#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Kevin Maas

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Every once in a while, a rookie will receive a call-up from the minor leagues and embark on an historic tear that brings up comparisons to some of the game’s greats. That scenario has come up recently with the New York Yankees and their first-year catcher Gary Sanchez. After being called up by the Yankees in late July, Sanchez hit 11 home runs in his first 23 games. Teammate Mark Teixeira has already likened Sanchez to Babe Ruth, though he did so half-kiddingly. A few Yankee fans, with more reasonable expectations, have called Sanchez the franchise’s best young homegrown catcher since Thurman Munson.

In 1990, the Yankees experienced a whirlwind debut from another first-year player, albeit one not as highly touted as Sanchez. That was the summer that the Yankees summoned Kevin Maas from the minor leagues. The 1990 Yankees needed help in the worst way. They were on their way to a 67-win season and a last-place finish in the American League East. They had the worst offense in the league, and their best hitter was Jesse Barfield, a good player who was by then past his prime. Their best starting pitcher was Tim Leary - the right-hander, not the American psychologist - who was on his way to a 19-loss season. It was almost certainly the worst team the Yankees had fielded since the hazardous days of 1966 and ‘67.

In the midst of a baseball shipwreck, Yankee fans found some hope at the end of June, when general manager Harding “Pete” Peterson called up Maas from Triple-A Columbus. At the time, most Yankee fans knew little about Maas. He was a prospect, but not a particularly heralded one - certainly not a blue chip, can’t-miss type phenom.

Expectations weren’t high, but Maas soon caught the fans’ attention. Almost from the start, he showed himself to be a cut above the other young players, like Jim Leyritz and Oscar Azocar, who also joined the Yankees that summer. The Yankees tried to hype Azocar and Leyritz as linchpins of a new youth movement, but in reality they were limited players. Azocar was at best a fourth outfielder, albeit one with a great attitude, while Leyritz would become a good bench player (and an important part of the 1996 world championship team) but hardly the building block on which to base a complete reconstruction.

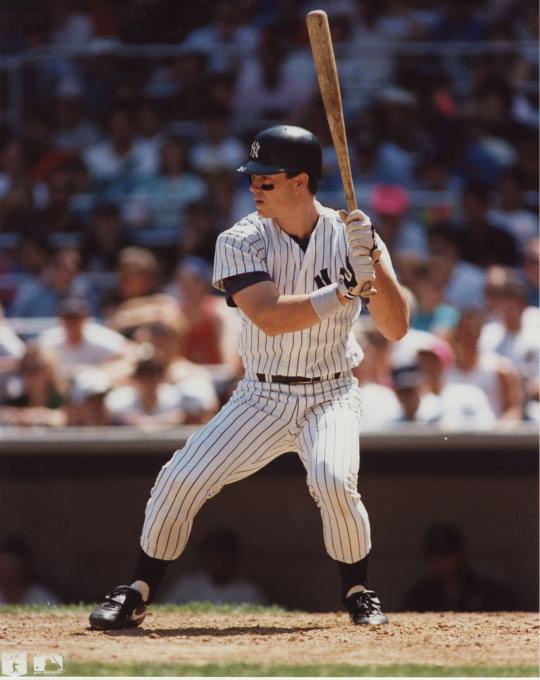

Without question, Maas looked like the best of the three young players. Although he had little defensive value as a lumbering first baseman, it was plainly obvious that he could hit. Unlike Leyritz and Azocar, Maas possessed a keen batting eye; he rarely ventured out of the strike zone to swing at bad pitches. He also possessed a picturesque swing, which seemed to be cut out of the pages of a hitter’s manual. With a natural uppercut and an ability to pull the ball to right field, the lefty-swinging Maas looked like a gift from the baseball gods to a struggling franchise that had hit rock-bottom.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Maas did his best to pry the Yankees out of last place. From the get-go, the 25-year-old slugger hit ferociously. In 254 at-bats as a rookie, he blasted 21 home runs, slugged .535, and put up an on-base percentage of .367. His batting average was not that impressive, at .252, but his ability to draw walks raised his on-base numbers to a very satisfactory level. Maas finished second in the American League Rookie of the Year balloting, behind only Cleveland's Sandy Alomar, Jr.

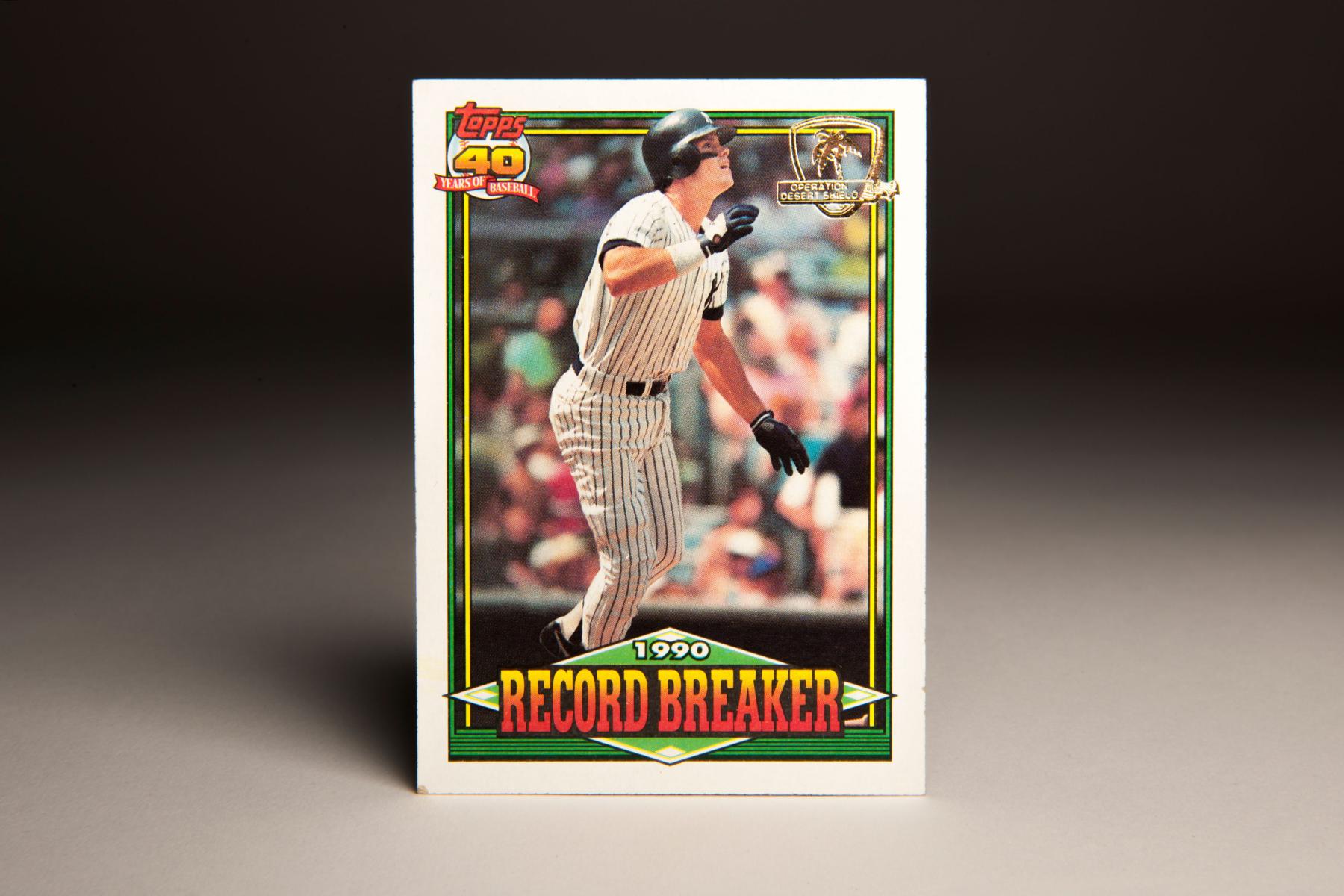

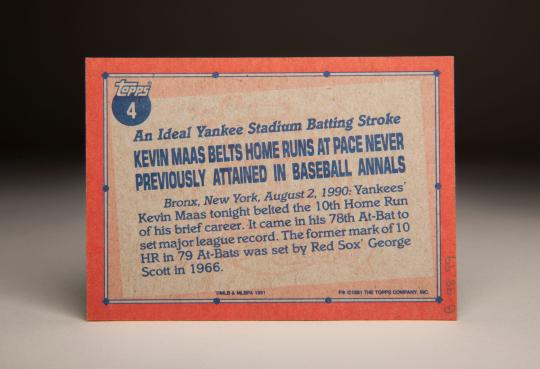

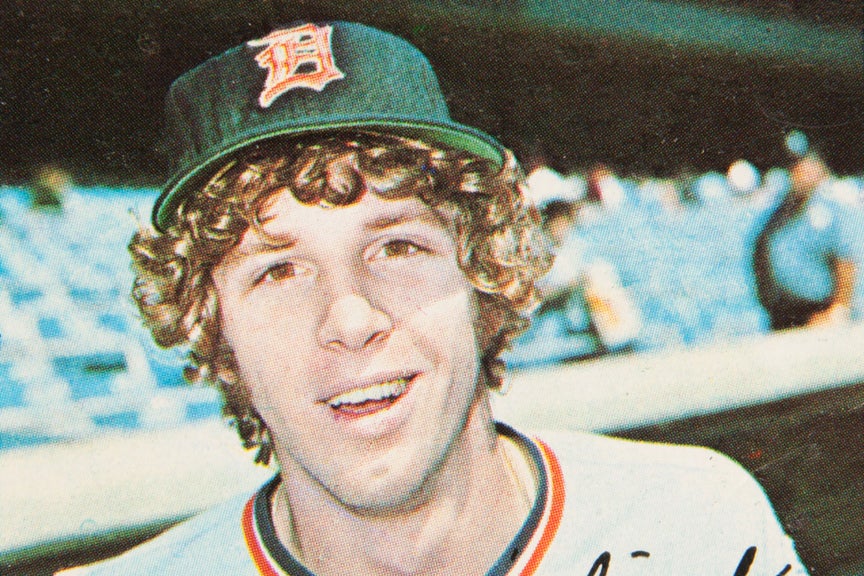

Maas’ mid-season surge earned him a place in Topps’ 1990 update set. And then in 1991, Topps came out with Maas’ first regular issue card, along with this “Record Breaker” card, seen here. In hitting 10 home runs over his first 77 at-bats, Maas established a rookie “record,” since broken by Shane Spencer in 1998 and Sanchez in 2016. On this card, the chiseled Maas looks like the prototypical ballplayer, with a muscular but lean upper body, a lantern jaw, and a picturesque follow-through to his swing. Having just dropped his bat to the ground, Maas is looking toward the outfield. Based on the angle, it appears that he might be following the flight of one of his 21 first-year home runs. Whether a home run or not, it’s a beautiful, well-photographed card, part of an excellent set that Topps featured in the spring and summer of ’91.

It’s no surprise that Maas, a good looking ballplayer, quickly became a heartthrob at Yankee Stadium, prompting lookalike comparisons to actor Rob Lowe. (At the time, Lowe was starring in the film Bad Influence.)

Based on what he did in 1990, no one could have known that Kevin Maas’ baseball cards would become nothing more than common pieces of cardboard. This 1991 card, while still visually striking all these years later, has no special value, simply because Maas did not carry through the initial hype.

Maas never made it back to the majors. So what happened? How could a player who took the country by storm as a rookie be out of the big leagues within five years, done at the age of 30 and eventually forced to seek employment in the Japanese Leagues? One theory maintains that Maas was simply not that good. He was never rated a top prospect by Baseball America, never considered a phenom, certainly not the way that Sanchez has been throughout his professional career.

Still, I think there is more to it than that. Injuries also played a part in Maas’ decline, rendering him an old 30. Beyond that, Maas struggled to adjust. He always had a beautiful swing and a disciplined batting eye, but he also had rather stiff movements within the batter’s box, to the point where he looked almost robotic. He had trouble with breaking pitches and never really improved in that area. Overall, Maas failed to advance his game, unable to make adjustments once pitchers had figured out some of his weaknesses.

After Maas retired, I heard something that might have also helped explain his fast decline. Some friends of mine told me that they once met Maas at the Yankees’ “Fanfest” event in New York City. Of all the players they met, Maas was the most unpleasant. Coming across as arrogant, he spent most of the time complaining about how tired he was after a night out on the town. After hearing about this, I began to wonder if Maas’ attitude explained his inability to sustain a good major league career. Was he simply too egotistic to try to improve his game? There was no way to know for sure, but the story of Maas at Fanfest made me think.

In 2009, I heard that Maas would be visiting Cooperstown to take part in the inaugural Hall of Fame Classic Weekend. Maas was supposed to serve as an instructor at the youth baseball clinic scheduled for Friday afternoon. I brought my nephew to the clinic unsure of what to expect. We took our seats in the covered grandstand at Doubleday Field, where the clinic took place because of a heavy rainstorm that afternoon.

I was amazed by Maas’ impressive effort during the clinic. He was one of the stars of the show; he was well-spoken, demonstrative, and charismatic. In spite of the pounding rain in Cooperstown, he acted as if there were no other place he would rather be than Doubleday Field. I came away from the clinic contemplating two possibilities: Either my friends had simply caught Maas on a bad day, or he had grown up and matured significantly since that day at Yankee Fanfest. I’d prefer to think it’s the latter.

In terms of his decline as a player, I’m still not sure what happened to Kevin Maas, how he went from rookie sensation to major league outcast within the span of five seasons. Frankly, I’m not sure that I care anymore about that; all that matters is the way that Maas worked with those kids here in Cooperstown back in 2009.

I now think good thoughts when I think of Kevin Maas. That rainy day at Doubleday Field made sure of that.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame