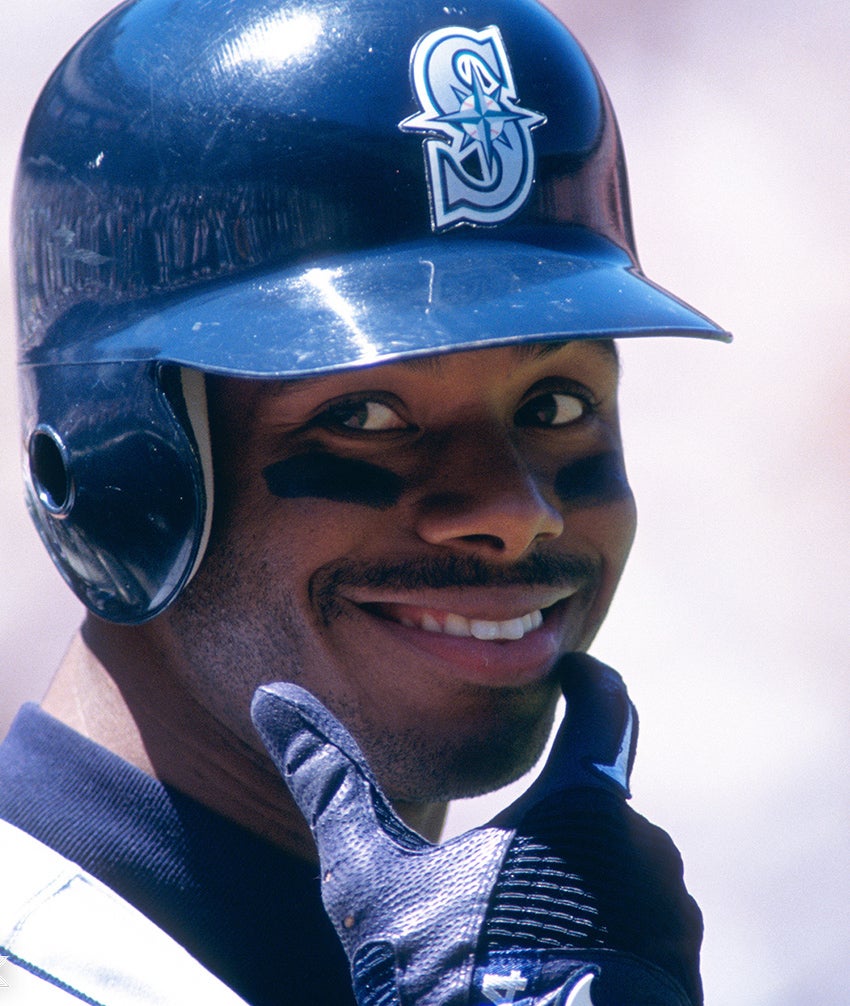

Jones became popular in Seattle, where the fans created a section in the center field bleachers known as “Rupe’s Troops.” Jones developed a cult following; as each of his at-bats was announced over the Kingdome PA system, the fans chanted “ROOP” over and over again. For a short time, he was as popular as Ken Griffey, Jr. would become more than a decade later.

As well as Jones played in his first full season, he received no consideration in the Rookie of the Year vote in 1977. The reason? It was simply a strong year for rookies. Hall of Famer Eddie Murray won the award, while outfielder Mitchell Page, who had a terrific season for the Oakland A’s, finished second. Bump Wills of the Texas Rangers, who posted an OPS of .771 as a second baseman, placed third. And then there was Detroit right-hander Dave Rozema, who won 15 games for a subpar Tigers team. With such a strong class of rookies, there was simply no room for Jones on the ballot for many voters.

Based on his first season and his combination of power and speed, the Mariners envisioned Jones as the cornerstone to their franchise. At 22 years old, he was still very young, with enough room for future growth. The Mariners believed that he would blossom into stardom, but his second season in Seattle brought only disappointment. After undergoing offseason knee surgery, Jones’ batting average fell off to .235.

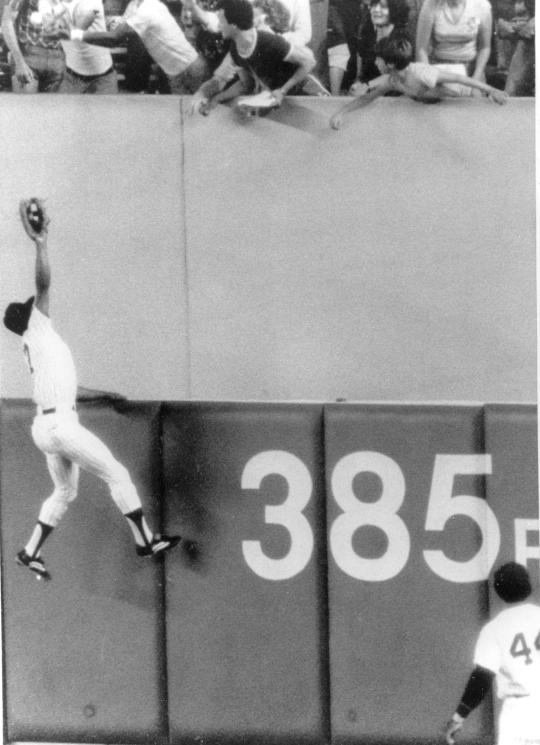

Jones suffered another setback, too. In June, he was rushed to the hospital, where he had to undergo an emergency appendectomy. Losing 15 pounds after the surgery, Jones’ power suffered. By the end of the 1978 season, he hit only six home runs. It was only on defense that Jones continued to excel, making a variety of circus catches. Yet, it was no longer obvious that he was the Mariners’ best player. Some who followed the Mariners pointed to Leon Roberts, a slugger who put up far better offensive numbers in 1978.

It didn’t take long for Jones to bounce back. In 1979, he hit 21 home runs, drew 85 walks, and lifted his OPS to nearly .800. He also played an excellent center field, adding a string of spectacular catches to his growing highlight reel.

Based on two fine seasons out of three, Jones should have remained in Seattle for years to come. But as a team, the Mariners were struggling, having finished in sixth place in 1979. They needed help across the board. When it came to trade talk, other teams invariably asked about Jones. When the New York Yankees approached Seattle about Jones, the Mariners listened. The Yankees offered power-hitting catching prospect, Jerry Narron, along with their top pitching prospect, Jim Beattie. They also included minor league right-hander Rick Anderson and veteran outfielder Juan Beniquez, who could replace Jones in center field. Mariners general manager Lou Gorman contemplated the offer before ultimately saying yes to the six-player blockbuster.

It didn’t take long for Jones to bounce back. In 1979, he hit 21 home runs, drew 85 walks, and lifted his OPS to nearly .800. He also played an excellent center field, adding a string of spectacular catches to his growing highlight reel.

Based on two fine seasons out of three, Jones should have remained in Seattle for years to come. But as a team, the Mariners were struggling, having finished in sixth place in 1979. They needed help across the board. When it came to trade talk, other teams invariably asked about Jones. When the New York Yankees approached Seattle about Jones, the Mariners listened. The Yankees offered power-hitting catching prospect, Jerry Narron, along with their top pitching prospect, Jim Beattie. They also included minor league right-hander Rick Anderson and veteran outfielder Juan Beniquez, who could replace Jones in center field. Mariners general manager Lou Gorman contemplated the offer before ultimately saying yes to the six-player blockbuster.

While some athletes might have expressed trepidation over playing in New York, Jones embraced the pending change. “I have a lot of confidence in my ability, I think I had a pretty good year [for Seattle], but nobody noticed,” Jones told the Sporting News. “Next year, playing in New York, they’ll notice.”

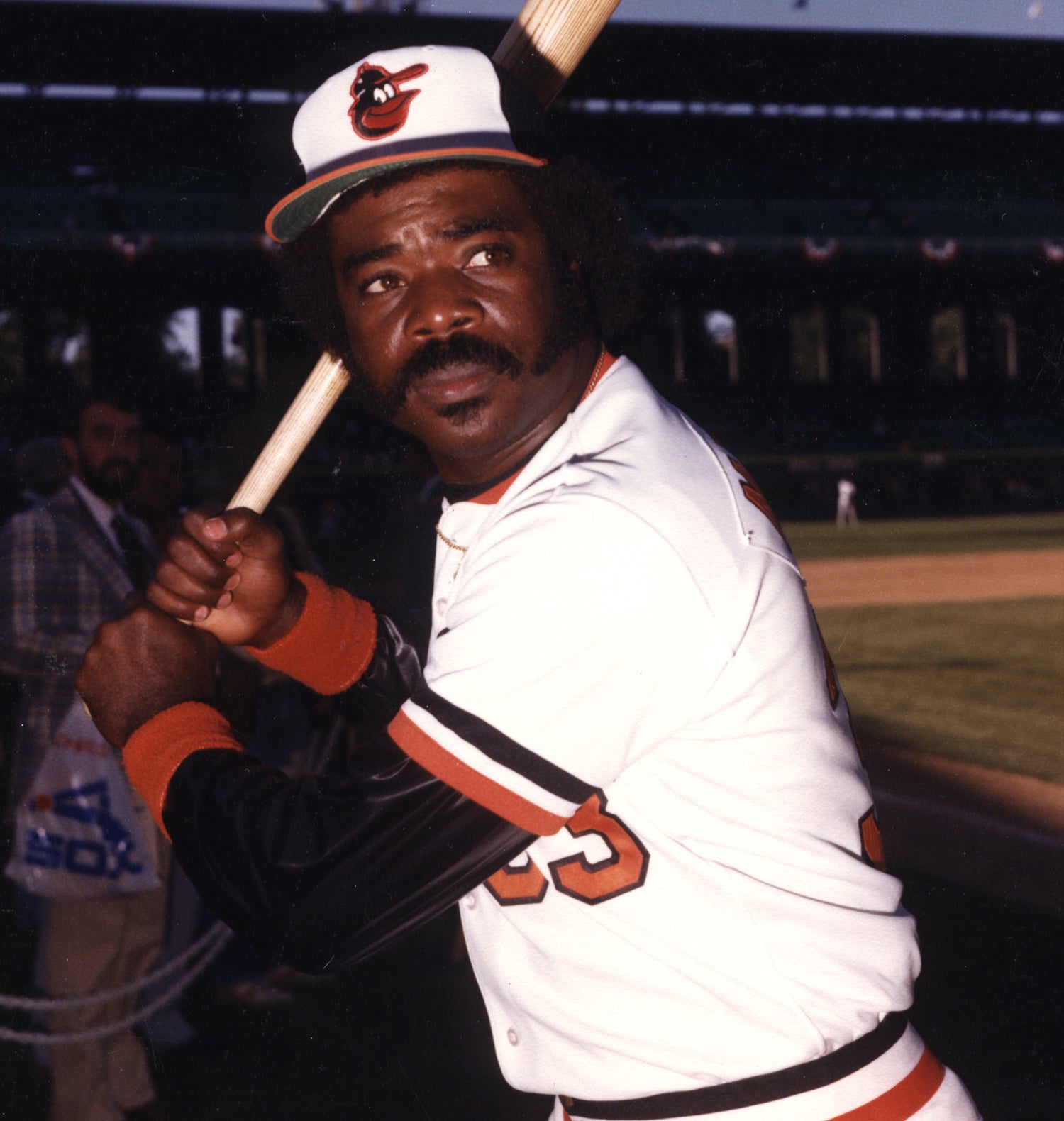

The trade certainly created excitement in New York, where the Yankees had struggled through a disappointing season. The New York media, known for being critical, gave its full approval to the trade, calling a Jones a future superstar. The aging Yankees needed a new center fielder, and Jones appeared to be the ideal successor to Mickey Rivers, who had been traded near the end of the 1979 season. With his ability to run down fly balls in Yankee Stadium’s “Death Valley,” along with a powerful left-handed swing, Jones looked like a perfect fit for the Bombers.

Jones’ debut with the Yankees did not go well. He slumped in April and May, his batting average falling into the .220s. He then came down with severe abdominal pain, which turned out to be an intestinal obstruction. The problem was related to his earlier appendectomy. As a result, Jones missed six weeks of action.

Jones returned to the Yankees in July, but his hitting failed to pick up. He had developed a hitch in his swing, noticed by opposing scouts and pitchers, which made him vulnerable to high fastballs. The Yankees tried to cut down the hitch, but Jones continued to struggle. And then in late August, another physical setback occurred. Playing center field at the Oakland Coliseum, Jones attempted to make a catch in deep center and ran into the outfield fence. The collision knocked Jones out for three to four minutes; it resulted in a concussion and a separated shoulder, the latter injury sidelining Jones for the balance of the season.

After hitting the wall, Jones recalled nothing about the night. “People tell me what happened,” Jones said later, “but there’s a whole night of my life I don’t remember. Initially, I was just grateful I was still alive. When I woke up [the next day] feeling somewhat fine and alive, I was relieved.”

No one knew it at the time, but Jones would never play another regular season game for the Yankees. He went to Spring Training with New York in 1981, but rumors persisted about the Yankees’ pursuit of another outfielder. In late March, the Yankees announced a pair of blockbuster deals. One involved the acquisition of power-hitting first baseman Jason Thompson from the California Angels. The other involved a veteran center fielder with the San Diego Padres.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn stepped into the Thompson trade, negating the deal because the Yankees had exceeded the amount of cash that could be included in any one trade. But the other deal stood. It sent Jones and three prospects – outfielder Joe Lefebvre and left-handers Tim Lollar and Chris Welsh – to San Diego for center fielder Jerry Mumphrey and right-hander John Pacella. Just like that, Jones’ career in pinstripes was over.

Jones worked hard to improve his conditioning and cut down on the hitch in his swing, but found the results no better in 1981. He batted only .249, with a mere four home runs, during the strike-shortened season. But by 1982, he had rediscovered his game. Jones batted .283 (a career high at that point), drew 62 walks, and hit 12 home runs. Based on a strong first half to the season, in which he sustained a batting average of better than .300, Jones made the All-Star team for a second time.

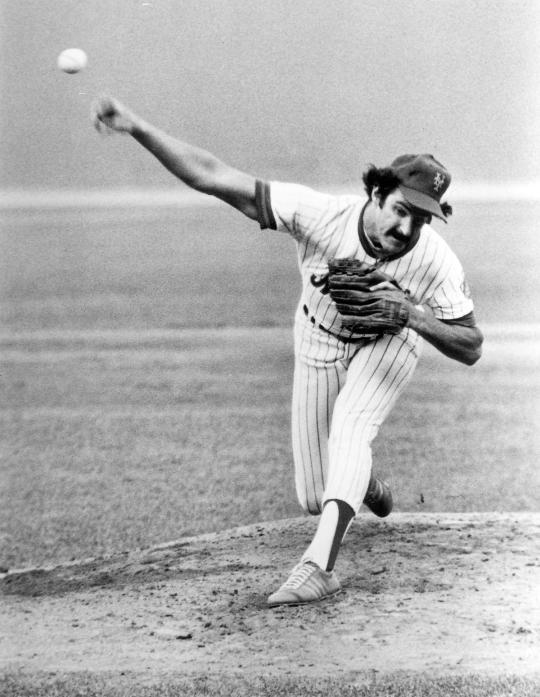

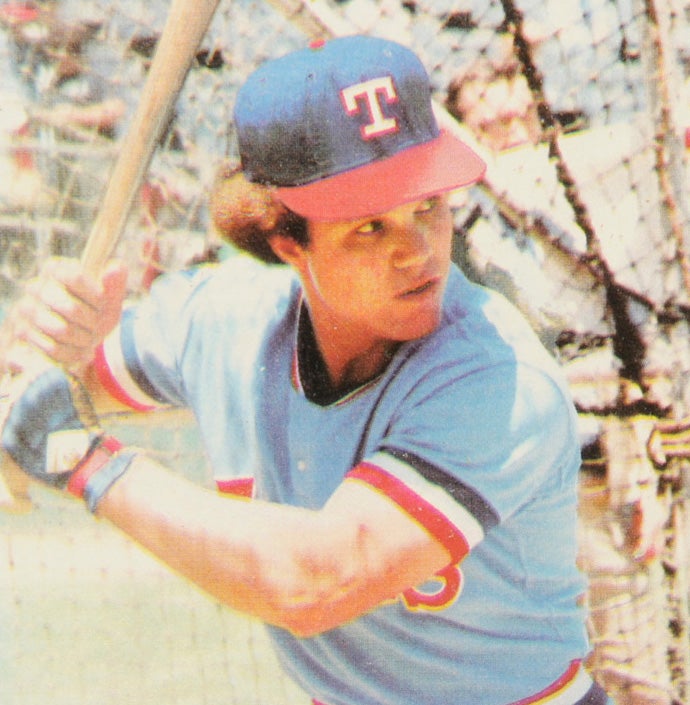

For the New York Yankees, Ruppert Jones appeared to be the ideal successor to Mickey Rivers (pictured above), who had been traded to the Rangers midway through the 1979 season. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

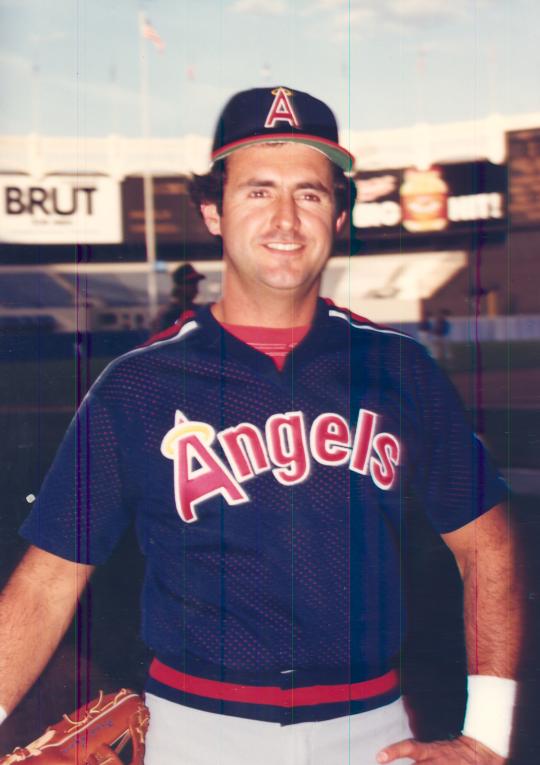

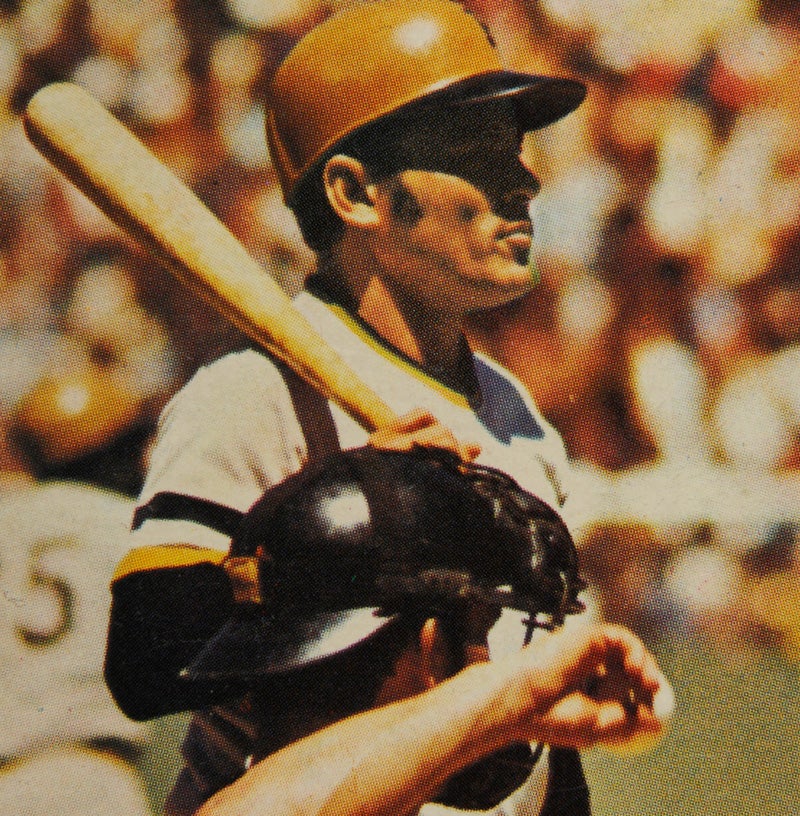

On March 31, 1981, Ruppert Jones was traded by the New York Yankees with Joe Lefebvre, Tim Lollar and Chris Welsh to the San Diego Padres for Jerry Mumphrey and John Pacella (pictured above). (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In 1983, Jones’ performance dipped again. His average fell to .233 and he walked only 33 times, not exactly ideal numbers for a player headed to free agency. Frustrated by his inconsistency, the Padres decided to pass on bringing him back for 1984. Other teams showed little interest in signing him. The Pittsburgh Pirates did offer him a Spring Training invite, but with no guarantee that he would make the team.

Jones took the Pirates’ offer, but did not play well enough that spring to earn a spot on the Opening Day roster. The Pirates released him, leaving his future in doubt, but then Detroit Tigers general manager Bill Lajoie came calling. Lajoie offered Jones a deal, but told him he would have to start the season at Triple-A before receiving a call-up.

In June, the Tigers promoted Jones to Detroit. Jones’ timing could not have been better. The Tigers were on the cusp of greatness. They found a role for Jones as a fill-in left fielder and center fielder, and occasional DH. Becoming part of a deep and powerful bench, Jones played a small but contributing role for the Tigers, who proceeded to run away with the American League East on their way to a world championship. Jones did not play much in either the Championship Series or the World Series, but still earned his first and only world championship ring.

For the Tigers, Jones average one home run per 18 at-bats, a terrific ratio for a part-time player, but he departed as a free agent at season’s end. The California Angels, who had just lost Fred Lynn to free agency, showed interest and signed Jones to a contract. For the next three seasons, Jones filled a role as a part-time center fielder, right-fielder, and DH. He hit well in his first two seasons in California, and then went through a downturn in 1987, leading to his release.

Still only 32, Jones did not give up. The Milwaukee Brewers offered him an invite to Spring Training. He hit well in exhibition games, but a shoulder injury prevented him from playing the outfield. The Brewers felt that Jones needed to be able to play a position to make the team, so they released him in spring training. Jones hooked on with the Texas Rangers’ Triple-A team before taking his skills to Japan. After a so-so half season with Hanshin of the Japanese Leagues, he returned to the states, put in some more time at Triple-A Oklahoma City, and then called it a career.

Ever since his playing days, Jones has remained out of baseball. He has found success working in the insurance business, specifically selling employee benefits to government contractors. He retains no long-term friends from his baseball days, but lives happily with his family in the suburbs of San Diego.

While Jones never lived up to the expectations that were thrust upon him in Seattle and New York, he can take pride in a 12-year career that produced 147 home runs and 143 stolen bases. He is still remembered in Seattle, even in a town where the younger Griffey and Edgar Martinez have surpassed him in popularity. He also has that world championship ring from 1984, when the Tigers ruled the world.

With apologies to the great Radar O’Reilly, there’s nothing “ruptured” about that kind of a career in baseball.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame