- Home

- Our Stories

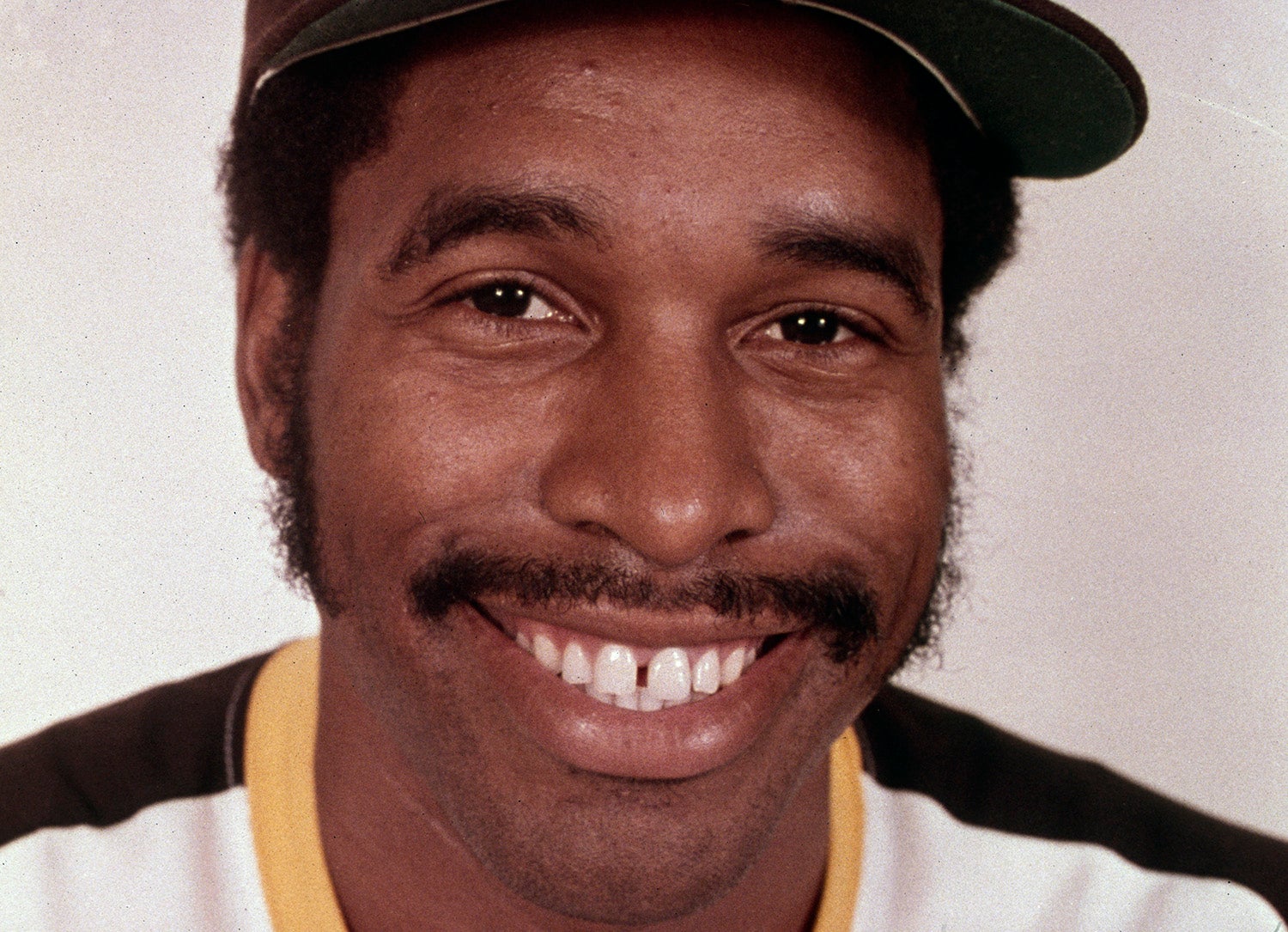

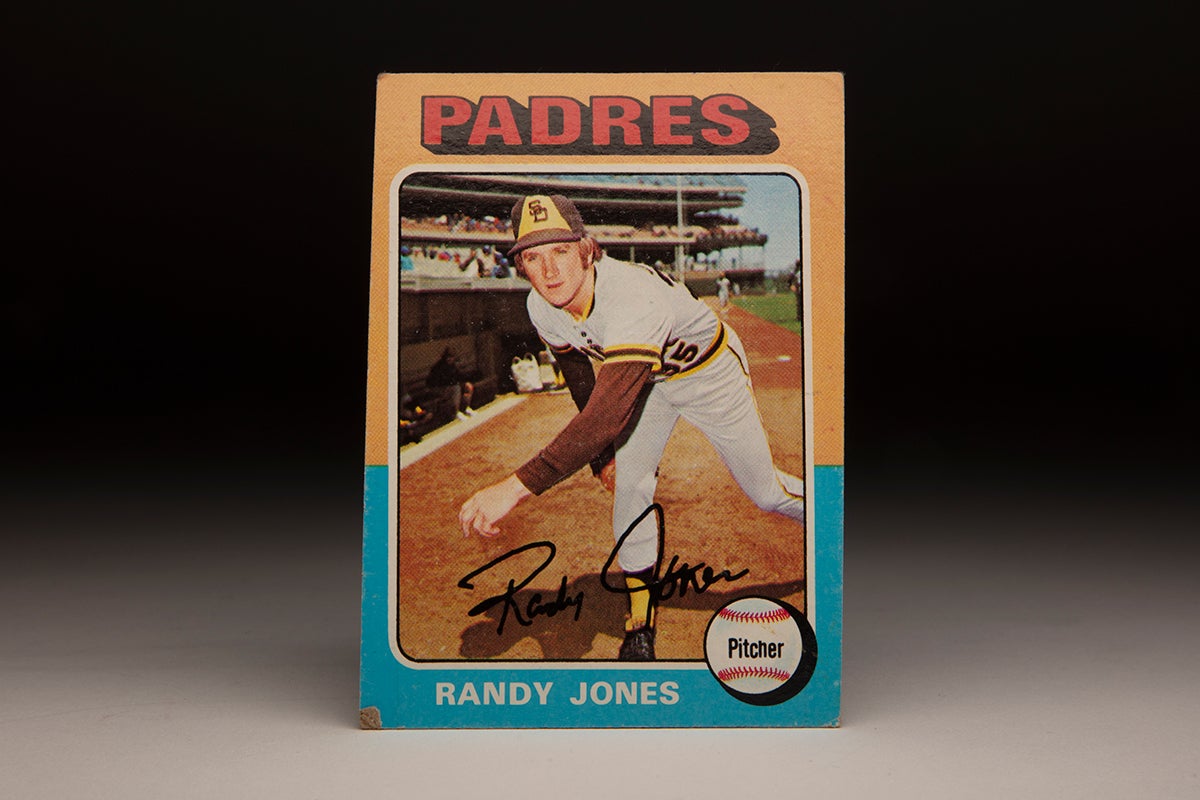

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Randy Jones

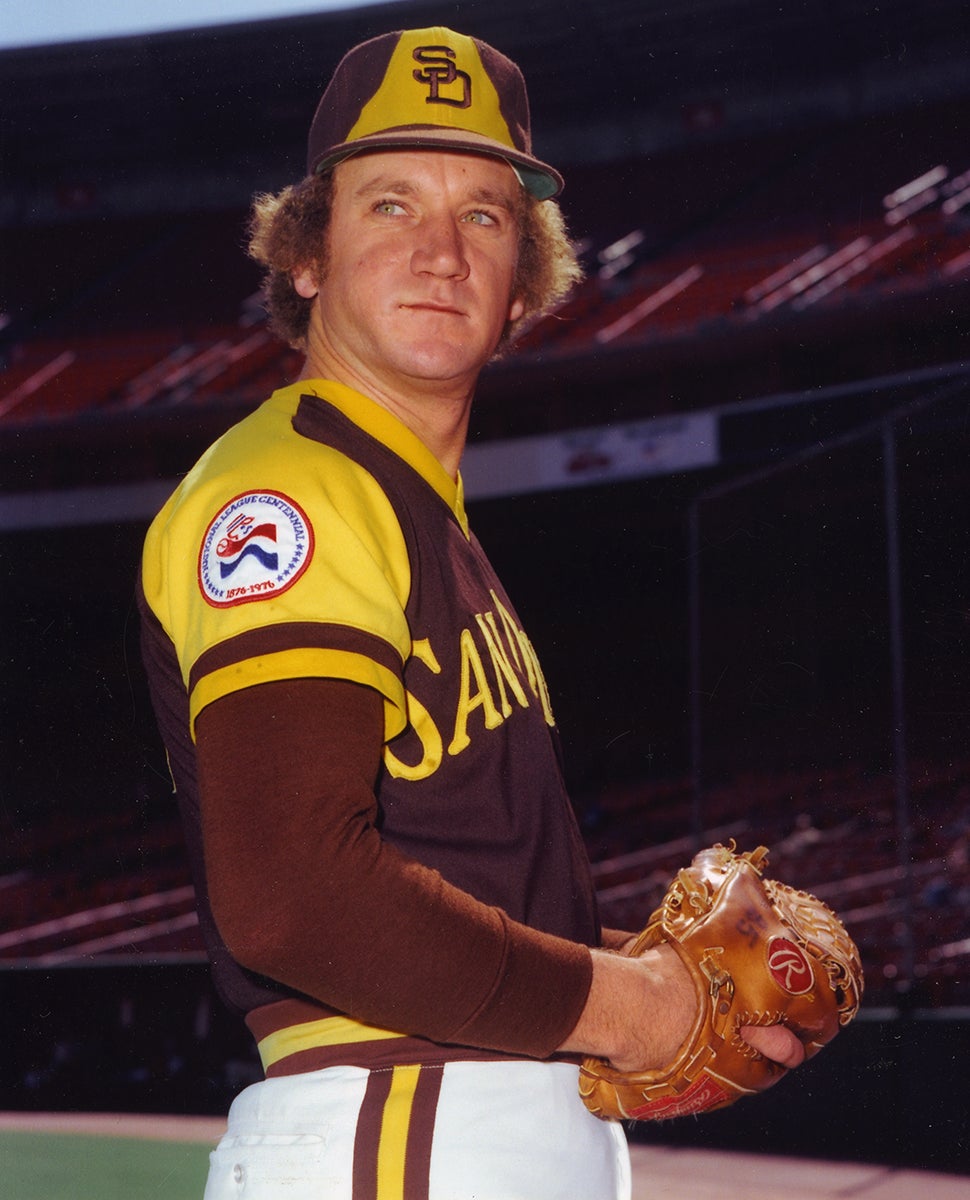

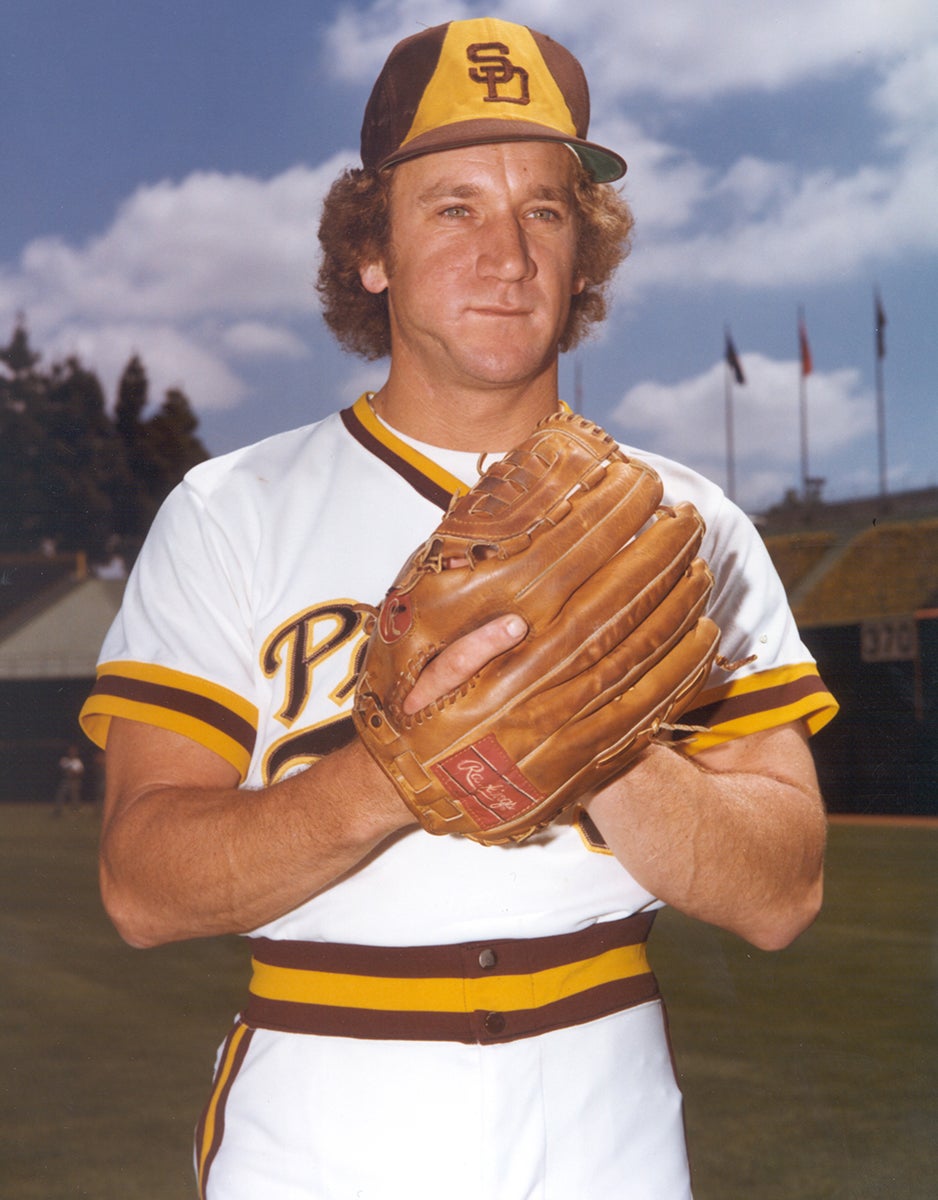

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Randy Jones

He learned to pitch as a teenager with a fastball that many times didn’t even impress high school opponents. But Randy Jones did nothing but rack up innings and outs for season after season en route to one of the most improbable Cy Young Award-winning campaigns in history.

In an era where the first radar guns made velocity king, Jones accomplished with location and trickery what many with raw power never could.

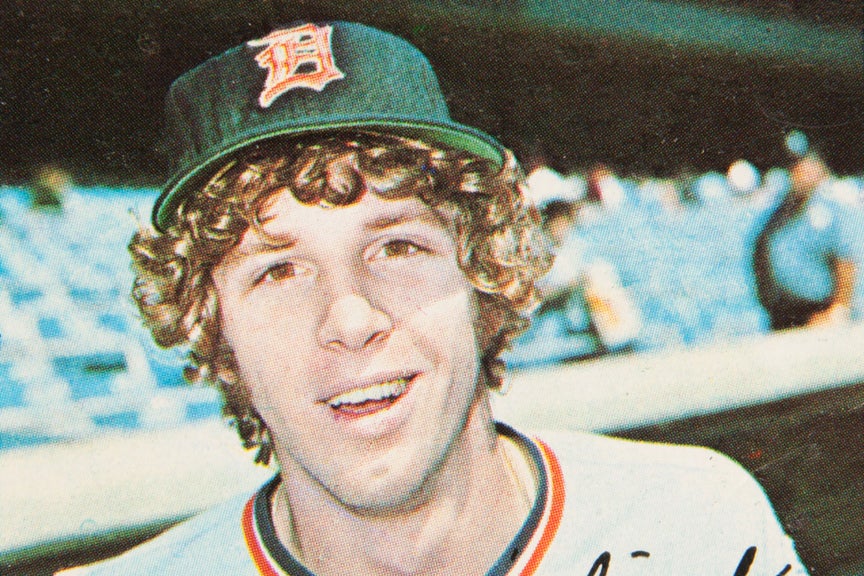

Born Randall Leo Jones on Jan. 12, 1950, in Fullerton, Calif., the lefty starred for Brea Olinda High School while growing into what was listed as a 6-foot, 178-pound frame but was often noted as considerably smaller. He went undrafted out of high school before Detroit Tigers scout Jack Deutch recommended Jones to Chapman College coach Paul Deese. Jones was eventually awarded a half scholarship to Chapman, a private college in Orange, Calif., and enrolled after graduating from high school in 1968.

Deese encouraged all of his hurlers to pitch to contact, something that came easily for Jones. By his sophomore season, Jones was an All-American but still found little interest from big league clubs.

“No one would even give him a chance,” Deese told Copley News Service about Jones’ desire to turn pro after his junior season. “And all he wanted was $1,000 (as a signing bonus). But no one would give it to him. They said he was not a prospect, that he just didn’t throw hard enough. I couldn’t believe it.”

Jones returned to Chapman for his senior year and again was named All-American. In 1970 and 1971, Jones pitched the Anchorage Glacier-Pilots of the Alaska Baseball League to the National Baseball Congress Tournament in Wichita, Kan. In the latter year, Jones outdueled future teammate and Hall of Famer Dave Winfield – then a pitcher for the University of Minnesota – in a 5-4 title game win over the Fairbanks Goldpanners.

Following his 1972 season at Chapman, Deese convinced Padres scout Bob Fontaine to take a chance on Jones – and San Diego selected Jones in the fifth round of the 1972 MLB Draft.

“I asked Bob if big league hitters had weaknesses. He said yes,” Deese said. “I said if they do, then Randy has a chance to pitch in the big leagues because I’ve never, ever had a pitcher in my life who could do more with a batter’s weakness than Randy Jones. You give him a book on somebody and it’s all over.”

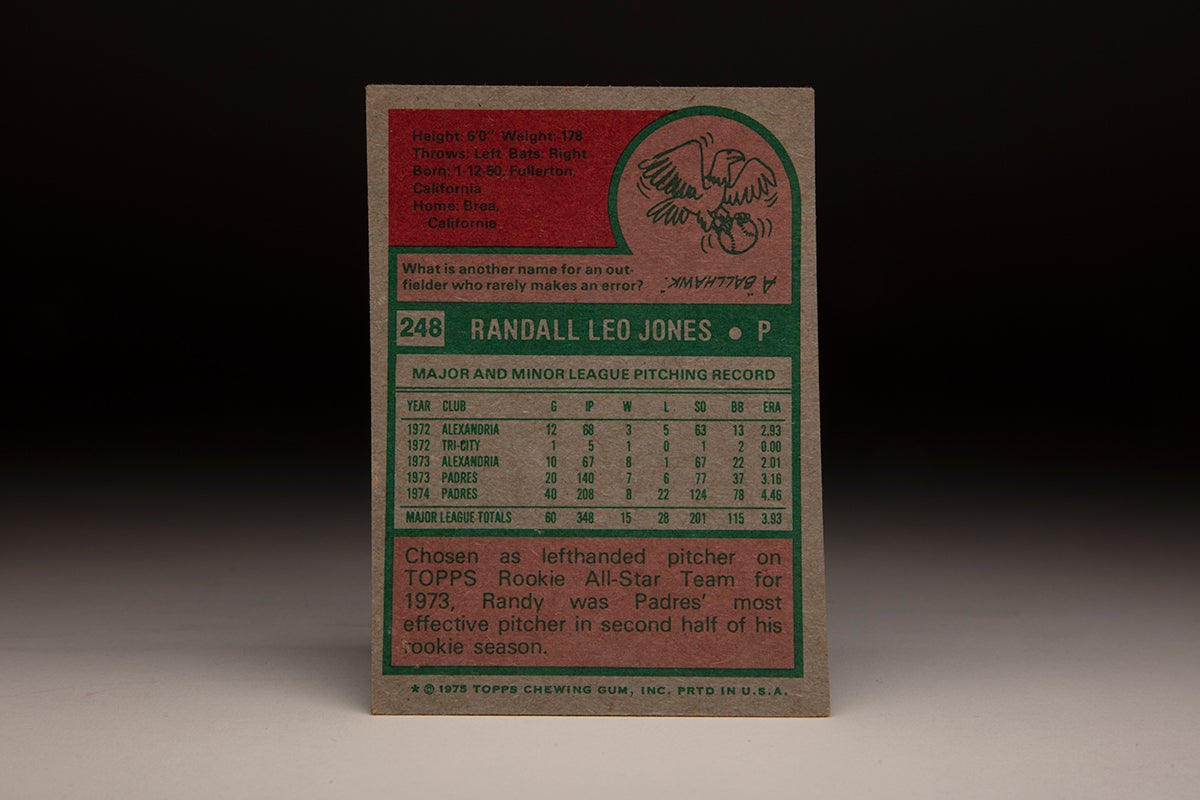

The Padres gave Jones a $3,000 bonus and sent him to Tri-City of the Northwest League, where he made one scoreless start before being promoted to Double-A Alexandria of the Texas League. He returned to Alexandria in 1973, where he was 8-1 with a 2.01 ERA in 10 starts before the Padres promoted him to the big leagues in June.

“I really didn’t think my fastball was good enough when I got (to the big leagues),” Jones told The Town Talk of Alexandria, La., in Spring Training of 1974. “One day in Pittsburgh, when I was warming up, (catcher Pat) Corrales told me my slider and curve and change just didn’t have it and that I would have to go with my sinker.

“I didn’t have any choice, so I threw nothing but fastballs…and I beat them. That gave me confidence in my fastball.”

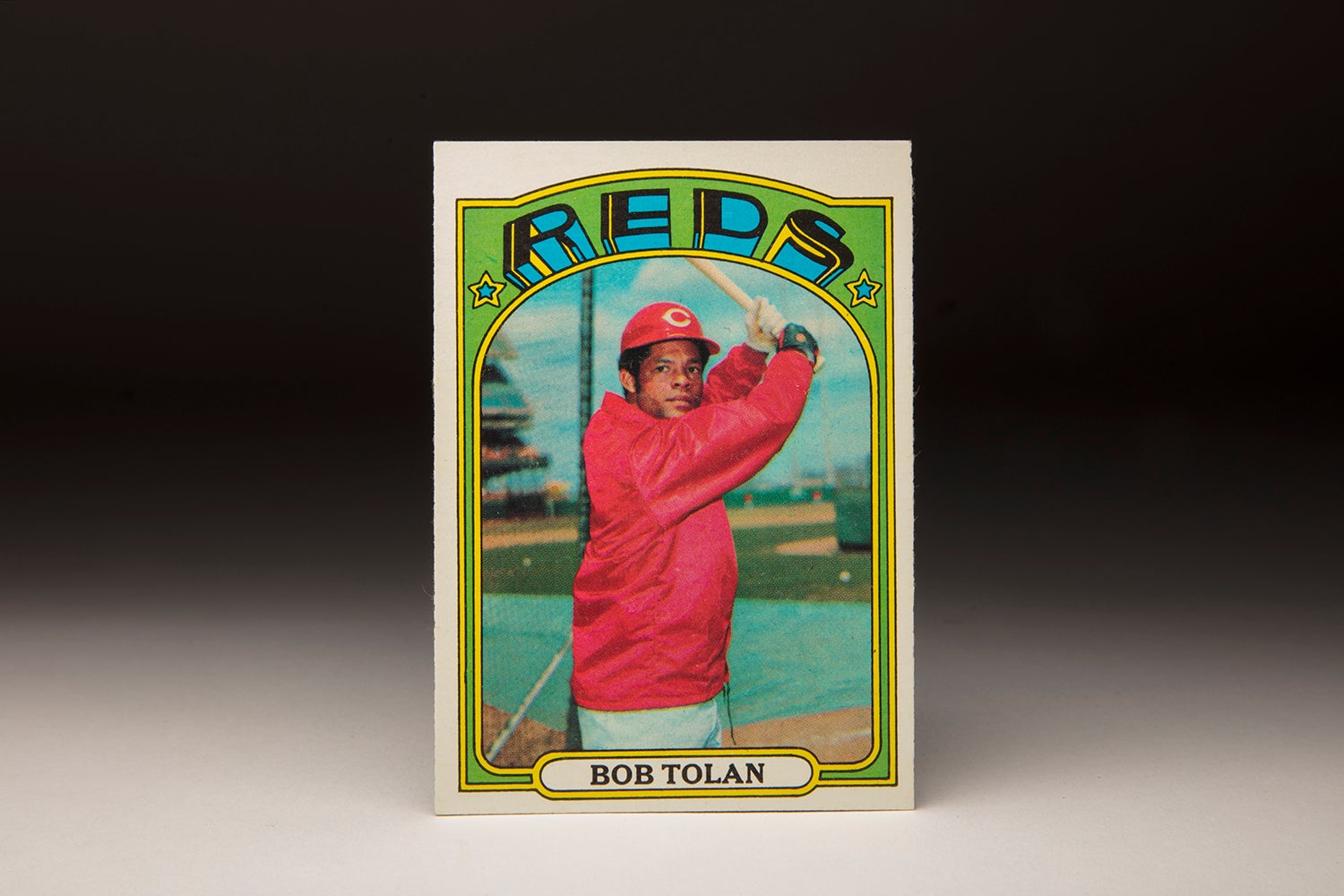

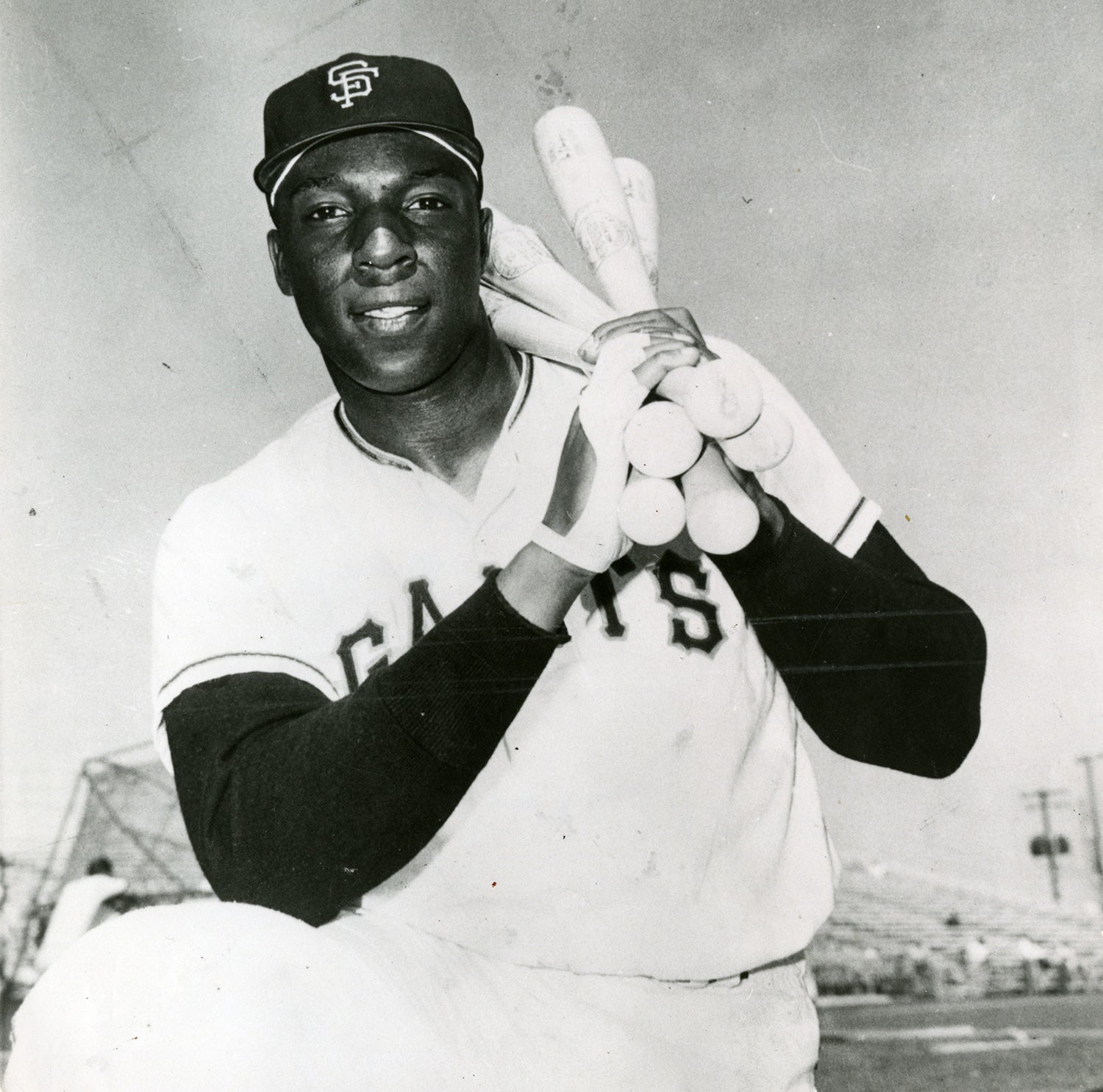

Jones went 7-6 with a 3.16 ERA over 139.2 innings – tossing six complete games and one shutout – and earned a spot on the Topps All-Rookie team. Convinced Jones was ready for regular work at the big league level, the Padres traded pitchers Mike Caldwell and Clay Kirby to the Giants and Reds, respectively, following the 1973 campaign for seasoned hitters Willie McCovey and Bobby Tolan.

“Pitching is our major concern,” Padres manager John McNamara told the Associated Press during Spring Training. “This team has a lot of fine arms but there is cause to wonder if they have developed as they should.”

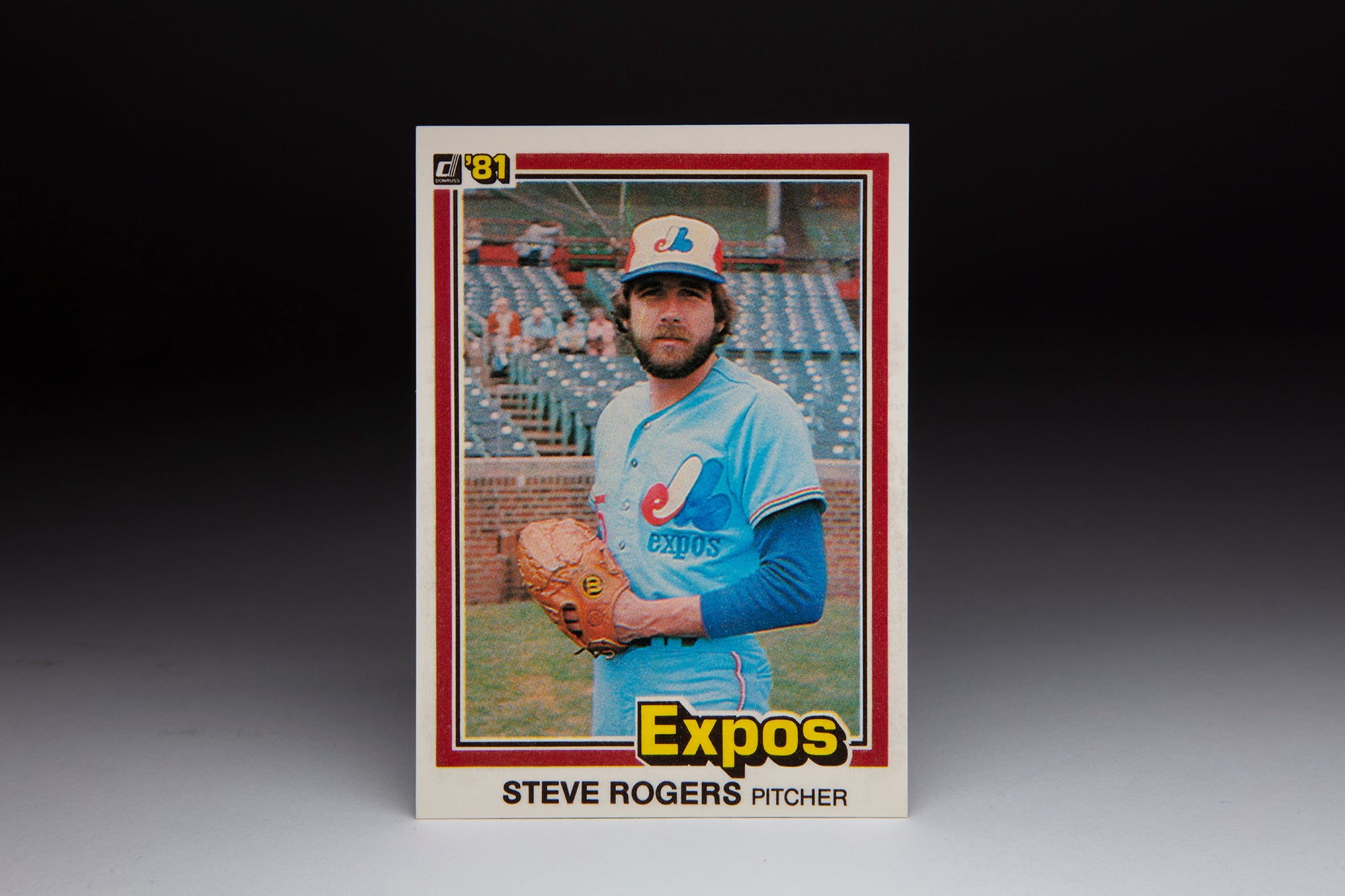

Jones earned a spot in the Padres’ rotation in 1974 and started the team’s second game of the season. But Jones lost his first four decisions, endured an eight-decision losing streak in August and September and finished with a mark of 8-22 with a 4.45 ERA. Jones, Bill Bonham and Steve Rogers tied for the most losses in baseball that year – and no pitcher since has lost as many games in one season.

But in 17 of those losses, the Padres scored a total of 16 runs and were shut out seven times.

“I don’t even like to think about (1974),” Jones told the AP after his second scoreless nine-inning outing of 1975 – a 2-0 shutout over the Astros on April 21. “I have to give most of the credit (for his turnaround) to pitching coach Tom Morgan. He found out about a lot of things I was doing wrong and I worked on them in the spring. For example, he noticed I was using my arm too much. Now I’m using my body more, so I’m stronger in the later innings.”

By the end of May, Jones was 7-2 with four shutouts and a 1.67 ERA. He entered the All-Star Break with a record of 11-6, earning a spot on the National League squad and appearing in the game as a reliever, setting the American League down in order in the ninth inning to secure a 6-3 victory.

“Randy made quite a comeback this year,” Dodgers manager Walter Alston told the AP. “He’s a tough little pitcher. That’s why I picked him for the All-Star Game.”

Jones worked tirelessly throughout the season and notched his 20th win on Sept. 23 vs. the Dodgers, striking out a season-high eight batters while throwing 145 pitches. With the win, he became the first NL pitcher to go from a 20-game loser to a 20-game winner in consecutive seasons since the Cubs’ Dick Ellsworth in 1962-63.

“I’ve never been so tired after a game,” Jones told the AP after recording win No. 20. “This was more pressure than going for a no-hitter or pitching in an All-Star Game.”

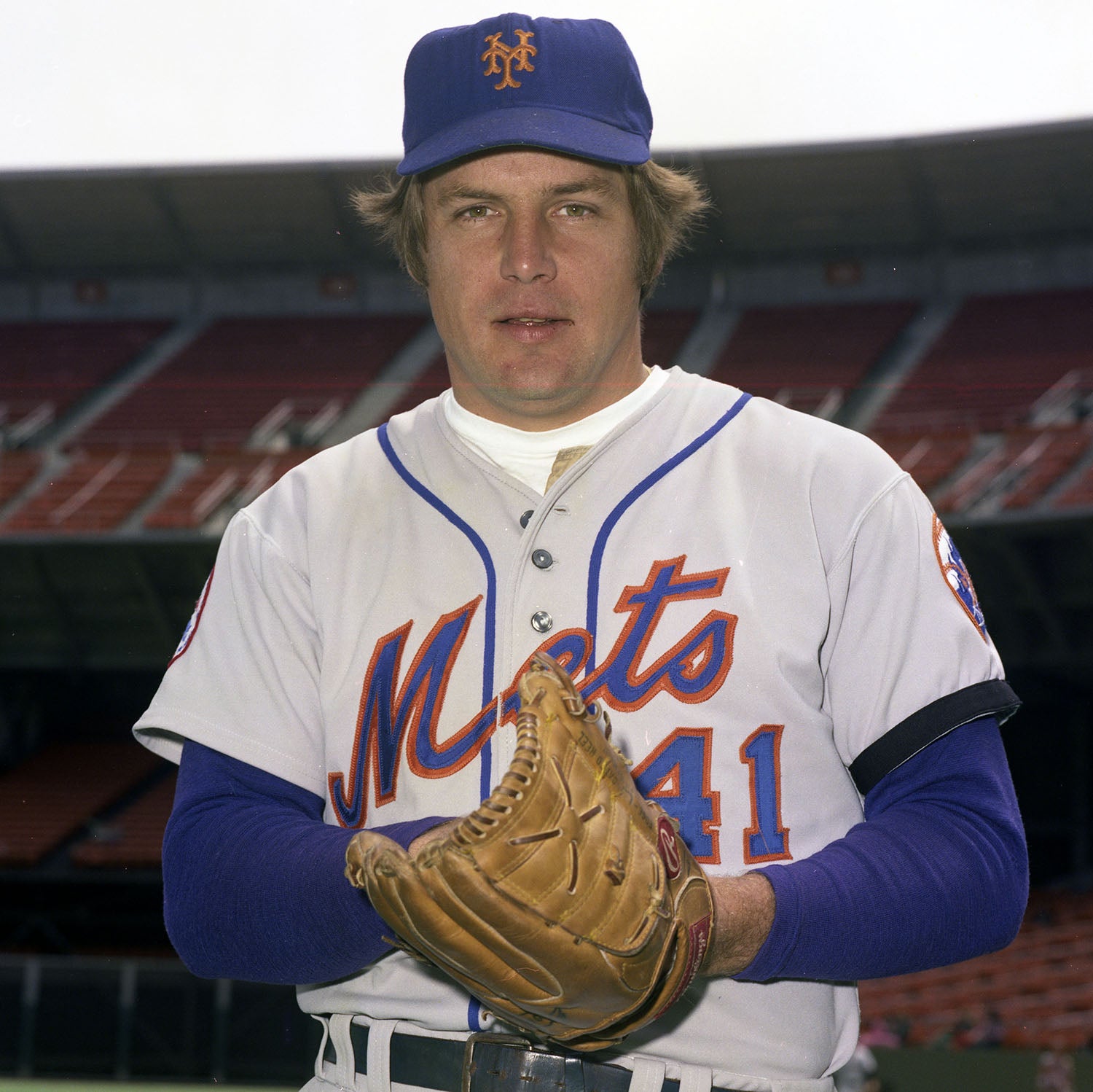

Jones finished the year with a 20-12 record and NL-best 2.24 ERA over 285 innings, including 18 complete games and six shutouts. But Tom Seaver’s 22-9 record and league-leading 243 strikeouts earned the Mets’ ace his third Cy Young Award, with Jones finishing in second place – earning seven first-place votes compared to Seaver’s 15. Jones also finished one spot behind Seaver in the NL Most Valuable Player voting, placing 10th.

“Seaver did a lot for his club, sure,” Jones told the AP following the announcement that Seaver had won the NL Cy Young Award. “But (the Padres) got out of last place for the first time and I’d like to think I had something to do with it. If you think of the award of going to the pitcher who did the most to help his team, I think there were a lot of things favoring me.”

Jones and the Padres agreed to a one-year deal for the 1976 season worth a reported $65,000, more than double his salary of 1975. It turned out to be a bargain when Jones improved his record to 22-14 with a 2.74 ERA, including 25 complete games and five shutouts. He also tied Christy Mathewson’s longstanding record by going 68 innings without allowing a walk.

Many voiced the opinion Jones had a shot at a 30-win season when he found himself with a 16-3 record on July 8 – a mark that earned him the starting nod for the NL in the All-Star Game. He picked up the victory in the NL’s 7-1 win with three shutout innings.

Deese, Jones’ coach at Chapman College, parlayed his connection to Jones – one of the most popular athletes in San Diego during the mid-1970s – into an unlikely job when he was named general manager of the San Diego Jaws of the North American Soccer League in 1976.

“The fact that I was Randy Jones’ college coach is my entrée in this town,” Deese told the Los Angeles Times shortly after being named the Jaws’ general manager. “He’s the hottest thing in San Diego right now.”

But the workload began to take its toll as Jones went 4-10 during August and September. For the year, Jones totaled 315.1 innings while striking out just 93 batters. Pitcher seasons with 300-plus innings and fewer than 100 strikeouts were commonplace in the Dead Ball Era – almost 200 have been recorded in MLB history – but when Jones reached that milestone, no one had done it in 48 years. Predictably, no one has done it since.

On Nov. 2, Jones was named the winner of the National League Cy Young Award, more than doubling the first-place votes (15 to 7) of runner-up Jerry Koosman of the Mets. But before Jones could collect the hardware, he underwent surgery to repair a severed nerve near his biceps tendon – an injury that occurred in his final start of 1976.

“I couldn’t make a muscle,” Jones told the AP. “The doctor said the nerve had been fatigued to the point that it wasn’t working.

“Everything I had worked for for the last two years could have gone up in smoke. I thought my career was over.”

Doctors prepared Jones for the possibility that he would undergo Tommy John surgery – a procedure less than three years old at the time. But with the nerve reattached, doctors felt Jones would pitch again in 1977.

On Dec. 23, 1976, Jones agreed to a three-year deal worth $420,000 – a huge raise from his previous salaries but a figure that would soon be dwarfed by other contracts in the new era of free agency.

“When this three-year contract ends, I’ll be bargaining again,” Jones told United Press International. “Over a six-year period – well, I have my own ideas about who will be getting more money.”

But Jones would never again be the elite pitcher he was from 1975-76.

In 1977, Jones was forced onto the disabled list in June when his left biceps muscle began to atrophy because the nerve was not functioning properly. He made just 25 starts that year, working 147.1 innings while going 6-12 with a 4.58 ERA.

He bounced back in 1978 with a 13-14 record and 2.88 ERA in 253 innings. But the control he had exhibited at the peak of his career began to elude him. After leading the NL in WHIP in 1976 with a 1.027 mark (walking just 50 batters over his 315.1 innings), Jones posted a WHIP of 1.292 in 1978.

Jones made 39 starts in 1979 and was 11-12 with a 3.63 ERA over 263 innings. The Padres, with future Hall of Famers Rollie Fingers, Ozzie Smith and Dave Winfield in the fold, signed Jones to a five-year extension in September of 1979 – a deal worth a reported $2 million that would carry Jones through the 1984 campaign.

“I’ll never forget the appreciation of the fans,” Jones told the Escondido (Calif.) Times-Advocate. “The fans stayed with me. I hope I don’t let them down the next five years. I want to bring a winner to the people of San Diego and (team owner) Ray Kroc.”

The Padres would become winners in five years, capturing the franchise’s first NL pennant in 1984. But Jones would not be a part of that team.

Jones began the 1980 season in fine form, tossing three straight shutouts from May 6-16 to improve his record to 4-2 with a 1.82 ERA. But in his next start on May 21 vs. Pittsburgh, Jones was hit with the same left-arm nerve injury that had plagued him in 1977. He was placed on the disabled list in June, returned in July and then made his last start of the season Aug. 22 before once again heading to the DL. He finished the year with a 5-13 record and 3.91 ERA in 24 starts.

On Dec. 15, 1980, the Padres traded Jones to the Mets in exchange for outfielder José Moreno and pitcher John Pacella.

“Randy Jones knows how to pitch,” Mets manager Joe Torre told the AP following the trade. “He’s a master on the mound. He doesn’t win with his fastball, he wins because of his knowledge of the game and because he knows where to put the ball on each hitter.”

Jones started the second game of the year for the Mets in 1981 but lost his first five decisions and was 1-7 with a 3.97 ERA when the strike interrupted the season in June. He made only two more appearances that year and finished 1-8 with a 4.85 ERA.

The Mets replaced Torre with George Bamberger for the 1982 campaign, and Jones seemed re-energized in Spring Training.

“I was glad when Bamberger was named manager because he’s got the reputation of being a pitcher’s manager, and that’s what I need,” Jones told The New York Times News Service. “I’m working to get back in the groove.”

Jones got the Opening Day start for the Mets in 1982 – his first since 1980 and his fifth overall. He was 6-2 with a 2.74 ERA on May 23 after shutting out the Astros but his fortunes cratered from there as the Mets lost 16 of his last 17 appearances of the season. Jones finished the year with a 7-10 record and 4.60 ERA in 107.2 innings and was particularly ineffective at Shea Stadium, where he was 3-8 with a 7.47 ERA after going 1-6 at Shea in 1981. But on the road in 1982, Jones was 4-2 with a 2.37 ERA.

On Nov. 5, the Mets released Jones.

“I just couldn’t get comfortable there,” Jones told the AP in the spring of 1983 after hooking on with the Pirates. “I felt healthy. But for some reason, pitching in Shea Stadium just threw my gyroscope off.”

But Jones was unable to recapture his equilibrium with Pittsburgh, and on March 27, 1983, the Pirates released him. He would not pitch in the big leagues again.

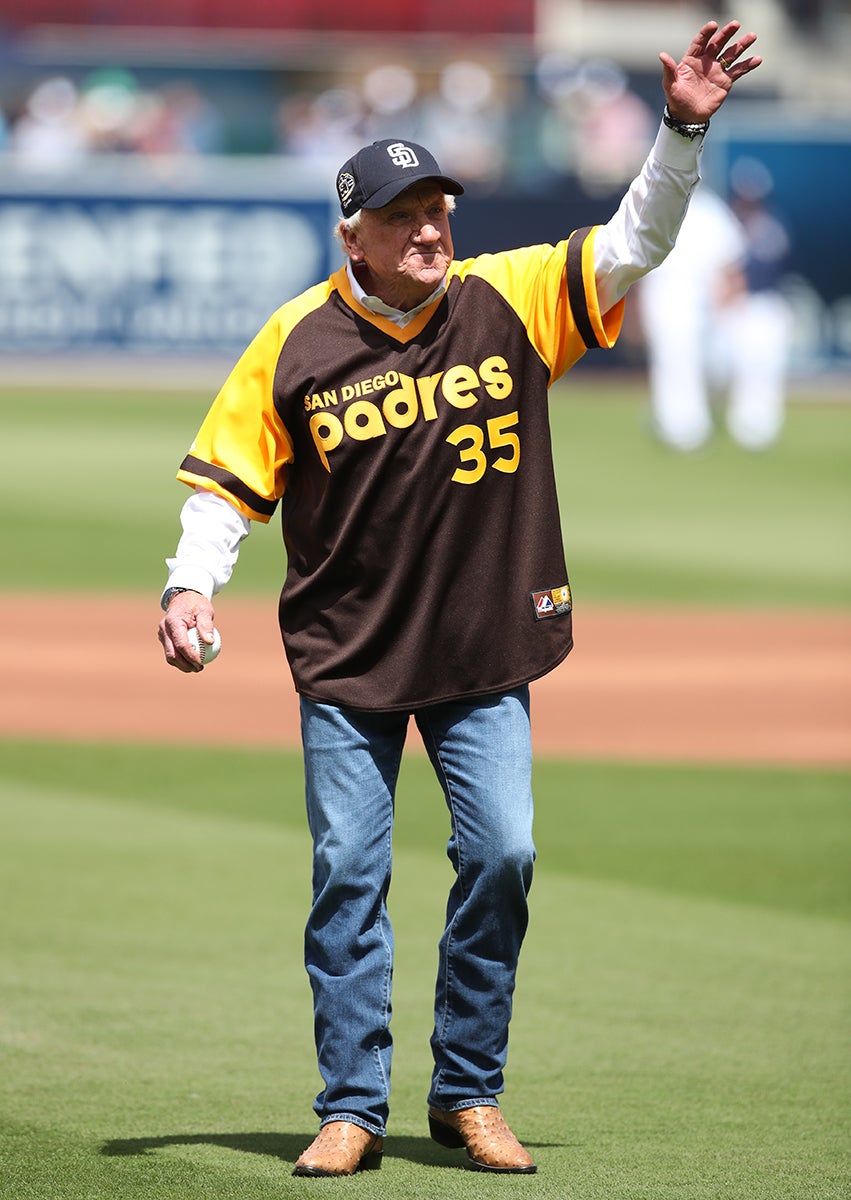

In his retirement, Jones partnered with his former college coach Paul Deese in several food service businesses, including a barbeque venture at the Padres’ home ballpark in San Diego. He also worked with young pitchers in Southern California, including 2002 American League Cy Young Award winner Barry Zito – another left-handed control pitcher – before Jones passed away on Nov. 18, 2025.

Jones finished his career with a mark of 100-123 and a 3.42 ERA, including 73 complete games and 19 shutouts. And though he struck out only 735 batters over 1,933 innings, Jones consistently found ways to retire batters with an assortment of change-of-pace pitches off a fastball that often dipped below 80 miles per hour.

“I depend on my teammates to be effective,” Jones told the Times-Advocate in 1979. “I’m a ground ball pitcher. But I know I have to do my part. I have to go as hard as I can and pitch consistently.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum