- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1993 Topps Gerald Williams

#CardCorner: 1993 Topps Gerald Williams

The 1990s saw some major breakthroughs in the baseball card industry.

With so many companies producing cards and competition fierce, it only made sense that Topps, Donruss, Fleer, and the rest of the competition made improvements to cards.

The various card companies began producing cards on better and glossier stock, featured more and more action cards, and showed off clearer, sharper photography. Given all of these advancements, it’s somewhat ironic that the bottom fell out of the industry by the mid-1990s – the product of a market that was simply drenched with too many cards and too many companies.

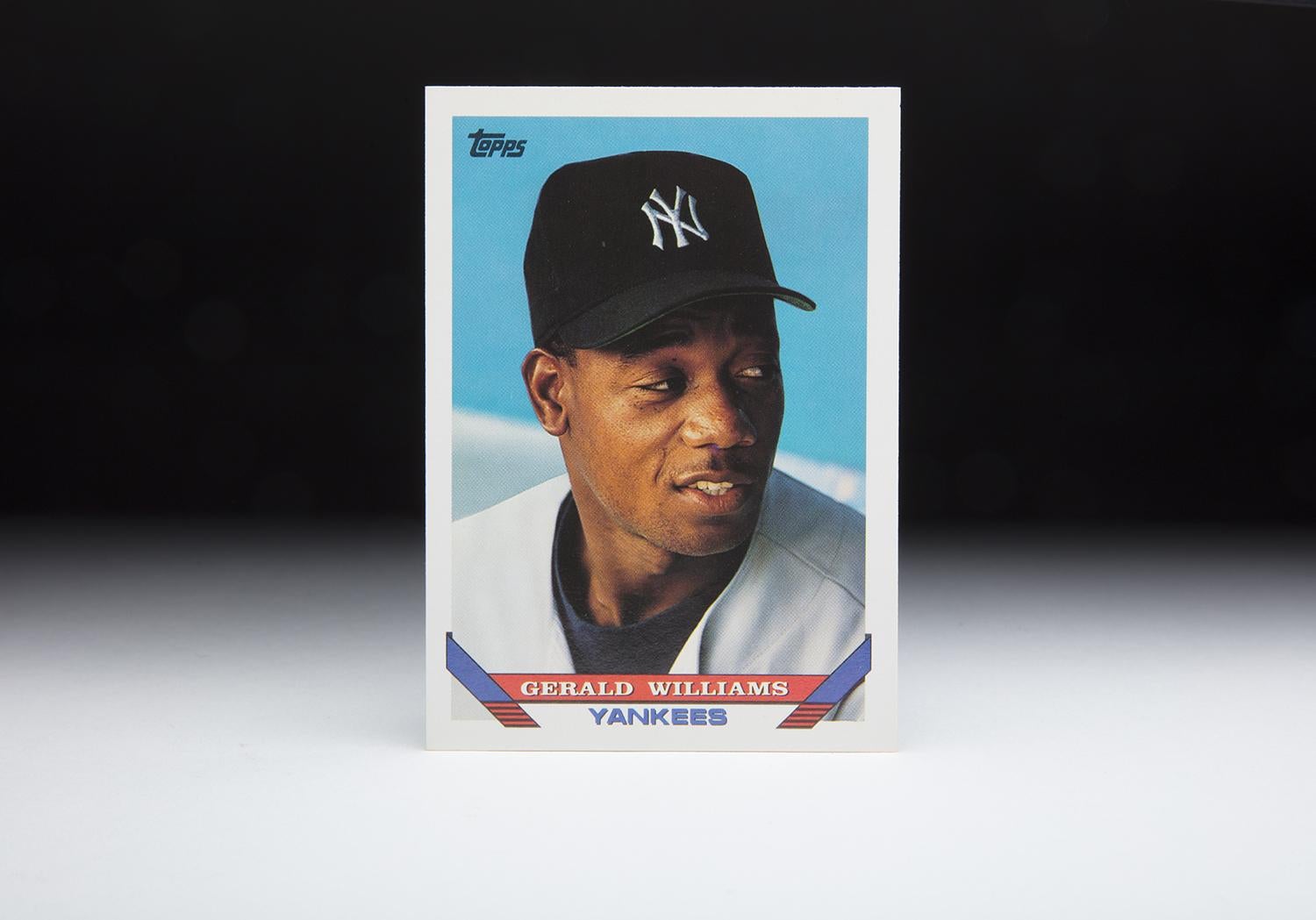

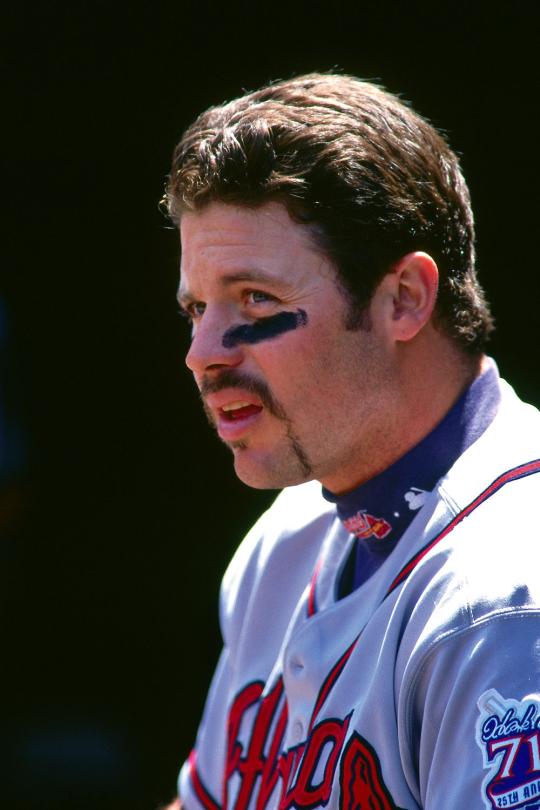

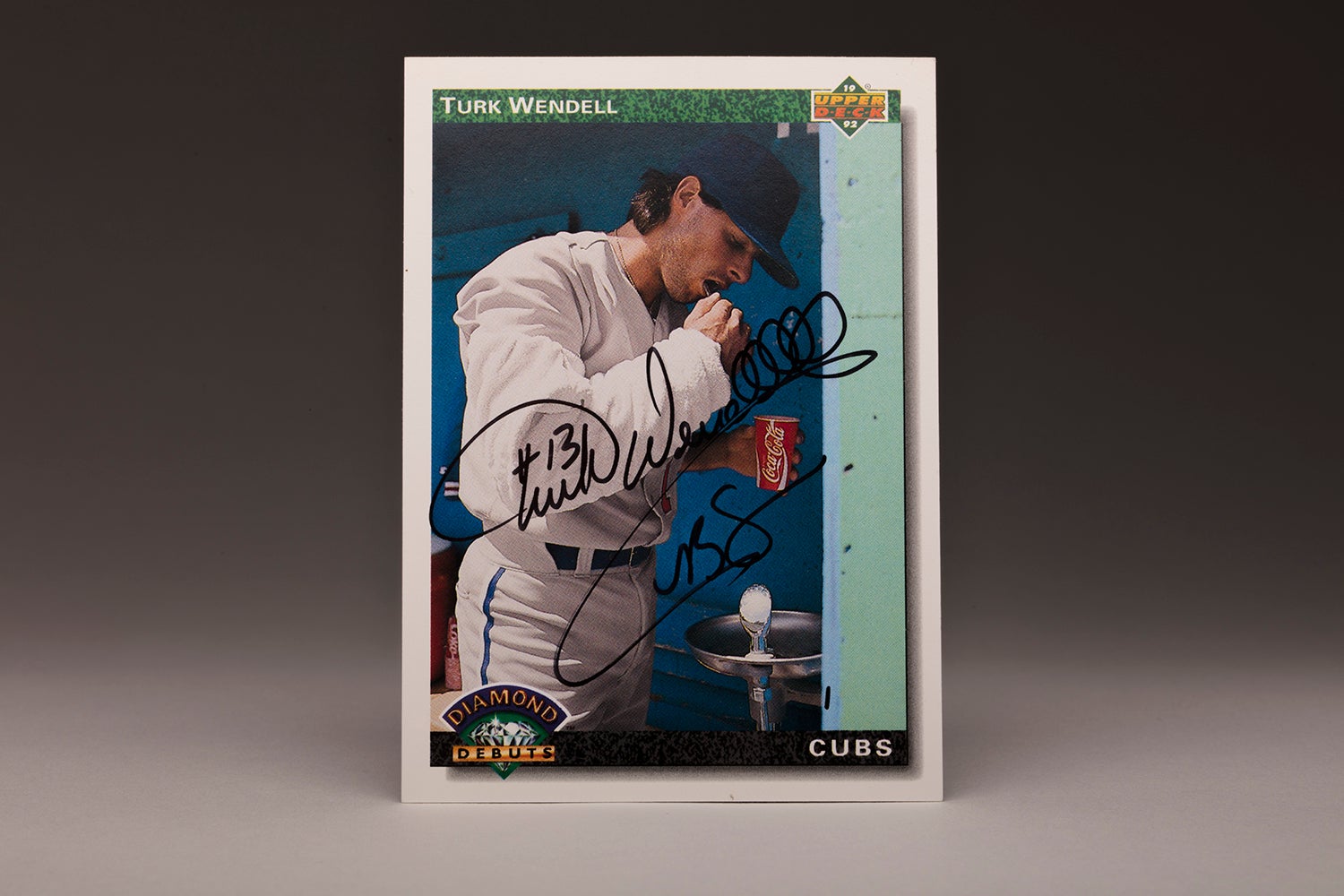

The 1993 Topps set represented one of the better artistic efforts of the decade. With a simple design – a basic, symmetrical banner featuring the player’s name and team near the bottom of the card – and its in-focus photography, ’93 Topps gave collectors an excellent offering. The set featured a ton of action cards, most of which were clear and well-framed, but it’s a simple portrait shot that catches my eyes, making it a personal favorite in a well-rounded and appeasing set.

At first glance, Gerald Williams’ 1993 card might seem unspectacular. It’s a close-up of his face, a basic portrait that lacks any airbrushing or other baseball card oddities that Topps has become known for over the years. Yet, it has a certain artistry, with the dark blue Yankee cap set contrasted against the light blue background of the dugout.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Additionally, it’s not a typical portrait on a baseball card. It is not staged or posed; those kinds of cards can look awkward and insincere. Instead, the Topps photographer captured Williams while he was in the middle of a conversation in the dugout. Instead of looking directly at the camera, Williams’ eyes are aimed to his left, toward the unseen person who is talking with him. His mouth is open slightly, just the way that someone would do while in the midst of conversation. This is far more natural and genuine than the typical close-up of a player who is trying to pretend that he doesn’t notice the cameraman, but clearly does.

In this case, Williams seems oblivious to the photographer; he is clearly more concerned with the unseen teammate or coach who is sharing some time with him on the dugout bench.

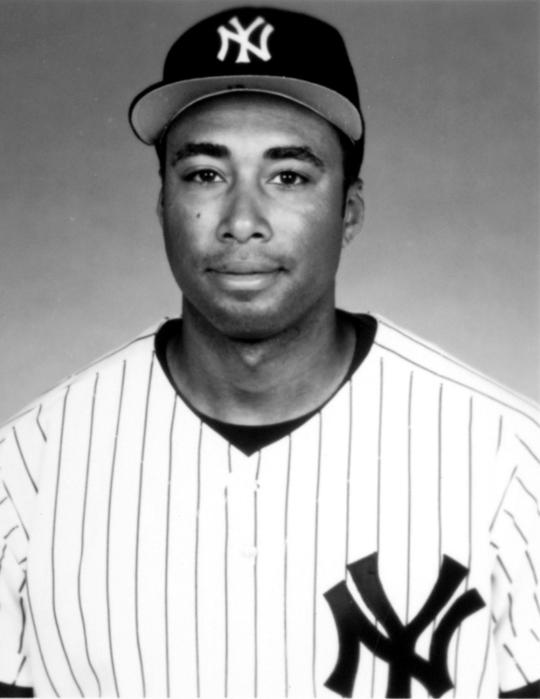

Williams provides interesting fodder for another reason. His career is a classic case of a player caught in between. He joined the New York Yankees in the early 1990s, at a time when the team was rebuilding, but also at a time when the organization was loaded with good young outfield talent. With other youngsters like Bernie Williams in the pipeline, and with Paul O’Neill coming over in a fortuitous trade, Gerald Williams found himself squeezed out of playing time. Never able to secure an everyday job with the Yankees, Williams instead had to settle for a role as the team’s fourth outfielder.

Just when Williams’ sacrifice of playing time might have paid off in the form of an opportunity to play for an eventual dynasty, the talented young outfielder once again found himself the victim of bad baseball luck. In the middle of the 1996 season, with the Yankees on the verge of winning their first world championship since the late 1970s, Williams found the rug pulled out from underneath him when the Yankees dealt him to Milwaukee for left-hander Graeme Lloyd. As a result, Williams never played for the Yankees’ world championship teams of 1996, ’98, ’99, or 2000.

The move out of New York eventually paid off in more substantial playing time, but by then Williams was a bit older, and likely past his prime. Even when he returned to the Yankees in 2001 and ’02, he couldn’t finagle his way onto the postseason roster, denying him the chance for some belated playoff and World Series glory.

None of this should be interpreted as an indication that Williams had a lost career struck down by misfortune. Not at all. Let’s not forget that Williams had the chance to play in the 1999 World Series, appearing for the opposition Atlanta Braves against his former Yankees team. And at his peak, he was an excellent role player, the kind that any team would want heading up its bench.

In some ways, Gerald “Ice” Williams can be seen as an overachiever. Born and bred just outside of New Orleans, he grew up in a crowded house with 12 brothers and sisters. After starring at Grambling State, he was not drafted until the 14th round in 1987, partly the result of him taking up baseball at a late age. As a high schooler, Williams had starred in basketball, but didn’t start playing baseball until his senior year.

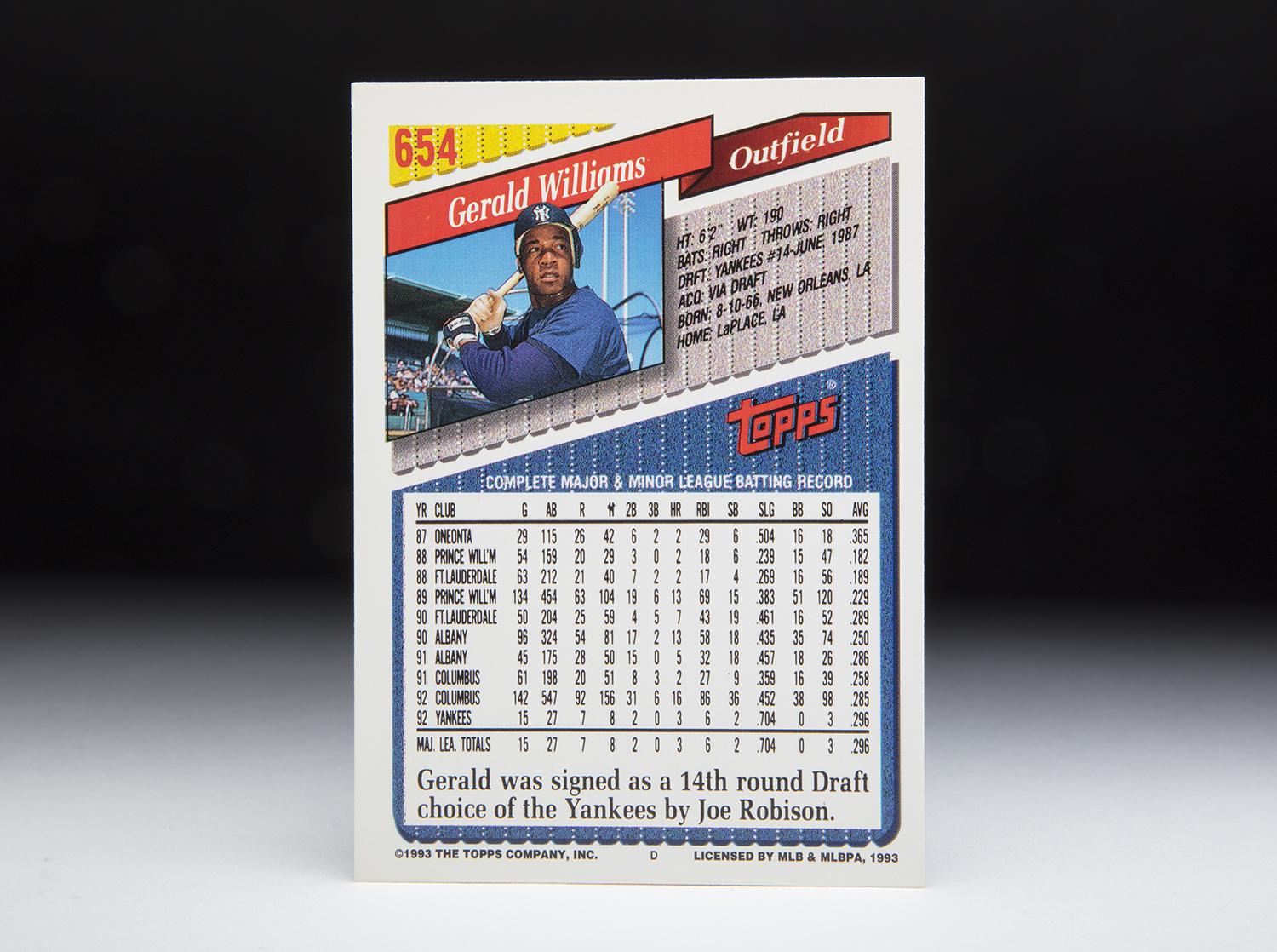

As a collegian, Williams showed off speed and power, but a pronounced hitch in his swing made scouts leery. Still, the Yankees took a chance with their 14th-round selection and assigned him to Oneonta of the Class-A NY-Penn League, where he immediately opened the organization’s eyes by batting .365 in 29 games. Then came a period of struggle. In 1988, he split the minor league season at Class A Prince William and Fort Lauderdale, hitting below .190 at each stop. Returning to Prince William in 1990, he showed some power, but batted only .229.

Facing a crossroads in his early minor league career, Williams responded favorably. After a good half-season playing for Fort Lauderdale, Williams earned a 1990 promotion to Double-A, where he batted .250 with 13 home runs. That performance earned him a ticket to Triple-A Columbus in 1991. After initial struggles at the highest minor league level, he batted .285 with 16 home runs for the Clippers in 1992. That led to his first taste of major league life in midsummer; after nearly six full seasons of minor league ball, Williams finally made it to the show, and did well, batting an impressive .297 in 27 late-season at-bats for the Yankees.

After another year split between Triple-A and the majors in 1993, Williams finally gained a toehold in 1994. The Yankees used him as a fourth outfielder behind O’Neill, Bernie Williams and Luis Polonia. Williams handled the role well, batting .291, posting an OPS of .842, and covered all three outfield spots with finesse. By this point, the Yankees had developed a strong affinity for the athletic outfielder with a chiseled body, and his well-rounded game of speed, power and fielding.

But then the 1994 season came to a premature end, thanks to the player strike that wiped out the balance of the regular season and the World Series. Unable to play baseball, Williams decided to devote his time to speaking to troubled youngsters in his hometown of LaPlace, La. During his talks, which he held with children from both poor families and rich ones, Williams emphasized a simple game plan: Get an education and stay away from drugs.

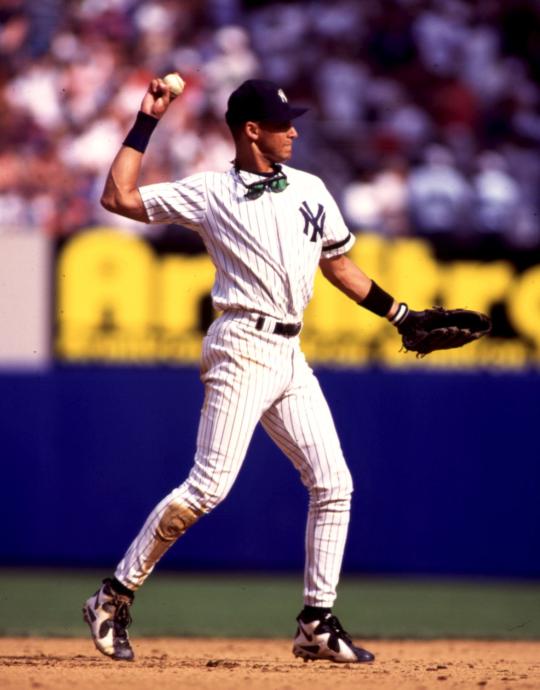

Once the strike came to an end in 1995, Williams enjoyed his best season as a Yankee. Playing in 100 games, he batted only .247 with six home runs, but provided a more intangible boost in another way. It was during that season that Williams took a young shortstop named Derek Jeter under his wing, helping the future franchise cornerstone become acclimated to life in the major leagues. To this day, Williams and Jeter remain close friends, with Jeter once telling Sports Illustrated that Williams “always looked out for me.” Williams also remained close with another teammate, Bernie Williams, a longtime friend since their days coming up through the Yankee farm system.

The 1996 season would turn out to be Williams’ last in pinstripes, at least until he rejoined the franchise after the dynasty years. Although Williams would end up traded in August of ‘96 he turned in a couple of memorable performances for the Yankees before his departure. In a May 6th game against Baltimore, Williams picked up six hits during a 15-inning game, tying a franchise record.

And then on May 14, Williams turned in a great moment defensively. Playing center field behind Dwight Gooden, Williams made an excellent back-to-the-infield catch near the warning track. He then spun and threw to Jeter, who fired to first base to complete a double play. Williams’ circuslike catch in center field preserved a no-hit bid by Gooden, who would finish off the masterpiece eight outs later. Williams’ dramatic catch typified the athleticism he often showed the outfield. It was no wonder that John Harper of the New York Daily News once wrote that Williams played baseball “with a Michael Jordanesque flair.”

It was also during the 1996 season that Newsday published an intriguing feature article on Williams and asked him about any frustration he might have felt in having to put in seven seasons of minor league ball before becoming a fulltime major leaguer. As usual, Williams refused to complain and placed the situation in perspective.

“I’m one of 13!” Williams told writer Barbara Wilder in recalling the crowded house that he had grown up in Louisiana. “I’m pretty hard to discourage. I’m used to having to make sure I concentrate on things that are positive, no matter what the situation, and baseball is a small part of that I’ve had to endure.”

As well as Williams played in a complementary role, he was still a backup on a team deep in outfield talent. That’s why the Yankees gave him up in late August, sending him and reliever Bob Wickman to Milwaukee in exchange for Lloyd. Although the Yankees needed a lefty reliever like Lloyd, the trade was not greeted with applause in the clubhouse. Williams’ close relationship with his teammates, his unceasing professionalism, and his refusal to complain about playing time made him a popular figure at the ballpark.

Williams’ character and makeup played major roles in his teammates’ decision to include him in the rewards that came with a world championship season. Even though the trade prevented Williams from playing in the postseason, his Yankee teammates still voted him a World Series share.

In the meantime, Williams’ tenure in Milwaukee did not turn out well. After batting only .204 over the balance of the 1996 season, he spent all of 1997 in Milwaukee. The Brewers made him their starting center fielder, but he struggled at the plate, hitting only .253 with a paltry 19 walks against 90 strikeouts. Concerned over his lack of hitting, the Brewers traded Williams to the Atlanta Braves for right-handed pitcher Chad Fox.

Only two days later, Williams appeared in a skit on Saturday Night Live, which also featured two of his Braves teammates, Mark Wohlers and Pedro Borbon. Just that quickly, Williams became a little more famous.

With the Braves, Williams not only ratcheted up his fame but also revitalized his career. Platooning with corner outfielders Ryan Klesko and Michael Tucker, he bounced back to hit .305 and post a career-best .856 OPS in 1998. The Braves rewarded him by making him their starting left fielder in 1999. Williams responded to the challenge. Putting in so much work with batting coach Don Baylor that he developed blisters on his hands, Williams hit a respectable .275 with 17 home runs. He also stole 19 bases.

That turned out to be his Atlanta swansong. Now eligible for free agency, Williams cashed in by signing a two-year deal worth nearly $5.5 million with the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. Not only did the Rays offer good money, but they gave Williams a chance to start in center field. Williams hit with power, finishing with 21 home runs, but his lack of patience at the plate (34 walks against 103 strikeouts) remained a career-long concern. And for one of the few times in his career, he became involved in controversy. When Boston’s Pedro Martinez hit him with an inside pitch to lead off a game in September, Williams felt it was deliberate and charged the mound, landing a couple of punches in the fracas. Williams received a five-game ban for the incident.

Williams’ free-swinging style, along with advancing age, caught up to him in 2001. Batting .201 over his first 62 games, the 34-year-old drew his release from the Rays in late June. Five days later, he rejoined his original team, signing with the Yankees as a backup outfielder. But he was clearly not the player he had once been in New York. After batting .170 over the balance of the 2001 season, he went hitless in 17 at-bats in 2002 and drew his release. From there, he bounced to the Florida Marlins in 2003 before finishing his career as a backup with the New York Mets in 2004 and ’05.

By the time that Williams ended his career, he had put in 14 major league seasons with six teams. For some critics, Williams’ career was a disappointment, given his raw talents of power, speed, defense and a strong throwing arm. I look at it a little bit differently.

To me, Williams’ career embodied perseverance. He could have quit after five or six minor league seasons, buried in an organization filled with too many talented outfielders. But Williams, who passed away on Feb. 8, 2022, kept playing, became a valuable contributor to an eventual world champion in New York, put up a couple of above-average seasons for a very good team in Atlanta, and posted a good season in Tampa Bay. Plus, he became close friends with Derek Jeter.

Those are all good, additional reasons for liking Gerald Williams’ 1993 Topps card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame