- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bud Harrelson

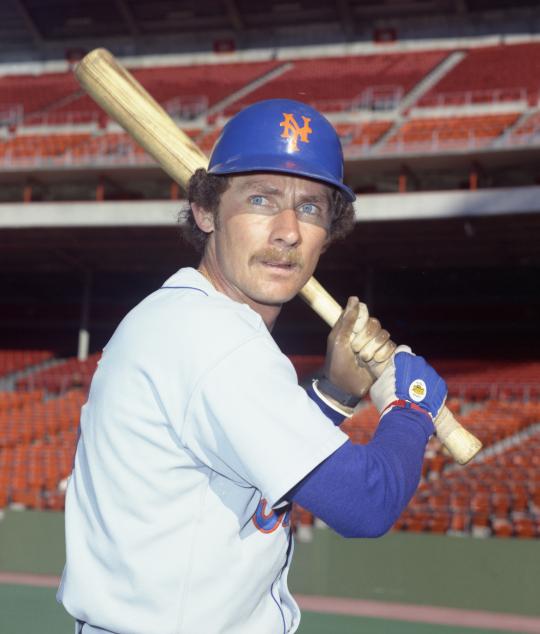

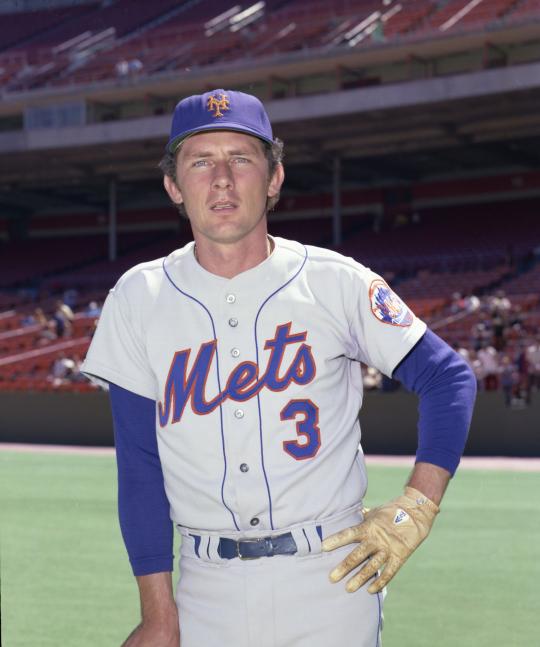

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bud Harrelson

This card has 1970s written all over it.

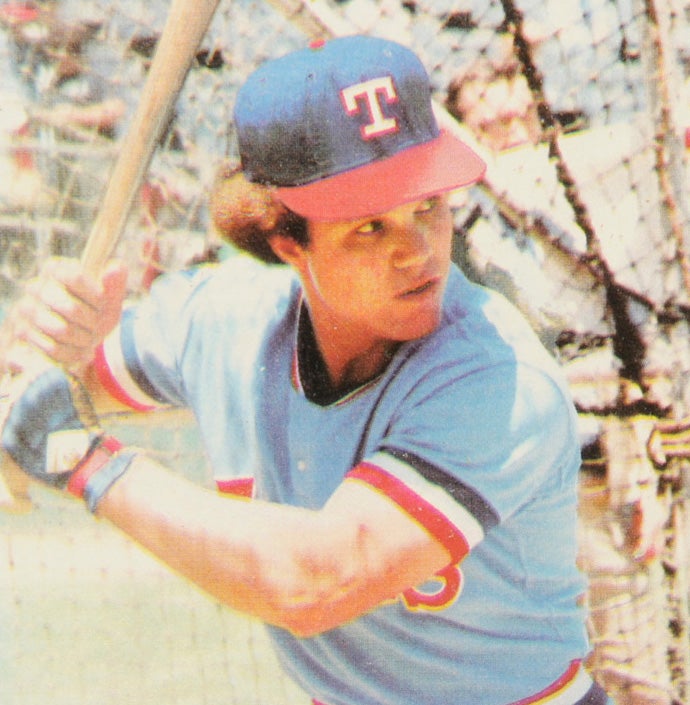

Buddy Harrelson, near the end of a fine career, is wearing large aviator sunglasses, which were starting to become popular among ballplayers in the 1970s.

If we look to the sides of his cap, we can see evidence of his hair being permed, another fashion trend making the rounds at the time.

And then there are the powder blue road uniforms being used by the Philadelphia Phillies. Powder blue was a popular color for road uniforms in the 1970s; not only did the Phillies sport them, but so did the Montreal Expos, St. Louis Cardinals, Kansas City Royals, Milwaukee Brewers, and Texas Rangers, among other teams.

As a player, Harrelson is best remembered for his fielding prowess, but Topps chose to photograph him holding a bat for this picture, taken sometime during the 1978 season. Harrelson is clearly choking up on the bat, a common characteristic for him and other diminutive players of the 1970s who did not hit for much power. We can also see that Harrelson is holding a bat without a knob. I don’t recall knobless bats being especially common in the 1970s, but this kind of bat certainly made sense for a player choking up. After all, if you’re not holding the bat near the end, what is the need for a knob to begin with?

As an offensive player, Harrelson often looked out of place. First of all, he was so smallish in stature that he sometimes took on the profile of a high school player doing battle against professional players. Listed at 5-foot-11 and 165 pounds (though he generally weighed significantly less), he had a tendency to lose weight during the season, a good problem to have if you are built like George “Boomer” Scott, but not when you are nicknamed “Twiggy.”

Yet, Harrelson more than made do. A self-taught switch-hitter, he slapped the ball from both sides of the plate, bunted the ball exceptionally well, stole bases when the situation warranted, and, as a testament to his smartness, took lots of pitches. And on defense, he was exceptional, one of the best shortstops to play the game in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The lack of size didn’t prevent Harrelson from starring in baseball, basketball, and football at the high school level. (In fact, he played scholastic football at all of 97 pounds.) Born Derrel McKinley Harrelson, he earned a basketball scholarship from San Francisco State, where he also played baseball. Some scouts bypassed him completely, dismissing him as too small and fragile to play the game professionally, but his athletic skills drew the attention of several teams, including the Chicago Cubs, New York Yankees, and St. Louis Cardinals. The Yankees offered him the best contract, but Harrelson felt the depth of talent within the organization would make it difficult for him to move up. Instead, he accepted an offer from the expansion New York Mets, coming off an inaugural season in which they won only 40 games.

After signing with the Mets in June of 1963, Harrelson reported to Salinas, the club’s affiliate in the Single-A California League. Originally a right-handed hitter, Harrelson came to bat only 136 times before being hit in the left arm with an errant pitch. The pitch broke his arm and ended his season abruptly.

Harrelson returned to health in 1964. He played a full season for Salinas, batting .231 with three home runs. While his hitting lagged, he exhibited patience in the batter’s box (drawing 64 walks) and speed on the bases (12 stolen bases in 13 attempts). In the field, he showed good range at shortstop, but committed 34 errors, an indication of his need for more reps in the minor leagues.

The Mets liked Harrelson’s athleticism so much that they bumped him all the way up to Triple-A Buffalo in 1965. He improved his batting average to .251 while continuing to play somewhat erratically at shortstop. Despite his statistical shortcomings, the Mets opted to promote him to New York in September. He came to bat 37 times, batting a mere .108.

Understandably, the Mets sent Harrelson back to Triple-A in 1966, this time with their new affiliate at Jacksonville, Fla. It was there that Harrelson decided to try his hand at switch-hitting. His Triple-A manager, Solly Hemus, liked what he saw of Harrelson as a left-handed hitter, where he could also better utilize his skills as a bunter.

Harrelson batted only .221 for Jacksonville, but made strides with his fielding. In August, the Mets called him back up to New York and used him semi-regularly at shortstop, where he committed only one error over the balance of the season.

In 1967, the Mets entered Spring Training with the idea of using veteran Roy McMillan as their shortstop. But then McMillan suffered a major injury to his shoulder. With McMillan sidelined by what would become a career-ending injury, the Mets turned to Harrelson as their Opening Day shortstop. The first month of the season did not go well for Harrelson. He batted under .200 and committed a whopping 21 errors in April, but the Mets remained patient. Working with McMillan on his fielding and with coach Yogi Berra on his hitting, Harrelson settled down and showed major improvement. By June, manager Wes Westrum felt confident enough to make the following remark to Dave Anderson of The New York Times: “At his age [23], we might be able to forget about shortstops for another decade or more.”

From May through September, Harrelson made only 11 errors and slowly raised his batting average into the .250 range. By the end of the season, the Mets felt comfortable with Harrelson playing shortstop every day.

After the promise of 1967, Harrelson fell back in 1968 for a variety of reasons. He missed some playing time because of his obligation to the Military Reserves. He also struggled with torn cartilage in his knee. Harrelson did not hit as well as he had in ’67, but then again, most hitters saw a tail-off in production during the Year of the Pitcher.

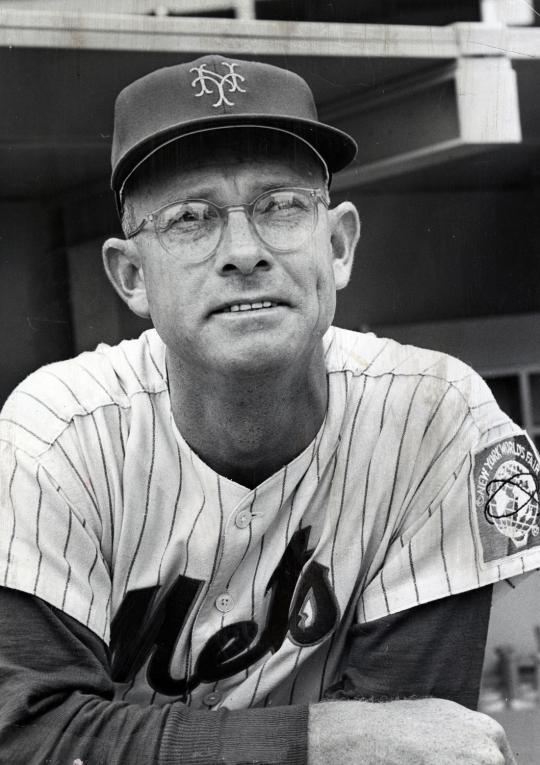

New Mets manager Gil Hodges, who had replaced Westrum prior to the 1968 season, remained confident in Harrelson. As the Mets prepared for Spring Training in 1969, Harrelson went to work. He lifted weights during the winter and put on 10 pounds of muscle. He also quit smoking. Reporting to St. Petersburg stronger and in better condition, Harrelson improved on his 1968 performance.

Given his patient batting eye, Hodges used Harrelson as his No. 2 hitter against right-handed pitching. Harrelson responded by compiling a .341 on-base percentage. In the field, he played an excellent shortstop, cutting down his error total and occasionally making the spectacular play.

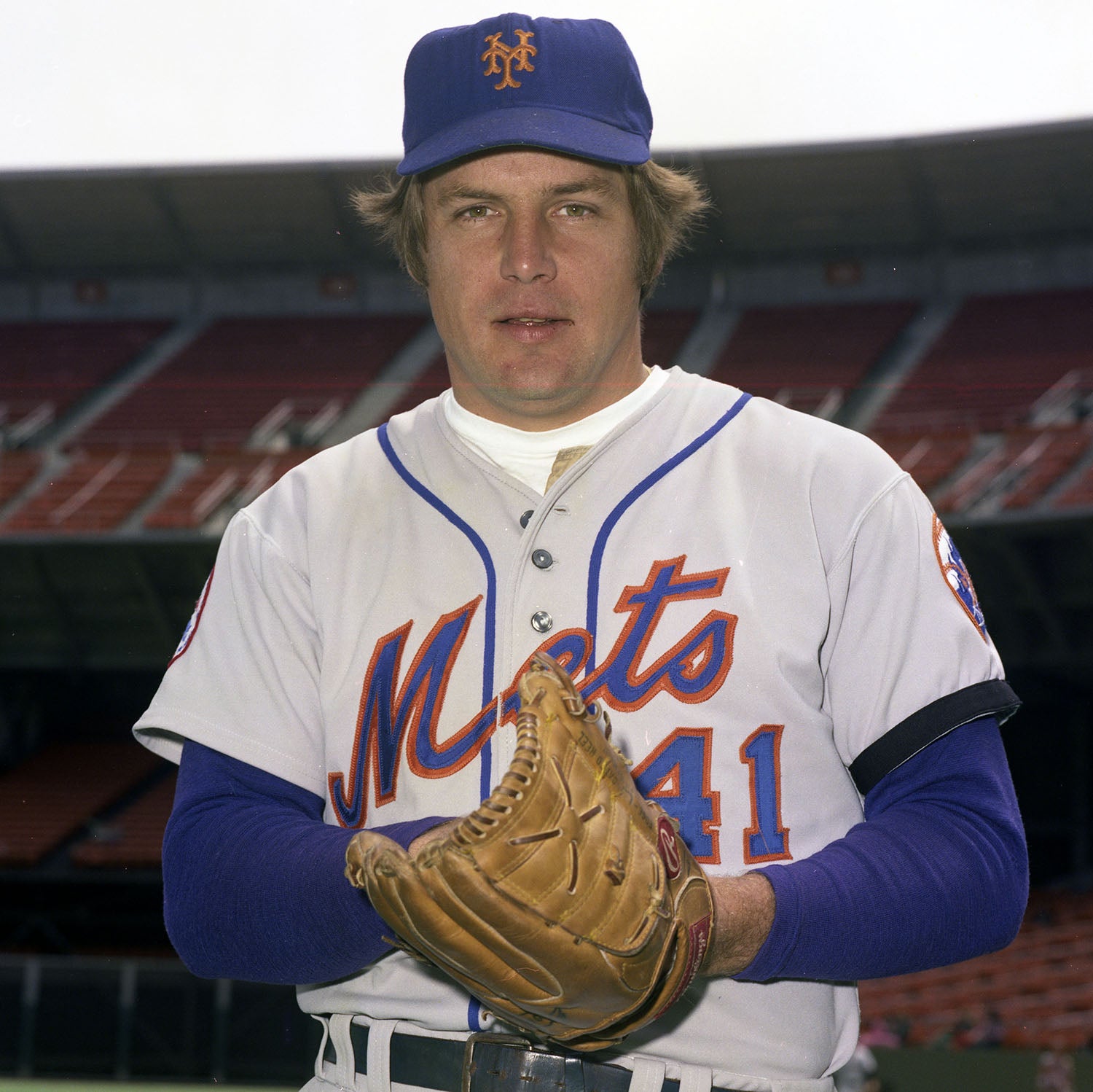

Among the Mets, Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Tommie Agee, and the newly acquired Donn Clendenon received much of the attention for the team’s surprising emergence as a contender. But Harrelson played an important role, too, stabilizing an infield that featured platoons at the other three positions. With Harrelson contributing quietly, the Mets pulled off a remarkable comeback against the Chicago Cubs and won the National League East going away.

In the playoffs and World Series, Harrelson continued to do his part. He drove in three runs in the NLCS, while fielding his position without incident. In the World Series, he made only one error in a game that had already been decided, but was otherwise flawless in the field, helping the Mets to a stunning five-game win over the Baltimore Orioles.

In 1970, Harrelson performed even more capably. Rarely taking a day off, he appeared in 157 games. He drew 95 walks, a remarkable total for a .243 hitter without much power. He also stole 23 bases in 27 attempts. As a reward for his efforts, Harrelson was named to his first All-Star team and also received support in the MVP voting, finishing 20th in the balloting.

Harrelson’s level of performance surprised some observers, especially those who seemed obsessed with his lack of size. While acknowledging his shortstop’s diminutive stature, Harrelson’s manager didn’t seem too concerned.

“He insists he weighs 155 pounds, though it’s probably closer to 135,” Hodges told Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor. “The thing is nobody can catch him on the scales. But whatever the needle says, he’s 200-plus pounds of professional ballplayer.” The 1971 season saw no let-up in Harrelson’s play. He made another All-Star team, placed 22nd in the league’s MVP voting, and picked up the first Gold Glove Award of his career. But then a variety of injuries set Harrelson back in 1972. Forced to miss significant playing time, he appeared in only 115 games and batted .215, his worst mark since his debut of 1965. After a three-year postseason drought, Harrelson and the Mets returned to the NLCS in 1973. That fall, the Mets took on the favored Cincinnati Reds in a series that was marked by controversy. After Jon Matlack shut down the Reds in Game 2, Harrelson delivered a memorable sound bite to a group of reporters.

“[Matlack] made the ‘Big Red Machine’ look like me today,” said Harrelson.

It was a relatively innocuous comment in which Harrelson mostly poked fun at himself, but some of the Reds players took it as an insult.

Among the Reds, Pete Rose was particularly upset about the remark. On a double play grounder in Game 3, Rose decided to use a body-block in taking out Harrelson. During the course of his slide, Rose also elbowed Harrelson, who considered that a cheap shot and said something to the Reds’ star. Rose then grabbed Harrelson and pinned him to the ground, but the shortstop did not back down. He and Rose wrestled each other for a few moments, with the undersized Harrelson conceding about 30 pounds. The brush-up initiated a bench-clearing brawl.

The incident left Harrelson with a minor bruise above his eye, and a fine of $250 from the league office, but more importantly, it gained him favor with Mets fans. They admired his willingness to go toe to toe against a larger man.

The Mets won the game that day, setting the stage for an unexpected Championship Series victory over the heavy-hitting Reds. In a seven-game World Series against the Oakland A’s, Harrelson compiled a .379 on-base percentage, but the Mets fell just short of another stunning upset in the postseason.

Over the next four years, a cascade of injuries prevented Harrelson from playing in any more than 118 games in a single season. With his body breaking down, Harrelson’s hitting also suffered, to the point that he fell to a .178 batting average in 1977. When the Mets brought Tim Foli back to play shortstop in 1978, Harrelson became a glorified backup. He approached general manager Joe McDonald, asking for a trade. During the latter days of Spring Training, the Mets fulfilled his wish, trading Harrelson to the divisional rival Phillies for young second baseman Fred Andrews.

Playing capably in a new role as utilityman, Harrelson hit .214 to help the Phillies win their third straight National League East title in 1978. In 1979, Harrelson hit .282, compiled a .395 on-base percentage, and filled in at shortstop, second base, third base, and even the outfield.

He then became eligible for free agency after the ‘79 season and signed with the Texas Rangers, where he started 77 games at shortstop and batted a respectable .277. Harrelson seemed to have enough ability left to return for another season, but at 36, he opted for retirement.

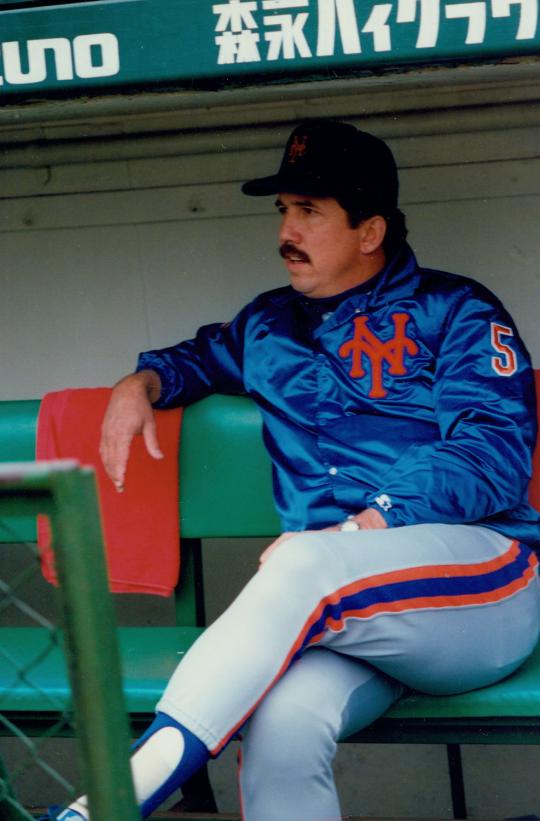

Harrelson did not remain out of baseball for long. In 1981, he returned to the Mets’ organization as their first base coach, spent the next year broadcasting for the Mets, and then became a manager in the club’s farm system.

In 1985, the Mets asked him to rejoin the big league staff, this time as third base coach, replacing Bobby Valentine, who had been hired as manager by the Rangers.

Now working for manager Davey Johnson, Harrelson’s timing could not have been better. He rejoined the coaching staff just as the Mets became a viable contender in the National League East. The following season, the Mets won the World Series under Johnson; Harrelson stood as the only holdover from the 1969 team who remained in uniform for the ’86 championship. For his efforts as a coach, Harrelson took home his second World Series ring.

In 1990, the Mets made a managerial change, firing Johnson and calling on Harrelson as his replacement. The Mets initially performed well for Harrelson, making a run at the NL East title before falling just short to Pittsburgh.

As a manager, Harrelson tried to pattern himself after Gil Hodges, his manager in New York. But the 1991 season proved difficult. He decided to pull himself from a regular spot on the Mets’ pregame show on WFAN Radio because of what he perceived as an overly negative tone to the show. He also decided to back away from an effort to resolve a feud between one of his players, Vince Coleman, and third base coach Mike Cubbage.

Harrelson received criticism for some of his strategic decisions and also heard a familiar knock: That he was simply too nice of a guy to be a successful manager. At one point in early July, the Mets won 10 straight games, but that was soon followed by a second half fade.

During the final week of the disappointing season, the Mets fired Harrelson and replaced him with Cubbage.

As a manager, Harrelson forged a winning percentage of .529, but admitted that his lack of experience had hurt him.

Harrelson left baseball for a spell, but returned to the game in the late 1990s, albeit in the form of independent minor league ball.

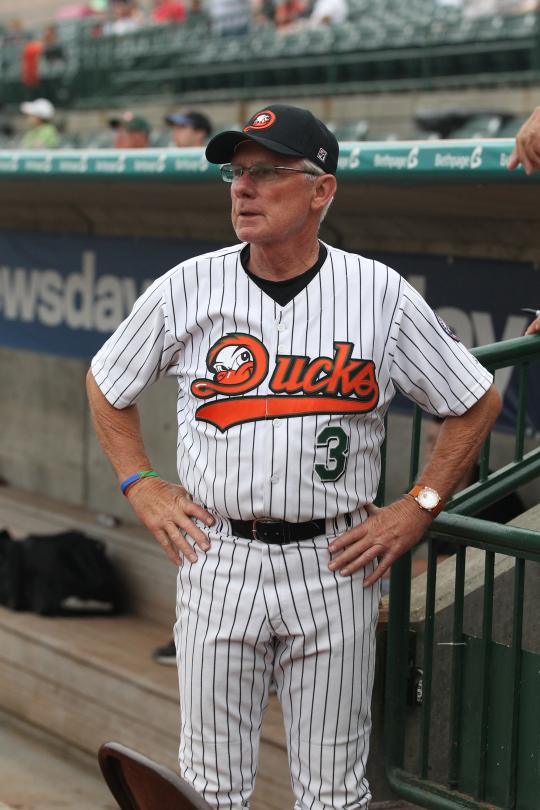

Harrelson assumed partial ownership of the Atlantic League's Long Island Ducks, while also serving as the team’s manager and vice president of baseball operations.

Harrelson passed away on Jan. 10, 2024, at age 79 after a lengthy battle with Alzheimer's disease.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame