- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Wayne Causey

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Wayne Causey

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

When I first started collecting cards, I would occasionally stumble on an older card of a player I never saw play. One of those players was Wayne Causey, whom I spotted on some oversized baseball cards that my father had collected back in the mid-1960s.

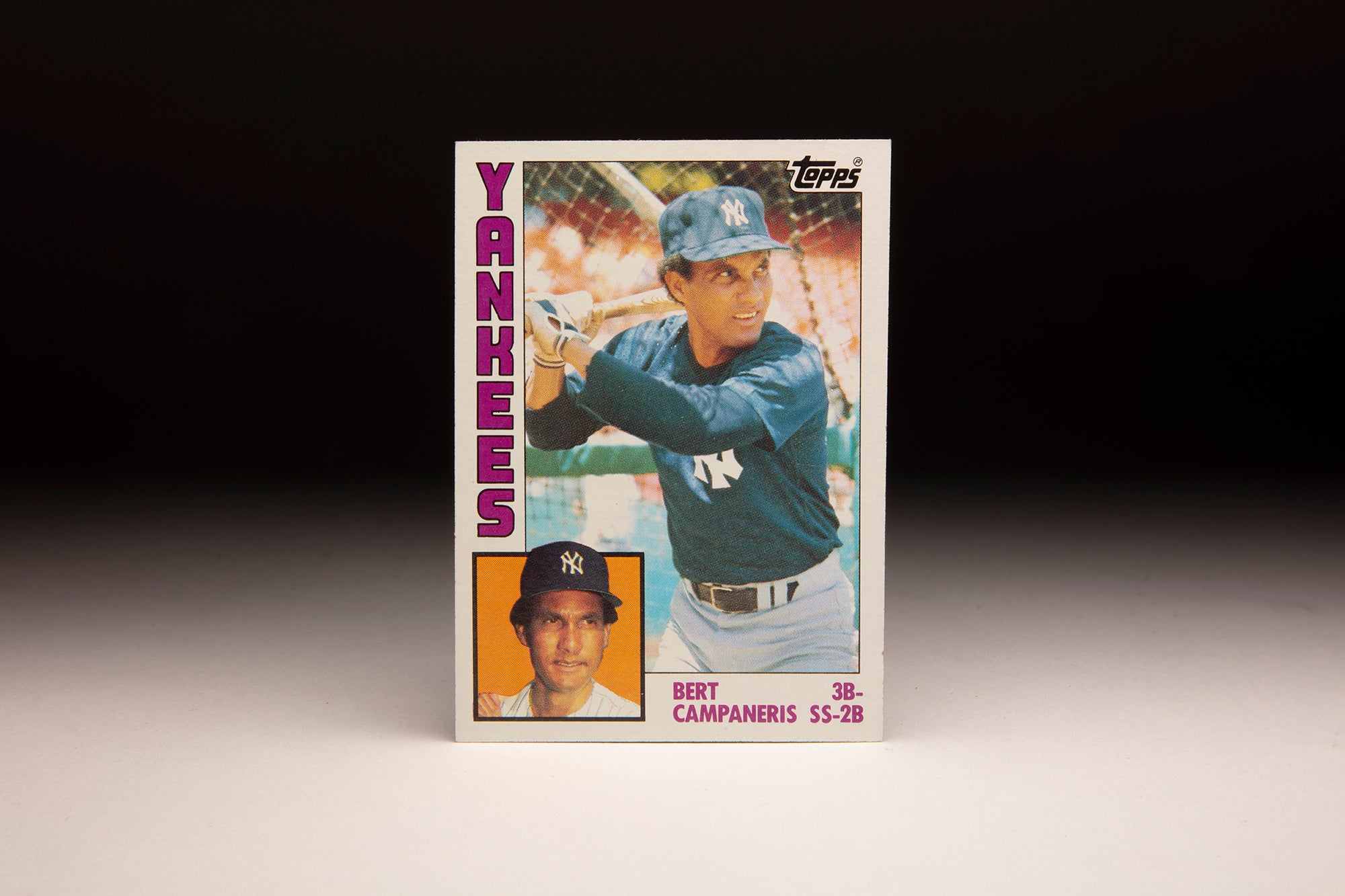

I didn’t know much about Causey; in fact, I wasn’t even sure how to pronounce his last name. (It’s KAW-zee, by the way.). I did eventually figure out that he was the Kansas City Athletics’ regular shortstop before Bert Campaneris arrived on the scene. I also noticed that Causey batted left-handed. Most shortstops of that era batted right-handed, but Causey was one of the exceptions to that unwritten and nonexistent rule.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

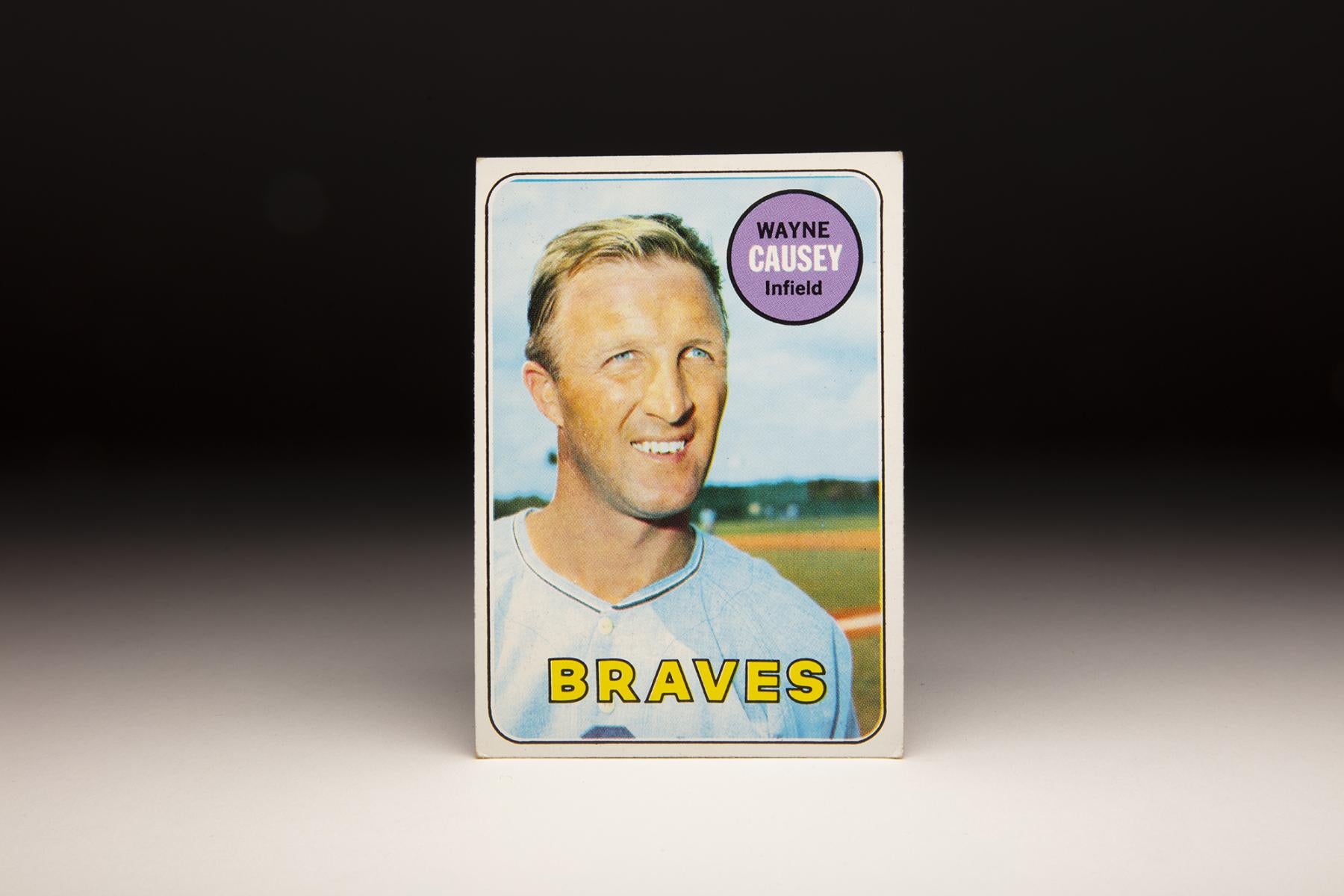

After that, I forgot about Wayne Causey, at least for the most part. I’ve never really written about him or looked deeper into his career and life. But then a few weeks ago, amidst the thousands of cards that have been donated to the Hall of Fame in response to our new “Shoebox Treasures” exhibit, I found a card of Causey that I had never before seen. It’s actually his final Topps card, taken from the 1969 set, a card that shows him as a member of the Atlanta Braves.

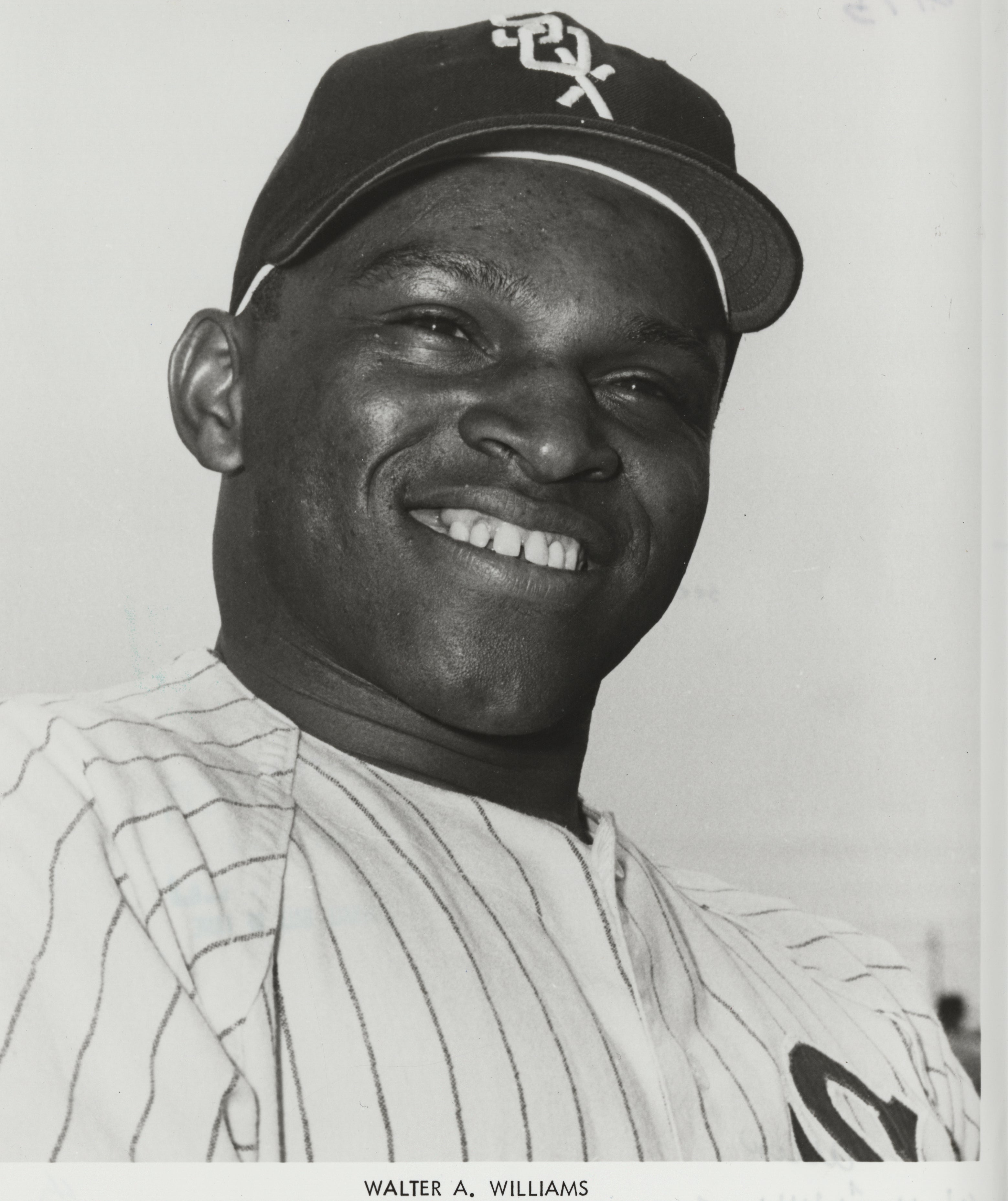

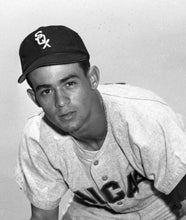

Like a lot of the photography in the 1969 set, the photo is outdated, probably snapped two or three years earlier, when Causey was still playing for the Chicago White Sox. The photo might be an old one, but it caught my attention. It’s a nice photographic image, and one that is neatly positioned on the card, so that Causey’s face and head are seen on the top left, with just enough room for the circular, lavender-colored nameplate on the right. The photo seems to have been shot with excellent natural lighting on a partly sunny day, with a cheery blue sky background from an unknown Spring Training site somewhere in Florida.

The well-framed portrait shot of Causey makes him look energetic, enthusiastic and in good health. He seems to have a nice lean physique, perfect for playing a demanding position like shortstop or second base. His teeth are glowing white, in contrast to other players of his era who perhaps chewed too much tobacco or bubble gum for their own good.

Causey is giving us what might be described as a half-smile, but it looks genuine, and not fake or exaggerated. Causey seems quite happy with where he is, during a light workout on a typical day in Spring Training, which is one of the best times of the baseball calendar. And why wouldn’t Causey be happy, knowing that he is ready to embark on another season of playing a game that he loves, even if he’s not quite the player he once was?

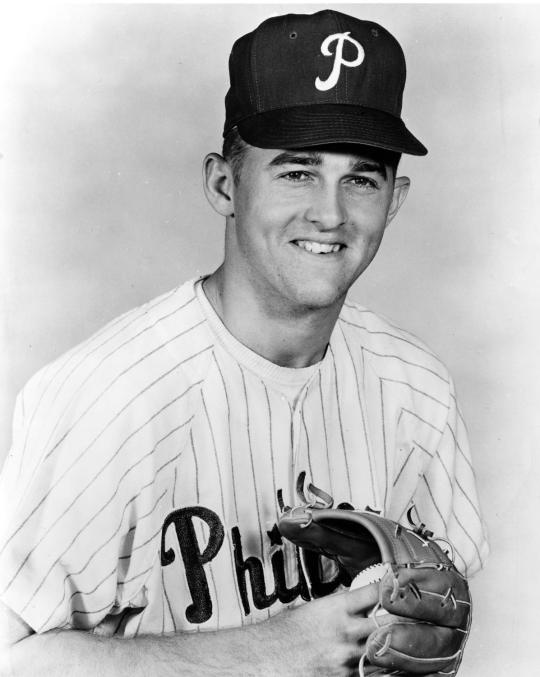

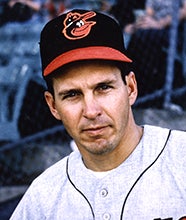

By the end of his career, Causey was grappling with the task of hanging on to a job, but at the beginning, he was regarded as an elite prospect. In 1955, a younger Causey was a highly sought-after third baseman out of Neville High School in Louisiana. The Baltimore Orioles, who did not yet know what they had in an 18-year-old Brooks Robinson, wanted Causey so badly that they outbid the Detroit Tigers and Philadelphia Phillies and gave him a bonus of $32,000. Under the rules of the day, a player receiving a bonus of more than $4,000 was considered a “bonus baby” and thereby had to be kept on the major league roster for all of his first two seasons. In retrospect, the rule was harmful to young players, in that it forced teams to keep players lacking in major league readiness on the roster, unable to hone their skills in the minor leagues.

Remarkably, the 18-year-old Causey was one of five bonus babies that general manager Paul Richards kept on the roster in 1955. The O’s used the teenaged Causey sparingly as a utility infielder, playing him at third base, second base, and shortstop; not surprisingly, he was overmatched at the plate and batted .194 and .170, respectively, over his first two big league seasons. In later years, Causey admitted that he didn’t belong.

“Richards wanted to give me an opportunity to get my feet wet,” Causey once told author Brent Kelley. “No doubt about it, I was over my head.”

The rules finally allowed the Orioles to send Causey to the minor leagues in 1957, his third professional season, but the team strangely kept him in Baltimore for the month of May.

He hit just .200 and received a ticket to Double-A San Antonio ball in early June, remaining there for the balance of the season. Causey endured a terrible season-opening slump in San Antonio, but his manager, Joe Schultz, stuck with the young infielder. Causey eventually came out of hitting doldrums and lifted his batting average to .247, which was not particularly eye-opening but represented major improvement from his difficult start.

As it turned out, Causey would never again appear in an Orioles uniform. For the next three seasons, he spent all of his time at Triple-A, first at Louisville and then for two seasons with Vancouver of the Pacific Coast League. Even with more experience, Causey continued to flounder as a hitter. After batting in the .240 range his first two seasons in Triple-A, he managed to raise his batting average to .265 and draw 66 walks in 1960. But his power remained lacking, as evidenced by a total of only five home runs. To complicate matters, the Orioles began to move him around the diamond, using him as a third baseman/outfielder in ’59 and then trying him out as a pitcher for 10 games in 1960.

Causey didn’t take well to the pitching experiment, giving up 11 earned runs in 19 innings for Vancouver. That winter, Causey continued to take college classes, as he made his way to a degree in accounting. In the midst of taking his finals in late January, Causey received a phone call from the Orioles. The team told him that he had been included as part of a five-player package sent to the Kansas City Athletics for two outfielders, Whitey Herzog and Russ Snyder.

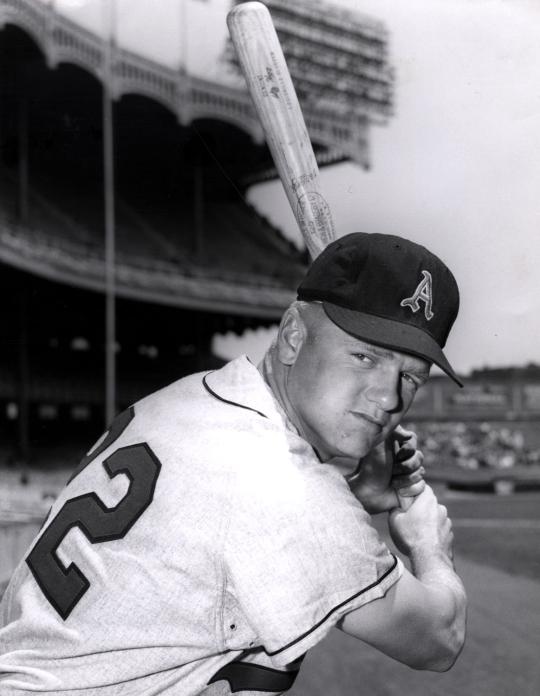

The A’s of the early 1960s were a non-contending team, but they needed help on the left side of the infield, and that guaranteed Causey a spot on the Opening Day roster. With slick-fielding Dick Howser and Rene Bertoia at third, the A’s decided to use Causey as a backup to start the season. That would soon change.

In June, the A’s fired manager Joe Gordon and replaced him with Hank Bauer, who quickly informed Causey that he would now be starting at third base. Causey responded to the challenge by hitting a respectable .276 and hitting eight home runs over the balance of the season.

In 1962, Causey injured his shoulder and headed to the disabled list, giving minor league journeyman Ed Charles a chance to play third base. By the time that Causey returned to the active roster, Charles was entrenched at the hot corner, leaving Causey the odd man out. But in August, Howser went down with a broken thumb, opening shortstop for Causey, where he remained the rest of the season. Causey’s offensive numbers took a downturn – he hit only .252 with four home runs – but he did reach base at a respectable clip of .340 while playing a solid shortstop.

In the spring of ’63, Causey returned to a utility role, behind Charles and Howser. Then came a bad break for Howser, one that opened the door for Causey. During the early days of the season, Howser tore cartilage in his rib cage while taking extra batting practice. Causey moved into the starting lineup and played so well that manager Eddie Lopat wouldn’t think of taking him off the position.

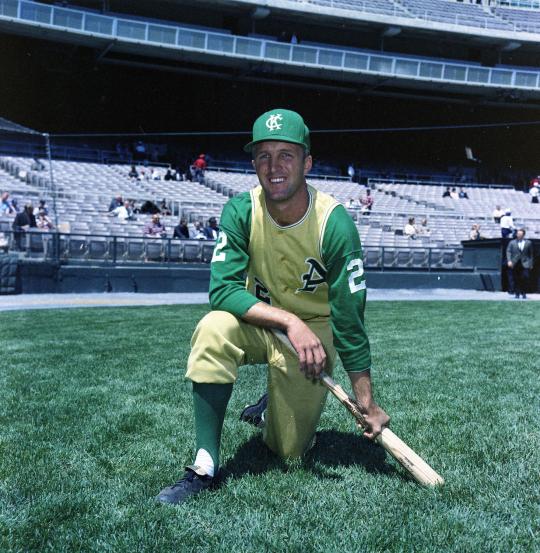

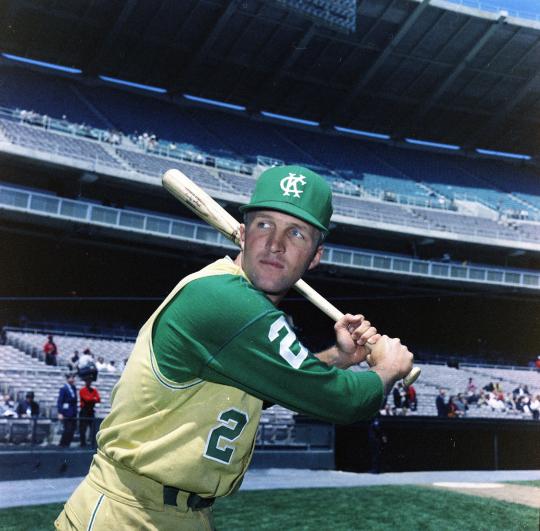

Becoming Kansas City’s everyday shortstop, Causey improved all of his offensive statistics that summer. He lifted his batting average to .280, drew 56 walks against 54 strikeouts, and hit eight home runs. Coupled with his defensive play, that kind of production made Causey a significant asset. In fact, American League writers rewarded him with some surprising support in the MVP voting. Causey finished 21st in the balloting, putting him ahead of three brand name shortstops in Luis Aparicio, Jim Fregosi and Tony Kubek.

Convinced that they had their shortstop of the future, the A’s traded Howser to Cleveland that winter. Knowing that he now had the job all to himself, a more confident Causey blossomed in 1964. He batted .281, drew 88 walks, compiled a .377 on-base percentage and hit eight home runs. Once again, Causey received some back-of-the-ballot MVP support, finishing ahead of Aparicio in the final vote count. Among league shortstops, only Jim Fregosi and Ron Hansen finished ahead of Causey in the MVP sweepstakes.

Causey also showed himself to be a tough player, one who did not want to come out of the lineup with a minor injury. In a game on July 22, he suffered a slightly hyperextended left elbow. Manager Mel McGaha decided to rest him in the second game of a doubleheader, leaving Causey annoyed.

“He asked me if I could play, and I told him I was ready,” Causey told Joe McGuff, corresponding for the Sporting News. “But then I didn’t start. I don’t know why.”

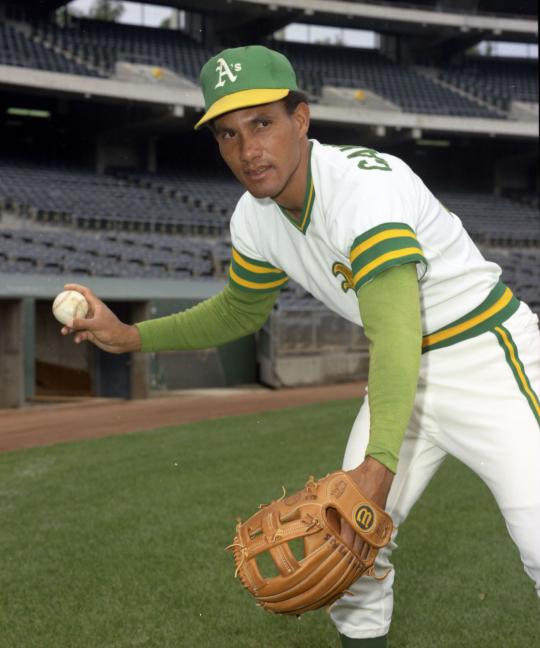

After his peak performance of 1964, Causey would suffer a regression in 1965, in part because of a separated shoulder that affected his play. The emergence of a new shortstop, Bert Campaneris, also played a role in Causey’s falloff. With Campy at short, Charles at third and Dick Green at second, Causey had to settle for more irregular playing time. He still appeared in 144 games, but the constant switching from short to second to third seemed to have a damaging effect on his hitting. For the season, he batted a mediocre .261 with three home runs.

Campaneris was five years younger, had game-breaking speed and projected as a better offensive player than Causey. When the veteran infielder endured a slow start to the 1966 season, he became obvious trade bait. In late May, the A’s made a deal, sending Causey to the White Sox for corner infielder Danny Cater.

Causey found out about the deal in rather roundabout fashion. While sitting in the dugout in the third inning of a game, A’s pitcher Fred Talbot told Causey that he been traded. Causey asked Talbot how he knew; Talbot said the batboy had told him. Causey then made his way over to the batboy, asking him where he learned about the trade. The batboy explained that a policeman had told him about in the clubhouse. And how did the policeman know? Well, he had heard it on the radio. Somehow, no one within the A’s organization had officially informed Causey of the trade.

With the White Sox, Causey became the team’s regular second baseman. He played very well defensively, but his hitting lagged behind. He hit .244 for the Sox without a single home run. The lack of power indicated that his once-separated shoulder had taken its permanent toll.

Heading into the 1967 season, Causey was still only 30, giving the Sox hope that he might bounce back offensively. He didn’t. Instead, his batting average fell off to .224, the lowest of his career since his early days in Baltimore. The following spring, Causey’s hitting fell even more profoundly, resulting in a mid-July trade to California. And then only nine days later, the Angels sold him to Atlanta, reuniting him with Paul Richards, his first general manager who was now running the baseball side for the Braves.

The 31-year-old Causey no longer possessed the talent that he had shown as a young bonus baby in Baltimore.

In 37 at-bats for the Braves, Causey picked up a mere four hits. Though he finished out the season in Atlanta, he was soon given his unconditional release by Richards. No other teams showed interest in Causey, resulting in his decision to retire.

Though his career as a player had ended, Causey remained connected to the game, first as a ticket manager with the Kansas City Royals and later as the team’s southeast scouting supervisor. By the mid-1970s, he decided to leave baseball completely, taking a job with a major glass manufacturer and eventually becoming a plant manager. Causey now lives in retirement in his native Louisiana.

All these years later, Causey could be excused for looking back with regret at the circumstances that hurt his career. He was clearly never the same player after separating his shoulder. And there’s little doubt that the bonus rule curbed his development. With regard to the bonus rule that played havoc with the beginning of his career, Causey harbored no second thoughts about signing with the Orioles out of high school.

“Oh yeah!” he told Sports Collectors Digest in 1992. “If I had to do it over again, I’d do the same thing.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum