- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps Bobby Brown

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Bobby Brown

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

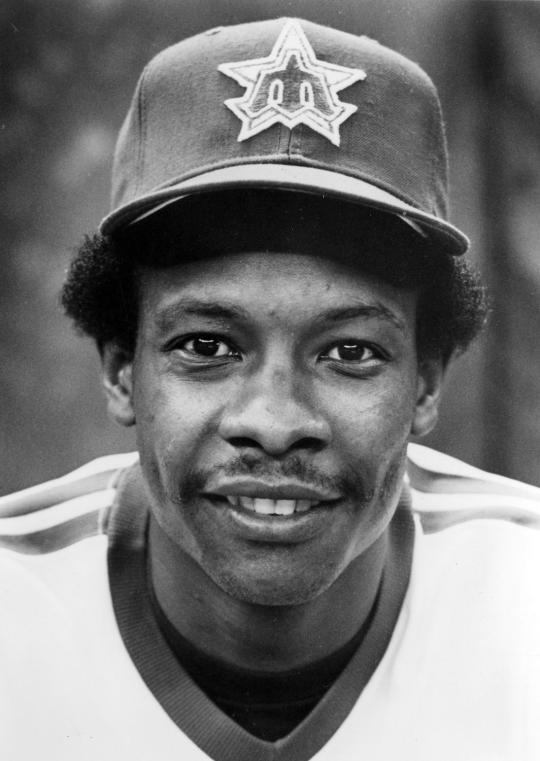

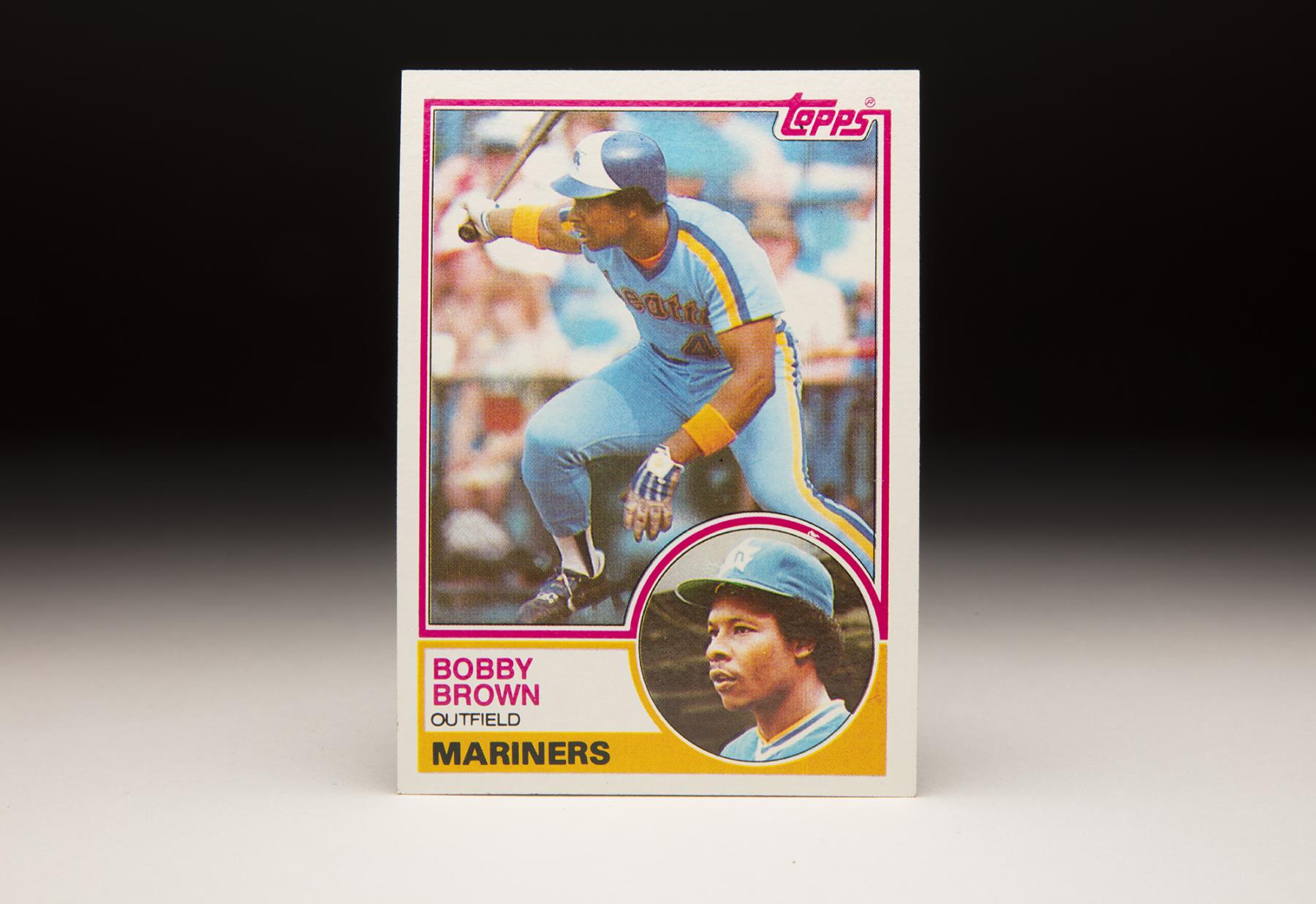

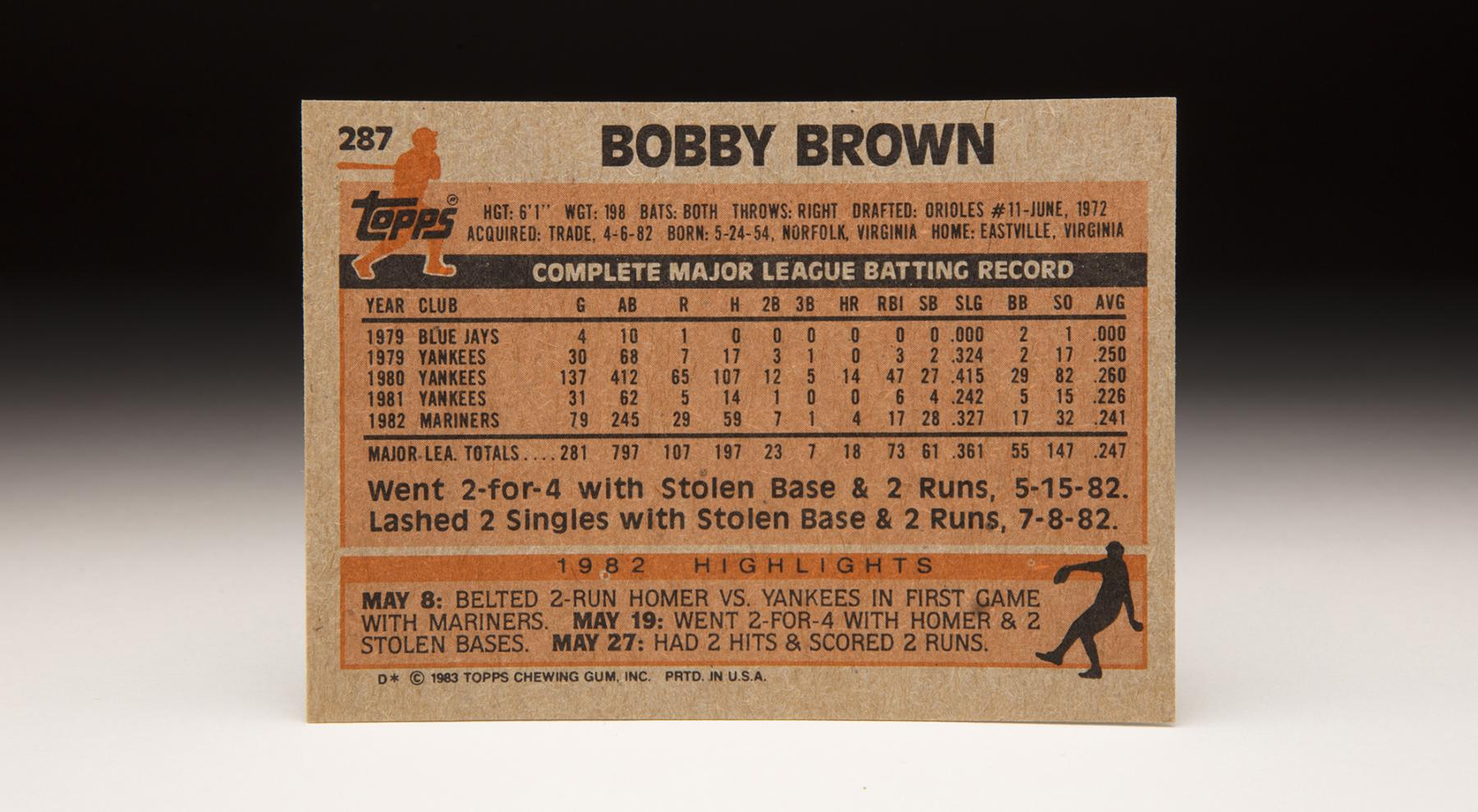

Perhaps responding to newfound competition coming from Donruss and Fleer, the Topps Company put out one of its best sets in years with its 1983 release. With two photos on each card and a simple but attractive design, Topps created a visually stunning set of cards. Among my favorites from the ’83 set is Bobby Brown’s card. Instead of showing us the standard shot of Brown waiting for his pitch while at bat, the card shows him in the middle of his swing, which looks a bit awkward. It’s hard to say whether this was a productive swing, but Brown does look a bit off balance; he might have been out in front of one of those dreaded curveballs that made life difficult for him at times in the big leagues. Perhaps the card should serve as a reminder of the complexity of each swing, of just how much goes into the process of hitting a ball. The action shot is also clear enough to show us Brown’s face, revealing a grimace in the middle of the swing.

It’s another reminder of how hard it is to hit in the major leagues; I imagine that many hitters find themselves grimacing while trying to square up a rounded bat against a rounded ball that is traveling nearly double the speed limit of an average motor vehicle.

For a relatively obscure player like Brown, hitting in the big leagues was never particularly easy. He was a terrific minor league player, an All-Star and league MVP, the owner of a batting championship, and a dangerous basestealer. But outside of one season in 1980, Brown found similar success in the big leagues elusive. Of course, that didn’t stop him from having fun along the way, and gaining a newfound fan in this writer.

Brown is exactly the kind of player with whom I can identify and sympathize. His path to the majors was long and twisted, marked by so many fits and starts that his level of perseverance becomes admirable. No one would have blamed him for quitting the game, but Brown chose to keep toiling. Eventually, his patience and work ethic paid off.

Eleven years before Brown’s 1983 Topps card hit the shelves, his professional career began with the Baltimore Orioles’ organization. Born Rogers Lee Brown, he shared a first name with Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby, but no one called him by that name; it was always “Bobby.” The Orioles selected him in the 11th round of the 1972 amateur draft and assigned the left-handed-hitting speedster to Bluefield, their affiliate in the Class A Appalachian League. Brown struggled in his rookie stop, but showed some promise the following summer with Miami of the Florida State League. That’s where Brown stole 18 bases and hit .283, albeit with little power.

In 1974, Brown started to blossom at Lodi of the California League. He batted .301 and hit eight home runs. He repeated Lodi in 1975, before finally receiving a late-season call-up to Double-A ball. The Orioles then invited Brown to Spring Training in 1976.

Just before the start of the ’76 season, the Orioles surprisingly released Brown. He remained out of work for five weeks, before the Philadelphia Phillies came calling with a minor league offer. For some reason, the Phillies gave Brown a return assignment to Single-A ball. Not surprisingly, Brown dominated the Carolina League, hitting .349 with a .398 on-base percentage and 42 stolen bases.

In 1977, the Phillies gave Brown a fulltime shot at Double-A. He hit .290 with moderate power, earning a call-up to Triple-A Oklahoma City in midsummer. Brown took well to his first taste of Triple-A ball, where he batted .314 with a .352 on-base percentage.

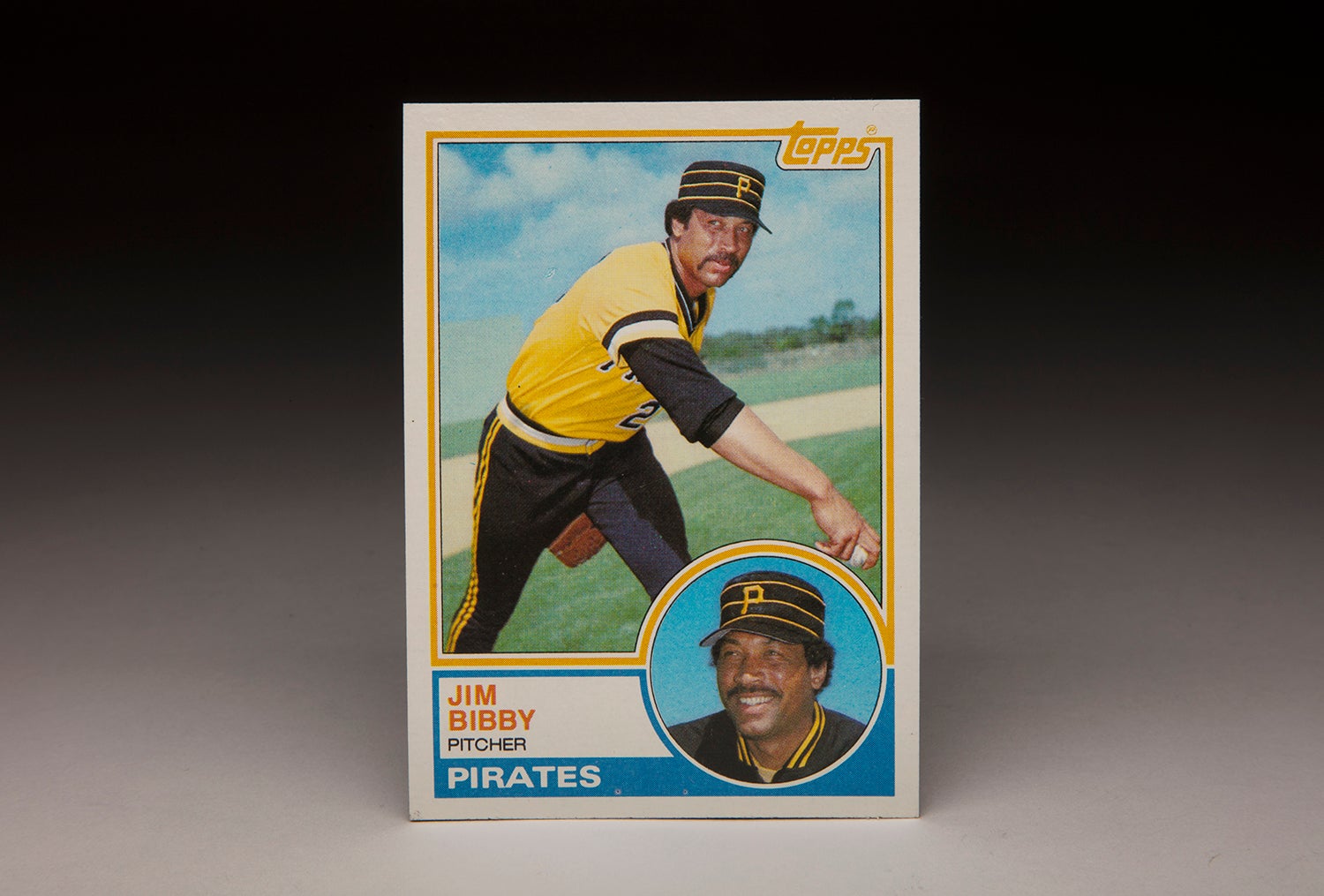

As well as Brown played in Oklahoma City, he faced roadblocks in the Phillies’ outfield. With Greg Luzinski, Garry Maddox and Bake McBride all entrenched as starters, and with Downtown Ollie Brown, Jay Johnstone, and Jerry Martin all capable backups, there was no way for Brown to break through and make the major league roster. So he went back to Triple-A to start the 1978 season; after a good 50-game start, the Phillies included him in a deal along with Jay Johnstone, sending them to the New York Yankees for former relief ace Rawly Eastwick.

Like the Phillies, the Yankees had an overcrowded outfield. With no room in the Bronx, the Yankees assigned Brown to their Triple-A affiliate in Tacoma, Wash. Over a 66-game tenure in Tacoma, Brown hit .310 with 10 home runs. That kind of performance would have seemed likely to garner Brown a spot on the 40-man roster that winter, but a crowded Yankee outfield dictated otherwise. The Yankees left him exposed to the Rule 5 draft, allowing the rival New York Mets to select him.

The stipulations of the Rule 5 draft helped Brown make his major league debut in 1979, but in a circuitous way. The Mets, who needed outfield help, watched Brown hit .318 in Grapefruit League play. For some reason, that didn’t impress the Mets, who placed him on waivers in an effort to send him to Triple-A Tidewater.

But the Toronto Blue Jays put in a claim and placed him on their major league roster. After seven years of minor league struggles, Brown would finally make his big league debut as a Blue Jay.

As a recent expansion team, the Blue Jays lacked frontline outfield talent, but they gave Brown little chance to play. Now experimenting with switch-hitting in his quest to become an everyday player, Brown appeared in only four games, going hitless in 10 at-bats. Concerned about his difficulties in hitting breaking pitches and wanting to make room on the roster for veteran slugger Bob Robertson, the Jays moved on.

In late April, they sold Brown back to the Yankees, the defending world champions. Returning to his old organization, Brown also found himself returning to the minor leagues. Initially, the Yankees loaned him to a team in the short-lived Inter-American League. He spent five days with the San Juan franchise before the Yankees assigned him to their Triple-A affiliate, now situated in Columbus, Ohio. Once again, he dominated the minor leagues, hitting .349.

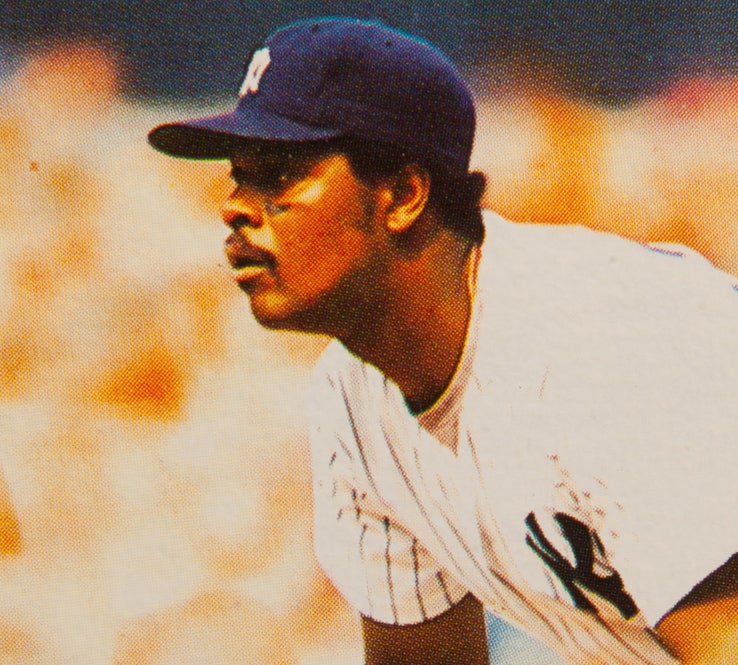

In 1979, the Yankees suffered a World Series hangover. They also had an aging roster, with many of their veterans becoming susceptible to injury. One of those veterans was Mickey Rivers, who went down with an injury. Desperately needing outfield reinforcements, the Yankees eventually called on the switch-hitting Brown, who was having a banner season at Columbus, where he was named the International League’s co-MVP.

In the Bronx, Brown received some playing time in center and left and also did some work as a DH. Appearing in 30 games, Brown hit .250, but with no home runs. He continued to have problems hitting the curveball. Late in 1979, the Yankees traded Rivers to Texas. After the season, they made a blockbuster trade with Seattle for Ruppert Jones, a budding center field star.

Once again, Brown seemed doomed to life as a spare part in the Bronx. But the Yankees felt that Brown, an impressive physical specimen with speed and power, had talent. Yankees general manager Gene Michael, who had managed Brown in the minor leagues, said that the young outfielder had gained an unfair reputation as a troublemaker. “I found out it wasn’t true at all,” Michael told The New York Times. To the contrary, Brown played the game all-out and worked hard.

When Jones came down with an intestinal ailment that put him on the sidelines for six weeks, Brown received an opportunity to play. Later in the season, Jones suffered a season-ending shoulder separation. In the meantime, Brown handled most of the center field chores for the Yankees – and showed ample reason for Michael’s confidence in him.

Brown ended up playing 137 games in 1980. He hit 14 home runs, batted a respectable .260, stole 27 bases and showed good range in the outfield. Yes, he had flaws in his game. He lacked a strong throwing arm for center field. At the plate, he rarely walked. As a right-handed batter, he didn’t hit much. But his power and speed added some life to the Yankees, who would win 103 games that season.

Just as significantly, Brown brought hustle and enthusiasm to the Bronx. Playing the game with a rah-rah style and an ever-present smile, he became a familiar sight offering up congratulatory high fives to his teammates after they scored runs. He also earned a nickname, “Uptown” Bobby Brown.

To a young fan like me, Brown became a delight to watch all season long. For that one summer, he became my favorite Yankee.

Brown’s on-field exuberance echoed his exchanges with the media. During the 1980 season, he told Mike Lupica of the New York Daily News that he felt no bitterness toward the game for the many setbacks he had endured in trying to make the major leagues. “Baseball is beautiful for me all the time,” Brown told Lupica. “Look at me. I’m the same crazy every time you see me. The game hasn’t done nothing to me. Maybe individual decisions have held me back. But I’ve got no quarrel with baseball.”

Still only 26 years old, Brown looked like he might remain a Yankee mainstay. Prior to the 1981 season, he paid a visit to Harry Walker, the head coach at the University of Alabama-Birmingham and the former manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Walker had once helped transform Matty Alou into a batting champion. “I saw what he had done with other guys,” Brown told Murray Chass of The New York Times. “I needed to learn something that Bobby Brown could do. I learned to wait on the ball. I think last year I tried to do more with the ball than I should have. I learned to use my hands instead of my body so much.”

Unfortunately, Brown’s work with Walker did not pay off tangibly during the 1981 season. During Spring Training, the Yankees traded Jones to San Diego for Jerry Mumphrey, who became the starting center fielder, once again relegating Brown to a backup role. At one point, Brown went back to Triple-A. For the Yankees, he played in only 31 games of the strike-shortened 1981 season. He batted .226 without hitting a single home run. Coming after his breakthrough season of 1980, the new year was one of misery and disappointment for Brown.

The Yankees brought Brown to Spring Training in 1982, but he would not break camp with the organization. Just before Opening Day, the Yankees made Brown the dreaded “player to be named” later in a trade, sending him to the Mariners to complete an earlier deal for left-handed pitcher Shane Rawley. Just like that, Brown’s Yankees career was over.

With the Mariners, Brown received a chance to play when Dave Henderson went on to the disabled list in May. For the most part, Brown became a platoon outfielder, splitting his time with Bruce Bochte in left field. He stole 28 bases, but his hitting lagged behind, as evidenced by a .614 OPS. Brown returned to the Mariners’ spring camp in 1983, but he did not play well, failing to make the Opening Day roster. Toward the end of March, the Mariners released Brown.

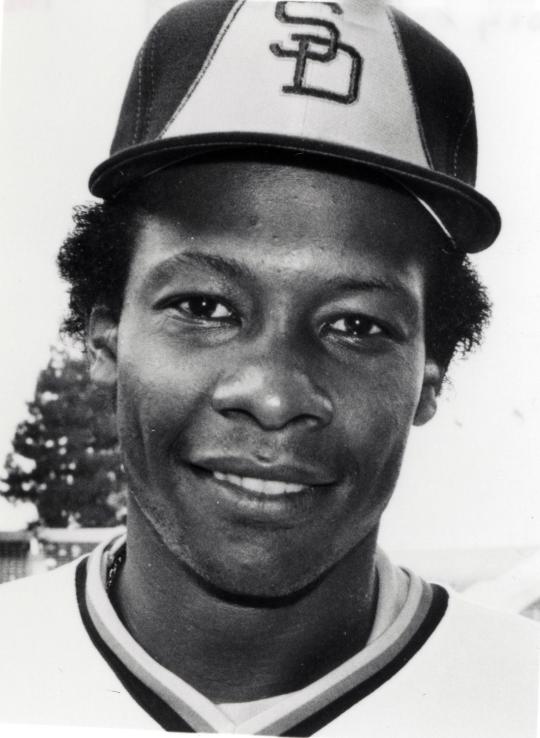

It didn’t take long for Brown to find work. In mid-April, the San Diego Padres signed him to a minor league contract. After a stint at Triple-A Las Vegas, Brown earned a promotion to San Diego in midsummer. His new manager, Dick Williams, took a liking to him and used him as a sometime starter in left field and as a backup to his onetime Yankees teammate, Ruppert Jones, in center.

Brown played decently in his new role, posting an OPS of .716 and stealing 27 bases. With Tony Gwynn, Kevin McReynolds and Carmelo Martinez entrenched in the Padres’ outfield in 1984, Brown became a fourth outfielder. His hitting tailed off somewhat, but he remained a threat on the basepaths and capably filled in defensively at all three outfield spots.

As a team, the Padres won the National League West and the pennant, earning themselves a World Series berth against the Detroit Tigers. With McReynolds hurt, Brown took over in center field for the Series. He played in all five games, but flailed against Tigers pitching, picking up only one hit in 15 at-bats. The Padres fell short of the title, losing in five games to the more talented Tigers.

Brown returned to the Padres in a similar role in 1985, but his hitting bottomed out. He finished the season with a .155 batting average and no home runs. The Padres brought him back for Spring Training in 1986, but Williams’ departure as manager signaled that a change might be coming.

When the Padres acquired outfielder Marvell Wynne late in the spring, Brown approached the team’s general manager, Jack McKeon. “What’s the deal?” Brown asked, according to the Los Angeles Times. “Are you going to release me?” McKeon admitted that he was thinking about it, but couldn’t give a firm answer. Brown replied, “If you’re gonna release me, release me now.” A few days later, McKeon obliged.

Brown was only 31, but he found no takers for his services. So he began life after baseball, concentrating his efforts on his company, Major League Dairies, which he co-founded with former teammate Jerry Mumphrey. Placing several franchises around the country, Brown distributed milk and dairy products nationwide. Not much has been written about Brown since then. Like many former major leaguers who were not stars, he has become something of an obscurity, a forgotten figure. But I won’t forget about Bobby Brown and how he made that summer of 1980 so wonderful. As Brown once said, “Baseball is beautiful to me.” The same could be said of Bobby Brown.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame