- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps Rudy May

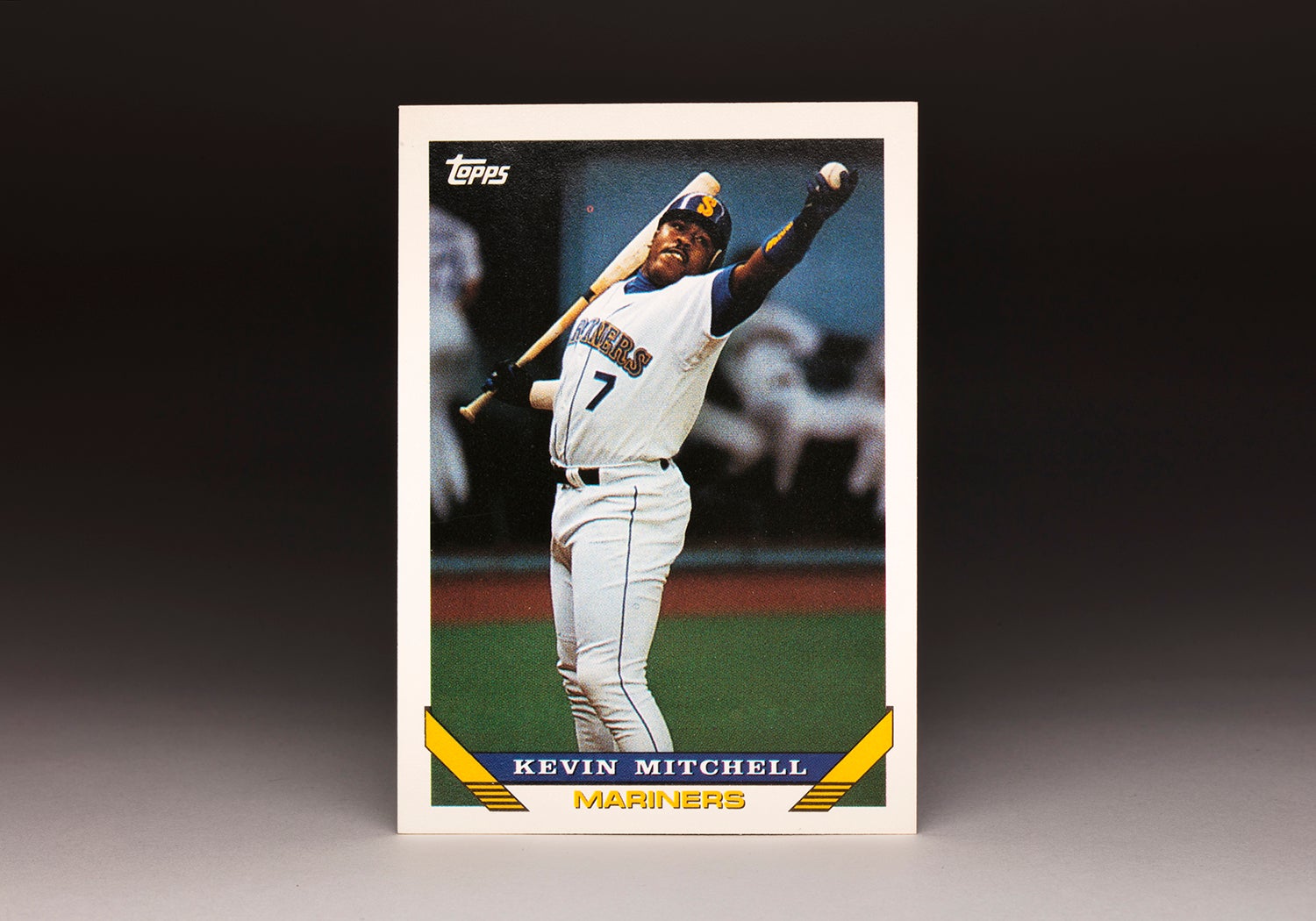

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Rudy May

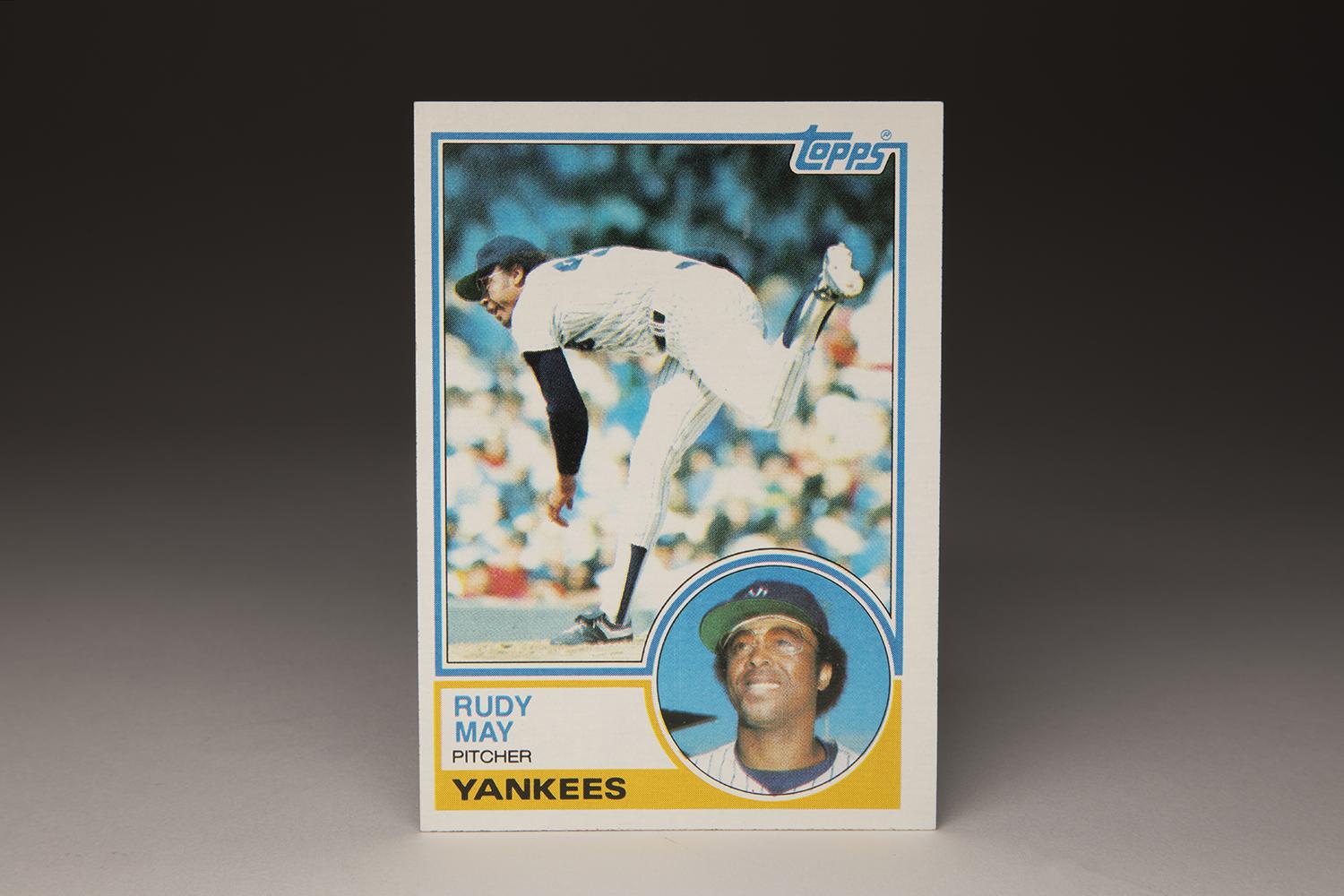

Rudy May’s action-packed 1983 card captures him just the way that I remember him. A stylish left-hander, May had a very smooth motion, with a distinctive and balanced finish, which is quite evident on this Topps card. The inset portrait, which was characteristic of all of the 1983 cards, also gives us a good look at May, from his oversized, tinted glasses to his slightly outsized Afro.

At a time when the game still had a considerable number of African-American pitchers, May always stood out, from his bespectacled look to his long, lean frame. It was befitting of his nickname: The Dude.

While it’s hard to portray motion on a baseball card, the 1983 version of May, along with his 1971 and 1980 editions, gives us a glimpse into his suave throwing manner. I loved to watch May pitch. He was not just style, but substance, a quality left-hander who always seemed to be in high demand. He had a good fastball and a better curveball. His curve became a devastating weapon – a twisting snake of a pitch that rendered even Hall of Fame hitters to a state of helplessness.

Thanks to that curveball, May became a good pitcher for the bulk of his career, but he took a circuitous route to the major leagues. It was an interesting path to say the least. Originally signed by the Minnesota Twins as an amateur free agent in 1962, he reported to Spring Training in Fernandina Beach, Fla., where he experienced culture shock of the worst kind.

“I got into a little bit of trouble because I was the only black player from the West Coast,” May told sportswriter Jeff Pearlman in 2014. “I didn’t know that I was not conducting myself as I should have been. For instance, the clubhouse was segregated. The whites were on one side and the blacks were on the other … and I was there a whole week before I realized that. I didn’t know. One of my teammates told me, ‘Why are you going in the front door of the clubhouse? Why are you drinking out of the fountain? You’re not supposed to do that. There’s a bucket in the back for us to drink out of.’ ”

From there, the Twins assigned May to a team in Bismarck, N.D., but he would never come close to pitching in the Twin Cities. After his first season of professional baseball, he was selected in the old first-year player draft, a procedure that has long since fallen off the books. The Chicago White Sox selected him from the Twins, but May would never see the light of day in Chicago either. After one season in the White Sox’ minor league system, the club parted ways with the hard-throwing left-hander, sending him to the Philadelphia Phillies for catcher Bill Heath.

Unlike his time in the Twins and White Sox’ organizations, May would never even pitch in the Phillies’ minor league system. That same winter, only two months after being traded to Philly, May found himself on the move again. The Phillies traded him and the wonderfully named first baseman, Costen Shockley, sending them to the California Angels for colorful left-hander Bo Belinsky.

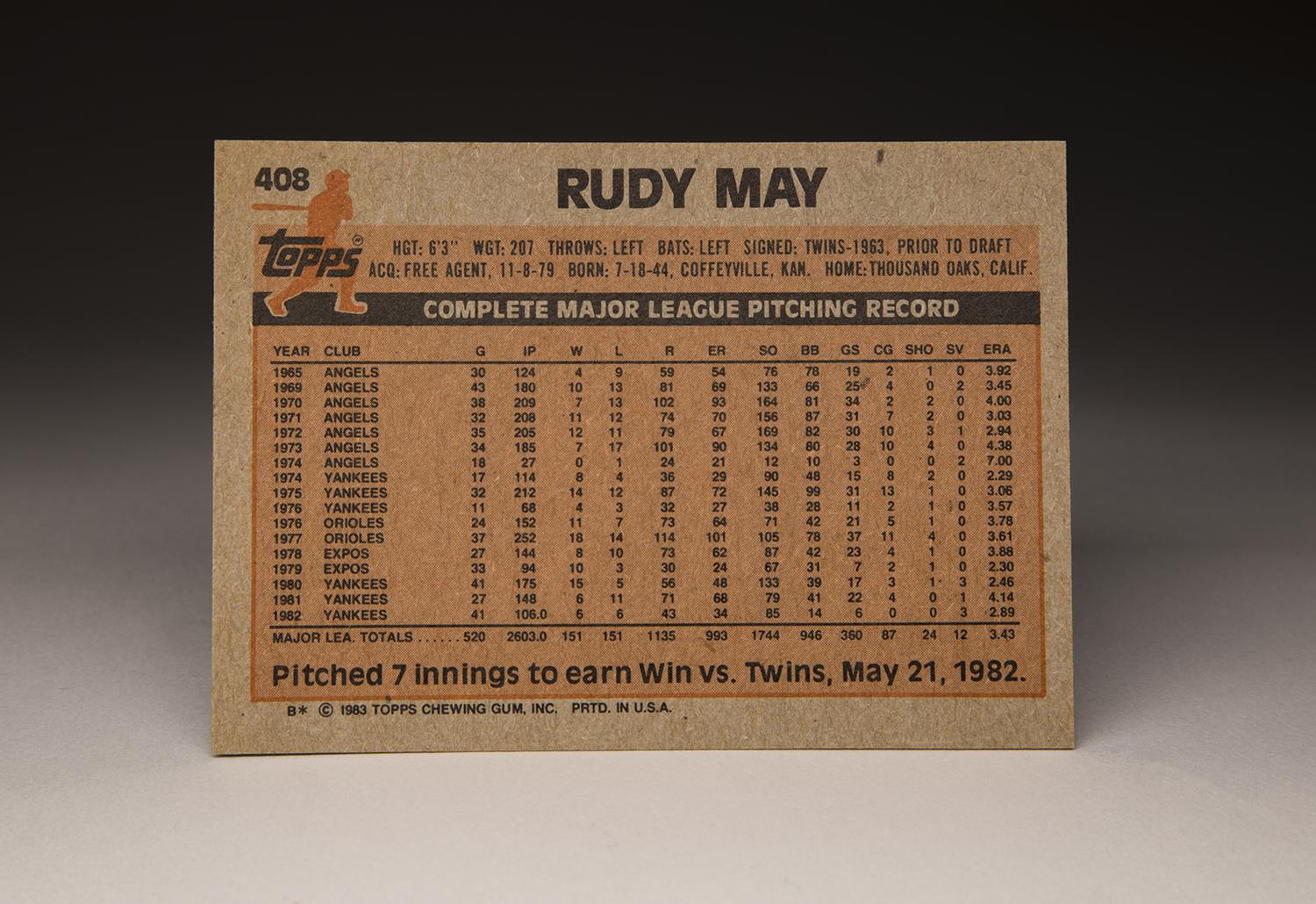

It was a steal of a trade for the Angels, since Belinsky was past his prime. As a recent expansion team, the Angels needed young talent – and lots of it. The following April, they brought May to the major leagues. By the time he made his debut in ’65, he had already been under contract to four organizations.

The Angels used May as a combination starter and reliever. At times, he looked brilliant, but he also struggled with his control. Over a span of 124 innings, he walked 78 batters and struck out 76, never a good ratio for a pitcher.

Given his up-and-down performance, the Angels realized that May needed more time in the minor leagues. They sent him back to Triple-A, leaving him there for three solid seasons.

During the spring of 1968, May felt pain in his pitching arm. One of the Angels coaches, Hall of Famer Joe Gordon, sat down with May and told him that he needed to take the mound and pitch, even if it meant working through the pain. (Such advice would likely not happen in today’s game, but such an old school approach typified baseball in the 1960s.) May followed the advice and struggled in his first inning, but by the second inning, his arm felt better. He went on to strike out six batters in a row, the harbinger of a good season to come at Triple-A San Jose.

By 1969, the Angels finally felt that May was ready. He would soon establish himself as a solidly effective starting pitcher, but it did not happen overnight. In 1970, a frustrated May sought help from a psychiatrist, something that ballplayers rarely did in that era. Seeking help from a psychiatrist was practically considered taboo for athletes of the 1960s and ’70s, but May didn’t care about those misconceptions.

“My wife and I put our heads together and tried to figure out what to do,” May told Angels beat writer Dick Miller. “Confidence is 50 percent of pitching, so we decided I would go to a psychiatrist to find out why I had trouble.”

May, who struggled with runners on base, met with the psychiatrist for 11 weeks. The talks helped May deal better with pressure situations, making him a far better pitcher in the process.

The results started to manifest themselves fully in 1971, when May posted a double-figure victory total while keeping his ERA at 3.02. On a team that became wracked with a series of controversies, which earned the club the nickname “Hell’s Angels,” May stood out as both a standout pitcher and a voice of reason. May would pitch even better in 1972, lowering his ERA to 2.94 while striking out 169 batters in 205 innings. He won only 12 games that summer, but that was mostly due to a lack of run support from the subpar Angels offense. May’s success stemmed from three pitches: a good fastball, a quality change-up, and a knee-buckling curveball. It was May’s curve – one of the five best curves in either league – that stood out above the rest.

After his career-best pitching in 1972, May took a tumble in 1973. His ERA soared to 4.38. A poor start to the following season doomed his tenure with the Halos. At the June 15 trading deadline, the Angels hastily settled on a cash transaction, selling the veteran left-hander to the Yankees for the sum of $100,000.

The Yankees felt they had pulled off a steal – and they were right. Given that May was still only 29 and threw left-handed, the Yankees felt he was a perfect fit for them and the dimensions of Yankee Stadium. Prior to May’s arrival, the Yankees did not have an effective southpaw in their rotation. That all changed with May’s arrival. He moved into the rotation and made 15 starts, won eight of 12 decisions, and logged an ERA of 2.28.

Given the chance to start the 1975 season in pinstripes, May took full advantage. Pitching a career-high 212 innings, he also picked up a personal best 14 wins. At one point that season, Yankee manager Bill Virdon placed May in high company, right alongside a onetime winner of the Cy Young Award.

“His stuff’s better than any left-hander I’ve seen,” Virdon told the Associated Press. “Vida Blue’s got a little better fastball, but I’d put [May] in Blue’s class.”

Thanks in large part to May, the improving Yankees finished a respectable third in the American League East.

In 1976, the Yankees thought highly enough of May to give him the first start at the newly remodeled Yankee Stadium. May would pitch decently in April and May, but it wasn’t enough to guarantee his long-term presence in pinstripes. At the trade deadline, the Yankees saw a chance to add two veteran starters to their rotation. They swung a blockbuster 10-man deal with Baltimore, sending May, two young lefties in Scott McGregor and Tippy Martinez, and catcher Rick Dempsey to the Orioles for a package that included Ken Holtzman and Doyle Alexander.

Trades are often difficult for players to accept, but the handling of the matter particularly upset May. According to May, he received news of the trade from another teammate, Jim “Catfish” Hunter, because Yankee manager Billy Martin did not want to tell him face to face.

Beyond the handling of the trade announcement, the Yankees would come to regret the substance of an infamous swap. Over the next season and a half, May would win 29 games for the O’s, where he blossomed under manager Earl Weaver. After the 1977 season, the Orioles used May’s renewed trade value to acquire platoon outfielder Gary Roenicke and relief ace Don Stanhouse in a trade with the Montreal Expos.

Ever the professional, the well-traveled May continued to do good work, this time in the National League. Over the next two years, the Expos used May as both a starter and reliever. He performed well in both roles, giving manager Dick Williams some valuable flexibility with his pitching staff.

By the end of the 1979 season, May was ready to leave Montreal and cash in on his free agent status. Regretting that they had ever traded him in the first place, the Yankees came calling with a three-year contract offer totaling $1 million. The Yankees used May in a kind of utility role, one that has become obsolete in the specialized game of today, splitting his time between the rotation and the bullpen. Responding beautifully, May won 15 games, an impressive total given that he started only 17 games all summer. Those 15 wins matched his career high. Even more decidedly, May posted an ERA of 2.46, the best of his career and a mark stellar enough to win the American League’s ERA title. May’s pitching became even more impressive in light of the elbow pain that plagued him for much of the summer. The switching between the bullpen and the rotation only taxed his arm further.

For the 35-year-old May, the 1980 season turned out to be a last hurrah. He struggled in 1981, so much that the Yankees traded him to Kansas City that winter in a one-for-one swap for DH Hal McRae. But the deal fell through when May, invoking his no-trade clause, vetoed the swap. May bounced back somewhat in ’82, but flatlined in ’83. Bothered by back trouble, May became so frustrated with his pitching that on a team flight, he flung his food tray in the air, nearly hitting Goose Gossage in the process. May and Goose exchanged words before Martin (of all people) intervened as the peacemaker. For a mild-mannered athlete like May, the display of anger was anything but typical.

In 1984, the Yankees brought him back for a Spring Training look, but May realized that he couldn’t pitch any longer; his bad back simply would not allow it. Now 39 years old, May understood that it was time to move on.

For about 10 years, May did little in retirement, until his daughters convinced him to return to the working world. So May took a job managing convenience stores and later became a managing consultant for British Petroleum. He finally retired in 2014 and spent most of his time fishing and doing yardwork.

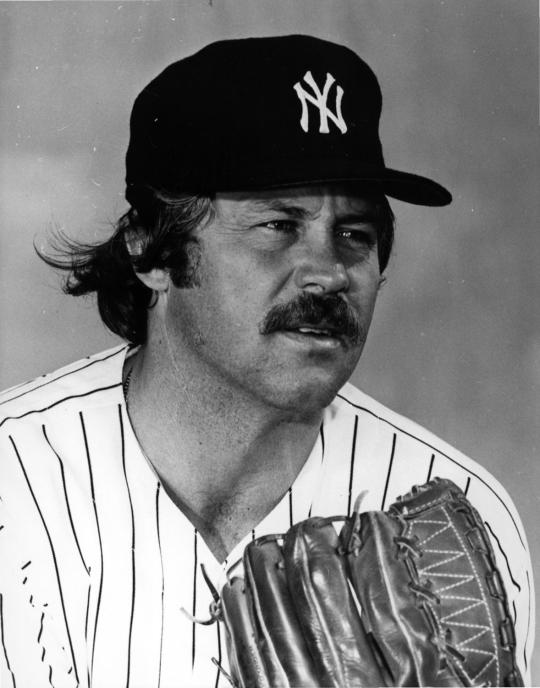

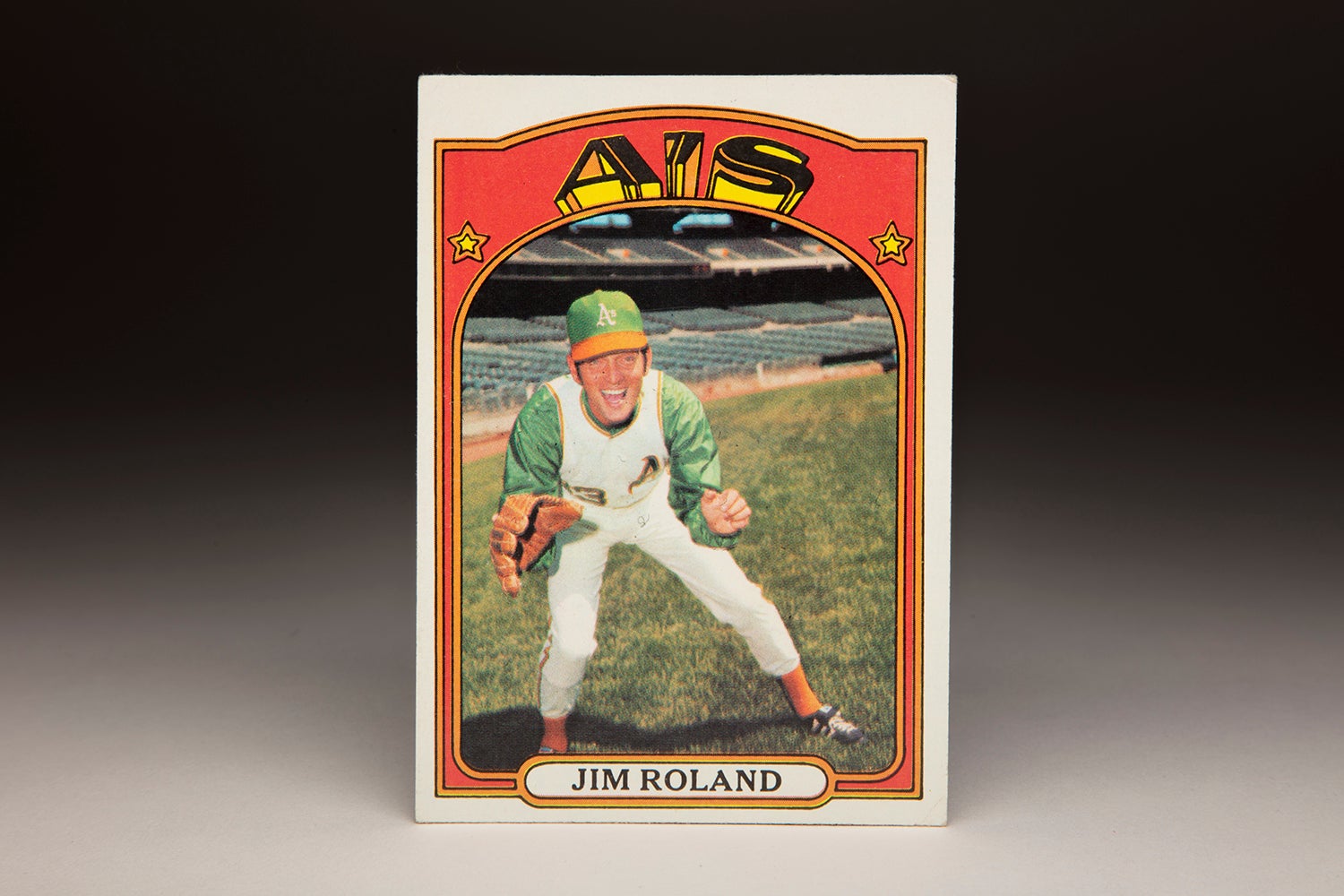

By the time Rudy May made his major league debut in 1965 with the California Angels, he had already been under contract to four organizations. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

When Rudy May was sent to the Baltimore Orioles as part of a 10-man deal, his Yankees teammate Catfish Hunter (pictured above) informed him of the news. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

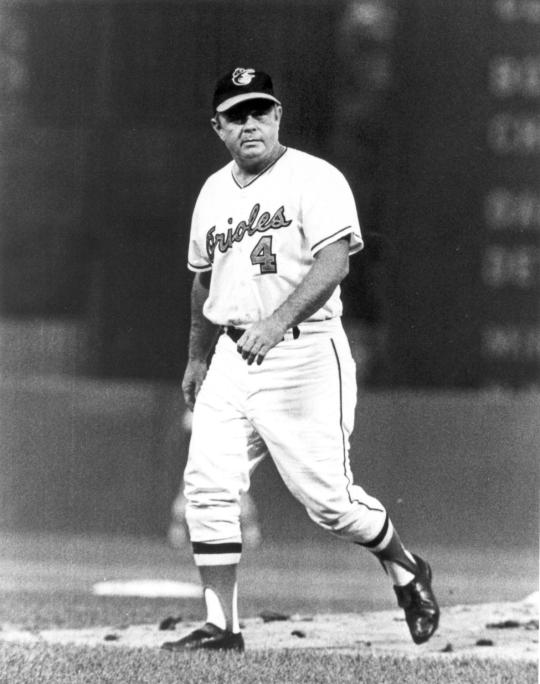

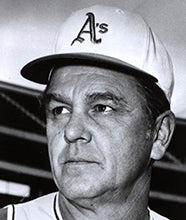

Rudy May blossomed under Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver (pictured above) during his stint with the Baltimore Orioles, winning 29 games after he was traded by the New York Yankees at the 1976 trade deadline. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

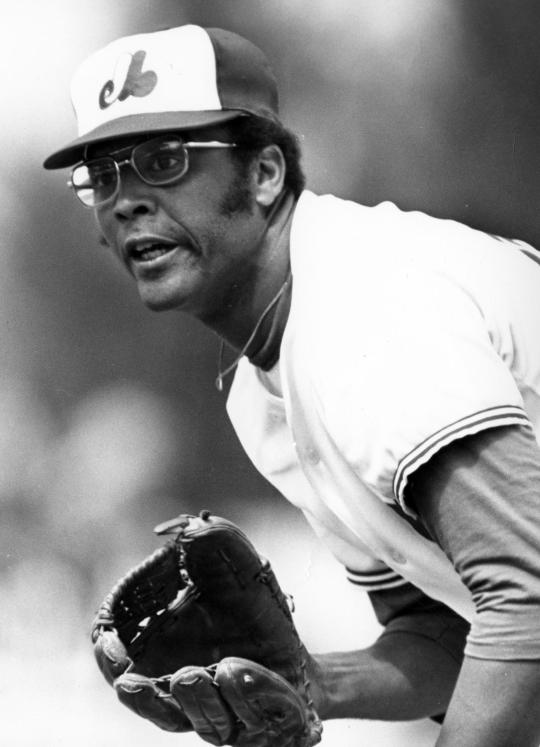

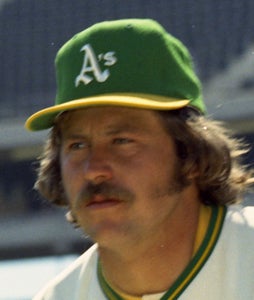

During his two-year stint with the Montreal Expos, Rudy May was used as both a starter and a reliever. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

May enjoyed a good life before passing away on Oct. 19, 2024, at the age of 80. But the road that he took to arrive there was anything but easy. From dealing with segregated clubhouses and anxiety on the pitching mound, to life with the “Hell’s Angels” and a succession of disruptive trades, May’s life in baseball was hardly as smooth as his picturesque pitching motion. A baseball life rarely is.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum