- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1991 Topps Dwight Evans

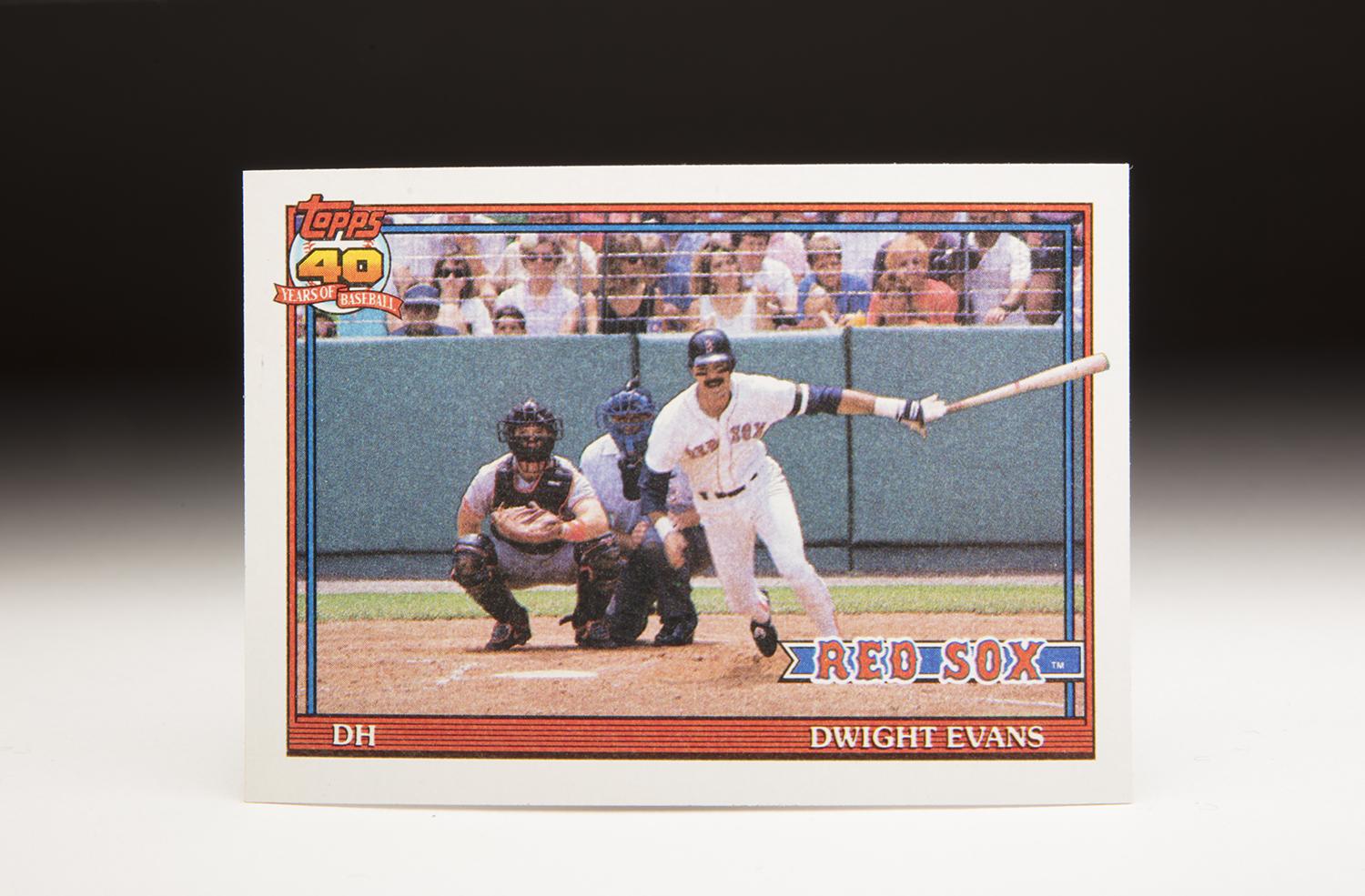

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Dwight Evans

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

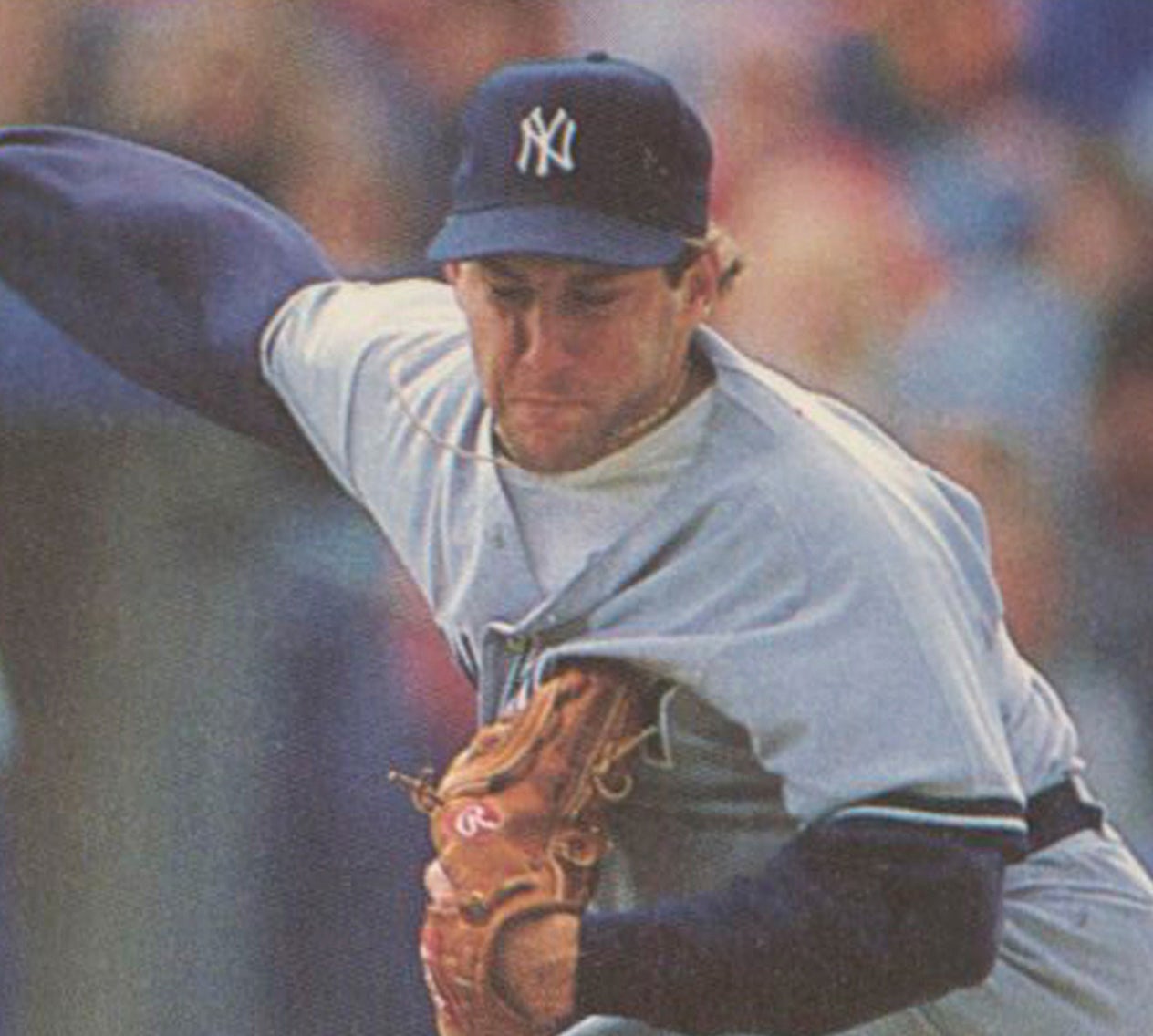

When we see a card depicting a batter in action, the photographer almost always gives us a view from the dugout opposing the batter’s box. So for a left-handed hitter, the viewpoint usually comes from the dugout on the third base side of the playing field. For a right-handed hitter, the shot comes from the first base dugout, or some point near it. Every once in a while, a photographer might take a photo from the same side dugout, in which case we would see the back of the hitter.

Yet it is very rare to see a hitter from the straight-on perspective of center field. That is what is so striking about Dwight Evans’ 1991 Topps card. Taken from somewhere in the center field bleachers at Fenway Park, or perhaps from one of the bullpens, the photo gives us a head-on look at Evans as he completes his swing in a game during the 1990 season. As a result, we see the juxtaposition of Evans, the catcher, and the home plate umpire, all sandwiched together in close confines. It’s a view that we’re used to watching on television at home, but an unusual layout for a baseball card.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

To make the card even more intriguing, we see that Evans has finished his swing, having released his bottom hand and extended his bat far to the left so that it is pointing toward the third base dugout. This is exactly the way that Evans was taught how to hit by Walt Hriniak, the man who helped him transform from an average hitter into a productive one. At the point that the picture has been snapped, Evans’ body has completely opened up, so that he is directly facing the pitcher and looking straight in the direction of the ball, which appears headed somewhere toward the center of the field.

The card also features a bit of incongruity. We remember Evans best for his standout defensive play in right field, but his card lists him as a DH, or designated hitter. The DH listing is a sign of the inevitable aging of a ballplayer. Evans is nearing the end of his career. In fact, this Topps card would be the last to show Evans as a member of the Boston Red Sox, in what turned out to be his final season in the major leagues.

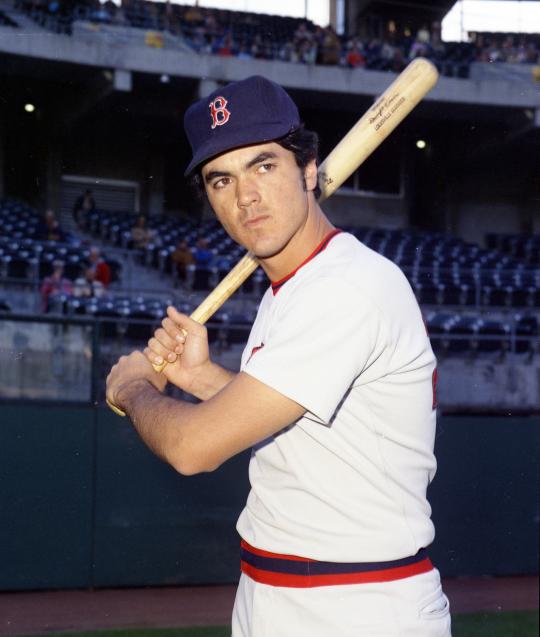

Unlike many players, Evans didn’t appear to age much physically during his long career. Even at the end, he remained lean and well-conditioned. His face retained a youthful glow, thanks in part to his ever-present mustache and his dark features. But the Evans of 1991 was a much different player than the Evans of 1972, when he made his big league debut. The younger Evans was no DH – the rule did not even exist at that point – but was instead a lithe, athletic outfielder who could pin down baserunners with one of the strongest and most accurate throwing arms of any era.

The Red Sox made Evans their fifth-round draft choice in 1969, sending him to Jamestown of the NY-Penn League, where he hit a respectable .280, albeit with only one home run. He would move up quickly. The power started to come for Evans at Greenville of the Western Carolinas League in 1970. By 1971, he reached double figures in home runs at Single-A Winston-Salem. (That was also where he acquired the nickname “Dewey” from manager Don Lock, who had already dubbed two other players “Newie” and “Lewie.”) And by 1972, Evans became a dominant force at Triple-A Louisville, hitting an even .300 with 17 home runs and 90 walks.

Liking what they saw, the Red Sox promoted the 20-year-old Evans to Boston in September. Playing both left field and right field, Evan played in 18 games and more than held his own against American League pitching. Based on his late-season performance, not to mention his big numbers at Triple-A, the Red Sox had every reason to believe that Evans would become their everyday right fielder in 1973.

After the 1972 season, Evans suffered a setback when he played in the Venezuelan Winter League, only to quit in midseason. Evans’ problems involved a dispute with his manager, Luis Aparicio, who also happened to play shortstop for the Red Sox. To his credit, Evans took the blame for the incident. “What happened down there between Luis and me was probably all my fault,” Evans told sportswriter Bill Liston. “It really was not as much of a flap as some people heard it was.”

Evans’ disagreement with Aparicio typified some of the behavior of his early career. He had a tendency to be moody, and sometimes snapped at teammates and reporters. That would eventually change. In time, Evans would mature, becoming one of the most even-tempered members of the Red Sox.

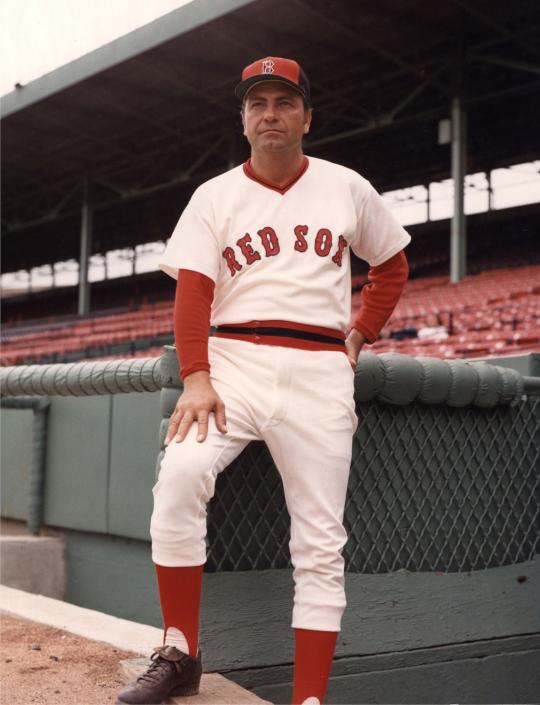

As a rookie in 1973, Evans played both left and right field, excelling defensively. He also contributed 10 home runs, but his .223 batting average spoke volumes about his inconsistency as a hitter while also limiting his playing time. In 1974, Evans made significant strides, Evans raising his batting average to .281 and displaying the kind of throwing arm that reminded scouts of another young player, Pittsburgh’s Dave Parker, along with the late Roberto Clemente. Evans’ play certainly drew an endorsement from his manager, Darrell Johnson.

“Dwight Evans is the best right fielder in the American League,” Johnson said without hesitation in an interview with the Boston Herald.

In 1975, Evans helped form one of the best outfielders in the major leagues. Joined by rookies Jim Rice and Fred Lynn, Evans once again stood out on defense, while hitting 13 home runs and raising his OPS over .800. Evans played even better in the World Series, when he batted .292 against the Cincinnati Reds. In Game 3, Evans hit a dramatic game-tying home run in the ninth inning, but then saved his most remarkable moment for Game 6. That’s when he hauled in Joe Morgan’s long drive in the 11th inning, preventing what could have been a game-breaking home run, and then doubled off Ken Griffey with one of his patented rifle throws to first base. In an interview with the Sporting News, Reds manager Sparky Anderson called it “the best catch I’ve seen. We’ll never see any one better.”

After the heights of 1975, Evan encountered struggles the next two seasons. He slumped to a .242 batting average in 1976, though he did win the first of his eight career Gold Gloves, and then missed nearly 100 games in 1977 with a nagging knee injury.

In 1978, Evans showed up to Red Sox camp a changed man. Abandoning the moodiness of his early years, Evans decided to take matters stride and have fun. “The best thing I’ve done this year is relax,” Evans told Alan Richman of the Boston Globe. “I’ve decided that if I’m going to be a lousy ballplayer, I might as well relax and give it my best.”

Evans was anything but lousy in 1978. He played well through August, at least until the date of Aug. 28. That’s when he was hit in the head by a pitch from Seattle’s Mike Parrott. The beaning was horrific, the kind of injury that would have mandated extensive tests for concussions in today’s era. But Evans returned from the beaning only five days later. Feeling dizzy for the balance of the season, Evans struggled at the plate and batted under .150 the rest of the way. As a result, Evans did not start the final game of the Red Sox’ season – the famed tiebreaker against Ron Guidry and the New York Yankees.

Feeling better in 1979 and ’80, Evans put up two more typically solid seasons for the Red Sox. He remained an excellent defender and a competent hitter, but something short of a star. That would all begin to change during the strike-shortened season of 1981.

The 1981 season brought in a new Red Sox regime, headed up by manager Ralph Houk. The former skipper of the Yankees and Detroit Tigers made an immediate alteration with Evans, who had normally batted in the lower-third of the Red Sox’ order. Recognizing Evans’ patient approach to hitting and his ability to reach base, Houk made him his everyday No. 2 hitter. Not only did Evans assemble his best season offensively, but he emerged as the Red Sox’s best player, while leading the league in home runs, walks, total bases and OPS.

Houk’s decision had an impact, but so too did the influence of Walt Hriniak. Although Hriniak was officially listed as the Red Sox’ bullpen coach, he actually put in time with many of the Red Sox’ hitters, including Evans. Hriniak changed Evans’ batting stance, encouraging Evans to hold his bat flat, instead of straight up and down, and urging him to hit the ball up the middle. Like many Hriniak disciples, Evans would release his top hand from the bat after contact.

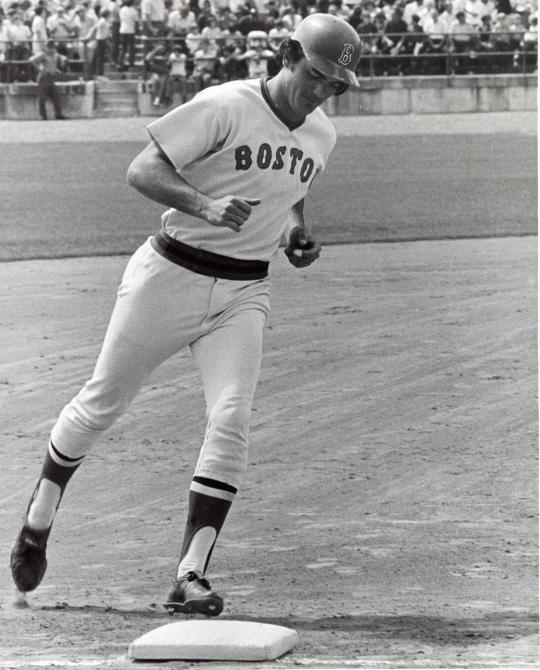

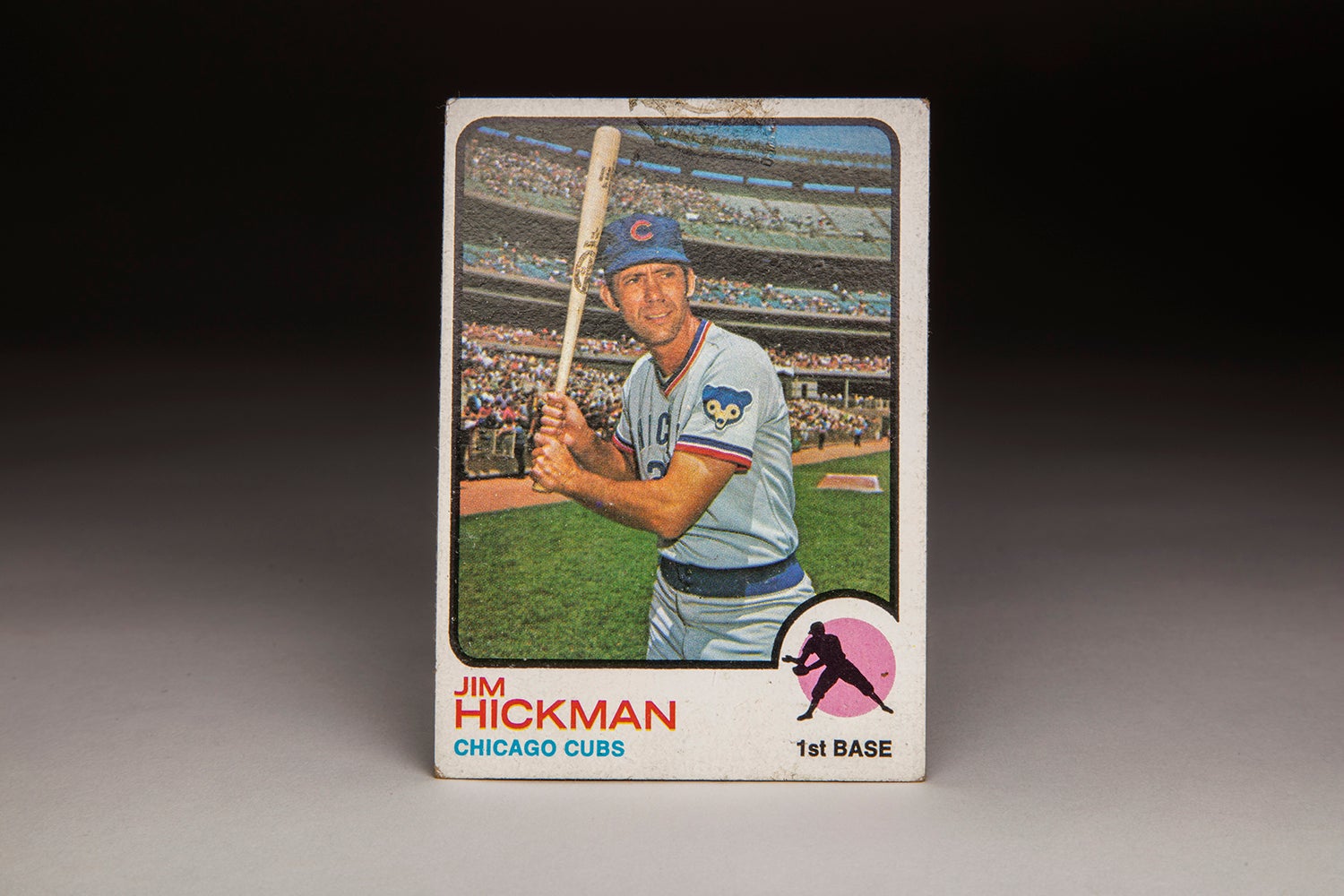

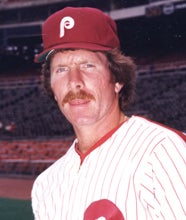

Dwight Evans played for the Boston Red Sox from 1972 to 1990, one year before his final full season in 1991. (Doug McWilliams/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

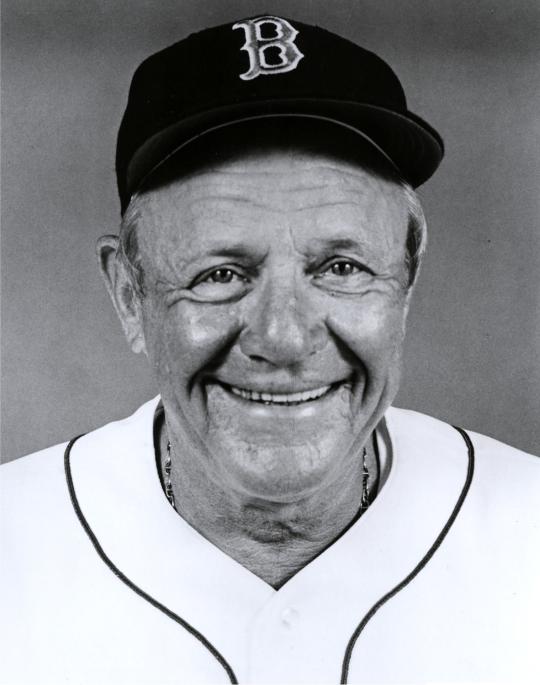

Red Sox manager Darrell Johnson gave rookie outfielder Dwight Evans a ringing endorsement in 1974, proclaiming him "the best right fielder in the American League." (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

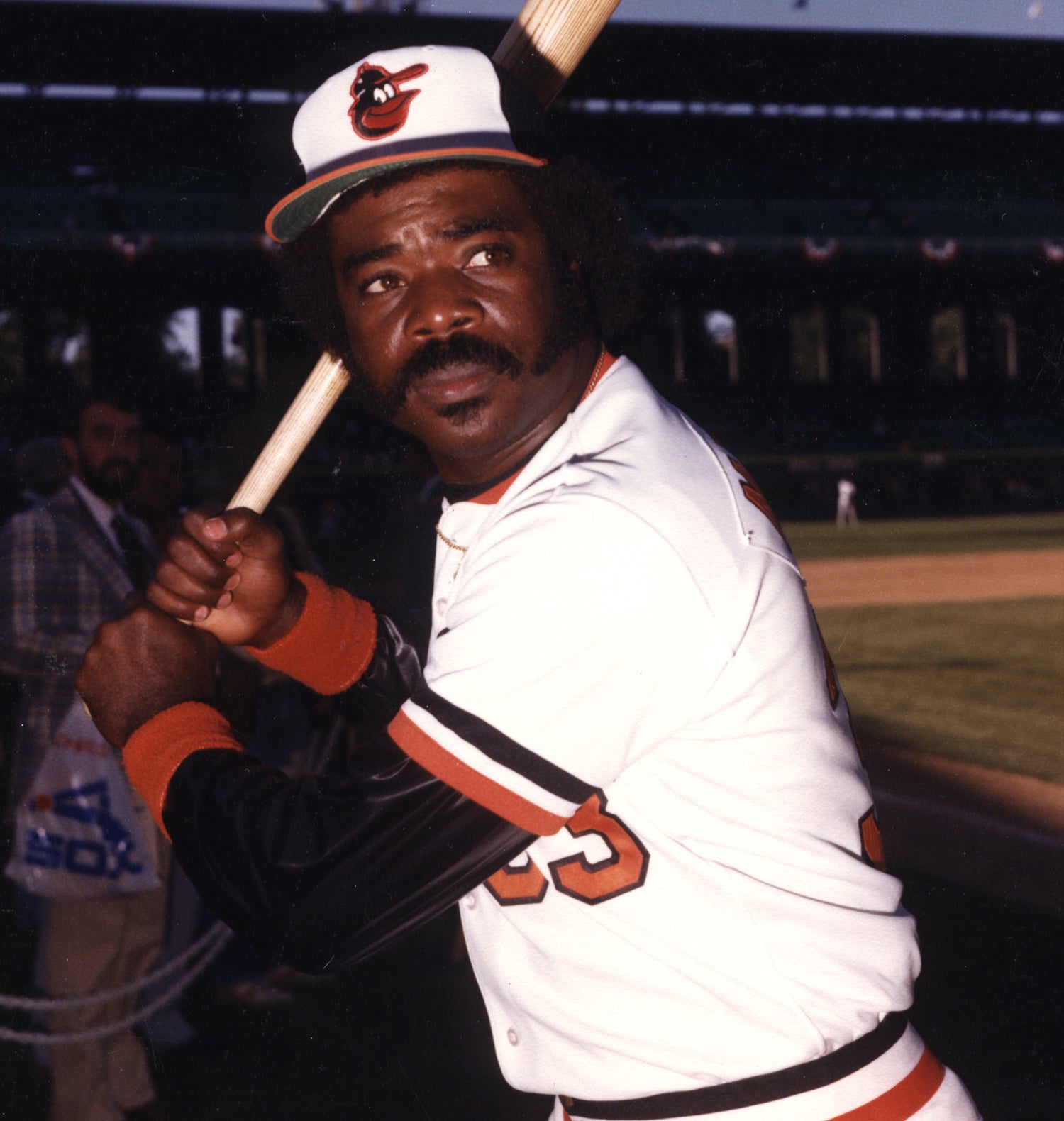

By the time the 1980s ended, Dwight Evans had hit more home runs in the decade than any other player, with 256. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Starting to show positive results with the new approach in the middle of 1980, Evans burst through completely in 1981. Given a full, strike-free season in 1982, Evans continued the onslaught. He led the American League with a .402 on-base percentage, while hitting .292 with 32 home runs. No longer a player who led with his glove, Evans had become a legitimate two-way star for the Red Sox.

Evans remained a force for the Red Sox for the rest of the decade. He continued to make adjustments along the way, such as becoming John McNamara’s leadoff man in 1985. Despite a lack of standout speed, Evans filled the role capably, in large part because he walked 114 times. In 1986, McNamara moved Evans to the sixth spot in the lineup, but Evans didn’t seem to mind, increasing his OPS to .853 in helping the Red Sox win the pennant for the first time in more than a decade.

As he did in 1975, Evans excelled on the World Series stage. Against the vaunted pitching staff of the New York Mets, Evans hit two home runs and posted an OPS of 1.015. For his 14 career World Series games, Evans batted an even .300 with three home runs and 14 RBI.

Although the Red Sox fell of their game in 1987, Evans did not. Leading the league with 106 walks, Evans topped .300 and accrued 34 home runs while making a smooth transition to first base. He played so well that the American League beat writers placed him fourth in the league’s MVP voting. He continued to hit well in 1988 and ’89, even as he began to spend more and more time in the DH role. By the time the decade ended, Evans had hit more home runs in the 1980s than any other player, an impressive feat given the presence of such stars as Mike Schmidt, Eddie Murray and Andre Dawson.

It was not until 1990 that Evans started to show any significant decline in his game. That was largely attributable to back problems, which curtailed his playing time that summer. Concerned that his back issues would prevent him from playing much, the Red Sox released him after the season.

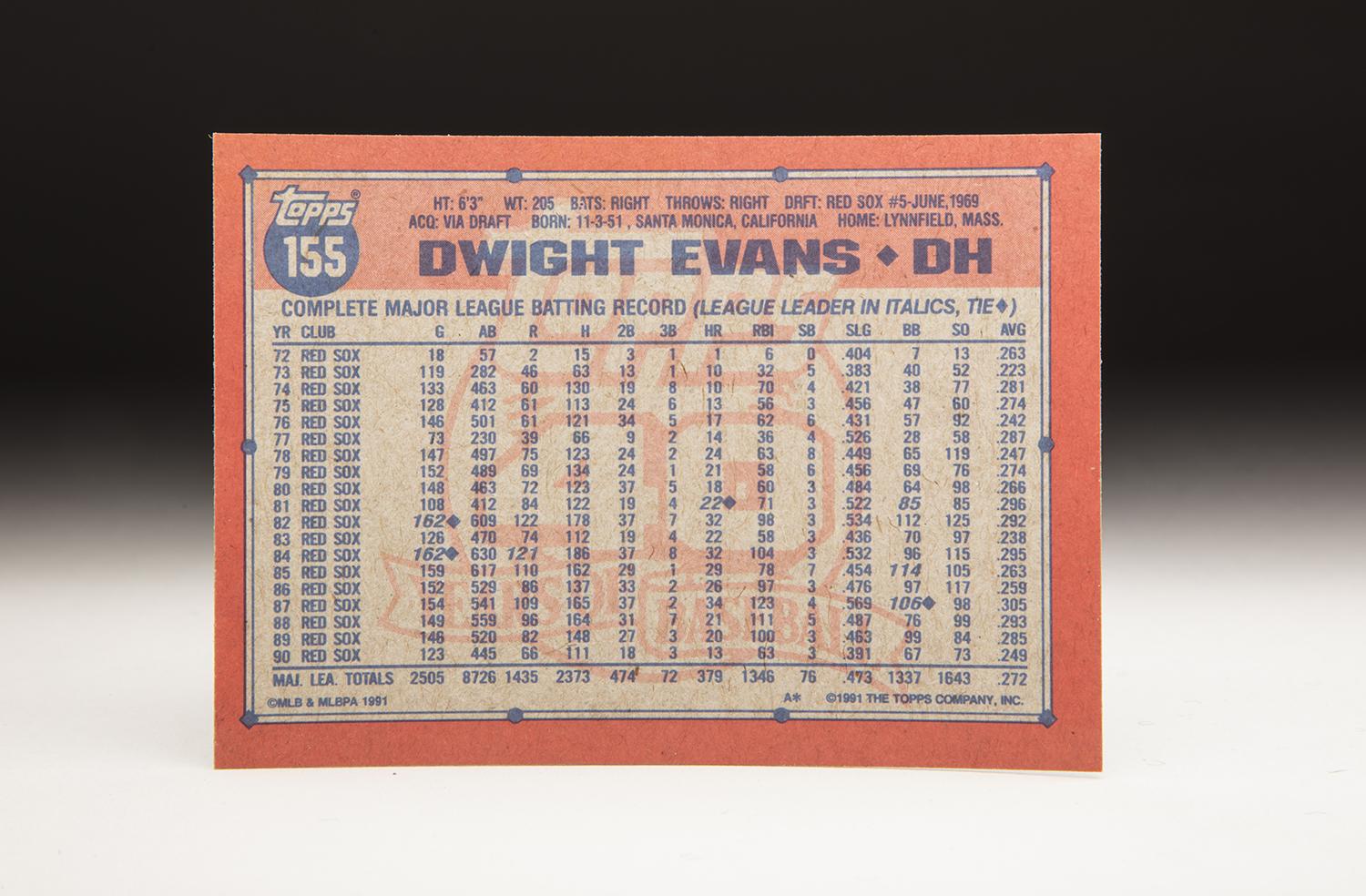

By the time that Evans had been released, Topps had already committed to making a 1991 card showing him with the Red Sox. But after the Baltimore Orioles picked up Evans, Topps corrected the situation by issuing a Topps Traded card for him later in the season. That explains why Evans appears on two Topps cards in the 1991 set.

In spite of his back problems, Evans posted decent numbers for the Orioles as a DH in 1991. The O’s brought him back for Spring Training in 1992, but released him near the end of camp, ending his career after 20 seasons.

Since the end of his playing days, Evans has worked periodically as a coach for major league teams, including the Red Sox, Chicago White Sox and Colorado Rockies. He and his wife, Susan, have also gained admiration for the care of their two sons, both of whom suffer from a disease known as neurofibromatosis. The disease, which is sometimes called elephant man’s disease (and was made well known by 19th century Englishman John Merrick), is a genetic disorder that can cause disfigurement. Quietly behind the scenes, Evans has worked hard to raise money for research into the disease and ways to improve its treatment.

Evans’ patience in dealing with the effects of neurofibromatosis has typified his growing maturity over the years. At one time, he periodically lost his temper because of his sons’ struggles, but now he simply looks to assist the situation as best as he can. In a similar way, he showed growth as a player; not satisfied with merely being competent, he worked hard to become a star.

That seems to be the theme of Dwight Evans life: Finding a way to get better.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame