- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1993 Topps Candy Maldonado

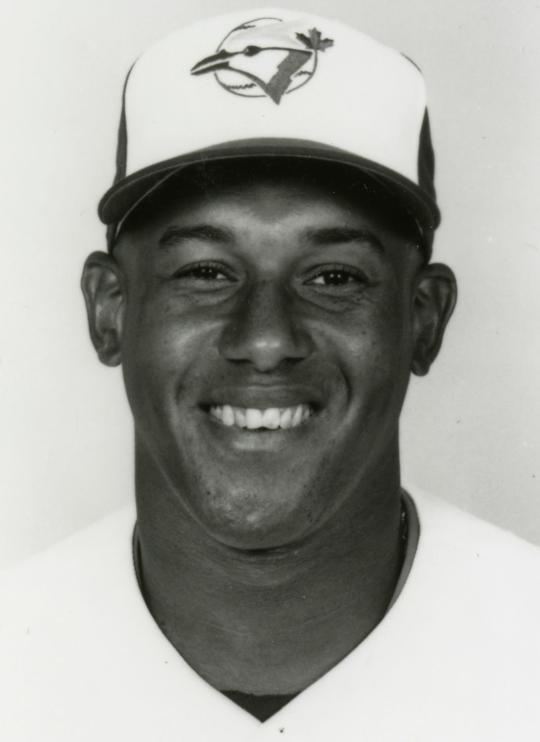

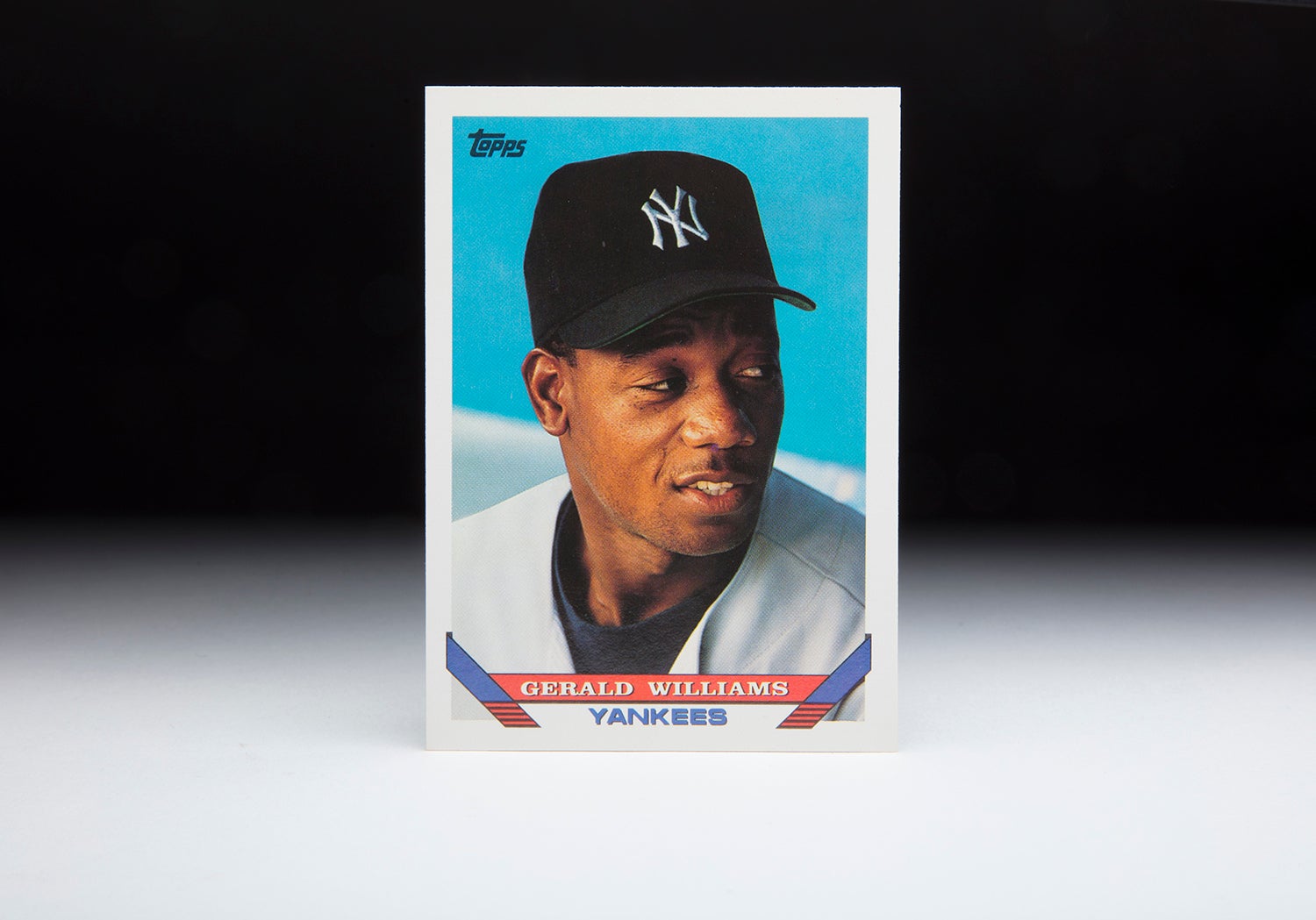

#CardCorner: 1993 Topps Candy Maldonado

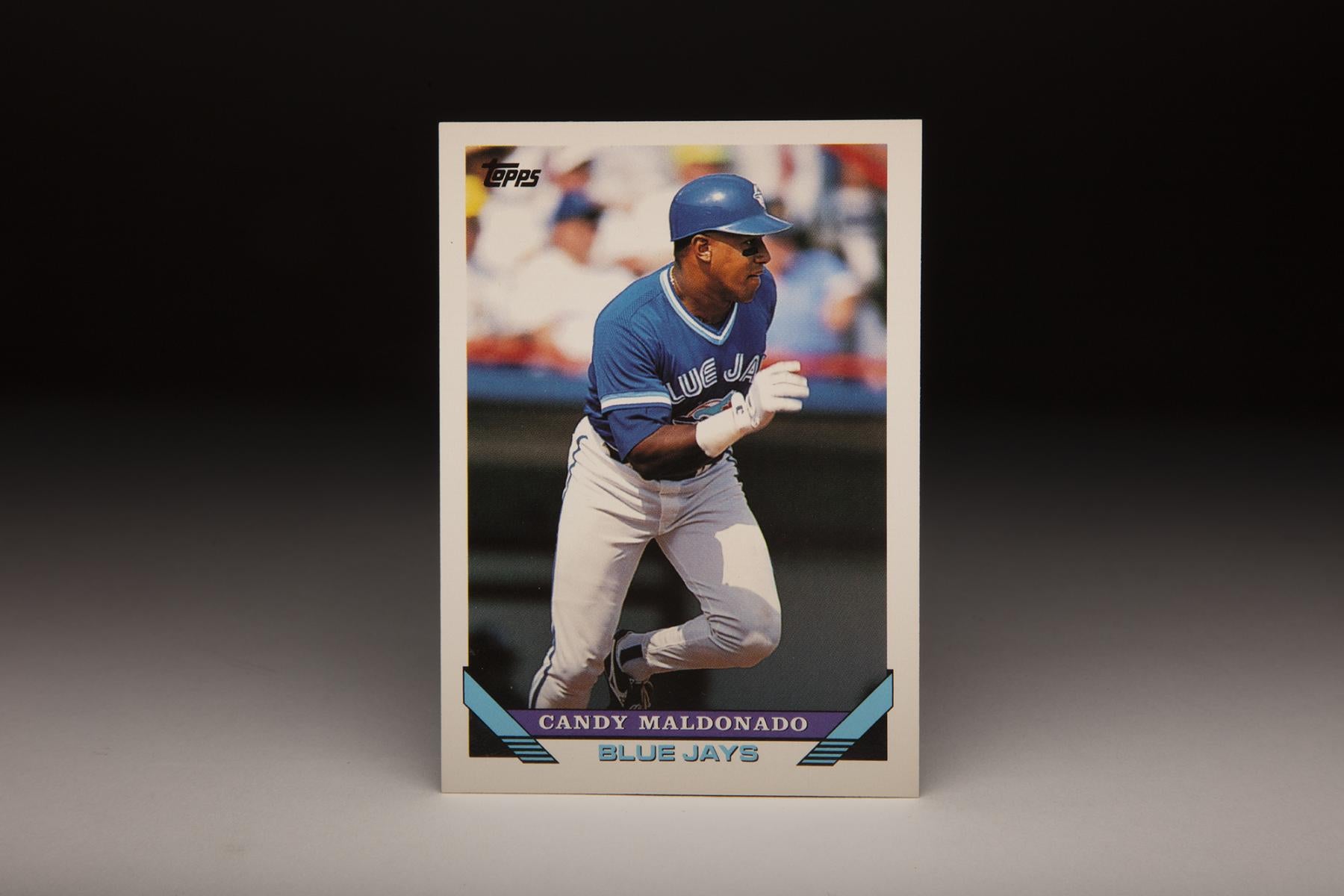

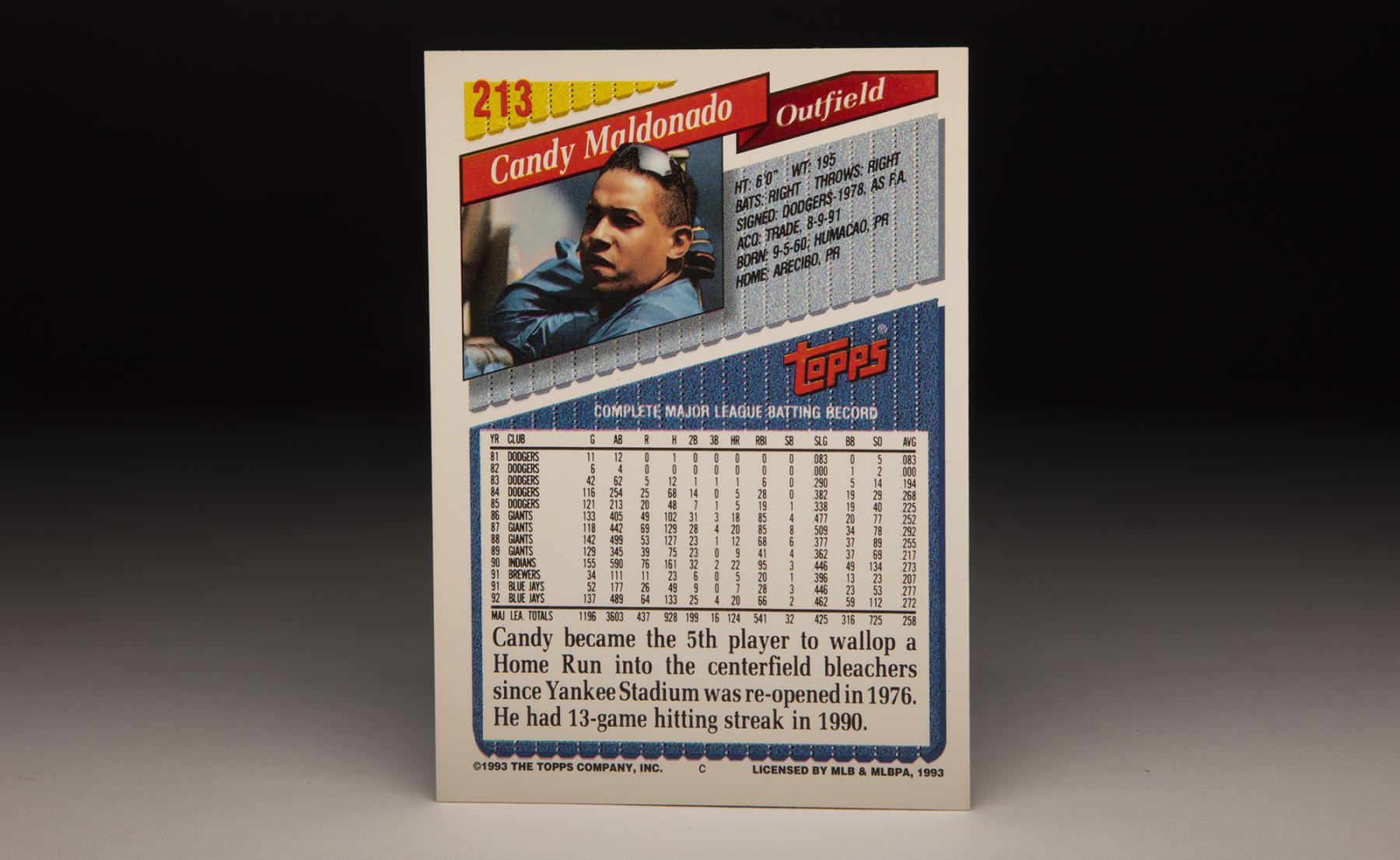

With his broad shoulders and weightlifter’s arms, Candy Maldonado always looked good wearing a baseball uniform. His 1993 Topps card is no exception.

But that card also jumps out for two distinct reasons. First off, there is the batting glove. At first glance, it looked to me like one of those awful rubber gardening gloves my mother used to use when digging up weeds in our front yard. But upon further review, I came to realize that the photo is a bit deceptive. That’s not all glove on Maldonado’s right hand.

The bottom part of what appears to be the glove is actually a wristband. (As evidence, notice the Velcro strap at the wrist, indicating where the glove comes to an end.) With the wristband being the same color and with it overlapping the glove, it only gives the appearance of a long gardening glove.

The seemingly oversized glove and its stark whiteness also bring to mind the iconic look that the late Michael Jackson brought to the musical stage. For most of his solo career, Jackson wore a white glove on his right hand, though his glove was usually studded with crystals. In looking at the Maldonado card, we might expect that once the slugger finishes his at-bat, he’ll grab a microphone from the dugout and start belting out his own version of “Thriller.”

On a more serious note, the Maldonado card also reveals that the veteran slugger was one of the last players to wear a helmet without an ear flap. By 1992, most major league players wore helmets with either one or two flaps, as mandated by the rules of the day. The only players who were allowed to wear flapless helmets were veterans granted an exception because of a grandfather clause. Gary Gaetti and Hall of Famer Tim Raines were two other players from the early 1990s who continued to wear the old-style headgear. Finally retiring in 2002, Raines would become the last player to sport such a helmet. Maldonado would retire the flapless helmet in 1995, when his lengthy and well-traveled career came to an end.

One might also regard the presence of the name “Candy” on a baseball card as somewhat unusual, but it’s really not. Maldonado was known by that nickname his entire career; every one of his Topps cards listed him as Candy. And he’s not anywhere near the first major league player to be called Candy. In the 19th century, Candy was a fairly common nickname for ballplayers. There was Candy LaChance, Candy Nelson and of course Hall of Famer Candy Cummings.

Even into the 20th century, the Candy craze continued. In 1967, a pinch-running specialist named Candy Harris played for the Houston Astros. In 1998, right-hander Candy Sierra pitched for the Cincinnati Reds and San Diego Padres. If there were to be a little bit looser in interpretation, we might also include John Candeleria on the list; he was known for much of his career as “The Candy Man,” a nickname that he shared with Maldonado.

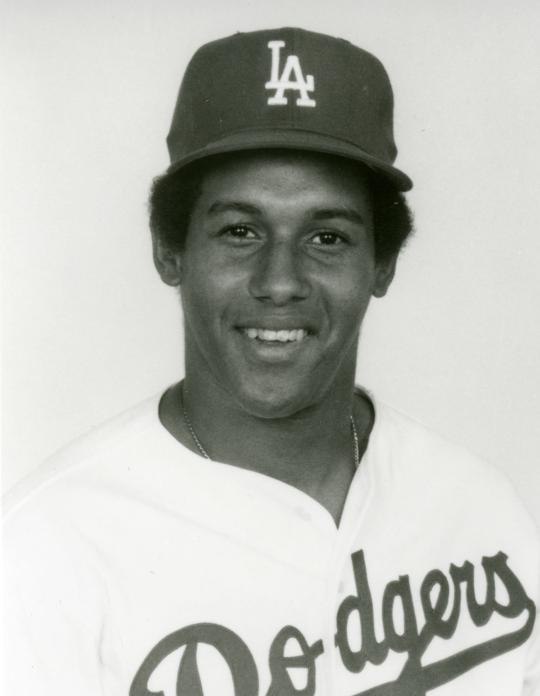

Born Candido Maldonado in Puerto Rico, Maldonado signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers as an amateur free agent in 1978. It did not take him long to establish himself as one of the top hitting prospects in the Dodgers’ organization. After a solid season and a half with the Dodgers’ Rookie League affiliate, he moved up to Clinton of the Class-A Midwest League in the midst of the 1979 season. He struggled there, batting only .234.

Using that experience as a learning tool, Maldonado exploded in 1980 when he moved on to Lodi of the California League. He batted .305 with 24 home runs and 12 stolen bases, numbers that allowed him to take home the league’s MVP Award. The Dodgers bumped him up two levels to Triple-A in 1981, but the double jump did not phase Maldonado. He batted .335 with 104 RBIs for Triple-A Albuquerque, convincing the Dodgers that he was ready for a major league audition, even at the age of 20. In September, the Dodgers brought him up for an 11-game looksee, but he picked up only one hit in 12 at-bats.

With a crowded outfield consisting of Dusty Baker, Ken Landreaux, Reggie Smith and Rick Monday, the Dodgers had no immediate room for Maldonado in 1982. So he went back to Albuquerque, where he continued to hit for average and power. If there was a downside to his game, it was his baserunning. He stole four bases but was thrown out 18 times, accounting for an 18 percent success rate. If anything, the lack of basestealing success taught Maldonado to remain anchored at first base.

More interested in his hitting skills, the Dodgers again called up Maldonado in September. He appeared in six games, and accrued four at-bats, but without a hit.

Maldonado still faced roadblocks in LA. Even with Monday in decline and the Dodgers moving Guerrero to third base, there was still no place for Maldonado to play regularly. But the Dodgers wanted him on the Opening Day roster, so they included him as a backup to Baker and fellow outfield prospect Mike Marshall. Playing sparingly, he batted only .150 over the first two months of the season. In an effort to get him a steady dose of at-bats, the Dodgers sent him back to Albuquerque in June; there he racked up a .318 batting average, earning himself another call up later in the summer. He would hit slightly better for the Dodgers the rest of the way but was unable to raise his batting average to the Mendoza Line.

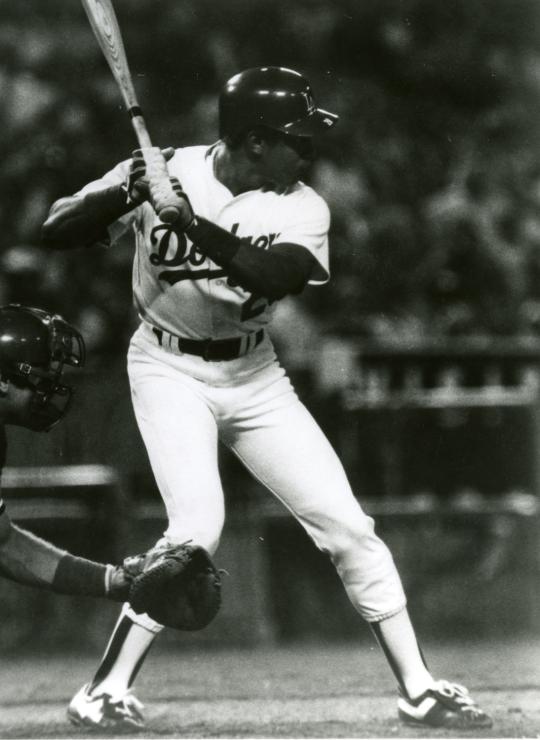

In 1984, the Dodgers made a firmer commitment to Maldonado. During Spring Training, they waived veteran Dusty Baker in order to make room for him in the Dodgers’ outfield. Once the season started, Maldonado played as part of a platoon in right field. He batted a respectable .268, but hit only five home runs and showed little patience (drawing 19 walks). Maldonado’s overly aggressive hitting style did not play well in the major leagues, as pitchers succeeded in making him chase pitches out of the strike zone.

The 1985 season brought more frustration Maldonado’s way. His batting average dipped, while his power output showed no improvement. He eventually lost the right field job to Marshall, who had exceeded him in the Dodgers’ rankings of young prospects.

By this time, both the Dodgers and Maldonado needed a change. In search of some catching help, the Dodgers targeted Alex Trevino of the San Francisco Giants, who asked for Maldonado in return. The Dodgers agreed to the one-for-one swap.

The change of scenery helped revive Maldonado’s career. After starting the season as a pinch-hitter, a role in which he excelled, Maldonado eventually moved into a more prominent position. Giants manager Roger Craig used him as a semi-regular outfielder, allowing him to fill in for Jeffrey Leonard in left field and Chili Davis in right. In 133 games, Maldonado hit 18 home runs and slugged .477, both marks representing major improvement over his struggles in Los Angeles.

Even his final numbers did not tell the entire story of Maldonado’s first season in San Francisco. It was his clutch hitting that became the hallmark of what he did for the Giants in 1986. With two outs and runners in scoring position, he batted .321. He also batted .425 as a pinch-hitter. Thanks in part to his optimal hitting in key situations, he was named the Giants’ most valuable player and finished 21st in the National League’s MVP balloting.

Due to a broken finger suffered in late June, Maldonado played less often in 1987, but more productively. Though he missed six weeks and appeared in only 118 games, he belted 20 home runs, slugged .509 and raised his batting average to .292. He also made a few headlines in early May when he hit for the cycle. With Maldonado supplementing a power-packed lineup that featured Kevin Mitchell and Will Clark, the Giants won the National League West and earned an LCS matchup with the St. Louis Cardinals. Maldonado would appear in five of the seven playoff games, but would pick up only four hits in 19 at-bats, as the Giants lost a hard-fought and evenly-matched series.

It was Maldonado’s defensive play, though, that captured much of the attention in the NLCS. In the second inning of Game 6, Maldonado lost a routine fly ball in the lights, allowing Tony Pena to reach base. Pena then scored on a sacrifice fly, in what turned out to be the only run of the game. Buttressed by a 1-0 victory, the Cardinals then won Game 7 to take the series.

In 1988, Maldonado became the Giants’ everyday right fielder, but his hitting tailed off. The culprit may have been injuries; Maldonado played much of the summer with sore shoulders and aching knees, which affected his swing and his power. With only 12 home runs and an OPS of .688, Maldonado’s season reflected a subpar year for the Giants, who fell to fourth in the National League West.

During the winter, Maldonado dropped 10 pounds and reported to Spring Training in better condition, but the weight loss did not seem to help. Maldonado endured another off season, this one his worst in San Francisco. His batting average fell to .212 and his home run total to nine, even in a season in which the Giants advanced to the World Series. Fans at Candlestick Park began to boo him with regularity. It was a puzzling turn of events for a player seemingly in his prime, still only 28 years of age. The poor season also came at the worst time financially; it was Maldonado’s walk year. Now a free agent, he found little interest on the open market and settled for a bargain basement one-year deal with the Cleveland Indians.

Much like his earlier move to the Giants, the change in scenery (and in this case, a change in leagues) proved the perfect antidote for Maldonado’s career. He exploded onto the American League scene, putting up 22 home runs, 95 RBI and 69 runs scored. After the season, Indians general manager Hank Peters laid heavy praise on Maldonado. “He had a tremendous year for us,” Peters told sportswriter C.W. Nevius. “And he’s a terrific guy. He was durable, worked hard, and was a good influence on the younger guys.”

After the season, Maldonado admitted that he had been hesitant about signing with the Indians, only to have his mind changed. “Cleveland was the last place in the world I wanted to be,” Maldonado told the Indians Ink publication. “But it certainly was not what I had expected. My entire family was very happy here. I’m very happy to be a member of this organization.” As well as Maldonado performed both on the field and in the clubhouse, he found almost no interest on the free agent market.

Even the Indians took a pass on Maldonado, claiming that they wanted to go with speed and youth in the outfield. Some observers felt that Maldonado’s asking price was too high. He reportedly wanted three years and $6 million, a price tag that turned off potential suitors. Other critics cited his continued over-aggressiveness in the plate; even in a good season, he walked only 49 times.

For his part, Maldonado could not understand the lack of interest. “It’s sad. It hurts,” he told Tom Verducci of Newsday. With the Indians choosing to go in other directions, Maldonado remained jobless throughout the winter. He finally signed a one-year deal with the Milwaukee Brewers, but it was a non-guaranteed contract.

Maldonado managed to make the Brewers’ Opening Day roster, but he slumped badly during his Milwaukee tenure while playing sporadically. A broken foot didn’t help the situation, limiting both his playing time and his hitting. With his batting average an uncharacteristic .207, Maldonado found himself on the trading block.

In August, the Brewers sent him to the Toronto Blue Jays for a minor leaguer and a player to be named later. The timing could not have been better for Maldonado. He was joining a Blue Jays team that was attempting to win the American League East title. His new general manager, Pat Gillick, believed that Maldonado might be the antidote to an underachieving offense. “… he’s certainly going to make some good contact, drive in some runs, and give our pitchers more to work with than they’ve had over the last few months,” Gillick told the Associated Press.

Maldonado did all of that – and then some. Serving as the Jays’ principal left fielder down the stretch, Maldonado posted an OPS of .821 in 52 games and helped Toronto finish off a 91-win season and a division championship. He remained the starting left fielder in the ALCS but batted only .100 as the Jays lost the series to the eventual world champion Minnesota Twins. The playoff loss left Maldonado and the Blue Jays with unfinished business – and plenty of motivation for 1992.

His career resurrected in Toronto, Maldonado again played left field, joining an outfield that already had Devon White and Joe Carter. Quietly filling a role on a team filled with stars, Maldonado hit 20 home runs and carved out an OPS of .819. The Jays won their second consecutive division title, four games better than Maldonado’s former team, the Brewers.

Maldonado fared much better in the 1992 ALCS than he had in 1991. Clubbing two home runs against the Oakland A’s, Maldonado piled up 12 total bases and six RBI. The Jays took the series in six games. For the second time in his career, Maldonado prepared to play in a World Series.

He didn’t hit particularly well in the ’92 Series, with only three hits in 19 at-bats, but his ninth inning single in Game 3 brought home the game-winning run. That victory gave the Jays a lead of two games to one over the Braves on their way to the first world championship in franchise history. After more than a decade in the major leagues, Maldonado finally had a World Series ring.

Toronto’s championship coincided with another free agent season for Maldonado. The Jays would have liked to have kept the veteran outfielder and clutch hitter but were outbid by the Chicago Cubs. Unfortunately, Maldonado’s readjustment to the National League did not go as planned. Platooning with left-swinging Derrick May, Maldonado batted only .186 and hit a grand total of three home runs.

He would not last the season in Chicago. In late August, the Cubs traded him to the Indians for fellow slugger Glenallen Hill. Maldonado hit decently for the Indians down the stretch but fell into a deep slump the following spring. The lack of hitting, coupled with the emergence of a young Manny Ramirez, resulted in reduced playing time for Maldonado.

It was also the summer of the strike, which ended the season in August. As a result, Candy appeared in only 42 games, hitting a mere .196. With his contract expiring and the strike lingering into the following spring, Maldonado found himself in baseball limbo.

When the strike finally ended in April of 1995, he soon found work – signing a contract with his old team, the Blue Jays. With a crowded outfield featuring Carter, White, and Shawn Green, Maldonado settled into a fourth outfielder role and played well, posting an OPS of .850. But with the Blue Jays in a rebuilding phase, Maldonado became expendable late in the summer. Just before the Sept. 1 deadline for freezing postseason rosters, the Jays sent him to the Texas Rangers. Maldonado put up an OPS of .913 over 13 games, but the Rangers fell short of both the division title and the wild card.

Once again, Maldonado entered free agency. Still only 34 and seemingly capable of playing as a fourth outfielder and platoon DH, Maldonado surprisingly found no takers on the open market. Rather than try to continue his career in the minor leagues or in a foreign league, he opted for retirement.

Maldonado did not remain out of baseball for long. Always known for being outgoing and well-spoken in both English and Spanish, Maldonado embarked on a second career as a Spanish language broadcaster. He eventually joined ESPN Deportes, where he gained a reputation for insightful analysis and tough-but-fair commentary.

It’s no surprise that Maldonado has found success in his post-playing days. While his early years in the big leagues were difficult ones, he eventually found his way with teams like the Giants, Indians and Jays. And he always cut a distinctive form on the field, with those strange, matching white gloves and wristbands that made him look like he was ready to do a little bit of gardening.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame