- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Gene Tenace

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Gene Tenace

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

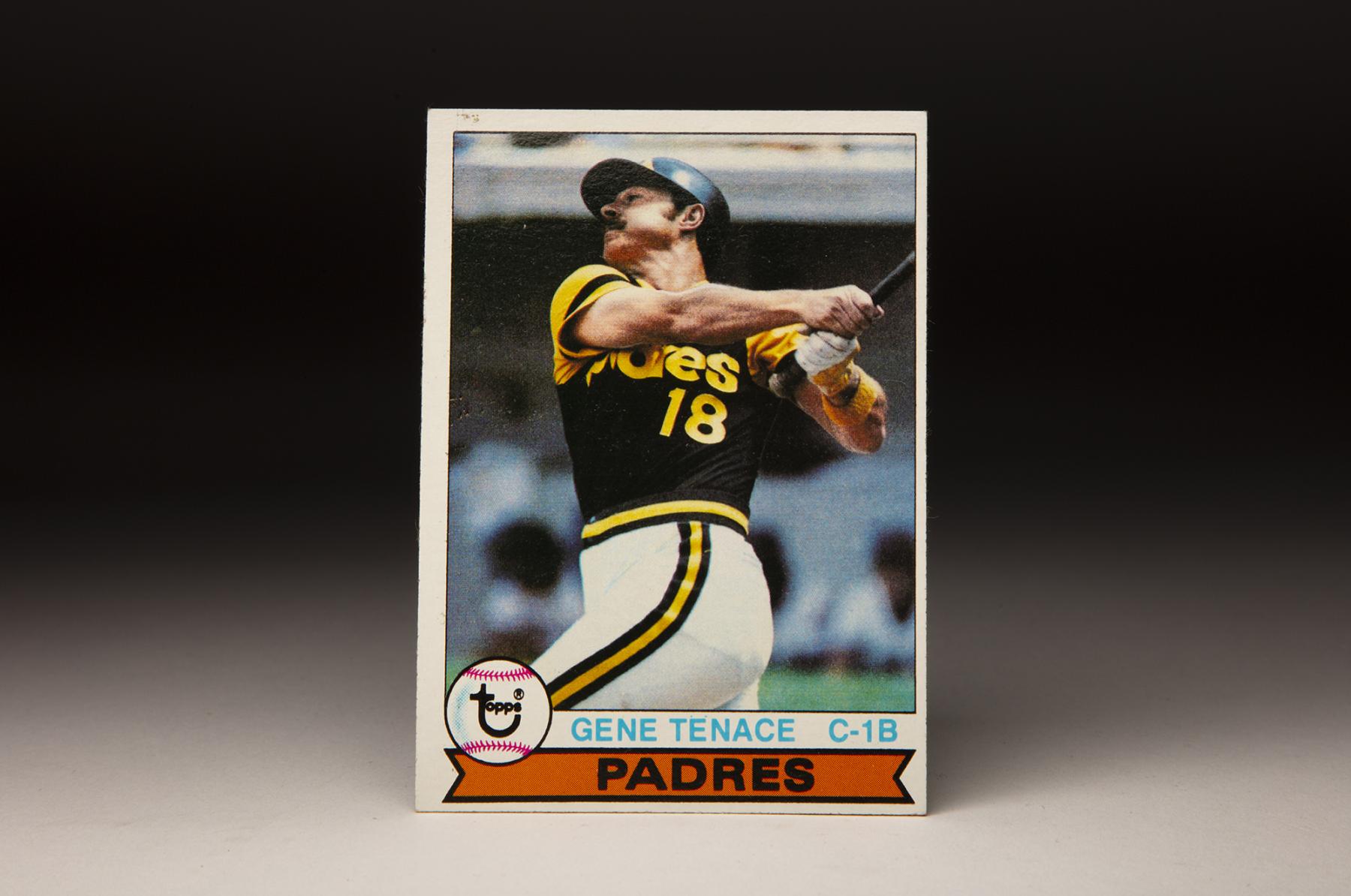

One of the strengths of 1979 Topps is the quality of the action shots. In the early 1970s, Topps tended to include action shots taken from long distances, often featuring multiple players on the same card. While those cards were fun, they didn’t always give us a good look at the player in question.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

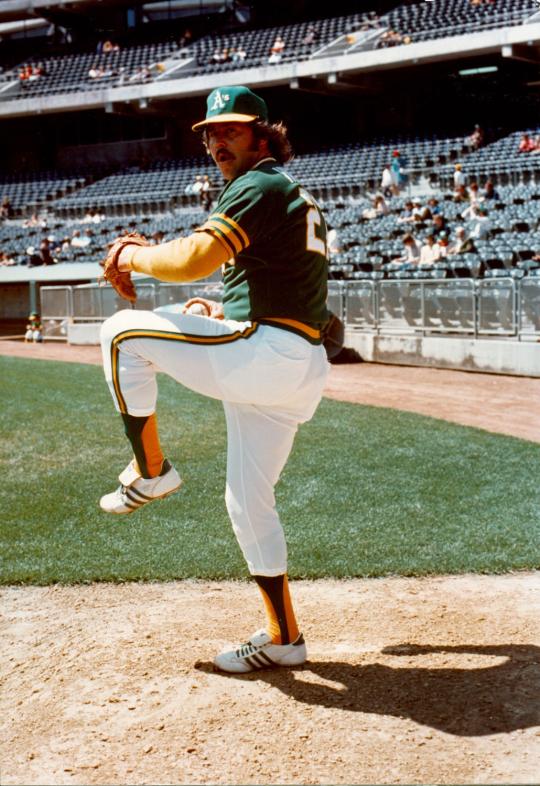

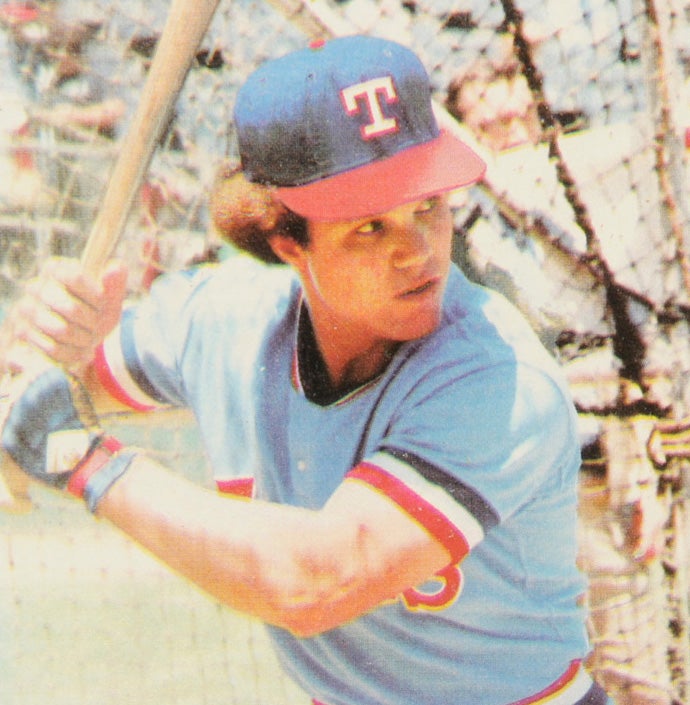

By 1979, Topps photographers had refined their work. A perfect example can be found in this well-focused action shot of Gene Tenace. In a shot taken at Shea Stadium, we are able to see Tenace up close, including the tension and movement of the muscles on his right arm just after he makes contact with the pitch.

Also in evidence are Tenace’s left hand and arm, which are sporting a batting glove and a thick yellow sweatband. And of course, we have a nice close-up view of those garish San Diego Padres uniforms, with their brown tops, yellow lettering and multi-colored racing stripes.

Tenace’s rock-solid physique is fully evident here, too. Listed at six feet and 190 pounds, Tenace appears to have relatively little body fat and plenty of muscle. In an era before weightlifting became common, Tenace stood out for his Gibraltar-like stature.

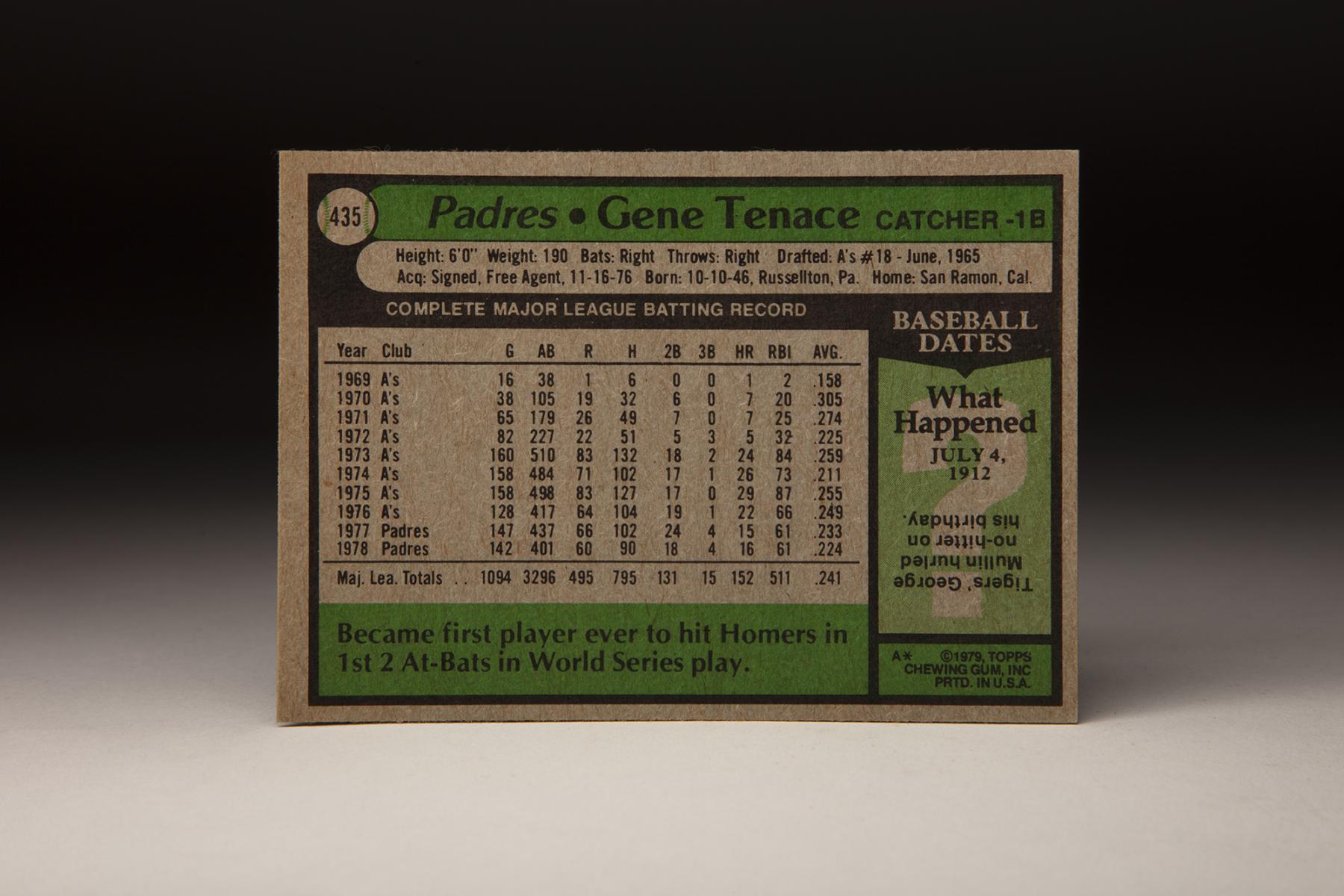

By 1979, Tenace was well-established as one of the game’s premier hitting catchers. A decade and a half earlier, he was still living in the small Midwestern town of Lucasville, Ohio, where he grew up. His grandparents had emigrated from Italy and had decided to Americanize their last name, changing it from its original “Tennaci.”

Tenace’s grandfather gave the youngster the nickname, “Steamboat.” It was a reference to the unusually clumsy way that Tenace walked – sort of like a steamboat carrying a load of heavy cargo on a river.

Tenace might have walked awkwardly, but he could play the game well at a young age. His father, a former semi-pro player, drove him hard to improve his baseball skills. Tenace felt so much pressure to excel that he developed an ulcer at the age of 13. The unexpected health problem forced him to miss an entire season, and when he did return, he asked his father not to attend any more games. Tenace emerged as an all-state shortstop. He also starred in American Legion ball, where his teammates included future major leaguers Al Oliver and Larry Hisle.

Prior to the 1965 draft, the Kansas City Athletics scouted Tenace and liked him enough to select him in the 20th round, an indication that they regarded him as a prospect, but only a fringe one. Realizing that he was not suited to play shortstop, the A’s quickly switched Tenace to the outfield. In one minor league game for Peninsula of the Carolina League, Tenace showed his versatility by playing all nine positions in a game – a promotional stunt meant to attract more fans to the ballpark.

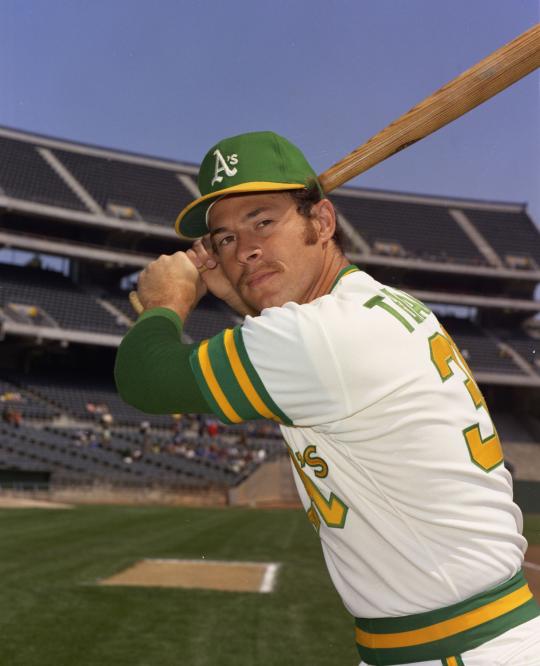

As an outfielder, Tenace faced an overload in the A’s system. In 1968, the A’s already boasted of an outfield that included Joe Rudi, Rick Monday and Reggie Jackson. Believing that he had little chance of cracking that outfield, Tenace thought about quitting.

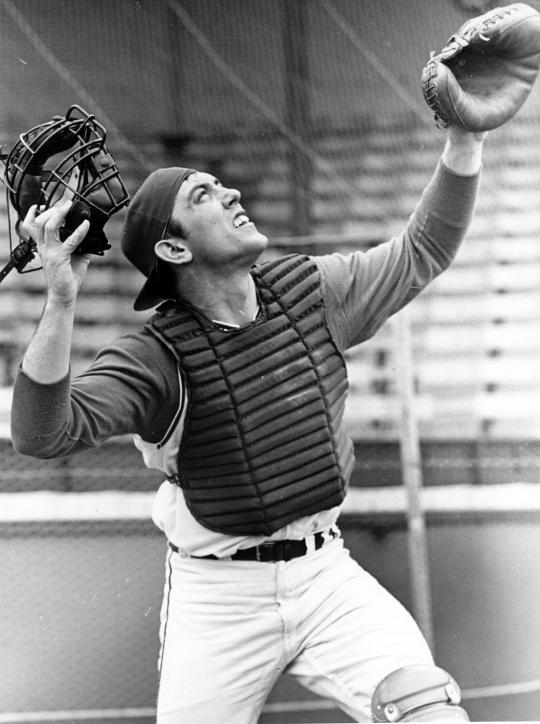

The A’s, by now relocated to Oakland, responded to the logjam by converting Tenace to catcher. The A’s felt confident that Tenace could make the adjustment to a radically different position, one of the thinnest throughout the Oakland system. In 1969, Tenace moved up to Double-A Birmingham, where he worked under the tutelage of manager Gus Niarhos, a former big league catcher.

Known for his skill in developing young catchers, Niarhos compared Tenace to his former teammate with the New York Yankees, Yogi Berra. (Like Tenace, Berra made the transition from outfield to catcher.) Tenace impressed Niarhos with his strong throwing arm, but struggled in other phases of defensive play.

“The biggest thing is getting him to relax,” Niarhos told the Sporting News. “When he does, and if he keeps hitting, he’ll be up there [in Oakland]. That could be next year; that’s how much I think of his chances.”

In particular, Niarhos liked Tenace’s natural curiosity and willingness to learn. “Tenace wants to know. He asks, too. He’s a good student.”

Tenace so excelled as a disciple of Niarhos that he actually beat his manager’s timetable of making the major leagues by one full season. The A’s called him up in May of 1969, giving him a 16-game cameo. Tenace was overmatched – he batted only .158 – but by 1970, he made it to Oakland to stay.

He appeared in only 38 games, but batted .305 and compiled a .430 on-base percentage. Tenace hit so well that he took over the No. 1 catching job from Dave Duncan and Frank Fernandez in September.

In 1971, Tenace shared catching duties with Duncan, who was considered the best receiver on the Oakland roster. When given a chance to play, Tenace hit well, batting .274 with seven home runs in 65 games.

Then came an unexpected slump in 1972. Tenace saw his batting average fall to .225 and his home run output tumble to five. He caught only 49 games, while also being used as a jack-of-all-trades, appearing in games at first, second and third base and in the outfield.

It was also during the 1972 season that Tenace was forced to play second base as part of owner/general manager Charlie Finley’s revolving door plan at the position. Finley instructed manager Dick Williams to pinch-hit for his second base at every turn, resulting in the use of three or four second basemen a game.

On occasion, Tenace was used as part of that rotation, even though he had little experience or comfort level playing the pivot.

After the revolving door experiment at second base came to a close, Williams decided to make a change at catcher. He benched Duncan and made Tenace his regular catcher, hoping that the latter would give him more offense down the stretch and into the postseason.

Playing against the Detroit Tigers in the ALCS, Tenace batted a mere .059, picking up one hit in 17 at-bats.

Then everything changed in the 1972 World Series. Participating in his first Fall Classic, Tenace blasted two home runs in his first two at-bats. For the Series, he tormented the Cincinnati Reds with four home runs and a .348 batting average and a 1.313 OPS, a performance that earned him Series MVP honors, as the A’s took home their first world championship since their days in Philadelphia.

As well as Tenace played against the Cincinnati Reds, the Series did not come easily.

The Reds ran at will against Tenace’s throwing arm, making him a liability as a catcher.

And then came a threat to Tenace’s life.

During Game 6, police arrested a 32-year-old Louisville, Ky., man, in possession of a loaded gun and a bottle of whiskey, who had made the verbal threat.

Although the threat had clearly shaken him, Tenace had no plans to sit out Game 7.

“It scares me, but I’ll play tomorrow,” Tenace told the Associated Press. “I’m a little scared, but what can I do, tell the manager not to play me?”

Tenace not only played in Game 7, but excelled. He picked up two more hits, including a double, and drove home two of Oakland’s three runs. Tenace’s latest effort sealed the MVP vote and made him a household name, resulting in appearances on late-night talk shows. For a player who had struggled to find consistent playing time during a disappointing regular season, the transformation to national celebrity was a remarkable development.

In 1973, Tenace’s role with the A’s continued to grow. Duncan held out of Spring Training, giving Tenace more playing time behind the plate. But then Finley traded Duncan, sending him to Cleveland for another catcher, Ray Fosse.

With Fosse now the A’s No. 1 backstop, Tenace moved to first base. He caught only 33 games as Fosse’s backup, but he hit well, clubbing 24 home runs and drawing 101 walks, helping the A’s to another divisional title and a return trip to the World Series.

In 1974, Tenace’s batting average fell to .211, but he hit a career-best 26 home runs. He continued to show remarkable discipline with regard to the strike zone, leading the American League with 110 walks.

The A’s won their third consecutive championship, adding to Tenace’s collection of World Series rings.

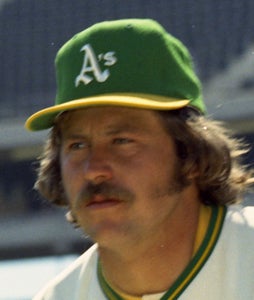

While players like Reggie Jackson, Jim “Catfish” Hunter, Vida Blue, and Rollie Fingers garnered most of the attention, Tenace quietly played a vital role in helping build the Oakland dynasty.

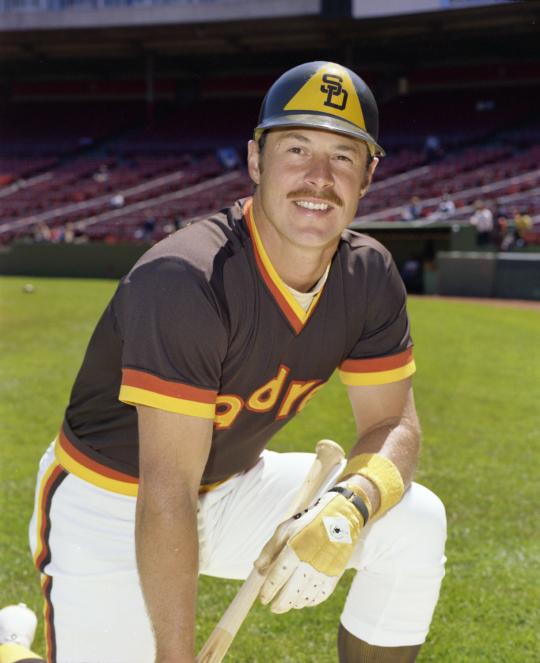

Tenace continued to excel in 1975 and ’76, earning his first All-Star Game nod and picking up some MVP voting consideration. With the end of the ’76 season came free agency, allowing many of the A’s top players, including Tenace, to sign multiyear contracts with other clubs. Tenace and Fingers both signed with the Padres, owned by the free-spending Ray Kroc.

Tenace turned in his gaudy, green-and-gold Oakland polyesters for the even gaudier brown-and-yellow threads preferred of the Padres. Making the transition to the National League, Tenace hit 15 home runs, but his patient hitting style drew the ire of Kroc.

“Tenace kept saying if he played every day he’d improve,” Kroc complained to the Sporting News. “Well he’s been in there every day and he hasn’t done a damn thing. All he wants to do is walk. Well, we can’t win games waiting for walks. He’s being paid to hit, and he can’t hit.”

In reality, Tenace did hit that season, putting up an OPS of .824.

He would follow that up with three more productive seasons in San Diego, but the Padres failed to make the postseason during his time there.

After the 1980 season, the Padres pulled off a gargantuan 11-player deal with the St. Lous Cardinals. As part of the deal, Tenace and Fingers went to the Cardinals for prized young catcher Terry Kennedy.

Since the Cardinals already had Darrell Porter to catch and Keith Hernandez to play first base, they envisioned Tenace as a backup at both positions.

He filled that role capably for two seasons and helped St. Louis win the 1982 World Series before becoming a free agent and signing with the Pittsburgh Pirates, where he struggled in a utility role. The following spring, the Pirates released Tenace, ending his 15-year career.

While Tenace’s playing days had come to a close, his association with baseball did not. He turned to coaching, first in the minor league system of the Boston Red Sox. At one point, rumors circulated that he would replace Chuck Tanner as manager of the Pirates, but that call never came.

Instead, he joined the coaching staff of the Houston Astros, followed by a move to the Toronto Blue Jays. With the Jays, he worked under Cito Gaston during their world championship seasons of 1992 and ’93.

That experience gave Tenace a total of six World Series rings – including four as a player – for his career.

Leaving baseball in 2009, Tenace is now enjoying retirement in Redmond, Ore.

Those six rings stand as a testament to the perseverance of an underrated player who had to deal with a demanding father, several changes in positions, the whims of two volatile owners and even a World Series death threat. Somehow, Gene Tenace overcame all of it to forge a career full of winning.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame