- Home

- Our Stories

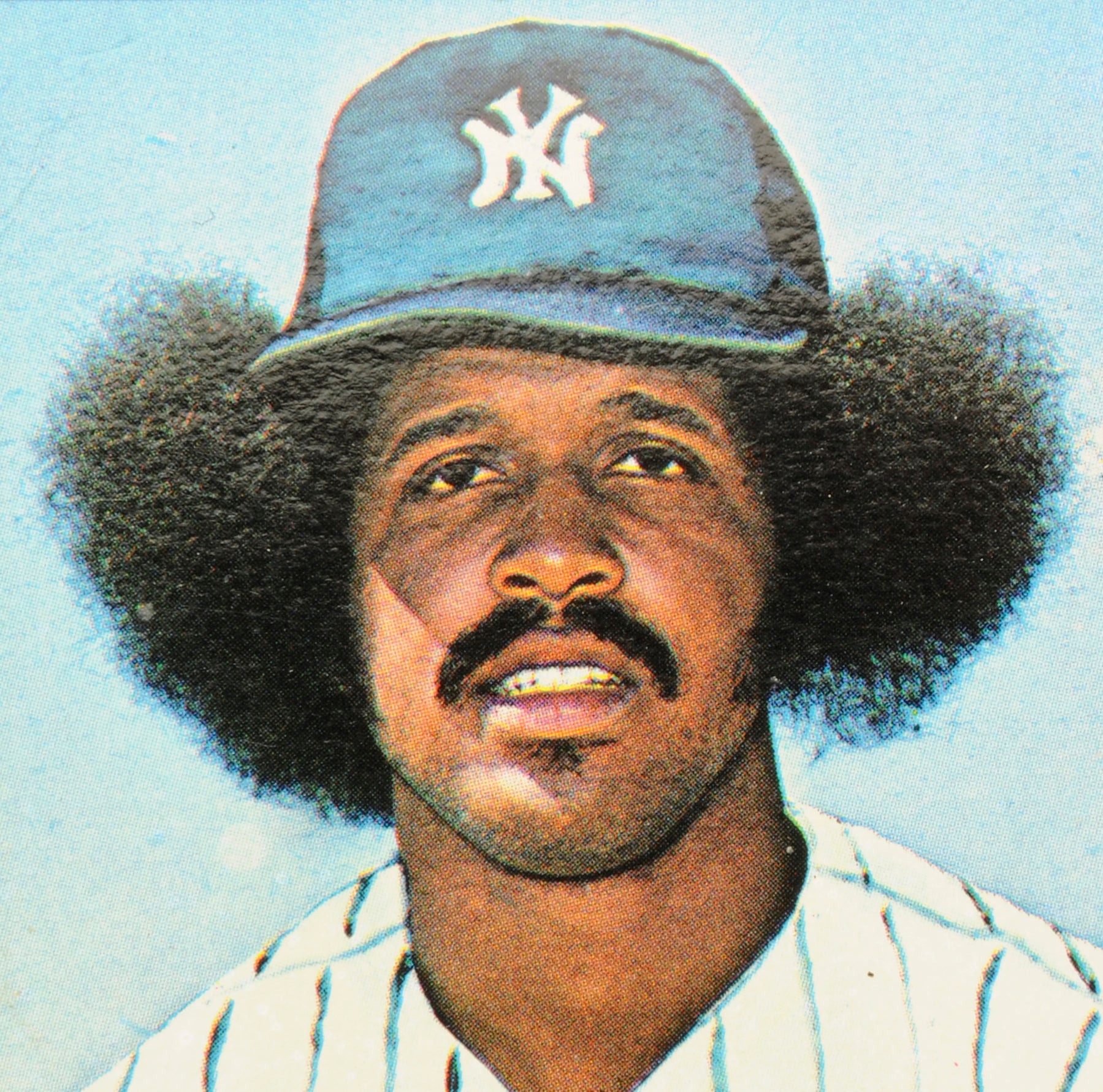

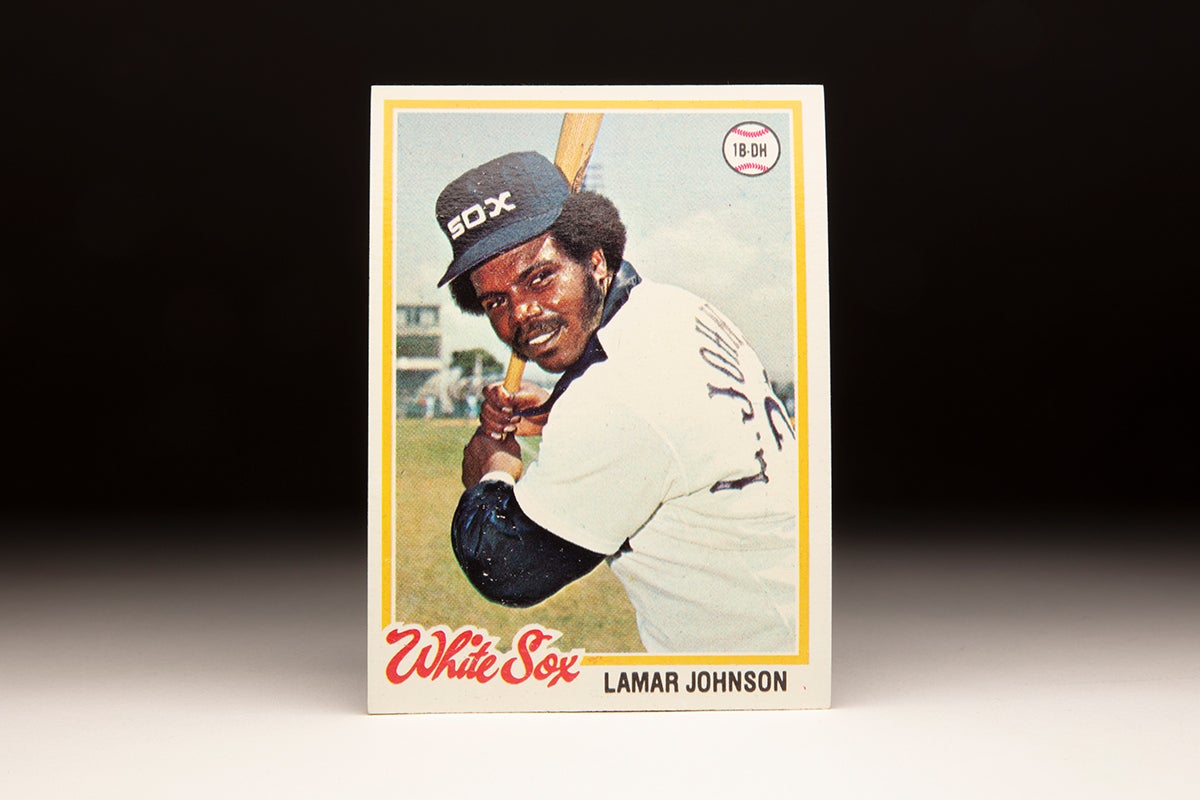

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Lamar Johnson

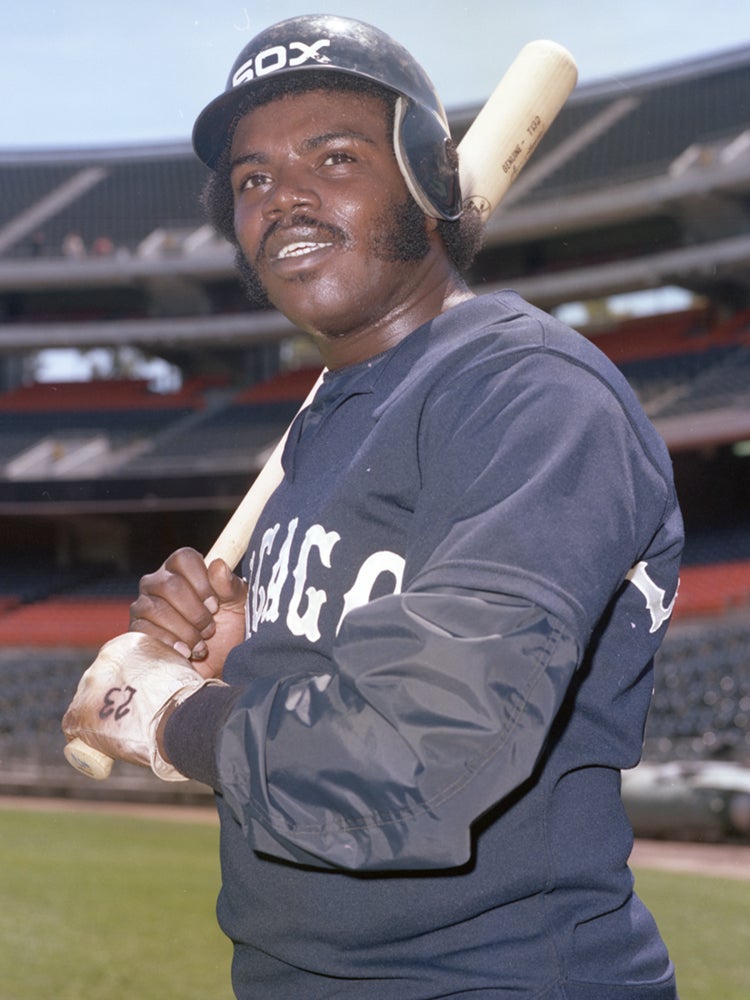

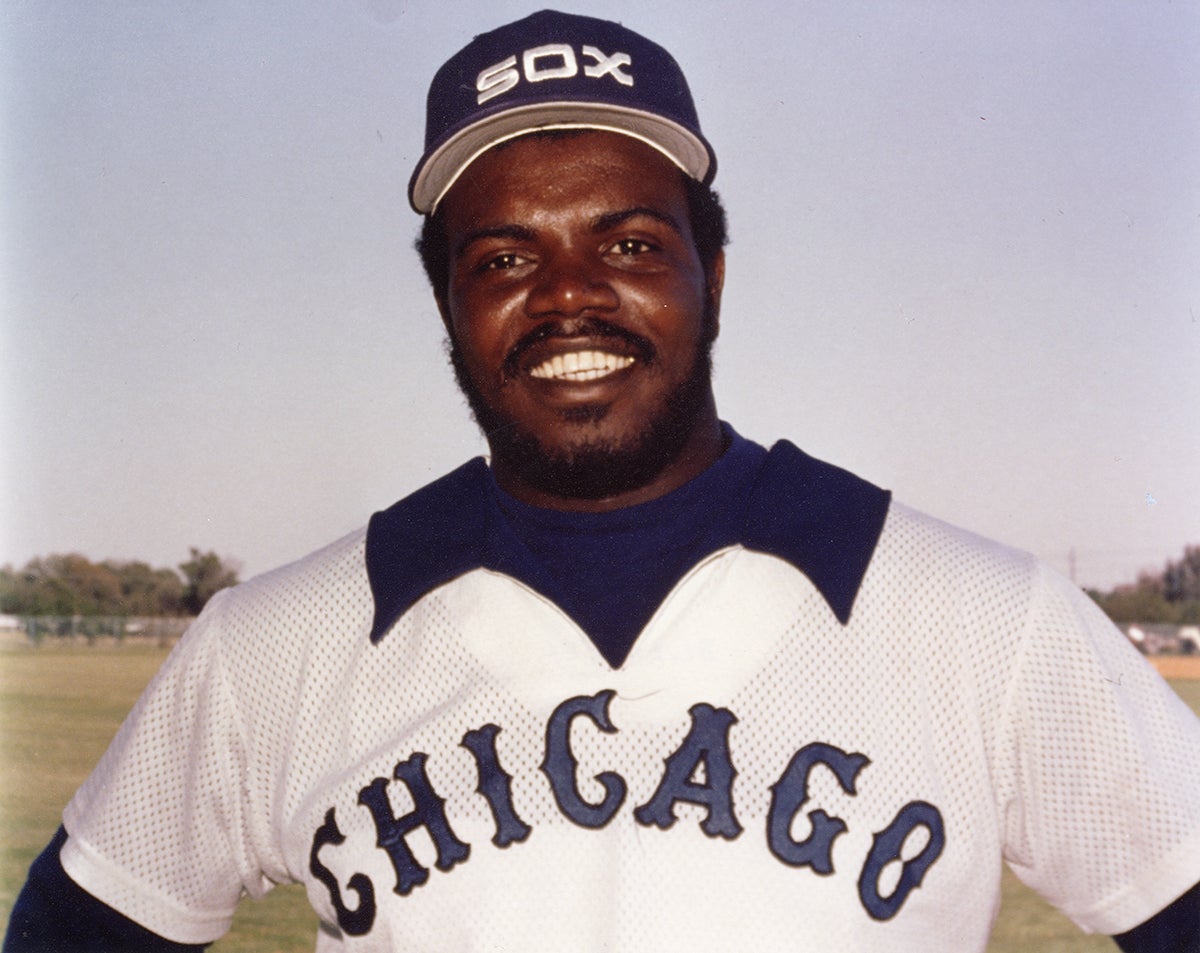

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Lamar Johnson

The 1977 Chicago White Sox became the talk of baseball that summer with a potent lineup that featured one-year “rent-a-players” brought into the fold by legendary owner Bill Veeck.

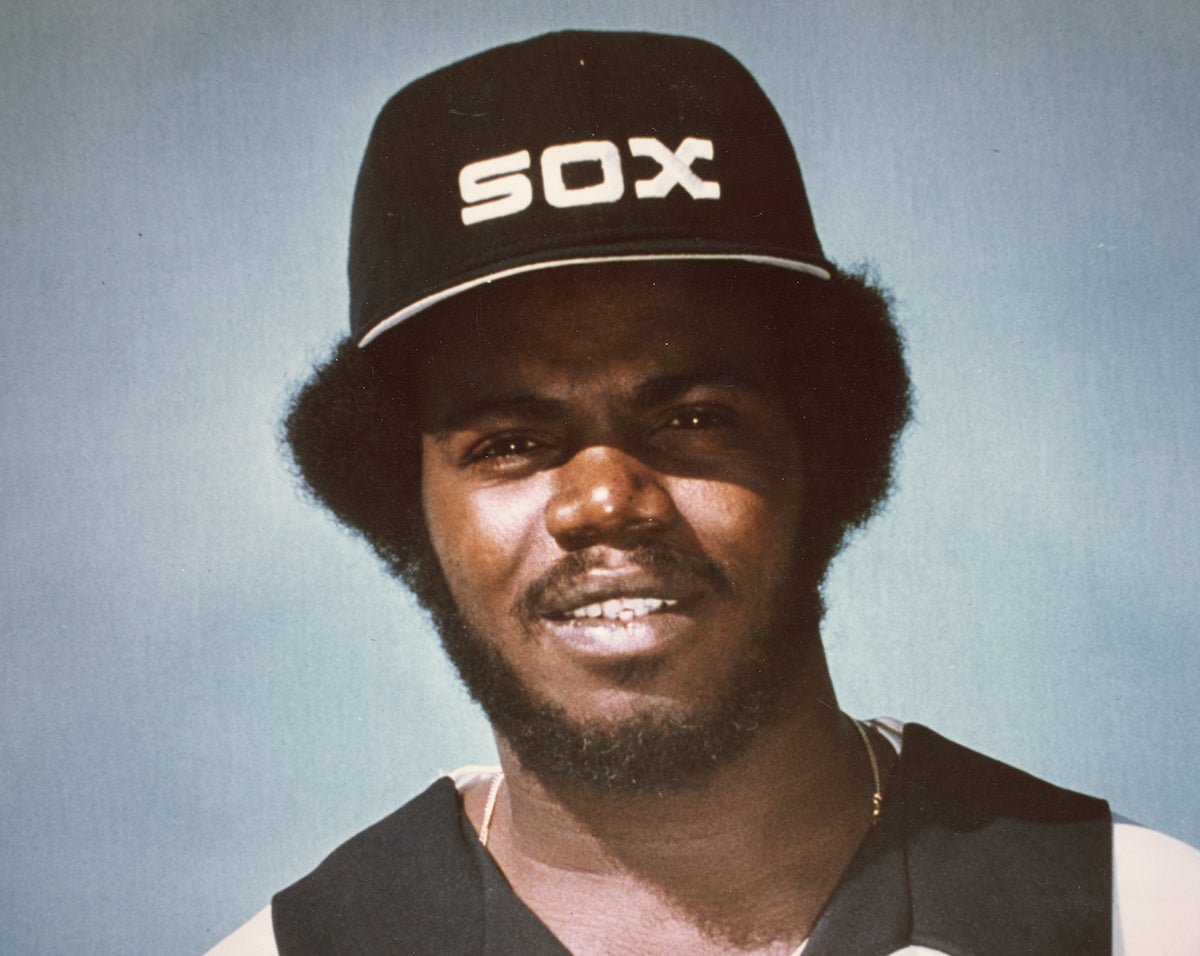

But it was a homegrown talent – first baseman Lamar Johnson – who produced what was arguably the high-water mark of the Sox’s season.

Few players at any level can say they sang the national anthem before hitting two home runs and helping their team vault into first place. But that’s what Johnson accomplished one sunny day at Comiskey Park.

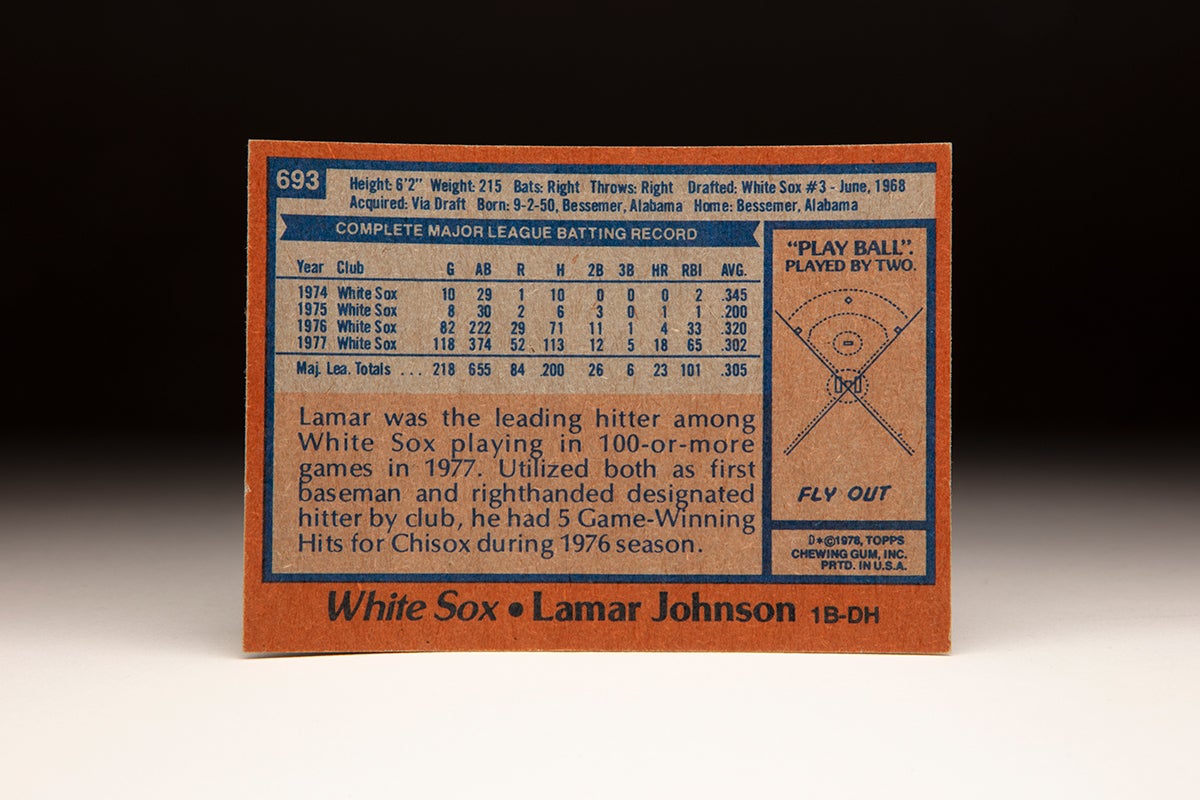

Born Sept. 2, 1950, in Bessemer, Ala., Johnson was one of 11 children whose father was an ore miner. A football and baseball star at Wenonah High School in Birmingham, the 6-foot-2, 215-pound Johnson had the potential to be a college football lineman.

“I was a tackle in high school and had chances to go to Wichita State and Grambling on scholarship,” Johnson told the Des Moines Register in 1974. “I thought about that a lot, but I have no regrets. Baseball has been good to me so far.”

On the high school diamond, Johnson was a catcher and cast his lot with baseball when he was selected in the third round of the 1968 MLB Draft by the White Sox. Sam Hairston, who starred in the Negro Leagues before playing four games for the White Sox in 1951, signed Johnson and sent him to the team’s Gulf Coast League outpost in Sarasota, Fla. Johnson hit .383 in 20 games and returned to Sarasota in 1969, when he was moved to the outfield.

Then in 1970, Johnson transitioned to first base with Duluth-Superior of the Class A Northern League. He hit .321 with six home runs in 55 games, earning an assignment with Class A Appleton in 1971. The Foxes were loaded with talent that season, going 79-44 on the strength of a roster that included future big leaguers Bucky Dent, Brian Downing, Jerry Hairston (son of Sam Hairston) and Goose Gossage – who went 18-2 with a 1.83 ERA. Johnson was nearly as dominant as Gossage, hitting 18 homers and driving in 97 runs. No other teammate had more than eight homers or 59 RBI.

“I was a catcher my first two years of pro ball but was switched to first base because I had a bad arm,” Johnson told the Des Moines Register. “I didn’t like catching anyway.”

Johnson returned to Appleton in 1972 and led the Midwest League with 89 RBI while batting .313 with 26 homers in 114 games. He earned a late-season promotion to Double-A Knoxville then spent the entire 1973 campaign at that level, hitting .293 with 16 homers and 93 RBI in 138 games. Following that season, Johnson batted .327 with 11 home runs for Sarasota of the Florida Winter Instructional League.

But while he appeared to be ready for big league play, Johnson was blocked at first base by future Hall of Famer Dick Allen, who won the 1972 American League MVP with the White Sox and was hitting .316 with 16 homers and 41 RBI through 72 games in 1973 when a collision with the Angels’ Mike Epstein on June 28 resulted in a broken leg that – save for three late-season games – ended his season.

Allen was also the highest paid player in the game at the time, making a reported $225,000 in 1973. So Johnson knew he would have to bide his time.

“The White Sox have Dick Allen at first base, of course,” Johnson told the Des Moines Register in the spring of 1974 after he was sent to Triple-A Iowa. “Maybe my opportunity won’t come with Chicago because Allen will play most of the time, but somebody will give me a chance if the Sox don’t.”

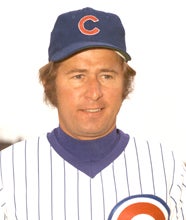

Johnson might have gotten his chance in 1974 if the White Sox hadn’t traded for another future Hall of Famer – Ron Santo – prior to the season. Santo spent most of 1974 as the White Sox’s designated hitter.

“If Santo hadn’t joined the Sox, Lamar Johnson would probably be their designated hitter this season,” Iowa Oaks manager Joe Sparks told the Des Moines Register in the spring of 1974. “He’ll hit at least 25 homers (for the Oaks in 1974).”

Sparks was off by five home runs but Johnson still had another outstanding season, batting .301 with 20 homers and 96 RBI. Then, with a little more than two weeks left in the 1974 season, Allen abruptly announced his retirement – yet still went on to win the AL home run title with 32 long balls. The White Sox quickly recalled Johnson, who had made his big league debut in May with a quick four-game trial.

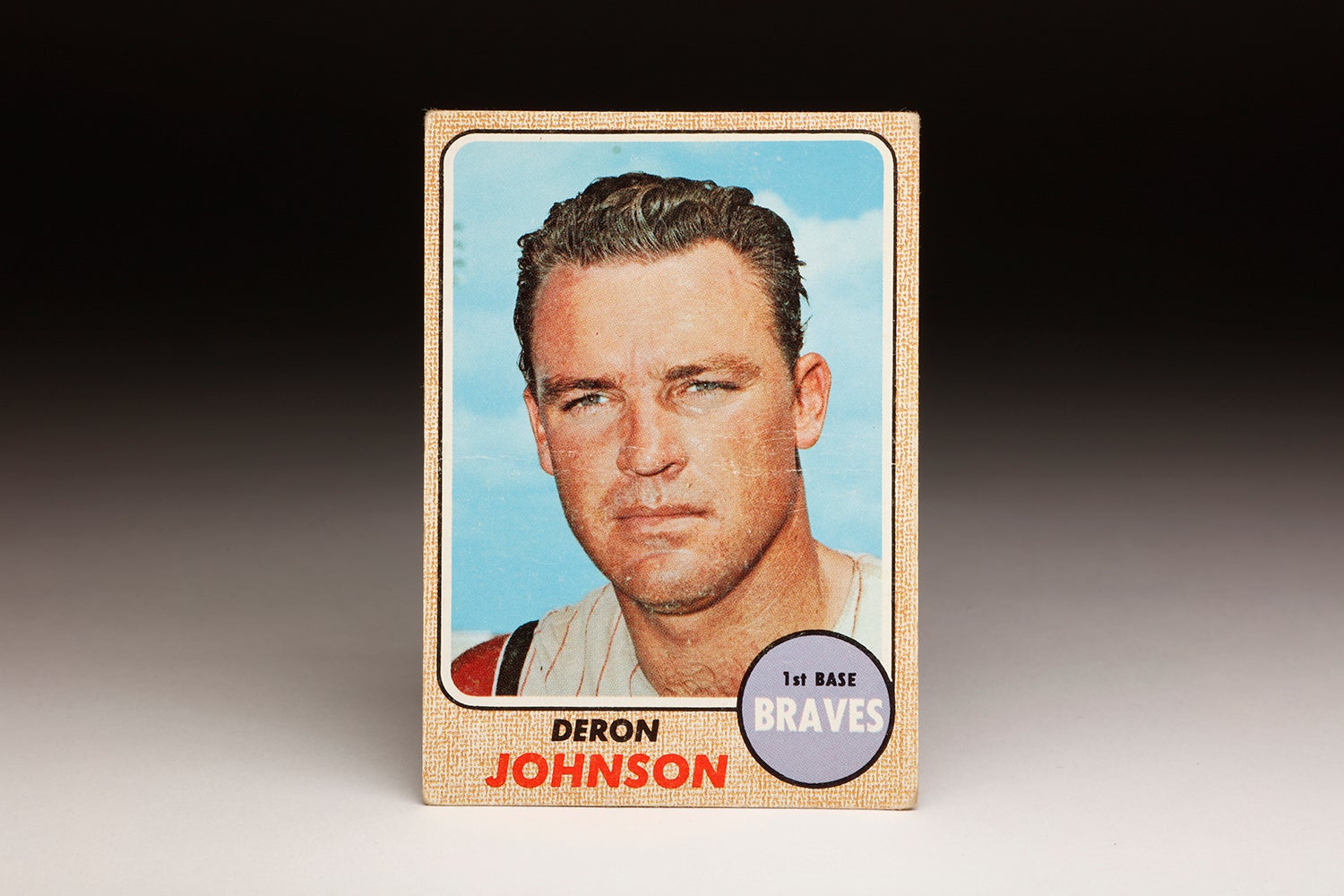

Playing six games at first base after Allen’s departure, Johnson hit .429 with two RBI. Allen later decided to continue his career and was traded to Atlanta, and Santo retired – seemingly opening a spot for Johnson in 1975. But the White Sox went with veteran Tony Muser at first base to start the season and brought in veteran Deron Johnson just before Opening Day, sending Lamar Johnson to Triple-A Denver.

The moves left Johnson angry at White Sox manager Chuck Tanner.

“Chuck Tanner buried me for years,” Johnson told the Chicago Tribune in the spring of 1976. “I did everything I possibly could in the minor leagues for years, and yet I never even got a chance from him.

“When Dick Allen was playing for the White Sox, I could see maybe why they kept me down. But last year, that was the last straw.”

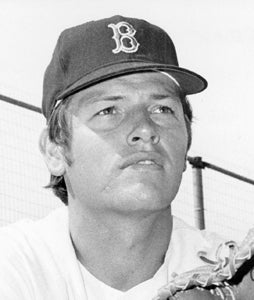

Once again, Johnson torched Triple-A pitching – batting .336 with a .398 on-base percentage, 20 homers and 101 RBI in 129 games before earning another September call-up. In his first big league game of the 1975 season, Johnson hit his first MLB homer – a solo blast off the Angels’ Frank Tanana on Sept. 10 in Chicago.

The White Sox, meanwhile, endured a difficult season in 1975, going 75-86 while trying to focus on team speed rather than power. Tanner became the Athletics manager in 1976 and was replaced by Paul Richards, who kept Johnson on the Opening Day roster and platooned the right-handed hitting Johnson with lefty Jim Spencer as the season progressed.

“This is the first time in my life,” Johnson told the Tribune, “that I feel I’ll be in camp and be judged on what I do.”

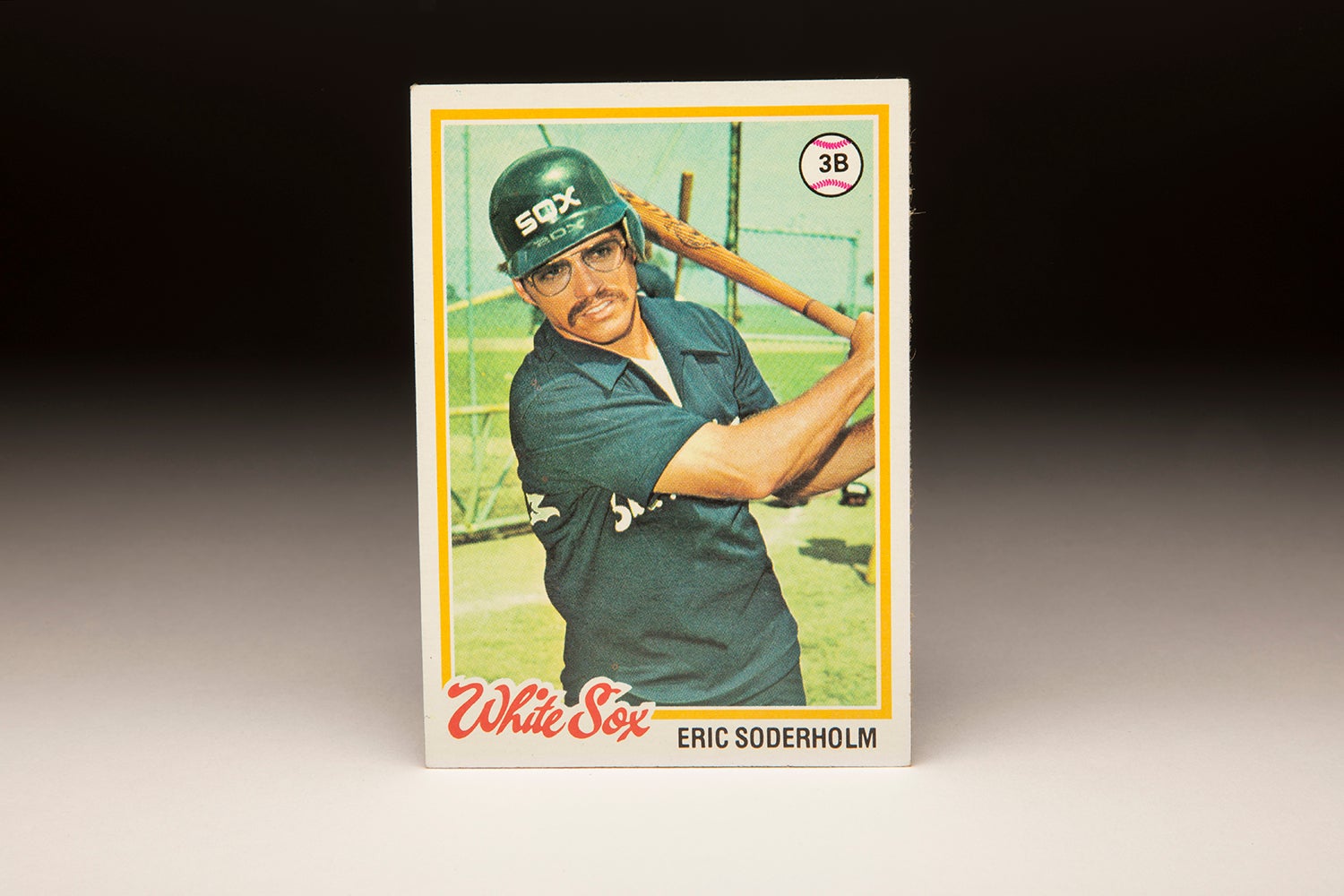

In 82 games that year, Johnson hit .320 with four home runs and 33 RBI. But Chicago lost 97 games, leading Veeck to replace Richards with Bob Lemon and to embrace – in an unconventional way – the new free agency system.

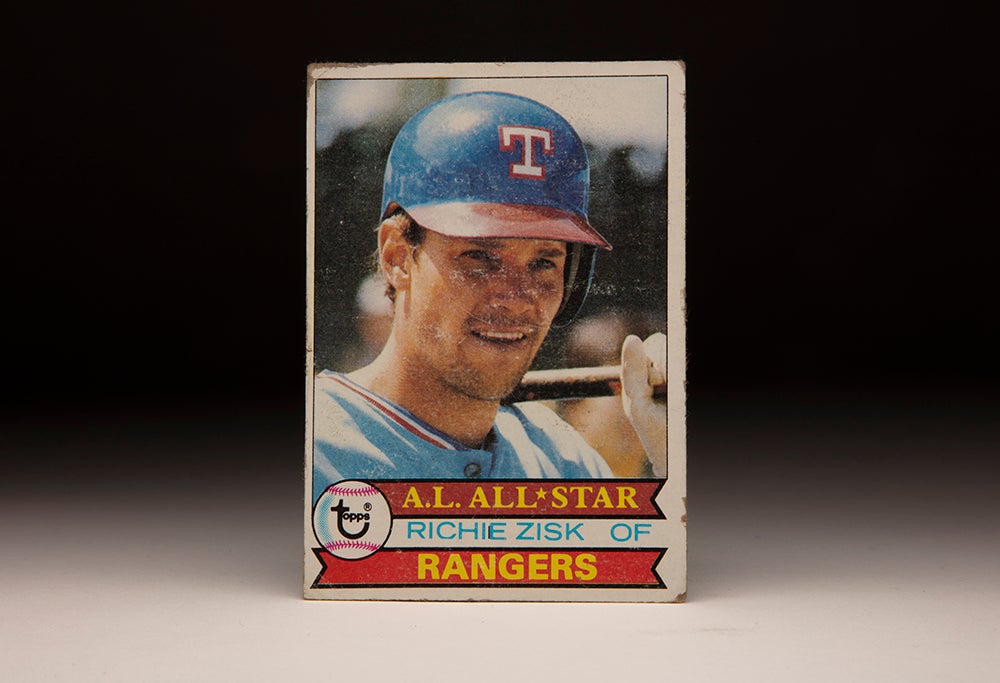

Prior to the 1977 campaign, Veeck traded for veterans Oscar Gamble and Richie Zisk, both of whom were set to become free agents following the season. The plan worked as the White Sox scored 844 runs – third-most in the AL – and hit 192 home runs, earning the nickname The South Side Hitmen. Johnson continued his platoon with Spencer at first base and saw time at DH, hitting .302 with 18 homers and 65 RBI in 118 games.

On June 19, Johnson and the White Sox hosted the Athletics in a Sunday doubleheader. Johnson, who had performed in musicals in high school and was an accomplished singer, was asked if he would consider singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” before Game 1.

“(White Sox pitcher) Bart Johnson talked to Bill Veeck’s secretary about my singing the anthem,” Johnson told the Associated Press. “I said OK.”

Johnson proceeded to go 3-for-3 in Game 1, hitting two home runs off Oakland starter Mike Norris in a 2-1 victory. Johnson had another hit and scored a run in Chicago’s 5-1 win in the nightcap – a victory that left the White Sox at 35-27, two percentage points in front of Minnesota for first place in the AL West.

“If singing means I hit like that, I’ll sing anytime they want,” Johnson told the AP.

The White Sox finished in third place with a record of 90-72, and Johnson was seen as one of the team’s core players. At 27 years old, Johnson had finally earned a regular spot in the White Sox’s lineup.

Entering Spring Training in 1978, Johnson was expected to get the majority of playing time at first base even though the White Sox signed veteran first sacker Ron Blomberg to a lucrative free agent deal that winter. Blomberg was injured much of the season, however, and Johnson started at first base on Opening Day. He was hitting .297 in early May when a prolonged slump kept him hovering around the .245 mark deep into July. He parlayed a strong August into a final push that left him with a .273 batting average, eight home runs and 72 RBI in 148 games.

“I’m an aggressive swinger, and I’ve got to stay that way,” Johnson told the Chicago Tribune as he emerged from his slump in late July. “I told myself not to get cheated at the plate. I’d been swinging defensively.”

Johnson regained his swing in 1979 when he hit .309 with 12 homers and 74 RBI in 133 games. He also posted a career-best 29 doubles while striking out only 56 times, focusing on contact rather than trying to test Comiskey Park’s vast outfield dimensions.

He put up similar numbers in 1980, hitting .277 with 26 doubles, 13 homers and 81 RBI. He even won AL Player of the Month honors for April, batting .381 with four homers and 17 RBI.

But the White Sox lost 87 games in 1979 and 90 a year later, prompting management to bring in future Hall of Famer Carlton Fisk and slugger Greg Luzinski. Manager Tony La Russa then decided to go with gloveman Mike Squires at first base on Opening Day, relegating Johnson to the bench.

“I don’t know why they are making me out to be a scapegoat for them not winning before,” Johnson told United Press International early in the 1981 season. “I did my best. Look at my statistics. I led this team in RBI last year. I felt after last year I was ready to have an even better year this season. Then all of this came down.”

Rumors abounded that spring that the White Sox were shopping Johnson, who was set to become a free agent at season’s end and who was part of a backlog of right-handed DH candidates in the Chicago clubhouse – a group that also included Wayne Nordhagen and Luzinski.

But the White Sox held onto Johnson.

“You look at all the strong teams in the American League. They all have strong benches,” White Sox general manager Roland Hemond told UPI. “That’s what we want to have here and Lamar fits the bill.”

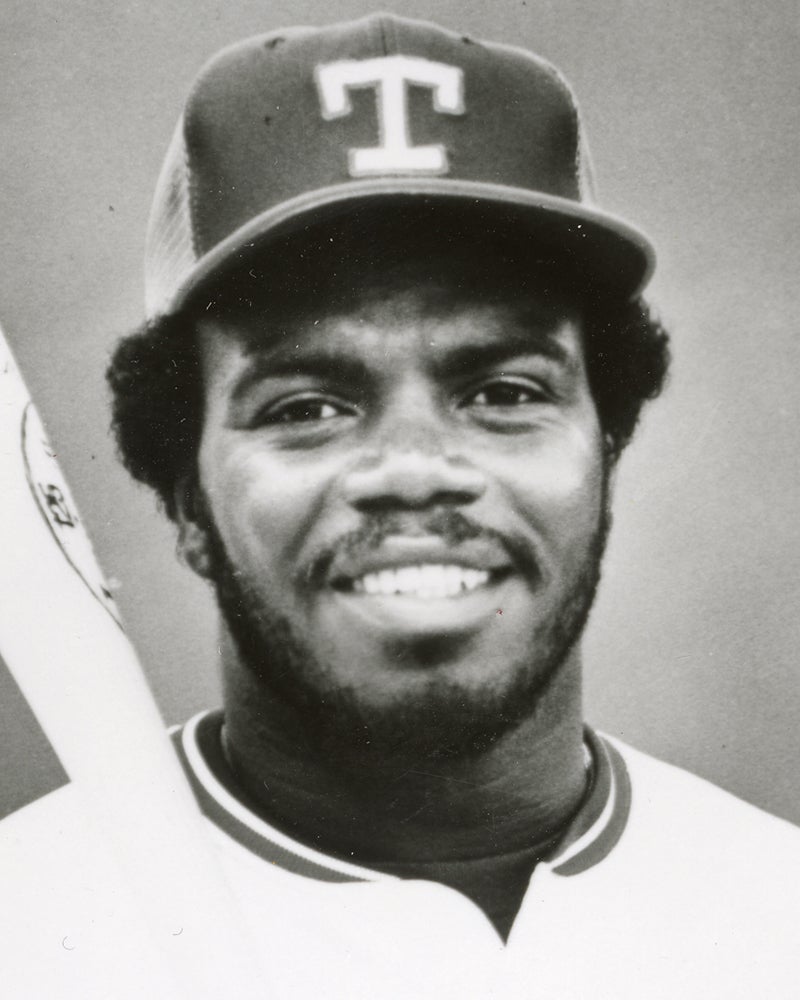

Johnson appeared in just 41 games in the strike-shortened 1981 season, batting .276 with a home run and 15 RBI for a White Sox team that went 54-52. He became a free agent after the season and was selected by the Blue Jays and the Rangers in the re-entry draft, a process that left Johnson able to negotiate with all 26 MLB teams. He and his agent George Andrews soon began serious negotiations with the Rangers.

“They’ve got a fine organization,” Andrews told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, “and have a chance to win next year. We’ve had good talks with the Rangers.”

On Jan 15, 1982, the Rangers announced – at the team’s winter banquet – that they had agreed to terms with Johnson. He was penciled in as the team’s designated hitter, but Johnson hit just .259 with seven homers and 38 RBI in 105 games that year. The Rangers finished the year with a record of 64-98 as both manager Don Zimmer and general manager Eddie Robinson failed to complete the season in their initial roles.

Johnson’s final at-bat of the season came on Oct. 2 when he pinch-hit for Mike Richardt against the Angels. He grounded out to the pitcher to end the game, a victory that wrapped up the American League West title for California.

It was the last game of Johnson’s MLB career, which ended upon his retirement in 1983.

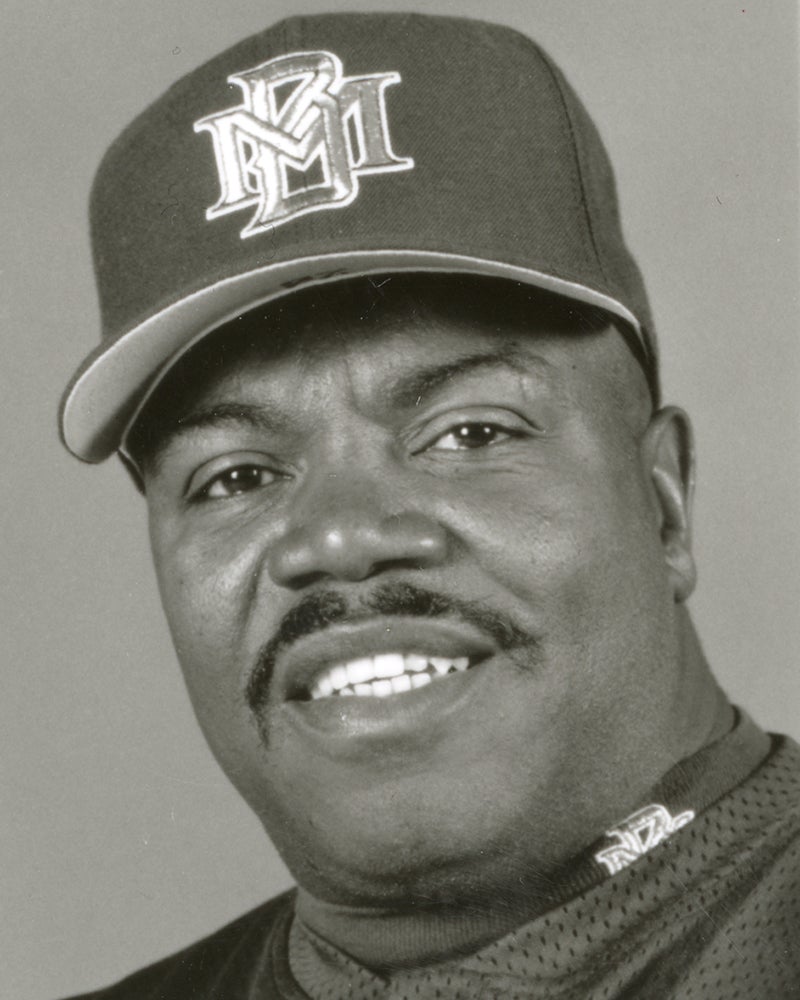

He spent two years in Texas in the real estate business before re-entering baseball by working at baseball camps and as a Little League coach. Then in 1988, Johnson joined the Brewers as a minor league hitting instructor. He managed Milwaukee’s Class A affiliate in Stockton, Calif., in 1993 and 1994 before becoming the Brewers’ big league hitting coach in 1995. He remained in that position until he was dismissed during the 1998 season but was soon hired by the Royals – managed by Tony Muser, who beat him out of a job in 1975 with the White Sox – as their hitting coach for 1999.

“He never gets very excited or panic-ridden when things aren’t going great,” Muser told the Kansas City Star about Johnson. “And he’s very stable when things are going well.

“Lamar has a very soft approach with the players. He can be tough on them when he has to be, but he communicates with them very well.”

Johnson remained with the Royals through 2002 then joined the Mariners as their hitting coach for the 2003 season. He went to work for the Mets as a minor league instructor in 2005, eventually serving as the team’s hitting coach in 2014 after Dave Hudgens was dismissed in May. Following that season, he returned to his role as a minor league instructor with the Mets.

“I enjoy working with hitters,” Johnson told the Kansas City Star. “It’s a thankless job. You don’t come in to get any credit for what you do. You get satisfaction out of going up there and seeing guys do things the right way and being successful. That’s what it’s all about.”

In nine big league seasons as a player, Johnson hit .287 with a .754 OPS, 122 doubles, 64 home runs and 381 RBI. He didn’t become a regular until he was 26 and was out of the big leagues before turned 33. But despite a short playing career, Johnson spent his professional life teaching something he could always do: Hit the ball.

“When I retired, I thought I’d get into something else,” Johnson told the Kansas City Star in 1999. “But everything started coming back to baseball.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum