- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Ivie

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Ivie

Just as certain players are emblematic of an era, so too are some cards that make us think of a time that has come and gone. And on occasion, we find that both the player and his corresponding card take us back to a particular time in our game’s history.

Mike Ivie and his 1979 Topps card fall into both of those categories.

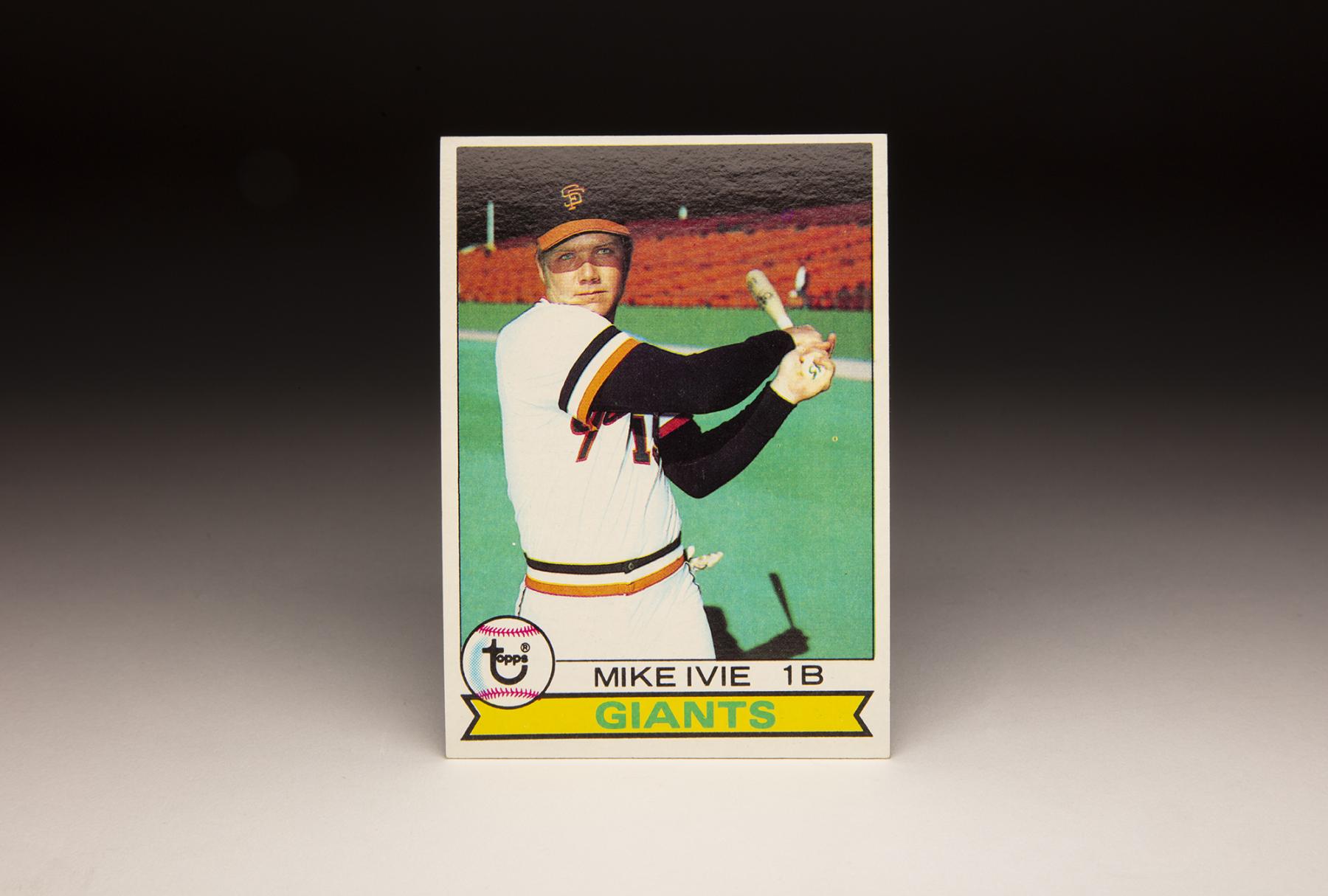

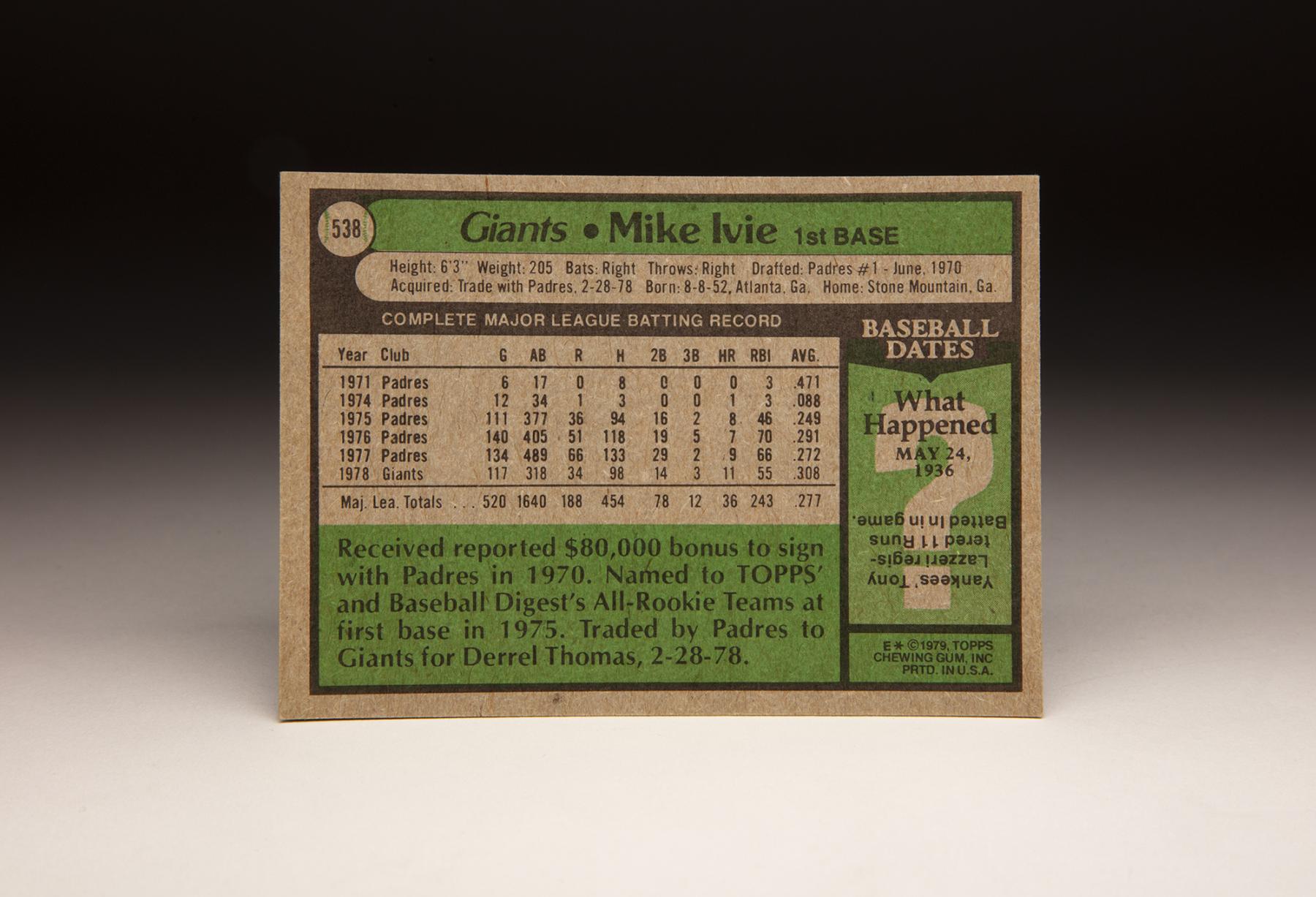

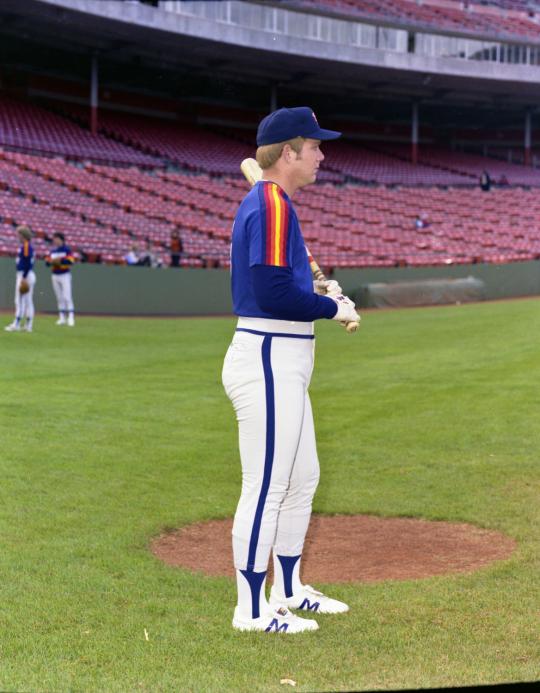

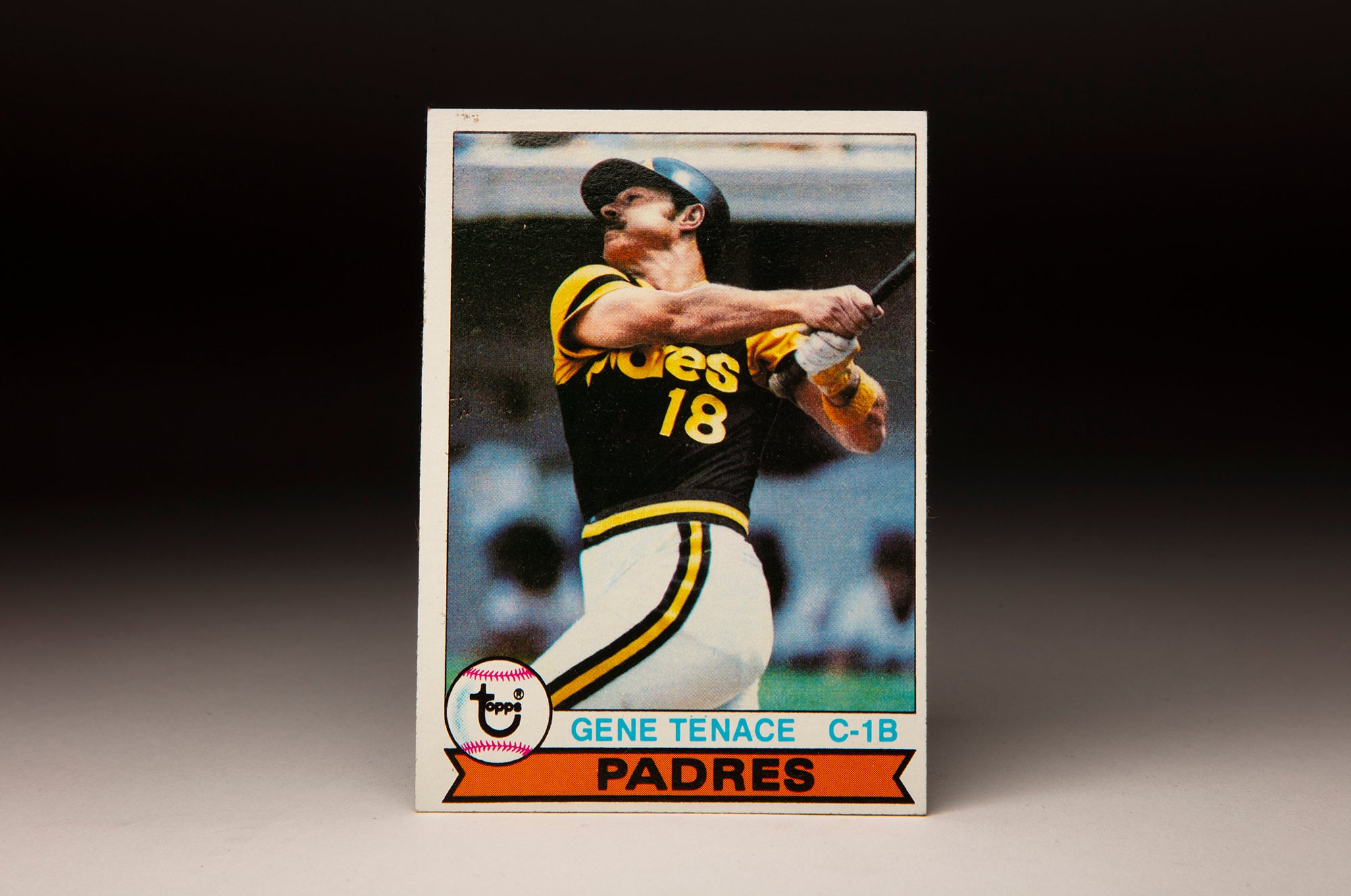

Let’s begin with the card, in this case a selection from the 1979 Topps set. Ivie is seen wearing the San Francisco Giants uniform of the late 1970s: The black, white and orange bands on the sleeves and at the waistline, the Giants’ team name spelled out in black with orange trim and the two-toned cap.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The card also gives us a good look at the backdrop of Candlestick Park. It was during the 1970s that the Giants switched from natural grass to artificial turf, the latter in full evidence behind Ivie. And then there are those brightly colored orange seats, which help to distinguish Candlestick from so many of the cookie-cutter stadiums that came into prominence during the 1970s.

In a way, it seems appropriate that Ivie is spotted on his 1979 card without a smile. In contrast to some of the recent cards we’ve profiled, Ivie’s expression is serious. For Ivie, the game was never easy or carefree. At times, he felt so unhappy that he opted for retirement – only to change his mind within a matter of days or weeks.

As with the circumstances of the card, Ivie himself helps bring us back to the time period. He is a player who has become somewhat forgotten by time, rarely mentioned by fans in today’s game, but a player well remembered by fans who experienced the 1970s. His story is one that involved the mental approach to the game. In fact, fans of a certain age will remember that Ivie struggled with mental health for much of his time in professional baseball, almost ending a career that once seemed so promising.

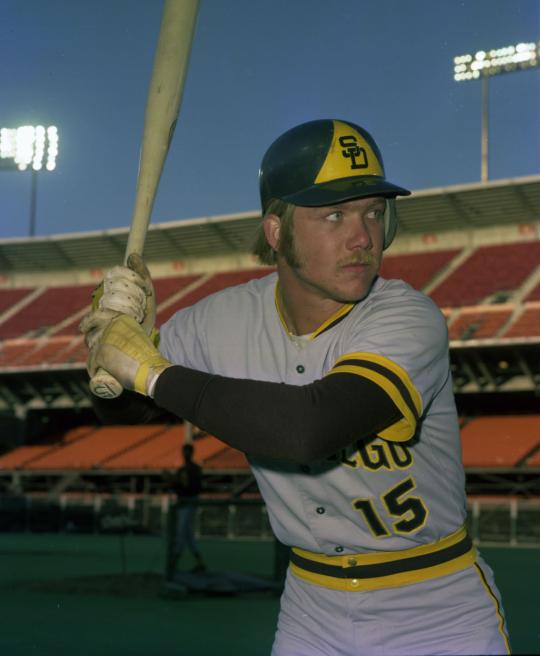

Ivie arrived in pro ball in 1970 when the San Diego Padres made him the first pick in the June draft out of Walker High School in Atlanta and rewarded him with a bonus of $100,000. That draft could well have been called the “draft of the catcher,” given that three catchers were selected within the first four picks. After Ivie, the Montreal Expos took Barry Foote with the No. 3 pick, followed by the Milwaukee Brewers’ selection of Darrell Porter at No. 4. Of the three, Porter would go on to have the best career, but it was the power-hitting Ivie who was considered the best amateur catcher in the land in 1970.

In retrospect, Ivie believed that his status as the No. 1 choice damaged his career. “Being the first pick in the baseball draft might have been the worst thing that happened to me,” Ivie said many years later in an interview with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “At the time, I was so excited, but it turned out to be a curse.” That’s because Ivie felt enormous pressure to live up the lofty billing. His mental state did not come close to matching his physical tools. At 6-foot-4 and 215 pounds, Ivie already had the chiseled physique of a major league player, but he was still only 17 years old. Feeling nervous, he reported to Tri- City of the Northwest League, where he put up mediocre numbers, including a .258 average and only three home runs in 227 plate appearances. The following summer, he played much better, hitting .305 with 15 home runs for Lodi of the Class-A California League.

Once the minor league season ended, the Padres made a curious move, promoting their 18-year-old catching prospect to the major league roster in September. It seemed like a case of rushing a player who was still a teenager, and one who felt the pressure more than most players. Remarkably, Ivie did not seem overmatched in his major league premiere. In fact, he batted .471 in 17 late-season at-bats for the Padres. Ivie looked so good in September of ’71 that the Padres gave him a chance to make the team in the spring of 1972. Then came a surprise. In the middle of Spring Training, Ivie announced that he was going home and did not want to play anymore. Padres executives placed an immediate call to his house, finally convincing him to return to the team. But when Ivie returned, he informed manager Don Zimmer that he no longer wanted to catch, and would only play first base. That created a problem for the Padres, who already had a productive slugger in Nate Colbert playing the position.

Zimmer told the media that Ivie’s refusal to catch would likely cost him a place on the team. “If he’d agree to catch, he’d be up in the big leagues tomorrow,” Zimmer told Bob Hertzel of the San Diego Enquirer. While Ivie had struggled with the demands of catching in 1971, allowing 18 passed balls and at times showing a lack of concentration, the Padres remained convinced that he was capable of handling the position adequately. Unable to persuade Ivie to continue catching, the Padres felt they had no choice but to send him back to the minor leagues. Reluctantly, the Padres gave in to Ivie’s wishes and moved him to first base, the position that he would play for Alexandria of the Double-A Texas League. There he hit 24 home runs, slugged .501 and posted an impressive OPS of .872.

Given such numbers, the Padres felt that Ivie was ready to move up to Triple-A in 1973. Promoted to Hawaii of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, he batted a respectable .270, but injuries limited him to five home runs in just 51 games.

Concerned that Ivie had taken a step back, the Padres took a cautious route and sent him back to Double-A to start the 1974 season. He played well for Alexandria, hitting .292 with 18 home runs. The Padres also experimented with him at other positions, using him at third base and in the outfield, in addition to first base. In September, the Padres brought him back to San Diego and used him as a first baseman in 12 games. In contrast to his 1971 cameo, Ivie struggled for the Padres. He picked up only three hits in 34 at-bats, accounting for an unsightly batting average of .088.

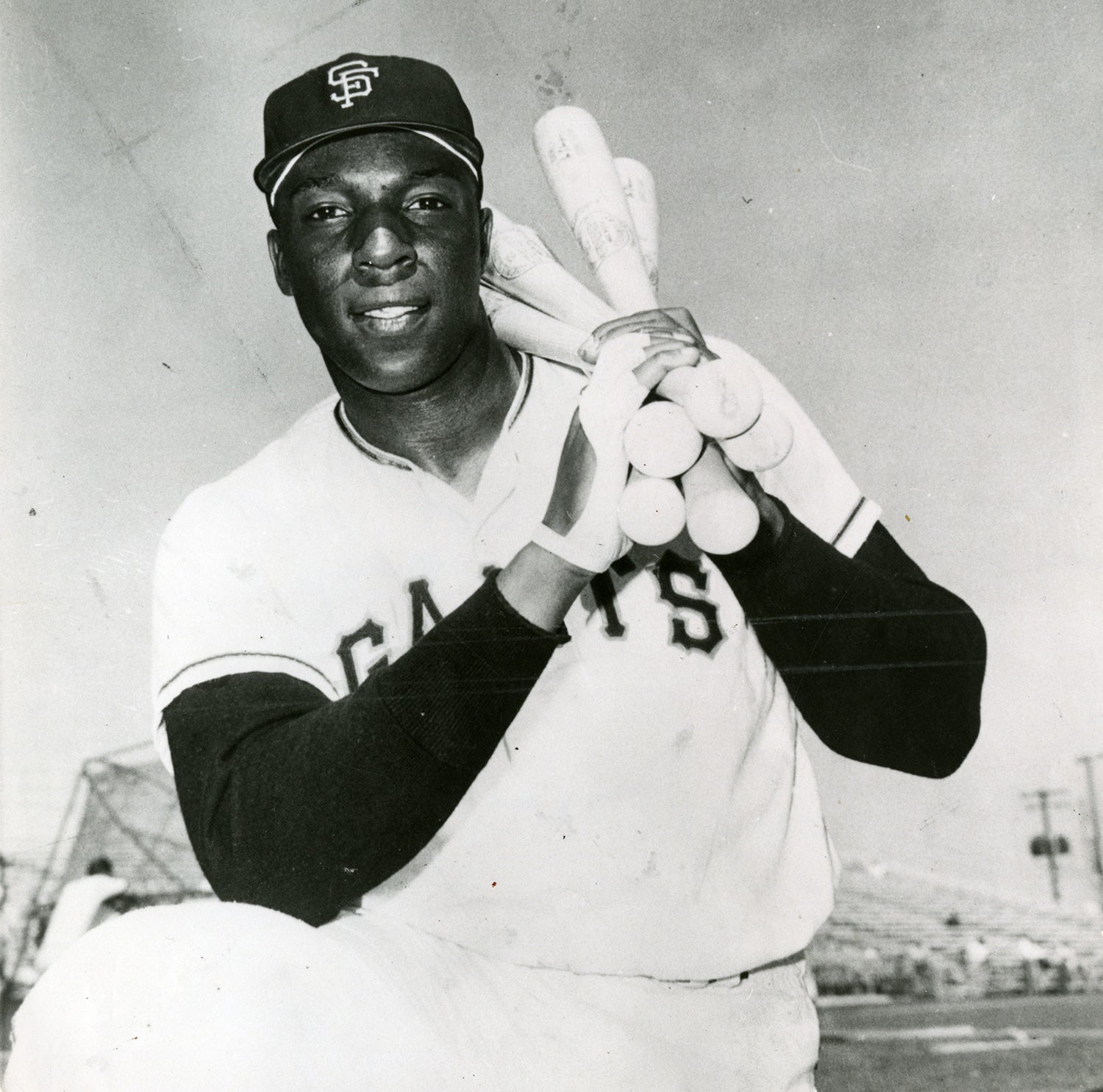

Even though Ivie appeared overmatched against National League pitching, the Padres included him on their Opening Day roster in 1975. With first base now occupied by Willie McCovey, the Padres decided to use Ivie as their regular third baseman. Based on his minor league performance, along with the incredible batting practice displays he put on before games, the Padres had every reason to believe that Ivie would join McCovey and Dave Winfield in forming a lethal middle-of-the-order combination.

That plan never came to fruition. Playing at a position where he lacked athleticism, the rookie third baseman put up less-than-average numbers, including a .249 batting average and eight home runs. Yet, the Padres had no reason to give up on Ivie. In 1976, the Padres moved him back to first base, where he replaced the aging McCovey. Ivie showed improvement as a hitter, batting .291 with an OPS of .756.

That season, the Padres also dabbled with Ivie as a catcher, the position that he had previously refused to play. Near disastrous results ensued for Ivie behind the plate. In two games, he committed two throwing errors. He also had trouble with the basic task of tossing the ball back to the pitcher. In one game, Ivie attempted to return a throw to the pitcher but the ball sailed toward left field, bouncing several times before being picked up the startled Padres’ outfielder, who thought the ball had actually been put into play. It was a problem that would later affect players like Dale Murphy and Mackey Sasser.

As a result of the “mental block,” as some called it, Ivie would never again catch a major league game after the ’76 season. In 1977, Ivie hit .272, but his continued lack of power remained a puzzle to the Padres. He also became embroiled in controversy. On May 2, Padres manager John McNamara penciled in Ivie to play third base. Ivie refused to play the position that day, resulting in a one-game suspension. The next day, a contrite Ivie returned to the team. “I made a mistake,” said Ivie, according to the Sporting News. Ivie spoke to his teammates directly and apologized for his refusal to play. That controversy, coupled with Ivie’s inability to hit home runs, left the Padres pondering what to do with him that winter.

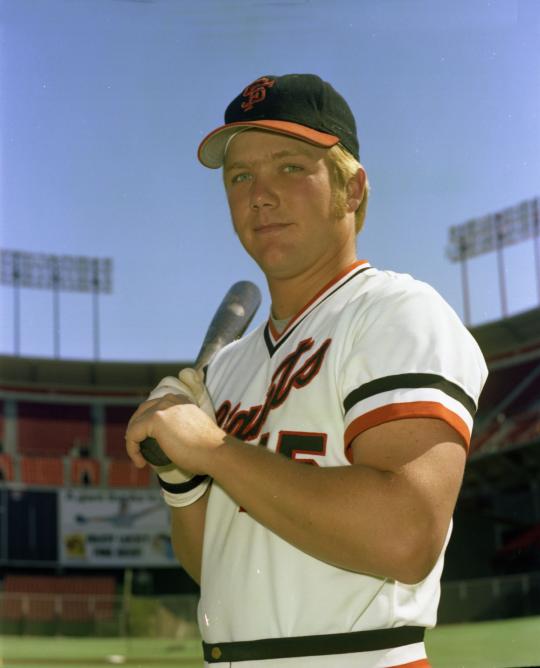

Ivie was still only 25, but his development had clearly stalled. Waiting until February, the Padres finally made a decision on Ivie. They traded him to the Giants for utility infielder Derrell Thomas. The Giants didn’t have a regular position for Ivie, but they platooned him at first base with McCovey, who was now back in San Francisco, while also using him left field. Ivie did well for his new team, hitting .308 while reaching double figures in home runs for the first time (with 11). It seemed that the change of scenery had benefited the young slugger. In 1979, Ivie continued to play multiple positions – and he blossomed at the plate. For the first time in his major league career, he hit with legitimate power, blasting 27 home runs, slugging .547 and posting an OPS of .906. Ivie didn’t see it coming. “I surprised myself,” Ivie told the Sporting News. “I always figured I’d hit about 15 to 20 home runs a year, so I was a little surprised to be up around 30 and to have so many homers and RBIs for so few times at bat.”

For many players, their age-27 season turns into a career year. But in Ivie’s case, an injury that he suffered over the winter undermined his performance. Ivie cut a tendon in his hand while cleaning a hunting knife, forcing him to undergo surgery and creating pain that lasted into the 1980 regular season. In the middle of the year, Ivie left the team, announcing that he was quitting baseball. Feeling depressed and citing what he termed “mental exhaustion,” Ivie called it a “chore” to go to the ballpark each day.

Ivie did return, largely because of an encouraging phone call from McCovey, but then left the team again in September. In and around all of the walkouts and injury problems, Ivie played in only 78 games, hit a mere four home runs, and batted .246. In almost every way, it was the worst season of his big league career.

Ivie’s decision to leave the team on two occasions left some of his teammates feeling resentful.

Heading into Spring Training in 1981, Ivie figured to compete with Darrell Evans and Enos Cabell for playing time at first base. Evans was one of the few Giants willing to speak on the record about Ivie and his commitment to the team. “Mike has got to prove himself,” Evans told Nick Peters, corresponding for the Sporting News. “Enos and I have proven we can play 160 games, Mike hasn’t.” When the Giants broke camp, Evans found himself at third base and Cabell at first base, leaving Ivie as the odd man out. He appeared in only seven games during the month of April, and though he hit well, the Giants did not envision him as a bench player. On April 20, the Giants worked out a trade, sending Ivie to the Houston Astros for fellow first baseman Dave Bergman and outfielder Jeff Leonard. Initially, the Astros hoped that Ivie could play first base and give them a much-needed power bat for their singles-hitting lineup. But Ivie didn’t hit well, and the Astros decided to move Cesar Cedeno from the outfield to first base. Then came the strike, which wiped out the second half of June, all of July, and the early part of August. When the Astros resumed their season on Aug. 10, Cedeno was still at first base, while Ivie remained on the bench. Ivie appeared in only 19 games for the Astros that summer. The following season, he played in only seven games before being released. The Detroit Tigers signed him as a free agent, giving him a chance to play as a part-time DH. Ivie hit 14 home runs in 259 at-bats, but slumped at the beginning of the 1983 season, prompting his release. Only 30 years old, Ivie’s once-promising career had come to an end. Not surprisingly, Ivie left baseball completely. He simply returned home, to hunt and fish, and to work outside of the game. Given his frequent departures from baseball, no one would have been surprised if Ivie had left the game completely. But in the 1990s, he became a youth coach, good enough to lead two teams to Pee Wee Reese League titles in 1997 and ’98. In 2000, Ivie told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that he wanted to return to Organized Ball. “I miss the game a lot. I really want to get back into it. I’d love to be a coach in the minors or a hitting instructor. I want to help someone work through the things that I couldn’t… Baseball is such a hard game.” Ivie has not received that chance to work in the major or minor leagues, perhaps because too much time has passed since his playing days. But it’s clear that he has reconciled himself with the game. And it’s also clear that he’s done well in teaching kids about baseball, how to deal with failure, and how tough the game can be. If Mike Ivie can help youngsters avoid the pitfalls that hurt his own career, he will be very happy about that.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum