- Home

- Our Stories

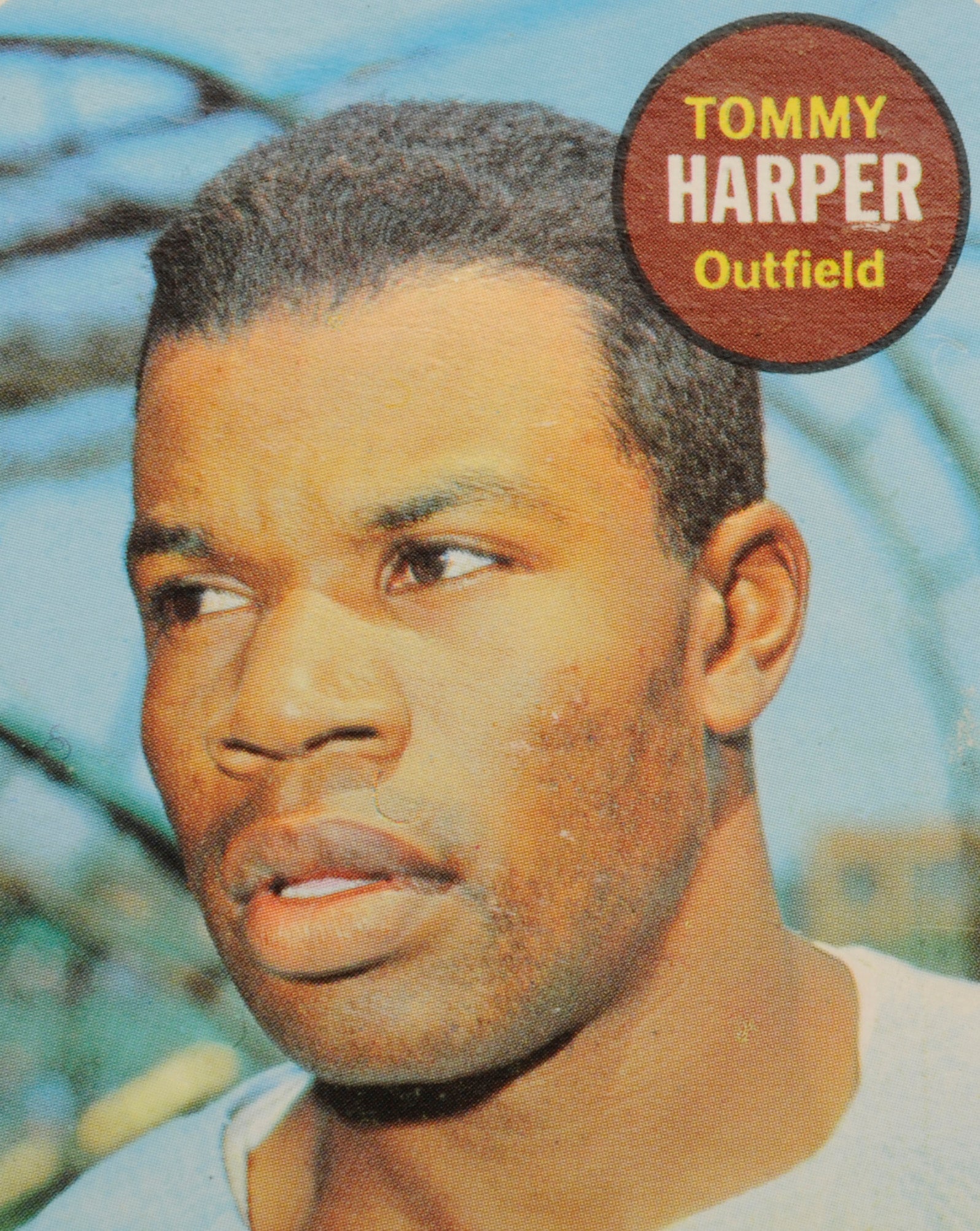

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Hank Bauer

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Hank Bauer

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

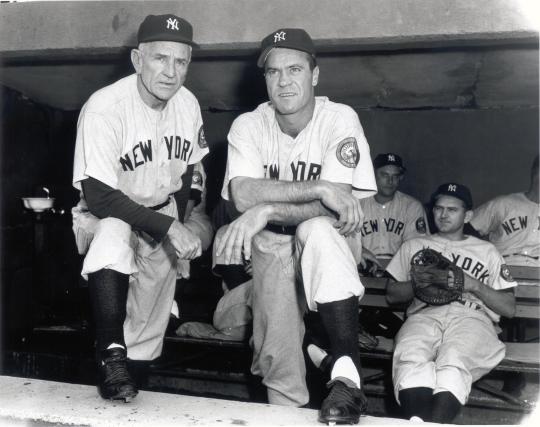

When I first started visiting the Hall of Fame regularly in the early 1990s, I remember seeing Hank Bauer and Moose Skowron, two seemingly permanent fixtures on Main Street.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Year after year, they could be seen signing autographs at one of the local shops. They were always together, always out front of the store, talking to whomever approached them. Even as Bauer’s health declined, to the point that he had to use a voice amplifier to speak with, he continued to make his presence felt. He was a rough and tumble character on the exterior, but one who was always willing to dole out his stories – and his opinions.

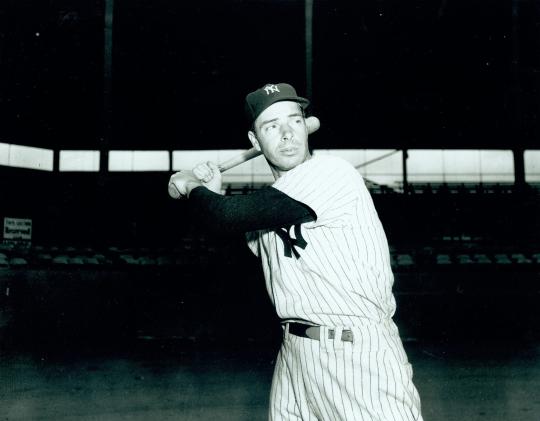

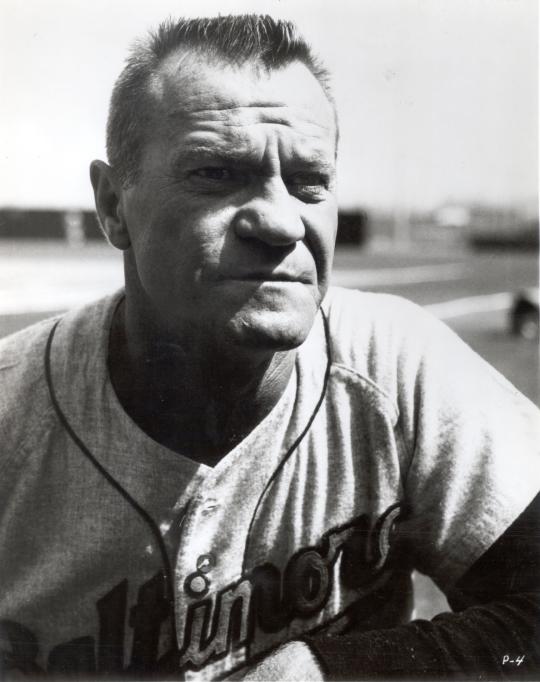

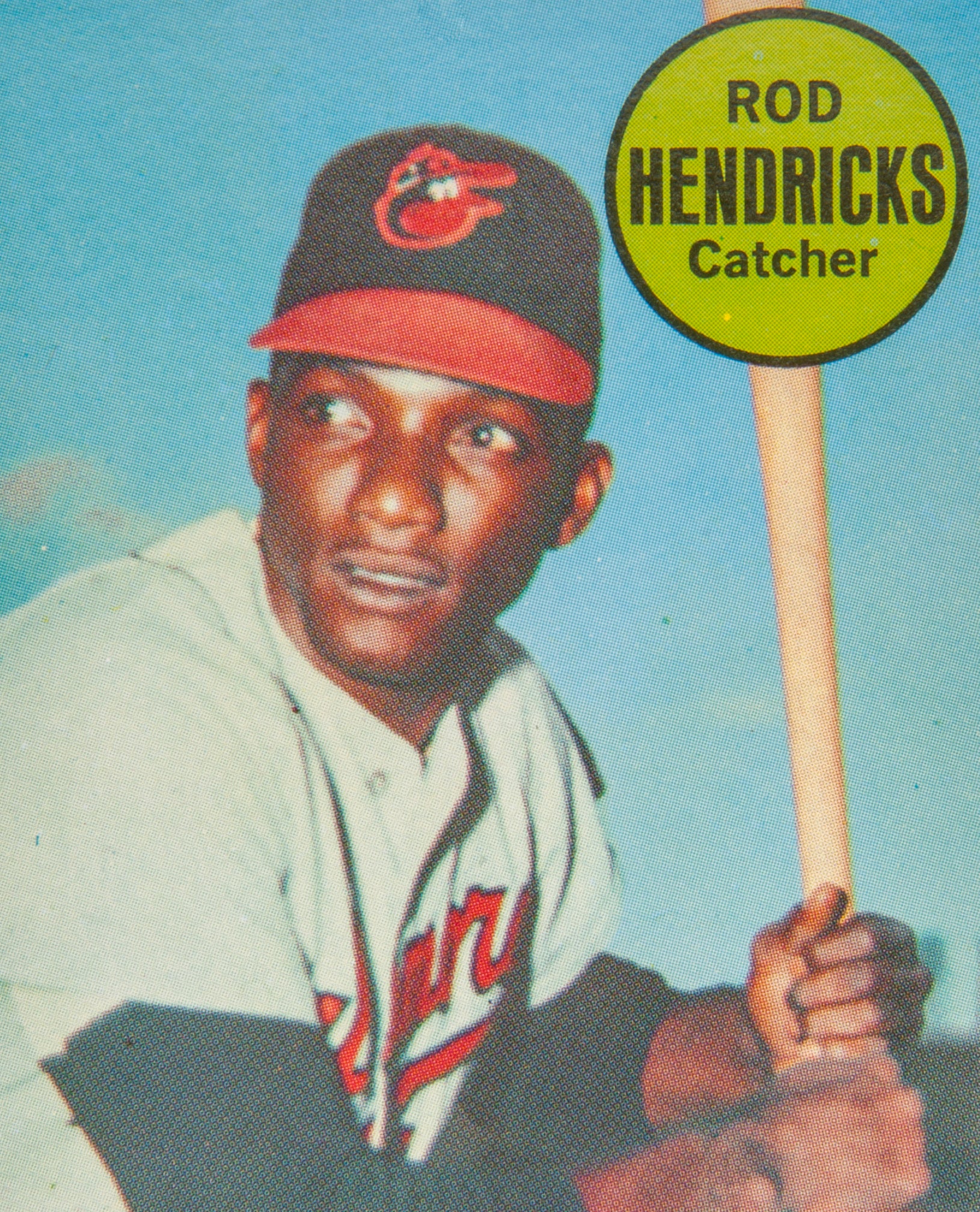

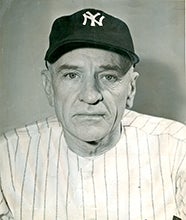

By the 1990s, Bauer looked much different than he did on his 1969 Topps card. He was much thinner in his later years, a combined effect of aging and the lung cancer that plagued him for so many years. Such is the passage of time. In the late 1960s, Bauer was still stocky and strong, a figure who epitomized the word pugnacious. As comedian Jan Murray once said, Bauer had “a face like a clenched fist.” That description certainly fit Bauer’s 1969 Topps card.

What I notice most about Bauer’s 1969 card is the amount of perspiration on his face. When this photograph was taken, likely during the 1966 or ’67 season, he was a good six to seven seasons removed from his playing days. In fact, he was actually managing the Baltimore Orioles, whose uniform can be seen in the photo. So why is Bauer sweating so profusely in this photograph?

I can only imagine that he was the kind of manager who liked to take part in his team’s Spring Training drills, perhaps even take a few swings in the batting cage. Bauer was not the kind of man to stand around and watch others. No, he was the type to set an example, to show his players exactly the way that he wanted things done.

Long before he started managing, long before he even started playing in the major leagues, Hank Bauer lived through the harsh realities of World War II. After playing independent minor league ball in 1941, he joined the U.S. Marines, receiving an assignment to the Pacific Theater, where he served as a gunnery sergeant.

One of the men who served under Bauer lauded him for two of his strongest qualities.

“He was a very fair person,” Steve Fredericks told Berry Federovitch of New Jersey.com. “He was the type of guy who wouldn’t ask you to do something if he couldn’t do it (himself). He was very helpful, the top of his rank.”

Bauer’s temperament also served him well during the war.

“He was a very tough person; very strong,” said Fredericks. “He didn’t take much nonsense.” Bauer’s toughness was on full display in the Pacific, where he suffered from malaria and was hit with shrapnel during a battle in Guam. Later on, during a battle at Okinawa, 58 out of 64 men in Bauer’s platoon lost their lives. Bauer somehow survived the onslaught, but was left with a large hole in his thigh, the result of shrapnel from an artillery shell. When Bauer first saw the gaping wound, he thought he would never be able to play baseball again.

Upon his return to the states, Bauer decided to give up the game and became an ironworker. But a scout for the New York Yankees approached him in 1946 and offered him a contract. With his leg completely healed, Bauer took the offer and reported to Class B Quincy of the Three-I League.

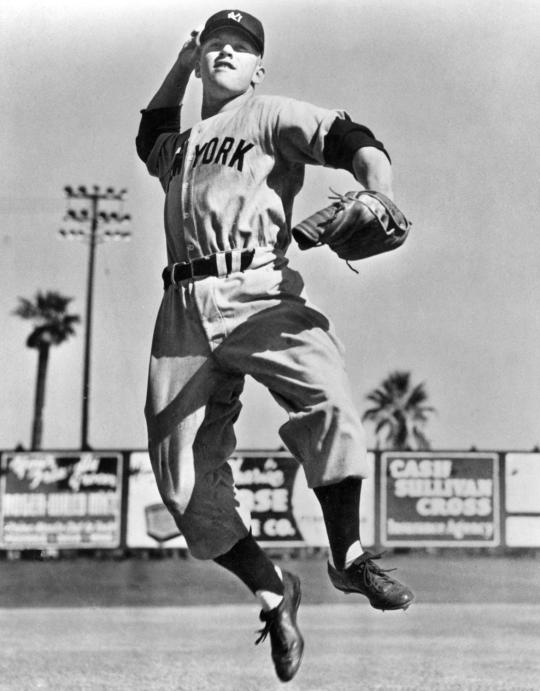

Over the next three seasons, Bauer tore up the minor leagues. Even though he had injured his leg badly during the war, he still ran extremely well. He could also throw and hit with above-average power. Bauer moved up quickly within the Yankee system, reaching Triple-A Kansas City in 1947. After another season with Kansas City in 1948, the Yankees rewarded him with a promotion to New York in September.

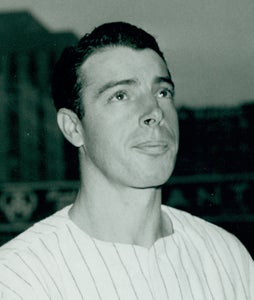

Bauer didn’t hit much in his first taste of the big leagues, compiling just a .180 batting average in 19 games. But the Yankees would find a significant role for Bauer in 1949. With Joe DiMaggio missing the first half of the season due to surgery on his heel, and the team in need of another right-handed hitting outfielder, Bauer stepped in and played center field on a regular basis before shifting to the corners upon DiMaggio’s return. He batted a respectable .272 with 10 home runs, and while those numbers were not overwhelming, they did help the Yankees in their quest to win the American League pennant. Coming to bat six times in a victorious World Series, Bauer made the first of what would be a whopping nine postseason appearances.

Over the next two seasons, manager Casey Stengel used Bauer in an extended platoon role. He played against most left-handers, and occasionally against right-handers.

When Bauer played in 1950, he performed exceptionally, batting .320 with an .843 OPS. He did nearly as well in 1951, as the Yankees added two more world titles to their trophy case.

In 1952, Stengel rewarded Bauer’s effectiveness as a role player by making him the regular right fielder. Bauer delivered a .294 batting average and 17 home runs, while earning his first All-Star Game nod.

At season’s end, the league’s beat writers gave Bauer some consideration for the MVP Award. The Yankees won another World Series, giving Bauer his fourth championship ring.

Bauer and the Yankees weren’t done. In 1953, Bauer lifted his batting average to .304 and his OPS to .841. He also walked 59 times against only 45 strikeouts. Part of a top-flight outfield that featured Mickey Mantle and the underrated Gene Woodling, Bauer contributed to another pennant-winning season for the Bombers. He then played in all six games of the World Series, as the Yankees claimed an unprecedented fifth consecutive world championship.

While Mantle and Berra were the Yankees’ leading stars among their position players, Bauer filled a crucial role as a secondary contributor. He didn’t have as much natural talent as some of the Yankees’ superstars, but no one ran the bases any harder.

“When Hank came down the base path, the whole earth trembled,” Boston Red Sox shortstop Johnny Pesky once told the New York Times.

Bauer became a leader in the clubhouse, taking players like Mantle under his watchful wing. At times, Bauer scolded some of the younger Yankees about staying up too late and overindulging in the night life. As Whitey Ford recalled, Bauer once confronted him by pushing him against a wall and then offering him a stiff warning, “You’re messing with my money.”

Among some of the veteran Yankees, those words would become a rallying cry, a reminder to focus on baseball and to play hard at all times, so as not to jeopardize the players’ chances at postseason shares.

All remained well with Bauer through the end of the 1956 season. Now in his early thirties, he put up higher home run totals in ’55 and ’56, becoming more of a power hitter and less of a contact hitter. After failing to win the pennant in ’54, the Yankees earned two more league titles in ’55 and ’56, while winning it all in the latter season to add to Bauer’s growing collection of World Series jewelry.

The 1957 season brought controversy to Bauer and the Yankees. On May 15, he and several other Yankees attended a birthday celebration for Berra and Billy Martin at the famed Copacabana nightclub. During the night, a drunken member of a local bowling team began to taunt nightclub singer Sammy Davis, Jr. with racial slurs.

At least one of the Yankees intervened, defending Davis and flooring the drunk with a punch to the nose. The recipient of the punch claimed it was Bauer, a charge that the Yankee outfielder denied. Bauer also told reporters that Martin was not involved, as had been rumored.

Bauer’s claims did not dissuade a New York City newspaper from running a headline the next day: “Bauer in Brawl.” The man who had been punched filed charges against Bauer, forcing him to report to the police station for a formal booking, including fingerprinting. A grand jury later dismissed the charges against Bauer, but the public relations damage had already been done.

A few days later, Yankee GM George Weiss punished Martin by trading him to the Kansas City Athletics. Bauer remained a Yankee, putting up good numbers in 1957 before starting to show significant decline in ’58 and ’59.

After the 1959 season, Weiss began exploring a deal with Kansas City, a frequent trade partner. The talks centered around Roger Maris, a young left-handed slugger who had made the All-Star team in 1959. In order to acquire Maris, the Yankees assembled a package that featured several veterans, among them Don Larsen and Norm Siebern. Bauer was included in the deal that brought Maris and shortstop Joe DeMaestri to New York.

The trade crushed Bauer, who had hoped to remain a Yankee for life. He became a part-time player in Kansas City, putting up decent numbers, but for a team far from contention.

He spent nearly two seasons in the shadows with the A’s, when something strange happened.

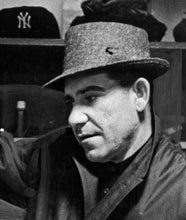

It was during the 1961 season that the A’s announced a major change within their organization. It actually occurred in the middle of a game, when the public address announcer stunningly declared: “Hank Bauer, your playing days are over. You have been named manager of the Kansas City Athletics.” A’s owner Charlie Finley had reportedly not even consulted Bauer about the possibility of managing. Bauer had no real desire to manage, but figured that it was better to manage and have a job than incur the wrath of Finley and be unemployed.

Bauer finished out the season in the dugout, and then managed all of 1962, but the A’s didn’t have much talent. Additionally, Finley made life difficult for Bauer by dictating lineup changes and strategical decisions. After a ninth-place finish that season, Bauer delivered an announcement of his own: He was resigning his position as A’s manager.

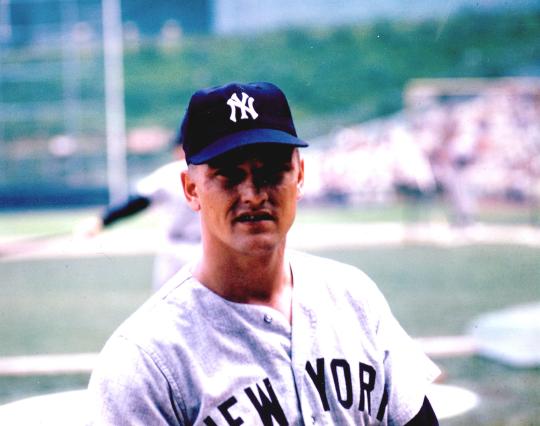

Bauer soon found work as a coach with the Orioles, where he worked under manager Billy Hitchcock. After two lackluster seasons, the O’s fired Hitchcock and turned to Bauer, who managed far differently from his laid-back predecessor. He expected his players to run every ball out and play hard; anything else Bauer would have regarded as an embarrassment to the organization. While a few players balked at Bauer’s simple demands, most considered him fair in his approach. If they worked and played hard, they would have no trouble with Bauer.

In 1964, Bauer’s first season as Orioles manager, the team played well and took over first place for a while, holding onto the lead in early September. Just when it appeared the Orioles might take the pennant, a furious stretch run by the Yankees changed the outlook of the race; the Orioles settled for a third-place finish. But the 97-win total was a huge improvement for the O’s, and a testament to Bauer, who was named the American League Manager of the Year.

After another good season in 1965, a summer that saw the team win 94 games, Bauer and the Orioles reached higher ground in 1966. Bolstered by the off-season acquisition of Frank Robinson, who would win the Triple Crown, the Orioles claimed the American League pennant by a nine-game margin. After the season, Bauer would take home Manager of the Year honors.

The Orioles entered the World Series as underdogs against the pitching-rich Los Angeles Dodgers, but the predictions of Dodger superiority turned out to be inaccurate. Not only did the Orioles win the Series, but they swept all four games, giving Bauer his first World Series ring as a manager – to go along with the seven from his playing days.

Like many championship teams, the Orioles struggled in their efforts to repeat. A number of injuries to their pitching staff, along with a bout of double vision suffered by a beaned Frank Robinson, led to a disappointing season. With Bauer put on notice that winter, the 1968 season loomed as crucial. A rough first half of the season put the Orioles 10-and-a-half games back of the league lead. At the All-Star break, general manager Harry Dalton called Bauer into the office and informed him of his firing. In Bauer’s place, the O’s tabbed Earl Weaver, who had served as one of Bauer’s coaches.

Almost immediately, rumors circulated that the expansion Kansas City Royals would hire Bauer as their first manager. Instead, the Royals tabbed Joe Gordon, the former All-Star second baseman and future Hall of Famer.

With that avenue closed, Bauer accepted an offer from his old boss, Charlie Finley, to become the manager of the recently transplanted Oakland A’s.

With no opportunity to capture Bauer wearing his new Oakland threads, Topps dove into its archive for an old photograph of a capless Bauer wearing the uniform of the Orioles.

Under the direction of Bauer in 1969, the A’s played well, holding first place for a span of more than 30 days. But when the team fell out of the top spot in September, Finley fired Bauer, despite his winning record of 80-69.

Bauer spent the 1970 season on the sidelines, before being hired to work in the farm system of the New York Mets. As a skipper in the Mets’ system, Bauer won the Minor League Manager of the Year Award. He hoped that a major league team would take notice and hire him, but no one did. At that point, Bauer decided to retire from managing.

Bauer returned home to own and operate a liquor store for the next several years. In 1978, Bauer returned to baseball, this time to his beloved Yankees. He would serve the Yankees as a scout before retiring to a life that included appearances at fantasy camps and autograph signings.

A longtime smoker of cigarettes, Bauer was diagnosed with lung cancer in his later years. He succumbed to the disease in 2007, at the age of 84.

For Bauer, it was an eventful 84 years, including his heroism in World War II, all of those World Series wins with the Yankees, the Copacabana incident, another championship as a manager, and the day-to-day soap opera with Finley. Given all of his travails and triumphs, it was no wonder that Bauer’s face on 1969 Topps took on the look of a clenched fist, full of perspiration, but with a trace of a smile.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame