- Home

- Our Stories

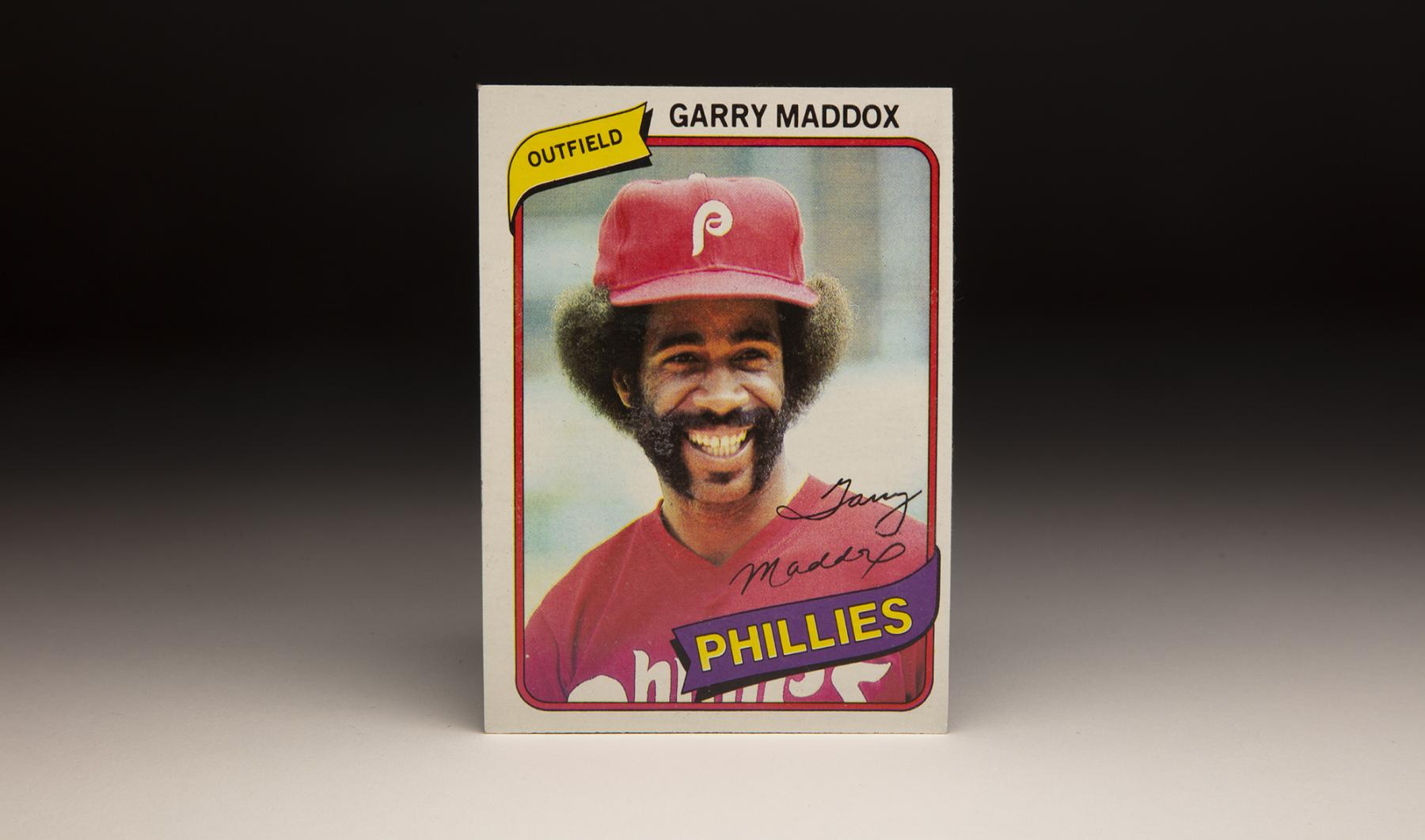

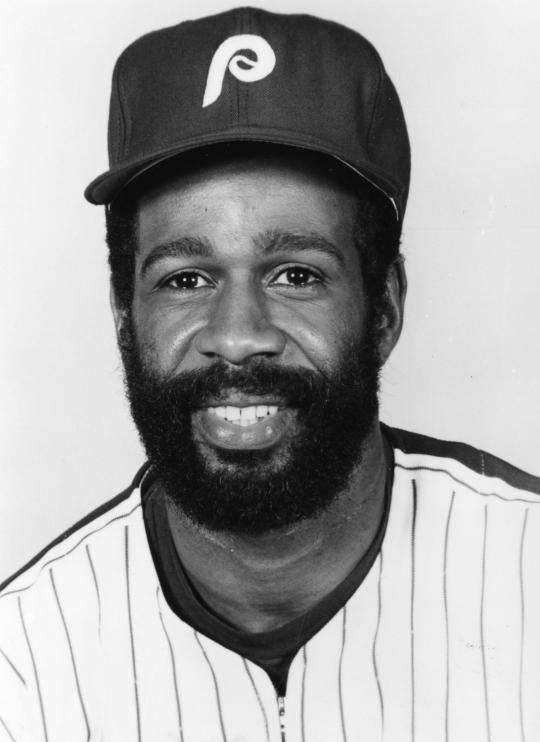

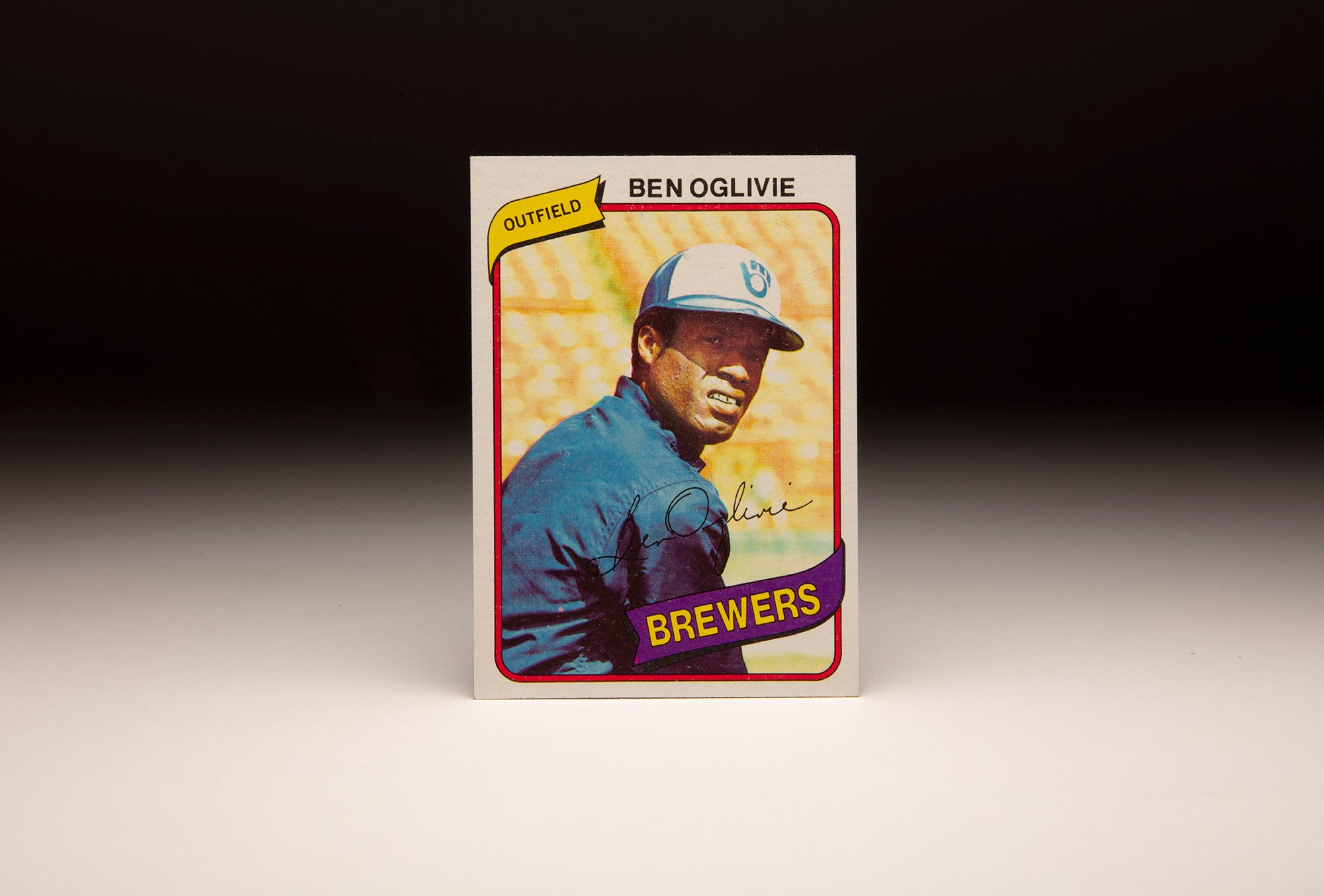

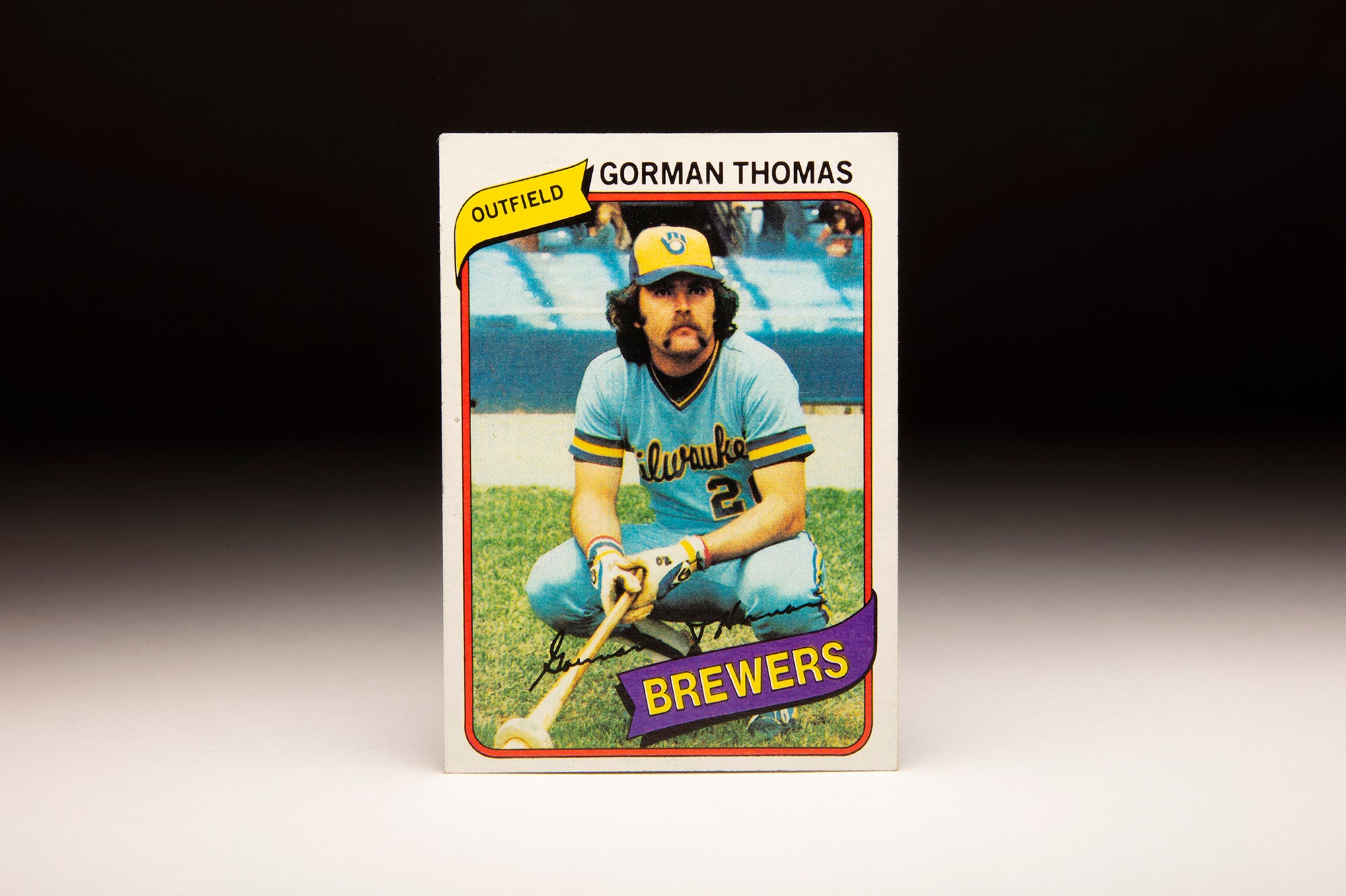

- #CardCorner: 1980 Topps Garry Maddox

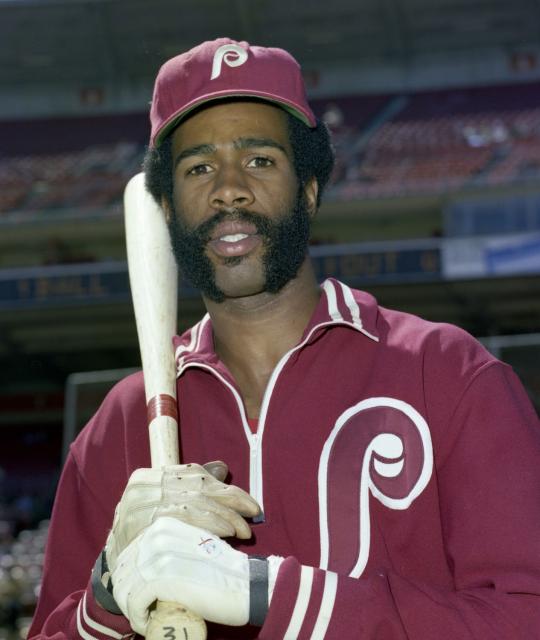

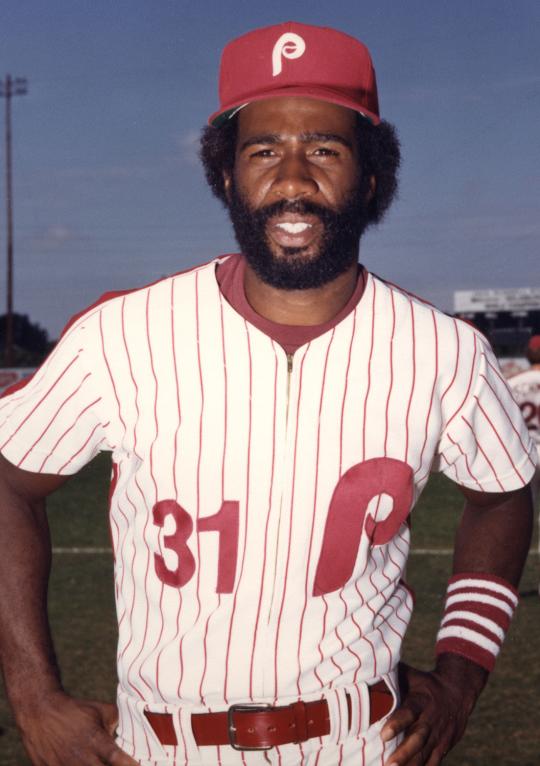

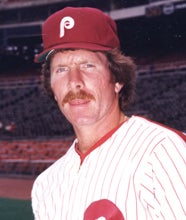

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Garry Maddox

He was an eight-time Gold Glove Award winner in center field, known as the Secretary of Defense and the inspiration for one of the greatest quotes an outfielder has ever earned.

But Garry Maddox may still be one of the most underrated defensive outfielders in the game’s history.

Consider Maddox’s three peak seasons as a defender – 1976 and 1978-79, according to the Defensive WAR metric. No center fielder in the 1970s had three seasons with at least a 2.1 dWAR, and Maddox’s 2.9 in 1979 was matched only once in the decade.

“Two thirds of the earth is covered by water,” wrote Philadelphia Daily News columnist Ray Didinger in a quote that has been repeated for decades. “The other third is covered by Garry Maddox.”

Born Sept. 1, 1949, in Cincinnati, Maddox moved with his family to the Los Angeles suburb of San Pedro while he was a youngster. The second oldest of nine children, Maddox played baseball throughout his youth and caught the attention of San Francisco Giants scout George Genovese, who convinced the team to take Maddox in the second round of the January 1968 MLB Draft.

Phillies Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Maddox was part of a group of Los Angeles-area super athletes that also included future big leaguers Jeff Burroughs, Enos Cabell and Darrell Evans.

“I think I (blossomed first),” Cabell, who played against Maddox at nearby Gardena High School, told the News-Pilot of San Pedro. “I was around before Garry was, but then we both graduated at the same time. The only difference was, I went away to college and Garry went into the service.”

Maddox appeared in 58 games for Salt Lake City of the Pioneer League in 1968 before earning a late-season promotion to Class A Fresno. But Maddox, tired of the long bus rides and low pay of a minor leaguer, left the game to enlist in the Army.

Soon, he was spending a 22-month tour in Vietnam.

“The scene over there was going to change you one way or another,” Maddox told The Catholic Advance in 1977. “Some guys became drug addicts. Others ran around with women. A friend of mine blew himself up with a hand grenade.”

While in Vietnam, Maddox was baptized a Catholic.

“As a kid, I never had any real contact with religion,” Maddox said. “Things were tough growing up. I can remember Christmases where eight of us got one volleyball to play with – one volleyball.”

While in Vietnam, Maddox learned that his father had suffered multiple heart attacks. He applied for a hardship discharge. To receive one, Maddox had to have a job waiting for him.

He called the Giants and asked for another chance.

“I think if I hadn’t gone into the service,” Maddox told The Catholic Advance, “there wouldn’t have been any more baseball for me. I personally think the experience helped mature me.”

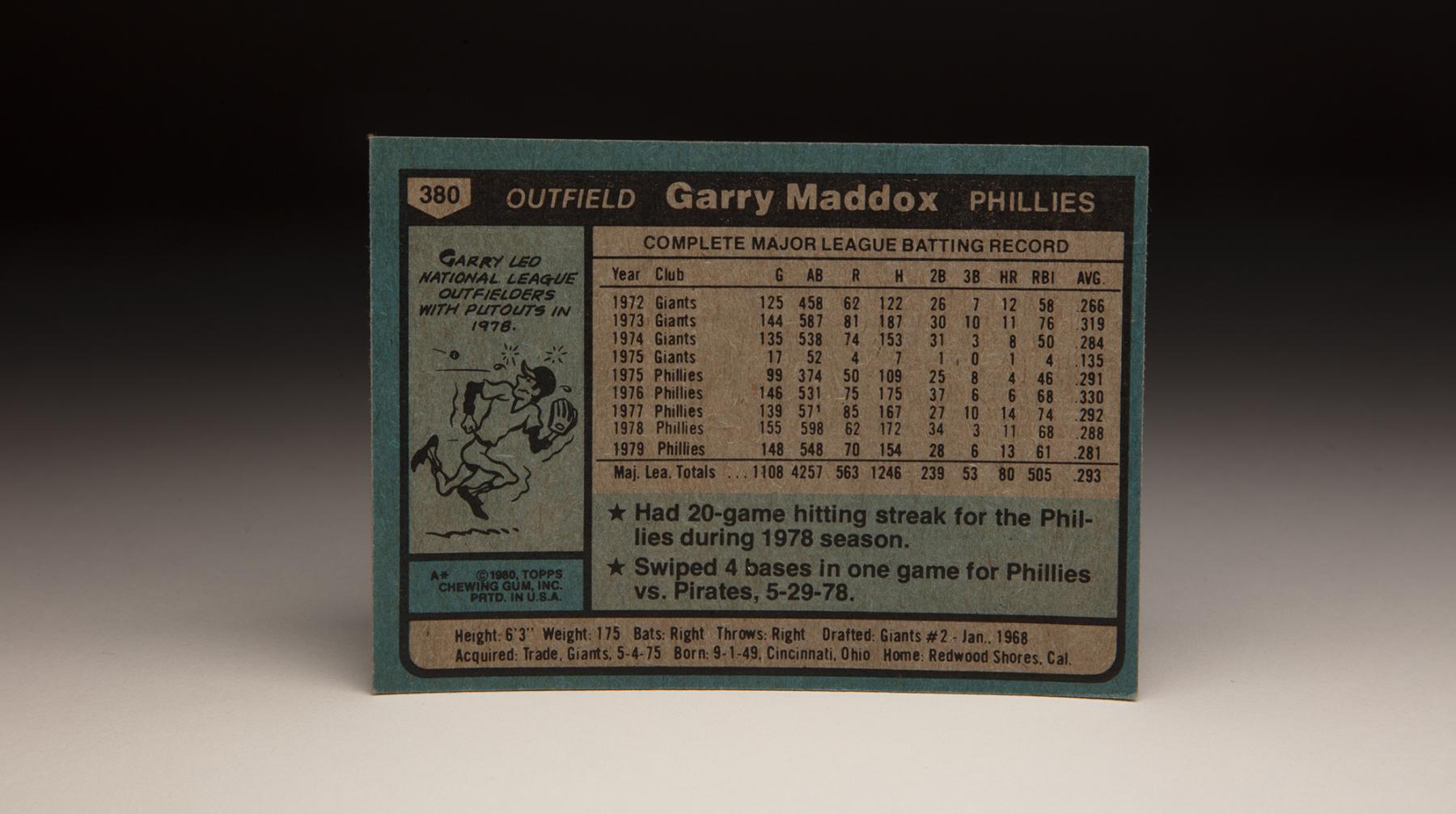

Back with Class A Fresno in 1971, Maddox tore through the California League – hitting .299 with 30 home runs, 106 RBI and 105 runs scored in 120 games. After hitting .438 with nine home runs and 22 RBI in 11 games with Triple-A Phoenix in 1972, Maddox was summoned to San Francisco.

He bounced from center field to left field and right field into June – following the May 11 trade of Willie Mays to the Mets – when Giants manager Charlie Fox put Maddox in center and left him there. Maddox ended the season hitting .266 with 12 homers and 58 RBI, becoming the first player other than Mays to start the majority of games in center field for the Giants since 1953 when Mays was in the military.

Maddox came out of the gate on fire in 1973, recording hits in 18 of the Giants’ first 19 games and pushing his batting average to .377 with a five-for-five performance against the Expos on May 26. Fox quickly moved him to the No. 3 spot in the batting order.

“He’s a natural for that spot with his speed and hitting,” Fox told the San Francisco Examiner.

Maddox finished the season with a .319 batting average (behind only Pete Rose and César Cedeño in the NL), 30 doubles, 10 triples, 11 home runs and 24 stolen bases. He battled a back injury in 1974 but still hit .284 with eight homers and 21 steals in 135 games.

“I just try to be consistent,” Maddox told United Press International in 1974. “I try to hit within my capabilities.”

But in the spring of 1975, Maddox was hobbled by an ankle injury and new manager Wes Westrum – who replaced Fox during the 1974 season – told the media that Maddox might begin the season in a platoon with newly acquired Von Joshua.

“It should be good for both their attitudes,” Westrum told the Sacramento Bee.

It wasn’t. And on May 4, the Giants sent Maddox to the Phillies in a one-for-one-deal for Willie Montañez.

“I feel it’s an even trade,” Phillies manager Danny Ozark told the Philadelphia Daily News, which pointed out that Montanez led the Phillies with 16 RBI while Maddox was hitting just .135. “We’re getting a guy with extraordinary speed with doubles and triples power.”

Montañez lasted 13 months in San Francisco before he was traded to the Braves. Maddox became a legend in Philadelphia.

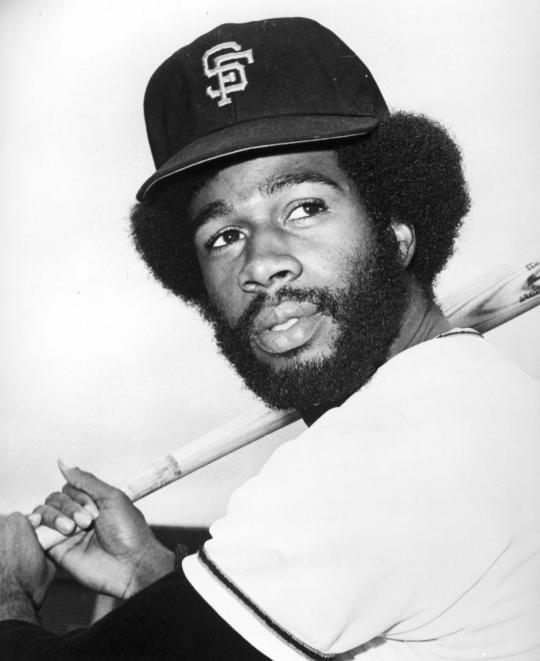

Maddox missed almost the entire month of June with a knee injury, but a .369 average in July helped raise his season-ending mark to .272. And patrolling the wide spaces of the Veterans Stadium outfield – between Greg Luzinski and Jay Johnstone – Maddox earned the first of eight straight Gold Glove Awards.

In 1976, the Phillies advanced to the playoffs for the first time in more than a quarter century by winning the National League East title. Maddox hit .330 – third-best in the NL – with 75 runs scored, 37 doubles, 68 RBI and 29 steals while taking his defense to a new level. The Phillies were swept in the NLCS by the Reds – Maddox was hampered by an injured left wrist – but their center fielder finished fifth in the National League Most Valuable Player voting, two places behind teammate Mike Schmidt.

Late in the 1976 season, Maddox signed a new five-year deal with the Phillies.

“I’ve never seen a better center fielder,” Phillies shortstop Larry Bowa told the Philadelphia Daily News. “He’s the key to our club. He’s our most valuable player.”

In 1977, Ozark moved Maddox to the leadoff spot after Dave Cash took his 189 hits and left for Montreal as a free agent. Maddox did not like hitting leadoff, however, and did not hesitate to voice his opposition.

“I’m a free swinger,” Maddox told the Associated Press, “and I don’t want to be restricted.”

Maddox was hitting .276 in late June when Ozark returned him to the No. 6 slot in the batting order, moving Bake McBride into the lead off role. From there, Maddox hit .307 – finishing the year with a .292 average, 14 homers and 74 RBI as the Phillies once again won the NL East.

This time, the Dodgers defeated Philadelphia in the NLCS. Maddox missed the first two games after fouling a pitch off his leg in the final game of the regular season, then went 3-for-7 in Games 3 and 4.

Entering his age-28 season in 1978, Maddox was recognized as one of the game’ top all-around outfielders. He appeared in a career-best 155 games that season, hitting .288 with 11 homers, 68 RBI and 33 stolen bases. He tallied a 20-game hitting streak from Aug. 26-Sept. 15.

The Phillies won their third straight NL East title but lost in their third straight trip to the NLCS.

In Game 4 – with the score tied at three and the Dodgers leading the best-of-5 series 2-games-to-1 – Tug McGraw retired the first two batters in the bottom of the 10th before issuing a walk to Ron Cey. Dusty Baker followed with a sinking line drive to center that Maddox quickly approached and seemed ready to catch. But the ball clanged off his glove for an error, putting Cey at second base.

Bill Russell then singled to center, and the ball scooted under Maddox’s glove as he tried to quickly pick it up and throw home. Cey scored uncontested, giving the Dodgers the series win.

“The ball was right in my glove,” Maddox told the Philadelphia Inquirer of Baker’s line drive. “It was not a tough play, just a routine line drive. It cost us a shot at being World Champions.

“It’s something I’ll never forget the rest of my life.”

Maddox posted a typical season in 1979: .281 batting average, 13 homers, 61 RBI and 26 steals. But the Phillies fell to fourth in the NL East, prompting management to replace Ozark with scouting director Dallas Green late in the season.

Green’s no-nonsense approach paid dividends in 1980 when Philadelphia returned to the playoffs. Maddox, however, clashed with Green on occasion and hit just .259 – the worst average of his career.

The playoffs, however, would be a different story.

In Game 5 of a hotly-contested NLCS vs. the Astros, Maddox found himself at the plate in the top of the 10th with the score tied at seven and Del Unser on third base with two outs. Maddox lined a double to center off Frank LaCorte, bringing home the go-ahead run that stood up when Dick Ruthven retired Houston in order in the bottom of the frame – with Maddox recording the final two putouts.

“You try to keep from getting choked up,” Phillies owner Ruly Carpenter told the News Journal of Wilmington, Del., in the clubhouse after the game, “but I choked up when Garry Maddox caught the final out. There were a few tears in my eyes.

“I know this is a very, very important moment for Garry Maddox. You have to think back to (Game 4 in the 1978 NLCS). I know how he felt that day.”

Maddox was carried off the field by his teammates after recording the final out, his right hand thrusting the final-out ball in the air.

“Tonight is one of the most exciting moments of my life,” Maddox said. “This championship has been a long time coming – for me, for my teammates and for the fans of Philadelphia.”

But the Phillies weren’t finished. In the World Series against the Royals, Maddox hit just .227 but Philadelphia won the title in six games – the first world championship in franchise history.

It would be the unquestioned peak of Maddox’s big league career.

Maddox was hitting .292 when the strike interrupted the 1981 season – but a .225 average over his final 43 games dropped his season mark to .263. He made just two appearances in the NLDS vs. the Expos as Lonnie Smith started all five games in center field. Maddox did not appear in Philadelphia’s 3-0 loss in Game 5 that ended the Phillies’ season.

But with Green having moved on to the Cubs and Smith traded to the Cardinals, Maddox reclaimed his traditional starting center field spot in 1982. He hit .284 with 61 RBI in 119 games and won his eighth and final Gold Glove Award.

He transitioned into a bench role over the next three seasons, helping the Phillies advance to the 1983 World Series – with his eighth-inning homer in Game 1 giving Philadelphia it’s only victory of the Fall Classic.

He contributed off the bench in 1984 and 1985 – he tied a center fielding record with 12 putouts in a 12-inning game against the Pirates on June 10, 1984 – before a back injury severely limited his ability to chase down balls in 1986. With his finances in order thanks to some shrewd investing, Maddox retired on May 7, 1986.

“I’m going to have a lot of good years after baseball,” Maddox told the Morning Call in Allentown, Pa., “and I’d like to spend them with my family and in good health. You see and read stories about people who played that one game too many, or the boxer who fought one fight too many. I didn’t want to risk that.”

Maddox – who enrolled at Temple University late in his playing career – had long been involved with community-building efforts, having started supporting the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic in 1977 and joining its board of directors in 1983. By 1985, Maddox had raised more than $500,000 for the organization.

In 1986, Maddox won MLB’s Roberto Clemente Award for his charitable efforts. In 1987, the Phillies hired him as a broadcaster – and he spent several years with the team in the TV booth.

But for a player who faced all the challenges baseball and life can offer, nothing topped winning the World Series.

“To sit there and look up and see the confetti fall,” Maddox said of the parade following the World Series win in 1980, “you say, ‘Hey, I’ve seen this on TV when the astronauts returned.’

“That was just a tremendous feeling.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum