- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bob Montgomery

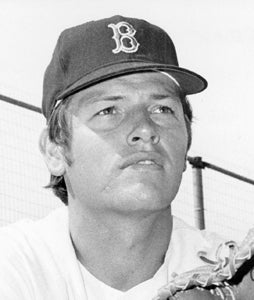

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bob Montgomery

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

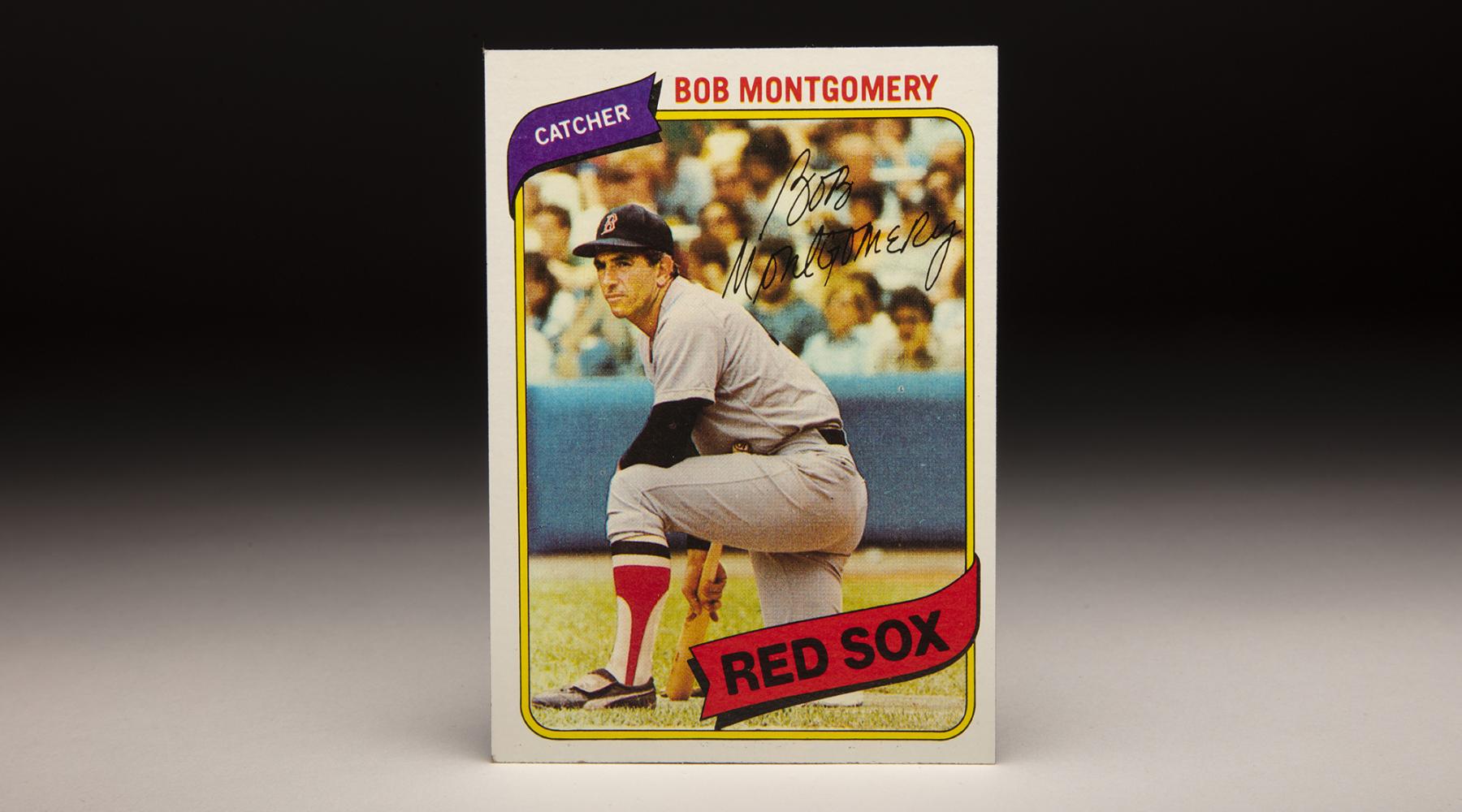

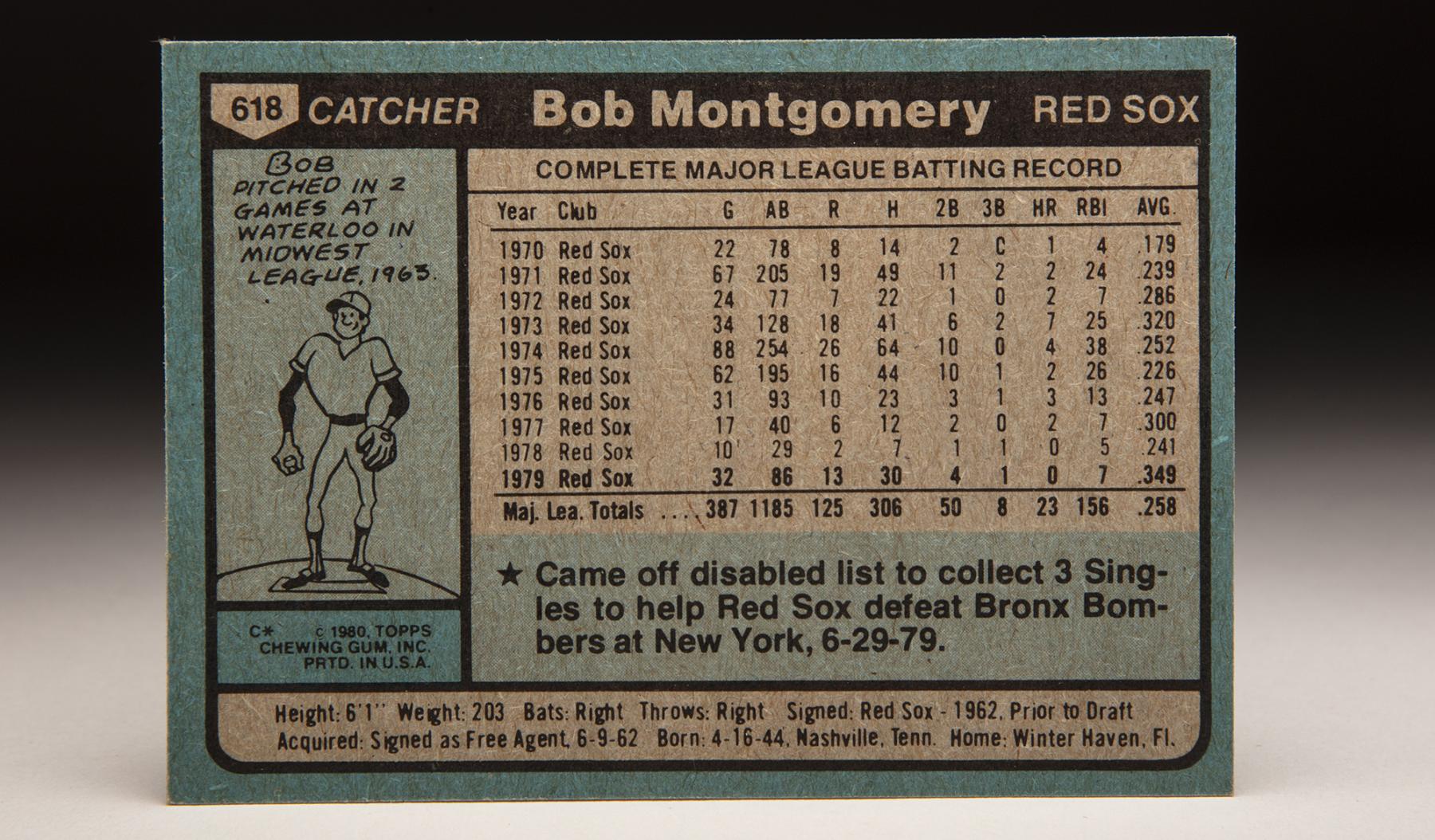

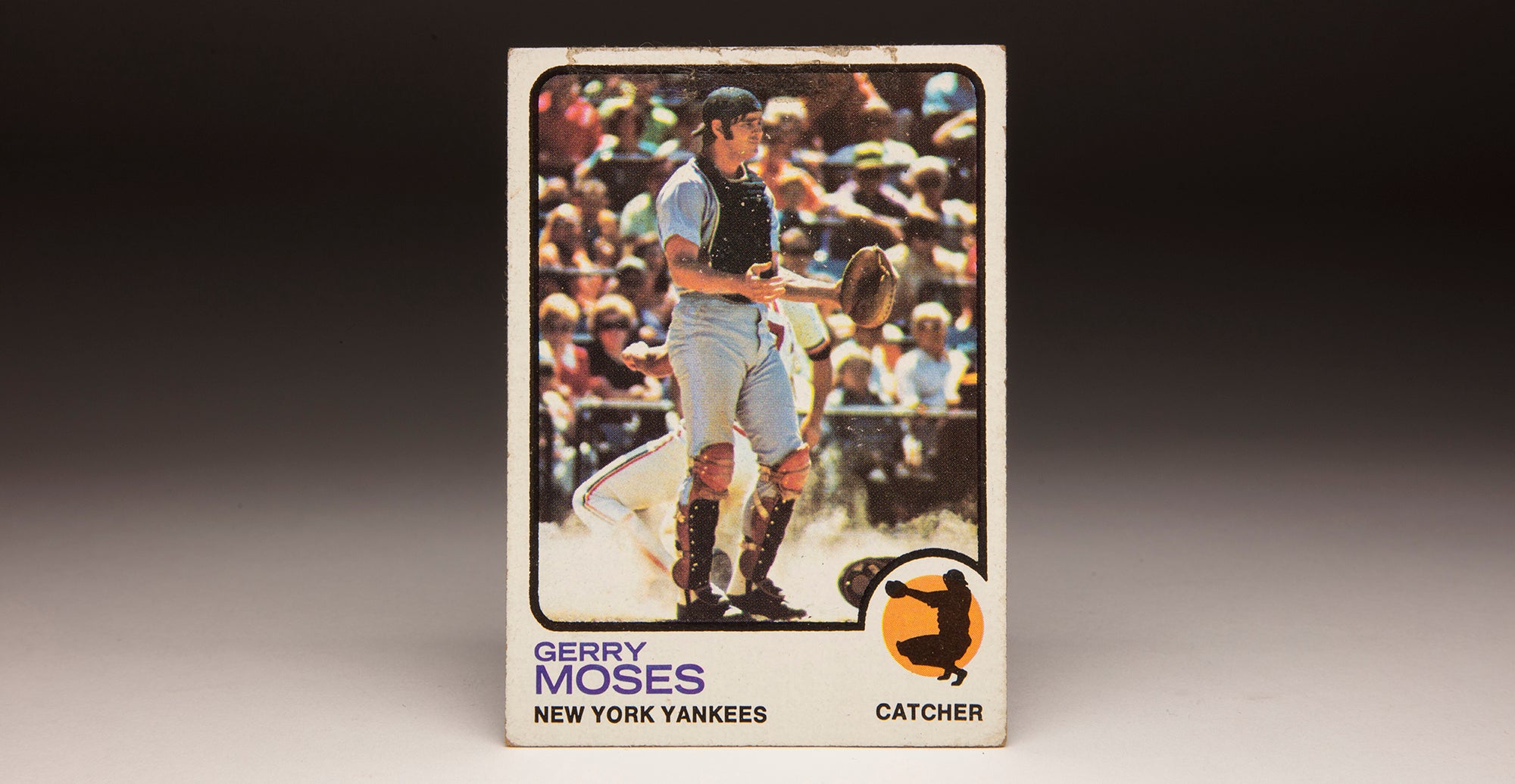

Something seems amiss on Bob Montgomery’s 1980 Topps card. He is kneeling in the on-deck circle, bat in hand, ready to take his place in the batter’s box. But a closer look shows us that Montgomery is wearing a soft cap, and not a protective helmet. In fact, there is no helmet to be found anywhere in the on-deck circle.

What is going on here? Where is Montgomery’s helmet?

The short answer is this: Bob Montgomery did not have a helmet. The last of a vanishing breed, Montgomery was literally the last man to take an at-bat in a major league game without wearing a helmet. His final appearance came in 1979, one year before this card came out. Let’s put that in perspective. For the last 40 years, or the equivalent of two generations, we have seen every big league batter take his place in the batter’s box while wearing a protective helmet, either the old-fashioned kind without a flap, or a flapped helmet, as is the standard today. Some players have even worn helmets with flaps on both ears.

Montgomery’s final game in 1979 came eight years after Major League Baseball decided to install a significant rule change and make helmets mandatory for all hitters. But that 1971 rule included a grandfather clause, which allowed established players to continue wearing caps to the plate if they so desired. That clause came with one caveat: Any player using a cap would have to wear a protective plastic liner inside of the cap to give him at least some protection against potential beanballs.

Given the dangers of facing a 95-mile-per-hour fastball, it might have seemed logical that every player would have started donning helmets in 1971, but that was clearly not the case. According to the best available research, at least three players invoked the 1971 grandfather clause. In addition to Montgomery, they included Norm Cash, the longtime first baseman for the Detroit Tigers. He would continue to play without a helmet until his final game in 1974.

And then there was veteran infielder Tony Taylor, who at the time was Cash’s teammate in Detroit. When Taylor retired at the end of the 1976 season, that left Montgomery as the last man standing, the final player to take an at-bat without a hard hat on his head.

For teammates who knew about one of Montgomery’s off-the-field hobbies, his decision to bat without a helmet probably created little surprise. After all, Montgomery was well known for having acquired his pilot’s license, allowing him to travel by air while attending Red Sox Spring Training in Winter Haven. Given Montgomery’s bravery in flying a rented plane, it’s likely that batting without a helmet seemed relatively tame.

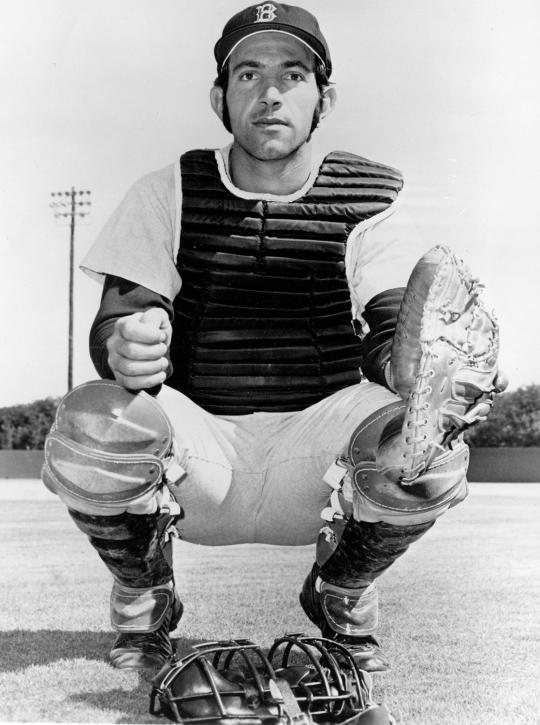

Although Montgomery never became a household name nationally, Red Sox fans of a certain age will remember him. He served as a longtime backup catcher to a fellow named Carlton Fisk. At one time, back in the 1960s, some scouts considered Montgomery a top-notch prospect and the team’s catcher of the future – at least until the arrival of Fisk.

Montgomery debuted in the professional ranks in 1962, when the Red Sox signed him as an amateur free agent. They assigned him to Olean of the NY-Penn League, which at the time was listed as Class D ball. Playing third base and the outfield, Montgomery did well, hitting a respectable .273 with an OPS of just over .800.

The following summer, the Red Sox moved Monty up to Class A Waterloo, where his manager, Len Okrie, suggested that he switch positions. Okrie felt that Montgomery lacked the power that most teams wanted from a third baseman or corner outfielder. The manager suggested that he try catching; Montgomery agreed to the switch.

Ironically, Montgomery started to show some ability as a power hitter that season. He hit 16 home runs in 119 games and slugged a decent .444. He spent most of his time at third base, but also caught a few games.

In 1964, Montgomery made the full-time transition to catcher. Continuing to hit with power while doing solid work behind the plate, Montgomery spent most of the season at Waterloo and made the Midwest League All-Star team before being rewarded with a late-season promotion. Bypassing Double-A completely, Montgomery reported to Triple-A Seattle, finishing out the season by appearing in seven games.

Strangely, the Red Sox sent Montgomery back to Class A in 1965. Montgomery’s hitting regressed, as he hit only two home runs and batted .239. In 1966, he received a bump to Double-A Pittsfield and hit .292, albeit with scant power. Late in the summer, the Red Sox assigned him to their Triple-A affiliate at Toronto, where he batted .324.

The more that he caught, the more that Montgomery drew favorable reviews from scouts for his overall defensive prowess and his strong throwing arm. He also showed increased power at the plate. The consensus of most scouts projected Montgomery on the fast track to Boston.

But that track would turn into a bumpy road. For the next three seasons, Montgomery remained stuck in Triple-A, his career stalled by injuries and a lack of consistent hitting. Finally, in 1970, he broke through, batting .324 with 14 home runs and an OPS of .859. It was the kind of performance that Montgomery, now 26, needed to earn a promotion to Boston. In September, with the rosters expanding, the Red Sox called up their nine-year minor league veteran.

Along that long minor league path, Montgomery had refused to give up the chase.

“I never became discouraged,” he told Fred Ciampa of the Sporting News. “I love the game too much.”

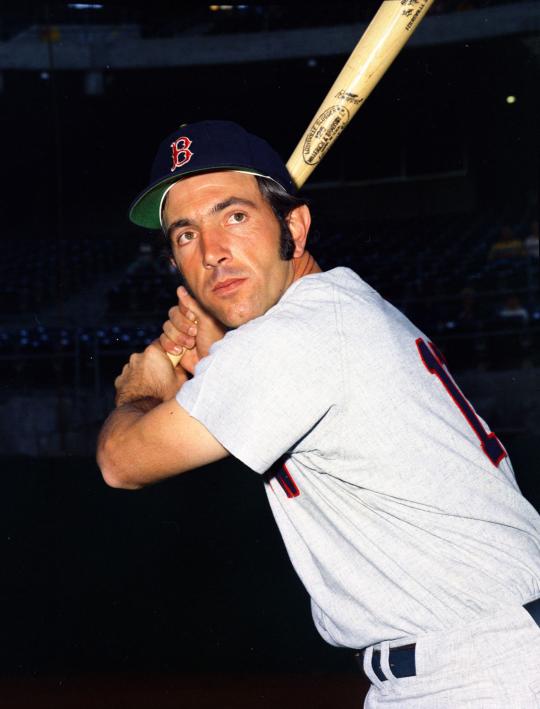

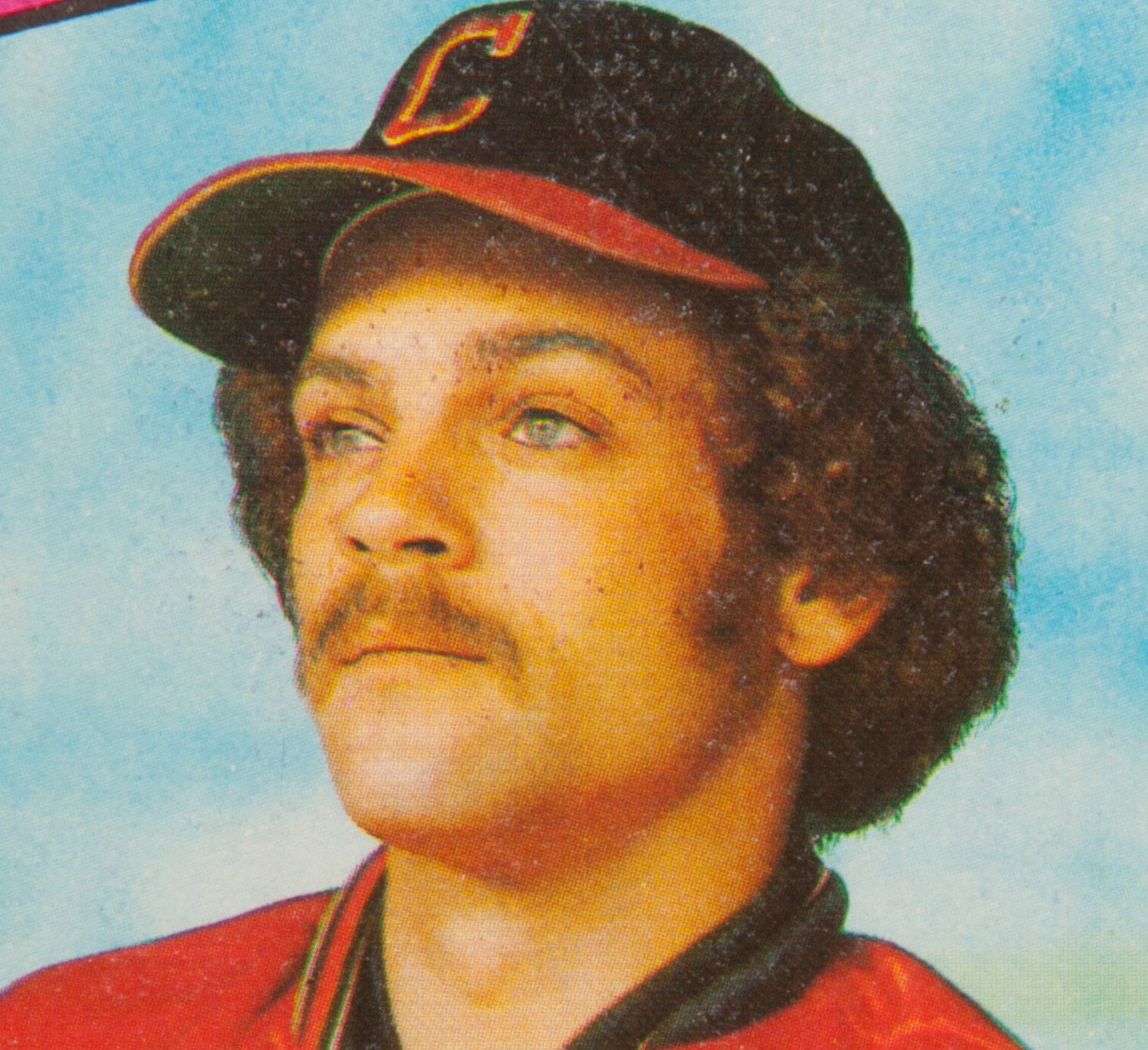

Now that he was in the major leagues, Montgomery faced competition from another young catcher, Jerry Moses. During the stretch run, the Red Sox gave Monty most of the playing time, putting him into 22 games and giving him 86 plate appearances. Given the chance to play, Montgomery struggled against American League pitching. He finished the season with only one home run, a .179 batting average, and an OPS of under .500.

That winter, Montgomery received some favorable news when he heard that the Red Sox had traded Moses, sending him to the California Angels as part of the Tony Conigliaro swap. Reporting to Spring Training in 1971, Montgomery seemed destined to be the Red Sox’ No. 1 catcher. But then just before the start of the season, the Red Sox complicated matters by acquiring veteran catcher Duane Josephson in a trade with the Chicago White Sox.

Just like that, Josephson became the Opening Day catcher. He would handle the majority of the catching chores for the Red Sox that season, but a few nagging injuries gave Montgomery some extra playing time as a backup. More significantly, he faced the looming arrival of Fisk, who was tearing up the minor leagues and would receive a late-season look-see from the Red Sox.

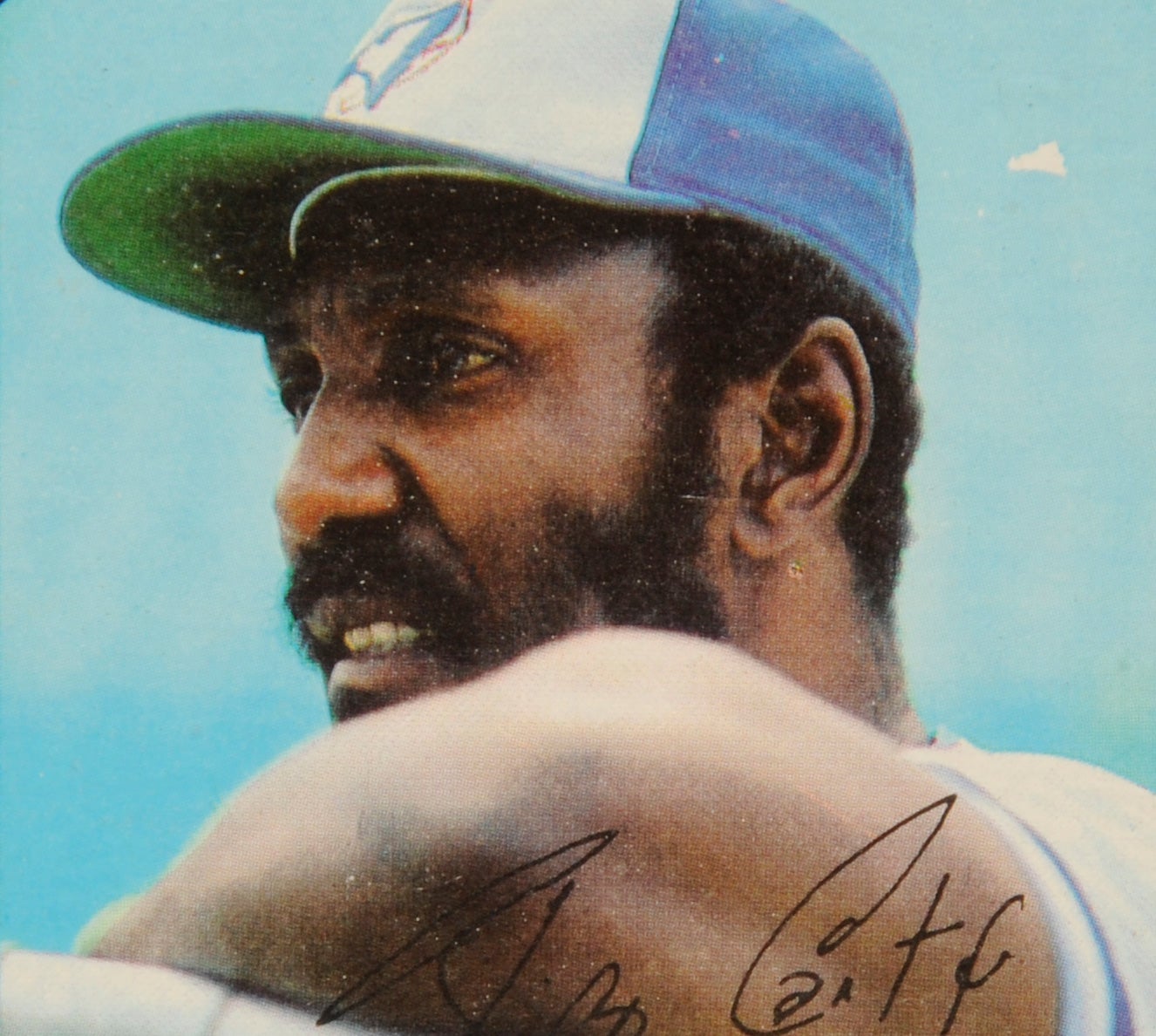

In 1972, Fisk took over the starting catching job and became an immediate star, earning a Gold Glove Award and winning American League Rookie of the Year honors. Montgomery settled in as his backup, hitting .286 but appearing in only 24 games. In the meantime, the Red Sox missed out on reaching the postseason by a half-game in the standings, a product of an unbalanced schedule caused by an early season strike by the Players’ Association.

As good as Montgomery was at handling the defensive chores of the catching position, he simply could not match Fisk’s ability as a hitter. So he settled for a role as the No. 2 catcher, which he did well. In 1973, Monty came to bat 128 times, batted .320, and slugged .563, giving the Red Sox an embarrassment of riches behind the plate.

Developing good rapport with his pitchers, Montgomery earned a reputation as the American League’s best backup catcher. Invariably, trade rumors swirled around him, with other teams that were desperate for catching help believing that Monty could start for them. Yet, Montgomery wanted no part of a trade, even if it meant an increase in playing time. He loved playing in Boston so much that he often told reporters that he preferred being a backup catcher for the Red Sox to being a starting catcher somewhere else.

In 1974, Montgomery received more playing time than expected. It was the result of a season-ending knee injury suffered by Fisk on June 28. Montgomery ended up playing in a career-high 88 games. With an OPS of only .625, Montgomery’s hitting fell well short of the Fisk standard, but his work behind the plate ingratiated him with the Red Sox’ pitching staff.

In 1975, Fisk and Montgomery reported to Spring Training expecting to resume their usual tag-team combination behind the plate. But Fisk broke his arm during an exhibition game, sidelining him for nearly the first three months of the season. Monty took over the No. 1 catching job and performed well, highlighted by four game-winning RBI. With Montgomery behind the plate, the Red Sox took an early lead in the American League East divisional race.

After Fisk’s return, the Red Sox retained that lead for most of the season, pushing them into a postseason matchup with the Oakland A’s. Montgomery did not play in Boston’s three-game sweep of the defending world champions, but did pick up one at-bat during a classic World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. He appeared as a pinch-hitter in Game 7, as the Red Sox lost the decisive game, 4-3.

As Fisk became more durable, Montgomery saw his playing time dwindle. Over the final four seasons of his career, he never appeared in more than 32 games, with the high point coming in his final season. Though his playing time had been reduced, Montgomery hit well off the bench, compiling a .300 batting average in 1977 and a career-best .349 in 1979.

He also drew the praise of his manager, Don Zimmer.

“He knows his job, and he goes out and does it,” Zimmer told Larry Whiteside for the Sporting News. “He does extra things. Nobody has to tell him how or when. He just does it. In my five years, he’s been a fill-in, a starter, a first baseman, a bullpen [catcher]…everything. You feel fortunate to have a guy like that on the club.”

Montgomery’s hitting in 1979 indicated that he had something left in the tank for 1980. Yet, he reported to Spring Training without the guarantee of a roster spot, in part because of the presence of a good catching prospect, Gary “Muggsy” Allenson. The Sox also had concerns about Montgomery’s age and his fading defensive skills. Ultimately, Boston decided to keep the younger Allenson as a backup, leaving Montgomery the odd man out. Late in the spring, the Red Sox released Montgomery, who decided to call it a career at the age of 35. As a result, Montgomery’s career spanned the entirety of the 1970s, but did not extend into the new decade.

After his playing days, the outgoing Montgomery became a popular broadcaster for the Red Sox on their flagship TV station, WSBK. He remained in the position through 1995, when WSBK dropped its coverage of Red Sox games. Now out of a job, Monty moved on to the world of private business. He has since returned to do some broadcasting, working as a color analyst on Pawtucket Red Sox minor league broadcasts. He also works for a marketing firm called Adventures in Advertising, where he is still involved with sales promotions.

All these years later, Montgomery is still occasionally asked about being the last major leaguer to step into the box without a helmet. The lingering interest surprises Montgomery, but he does take some pride in being a part of the game’s evolution of equipment. After his retirement from baseball, he donated his cap and protective plastic liner to the Hall of Fame, where it is currently on display in the “Whole New Ballgame” exhibit.

That artifact is a reminder that Bob Montgomery was the final player to step into a batter’s box without the game’s ultimate piece of protection.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum