- Home

- Our Stories

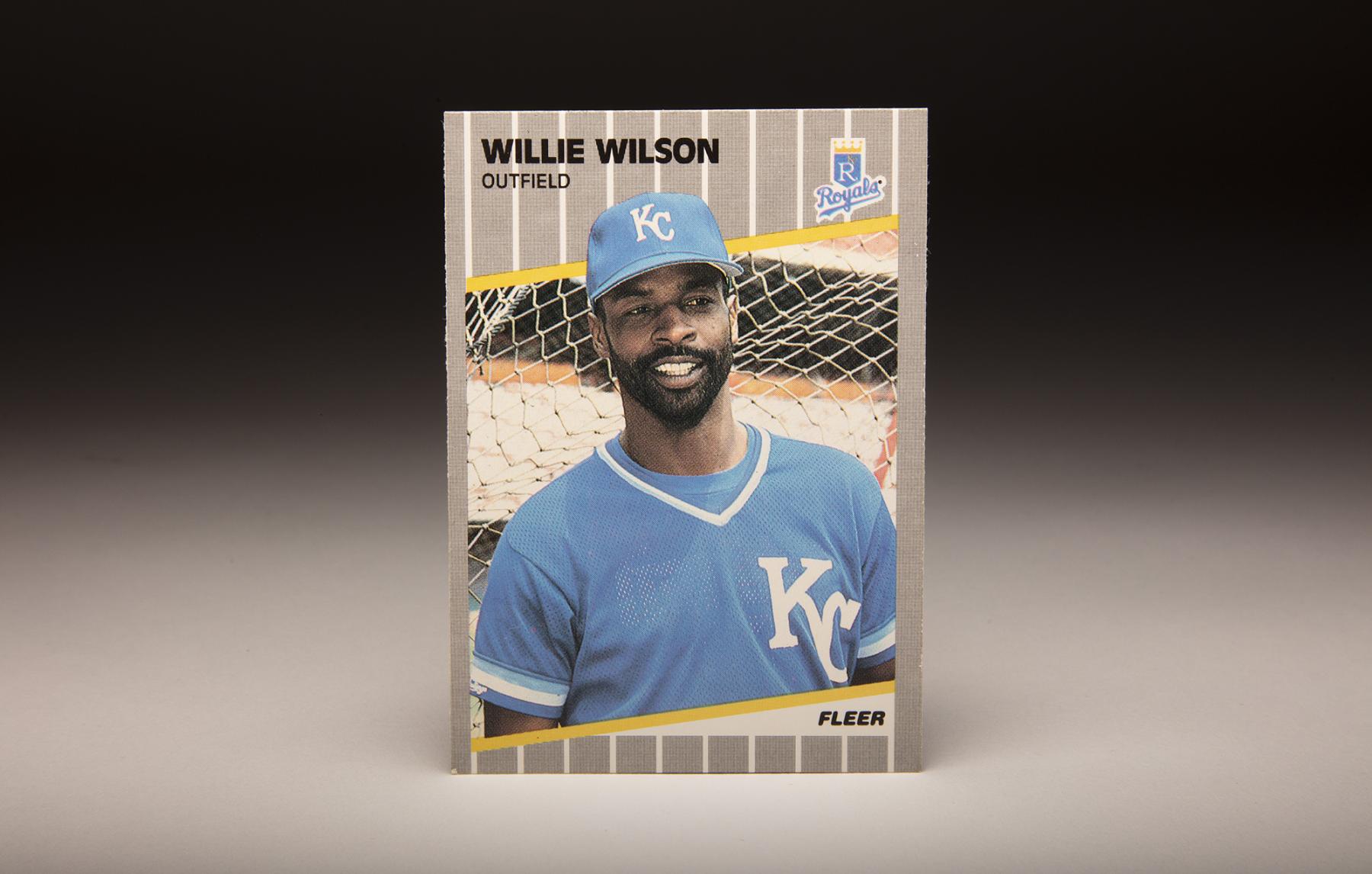

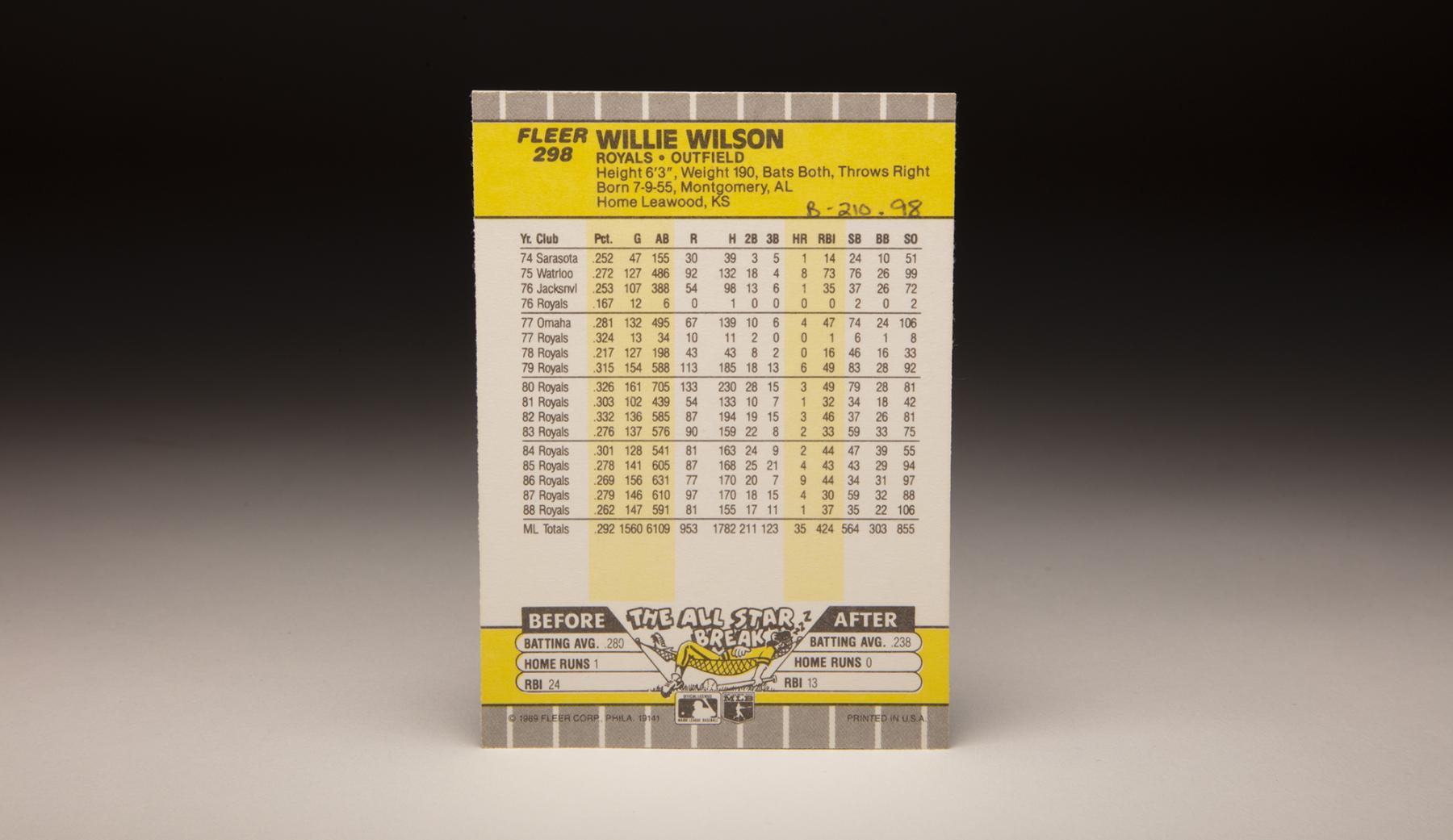

- #CardCorner: 1989 Fleer Willie Wilson

#CardCorner: 1989 Fleer Willie Wilson

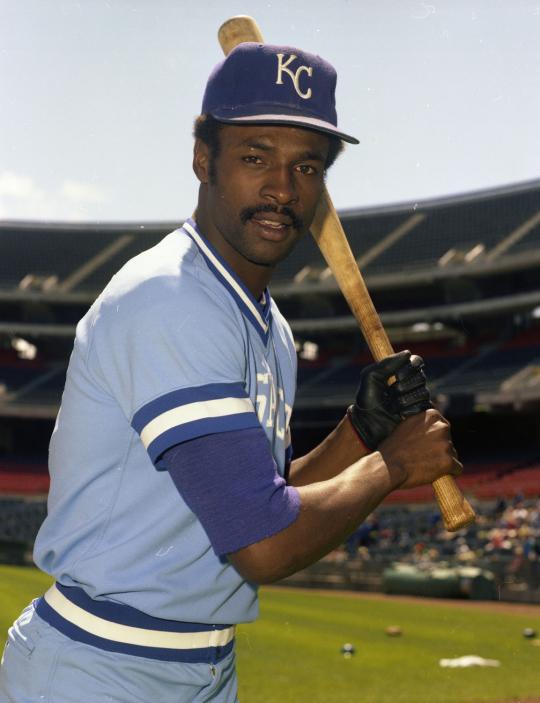

In 1979, Willie Wilson led the American League with 83 stolen bases in his first season as a regular in the Kansas City Royals’ lineup.

It would be the last time anyone not named Rickey Henderson would lead the AL in steals for seven seasons. But while the future Hall of Famer kept Wilson from re-writing the record books, Wilson still managed to compile a memorable career despite obstacles before and during his playing days.

Born Willie James Wilson on July 9, 1955, in Montgomery, Ala., Wilson was raised by his grandmother and other relatives as “Bobbie Lee” until the age of seven – when he moved to New Jersey to live with his mother, who called him by his birth name.

“I never met my real father,” Wilson wrote in “Inside the Park”, a 2013 book he penned with Kent Pulliam. “I don’t think my father ever knew that I played baseball.”

Wilson starred in youth football leagues but didn’t begin to play baseball until the summer following eighth grade. He wound up as a catcher but kept his focus on football and basketball, signing a letter of intent to play on the gridiron – after more than 200 schools recruited him – at the University of Maryland.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

A two-time high school All-American as a running back, the 6-foot-3 Wilson seemed destined to follow his heart into big-time college football. He told dozens of baseball scouts not to waste a draft pick on him, but the Royals – selecting 18th overall in the 1974 MLB Draft – rolled the dice and gambled that they could sign Wilson. A reported bonus of $85,000 to $90,000 – the most ever given by the Royals – changed Wilson’s mind.

“I got what I wanted,” Wilson told the Kansas City Times after signing. “I like football. But I figured in the long run baseball would help me out more. I figured I’d have a better career.”

The Royals sent Wilson to their Gulf Coast League affiliate in Sarasota, Fla., and told him to learn to play the outfield – where he had never played. After a slow start, Wilson wound up with a .252 batting average, 30 runs scored and 24 steals in 47 games.

Wilson’s contract called for an invitation to big league Spring Training with the Royals in 1975, and from there the team dispatched him to Waterloo of the Class A Midwest League. In 127 games, Wilson hit .272 with 73 RBI, 92 runs scored and 76 steals, setting a new Midwest League record for stolen bases and helping the Royals win the league title.

Royals farm director John Schuerholz ticketed Wilson for Double-A Jacksonville in 1976, and Wilson hit .253 with 37 steals in 107 games for the Suns – missing about a month with a pulled hamstring. When big league rosters expanded in September of 1976, Wilson got called up to the majors.

He appeared in 12 games and recorded his first big league hit – an infield single off Minnesota’s Jim Hughes – on Sept. 10. The Royals won their first AL West title that season, and Wilson – though far from a finished product – figured to be part of a bright future in Kansas City.

In the spring of 1977, the Royals informed Wilson that they wanted him to learn to switch hit. A natural right-handed batter, Wilson worked tirelessly with coach Chuck Hiller and focused on the left side of the plate when the Royals sent him to Triple-A Omaha to start the season. Wilson quickly adapted, hitting .281 with 74 steals in 132 games before again earning a late-season call-up to the big leagues.

This time, Wilson hit .324 and stole six bases. And though he once again was left off the Royals’ postseason roster, Wilson improved his skills that winter when he fell under the tutelage of Manny Mota while playing in the Dominican Republic.

“(Mota) really kind of taught me how to study pitchers,” Wilson wrote in his book. “A lot of people put in a lot of hard work and time with me. But it just seemed to click with him.”

Wilson reported to Spring Training in 1978 determined to make the big leagues. By his own estimate, he stole about 30 bases during games in Florida.

Royals manager Whitey Herzog – who told The New York Times that Wilson “was as fast as anybody I’ve ever seen” – made Wilson his Opening Day left fielder. He was hitting .291 through April but totaled only nine hits in May. Herzog transitioned Wilson to a bench role for most of the rest of the season – much to Wilson’s chagrin – and Wilson totaled just 198 at-bats in 127 games, hitting .217 while stealing 46 bases.

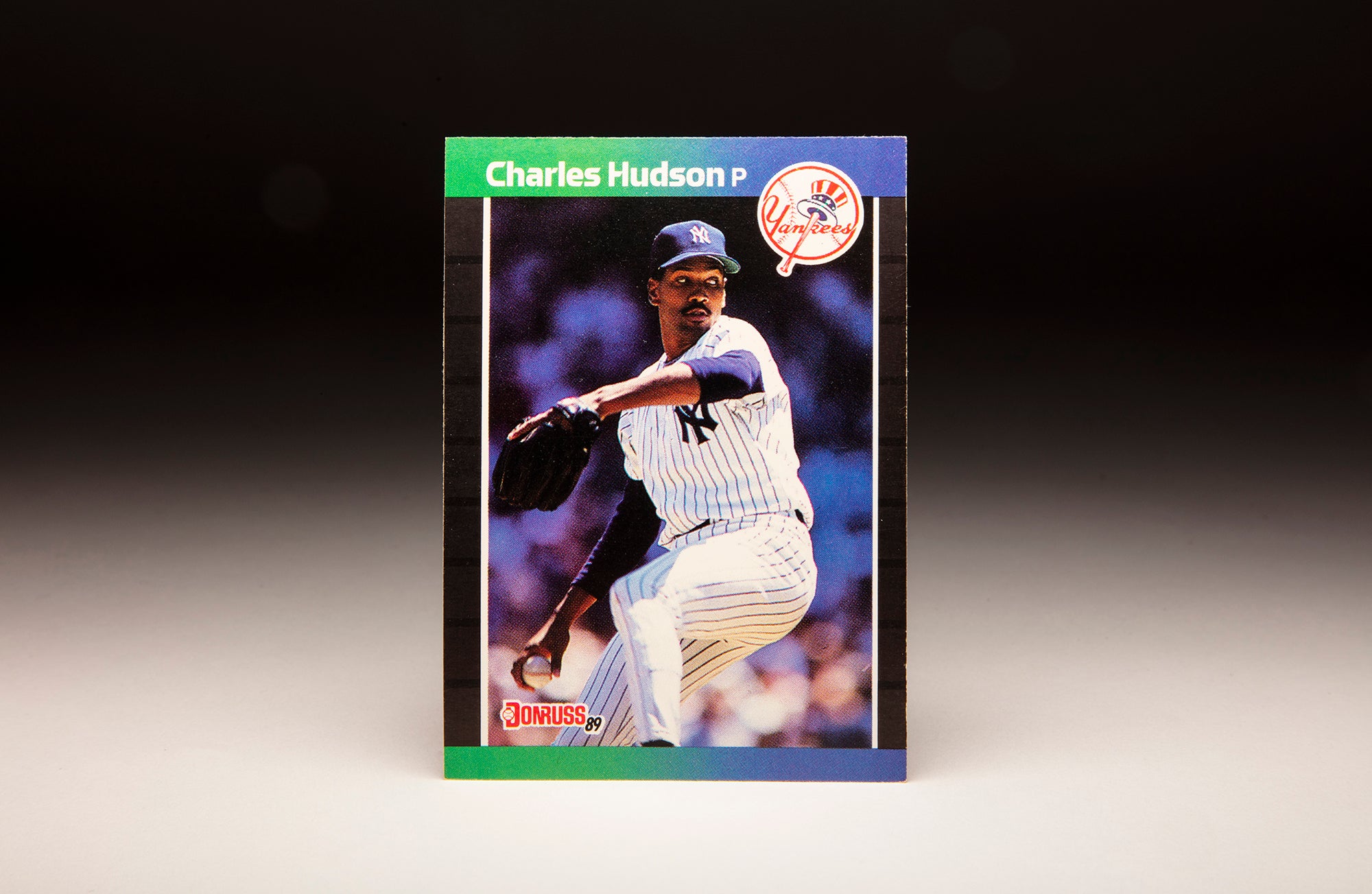

Wilson appeared in three games in the ALCS vs. the Yankees but came to the plate only four times as the Royals lost their third straight postseason series to the Yankees.

In 1979, Wilson began the season as a backup outfielder. But when starting right fielder Al Cowens was hit in the jaw by an Ed Farmer pitch in Texas on May 8, Herzog found himself short on outfielders.

Three days later, Wilson moved into the starting lineup. In 19 games through the end of May, Wilson hit .387 with 12 steals and 15 runs scored. He would remain a fixture in the Kansas City lineup for more than a decade.

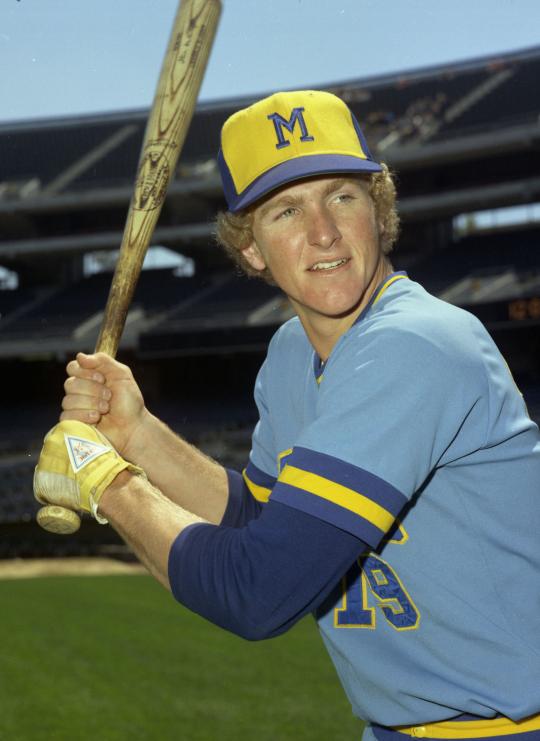

In 1979, Wilson hit five inside the park home runs – two coming in June alone. His only over-the-fence home run of the season came on June 15 against the Brewers, a three-run shot in the sixth inning that cleared the left field wall at County Stadium in Milwaukee. Three innings later, Wilson’s three-run, inside the park homer capped a seven-run, ninth-inning rally that powered Kansas City to a 14-11 victory.

“It just fell into place,” Wilson told the Kansas City Times. “When the pressure is on, our guys seem to come out of their shell.”

In 154 games in 1979, Wilson hit .315 with 113 runs scored and his 83 stolen bases – which was the top total in the big leagues.

He finished 17th in the American League Most Valuable Player voting, but the Royals finished out of first place for the first time since 1975 – and Herzog lost his job.

“So we were on a mission in 1980,” Wilson wrote, “to get to the World Series.”

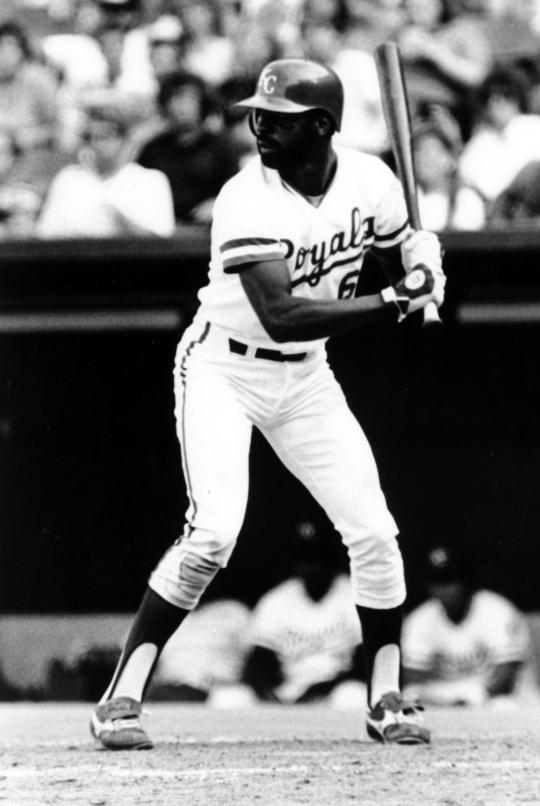

Wilson powered that mission with one of the best seasons ever by a leadoff hitter. He led the AL in runs (133), hits (230) and triples (15), becoming the first player in big league history to record at least 700 at-bats in one year and setting a since-broken record with 162 steals over consecutive seasons.

Wilson hit .326 and totaled 79 steals, earning a Silver Slugger Award and finishing fourth in the AL MVP vote. He also earned his first-and-only Gold Glove Award, a total seemingly low for a player whose defensive WAR was 1.9 or better each season from 1979-82.

Wilson hit .308 with four RBI as the Royals swept the Yankees in the ALCS, sending their bitter rivals home for the winter. But in the World Series, Wilson hit just .154 while striking out a record 12 times as Kansas City lost to Philadelphia in six games.

“I went out and tried too hard,” Wilson told United Press International after Game 6. “I went out and tried to do things I can’t do.

“If you want to say I lost it, say that. If it was because I didn’t get on base, say that.”

The memory of the World Series dogged Wilson in 1981, when he was hounded by fans throughout the season for his record-setting strikeout total. But he still hit .303 with 34 steals as Kansas City again advanced to the postseason before losing to Oakland in the ALDS.

In 13 plate appearances against the A’s in that series, Wilson hit .308 and did not strike out once.

“Everyone forgets I came to bat over 700 times (in 1980),” Wilson told The New York Times News Service. “I was dead tired. That could have accounted for my loopy swing in the Series. But no excuses. I just want to get back and try it again.”

In 1982, a hamstring injury limited Wilson to just two games in the first 26 played by the Royals. But he made up for lost time, overcoming a thigh injury and a beaning by Detroit’s Dan Petry with a remarkably consistent four-month run that saw him hitting .347 – best in the American League – when Sept. 1 dawned.

A September slump and a hot stretch run by the Brewers’ Robin Yount, however, whittled away Wilson’s lead in the batting title race down the stretch. With the Royals eliminated from the AL West race going into the season’s final day, Wilson’s average stood at .332. Yount’s was at .328 – with the Brewers facing the Orioles with the AL East title on the line.

The Royals chose to sit Wilson in the final game against the A’s, knowing Yount would have to go 4-for-5 to claim the title. But with three hits – a triple and two home runs – in his first four at-bats, Yount was poised to catch Wilson.

Both games headed into the ninth inning simultaneously, and the Royals prepared to have Wilson pinch hit if Yount recorded a hit in his final at-bat. But Yount was hit by a pitch thrown by Baltimore’s Dennis Martínez, ending the drama and keeping Wilson on the bench with a lead of .001 in the batting race.

Many media outlets around the country criticized Wilson for not playing.

“If I had known how much grief I was going to get about sitting out,” Wilson wrote, “I would have played and tried to get as many at-bats as (Yount).”

The injuries limited Wilson to 36 steals that season, but he still led all of baseball with 15 triples and earned his first All-Star Game selection and another Silver Slugger Award.

His toughest days, however, were yet to come.

“That winter, after I won the batting title, was when I first tried cocaine,” Wilson wrote in “Inside the Park”.

“It was wrong. I knew it was wrong. And even when I was doing it, I knew it was hurting me.”

That winter, Wilson was taped discussing cocaine on the telephone by authorities.

In 1983, Wilson – whose speed usually prevented long slumps – was hitting .278 on July 24 when he injured his left shoulder diving for a ball at Yankee Stadium in a game that would become famous for George Brett’s “pine tar” home run. The next day, while driving to the doctor’s office in Kansas City to have his shoulder examined – Wilson was pulled over by agents from the Kansas Bureau of Investigation and interrogated.

He would plead guilty – along with Royals teammates Jerry Martin and Willie Aikens – to attempting to buy cocaine. He was sentenced to serve three months of a one-year term in prison.

The Royals let Martin go as a free agent following the 1983 season and traded Aikens to the Blue Jays in exchange for Jorge Orta, who would play a crucial role for the 1985 World Series team.

Wilson, however, was brought back following his term in federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas. He was suspended from baseball for one year by commissioner Bowie Kuhn in December of 1983, but the suspension was commuted on May 16, 1984, and Wilson immediately returned to the Royals lineup after missing the team’s first 33 games.

In his first game back, Wilson went 1-for-3 with two walks as the Royals’ starting center fielder – a position that he inherited midway through the 1983 season when Kansas City finally nudged longtime star Amos Otis out of the job.

Wilson hit .301 in 128 games in 1984, stealing 47 bases and helping the Royals win another AL West title.

On April 10, 1985, Wilson – who was in the last year of a four-year deal – signed a “lifetime” contract with the Royals that guaranteed his contract through 1989 and had five option years. It was worth a reported $1.25 million per season.

Wilson, however, eventually negotiated a buyout that paid him a lump sum of about $5 million in the late 1980s.

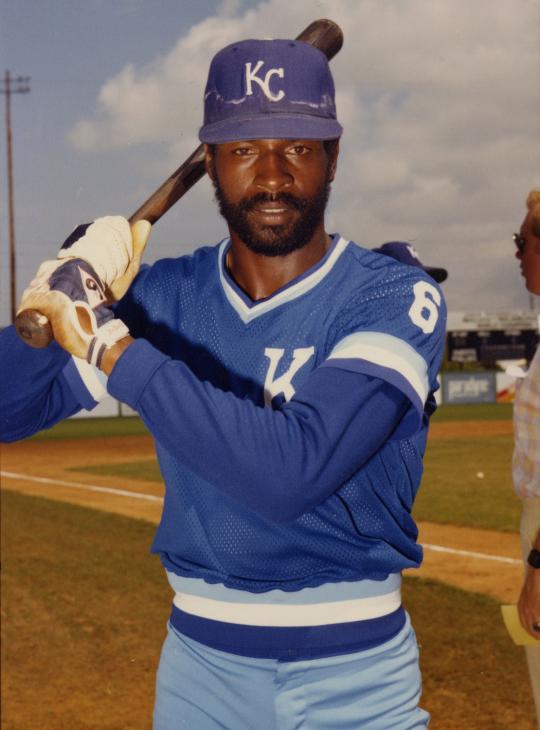

But after signing the new “lifetime” deal, Wilson and the Royals had a season for the ages. Wilson hit .278 with a MLB-best 21 triples and 87 runs scored, stealing 43 bases and helping Kansas City win the AL West again. Wilson’s RBI single in the bottom of the 10th against the A’s on the last day of the season gave Kansas City the division crown.

The Royals then rallied from a three-games-to-one deficit in the ALCS to beat Toronto, with Wilson hitting .310 with five runs scored. And in the World Series against the Whitey Herzog-led Cardinals, Wilson hit .367 with three steals and only four strikeouts as Kansas City again rallied from three-games-to-one to take the title.

The critical moment came in Game 6 when – with the Cardinals leading 1-0 and three outs away from the title – Orta led off the bottom of the ninth inning with an infield single on a play where he looked to be out but was called safe by umpire Don Denkinger. The Royals used the play as a springboard to rally for a 2-1 victory, then won Game 7 by a score of 11-0.

“Everybody felt like it was new life for us,” Wilson wrote. “You start thinking: ‘Is it our time now?’

“(Then) we win and it’s just the greatest feeling ever. I felt like I had redeemed myself.”

Wilson and the Royals endured a difficult 1986 season as manager Dick Howser fell ill. Wilson hit .269 with 34 steals, but bounced back in 1987 with 59 steals and an MLB-leading 15 triples. After the 1988 season where he hit .262 and once again led the AL in triples with 11, Wilson transitioned into a part-time player as the Royals infused their lineup with young talent like Danny Tartabull, Brian McRae, Kevin Seitzer and Bo Jackson.

“Bo was the biggest, strongest, fastest dude I had ever played with,” Wilson wrote. “You knew that if he ever learned to play the game the way you were supposed to do it, he would be a superstar.”

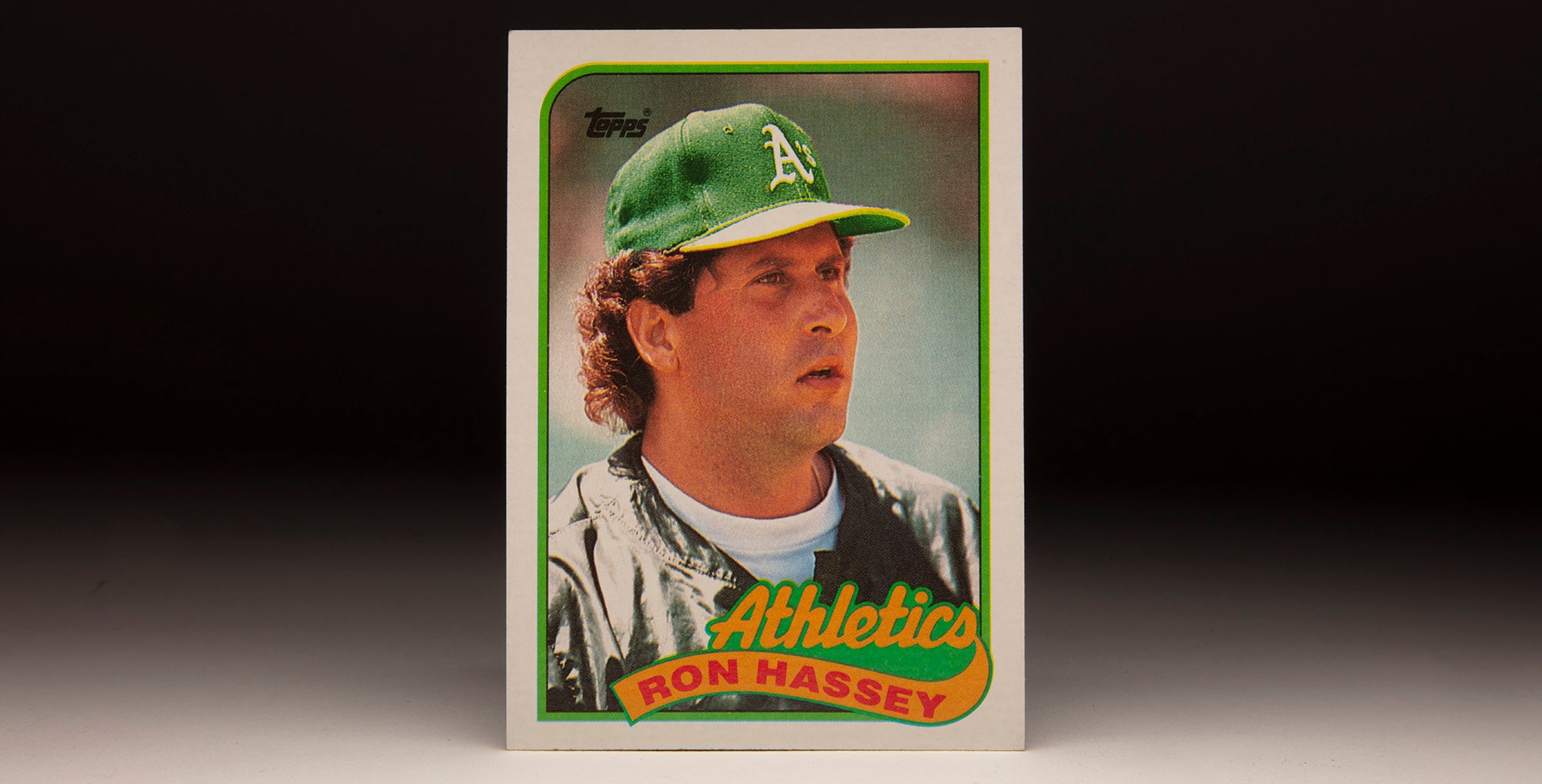

After hitting .290 with 24 steals in 115 games in 1990, Wilson’s option was not picked up and he left for Oakland as a free agent.

Wilson spent two years in Oakland as a veteran bat off the bench, stealing a combined 48 bases and helping the A’s win the AL West in 1992. It would be the final postseason of his career which – counting his first two seasons with the Royals when he was not on the playoff roster – featured eight division-winning teams in 19 years.

Wilson signed with the Cubs for the 1993 season and appeared in 105 games, hitting .258. On May 16, 1994, after playing in only 17 games that year – Wilson was released by the Cubs, ending his big league career.

After some investments went bad in the mid 1990s, Wilson returned to the game as a minor league coach with the Blue Jays in 1998. After a drug relapse the following year, Wilson got clean and was eventually elected to the Royals Hall of Fame in 2000.

He finished his career with 2,207 hits, a .285 batting average, 1,169 runs scored and 668 stolen bases. He ranks 12th on the all-time steals list.

“Speed makes the other team adjust to you,” Wilson said. “There’s no doubt about it: Speed irritates.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum