#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Willie Aikens

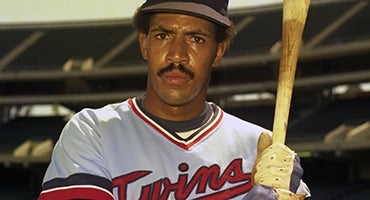

Willie Aikens was the talk of baseball in the fall of 1980 when he became just the eighth player in history to hit four home runs in one World Series.

Three years later, Aikens was arrested for attempting to purchase cocaine. And by the start of the 21st century, Aikens was incarcerated on a felony drug charge.

But while his eight-year big league career might have fallen short of expectations, his life story became one of redemption after his release from prison.

He was born Willie Mays Aikens on Oct. 14, 1954, in Seneca, S.C. – a little more than two weeks after Willie Mays robbed Vic Wertz with “The Catch” in Game 1 of the World Series.

“My mother named me for my uncle Willie,” Aikens told the Tampa Bay Times during the 1980 World Series. “I needed a middle name so the doctor who delivered me suggested ‘Mays’ since Willie Mays was the biggest sports hero in the whole wide world.”

Aikens grew into his 6-foot-3 frame and crushed amateur pitching with his left-handed swing despite batting weight issues that saw him tip the scales at more than 250 pounds. Undrafted out of high school, Aikens enrolled at South Carolina State University as both a football and baseball player after graduating from Seneca High School in 1972.

Aikens even got a look at an Orioles workout, impressing Baltimore manager Earl Weaver and then-Orioles coach (and Aikens’ future Royals manager) Jim Frey.

“He wasn’t just hitting them over the fence,” Weaver told the Los Angeles Times of that workout. “He was hitting them in the concrete stands.”

Soon after Aikens arrived, South Carolina State soon dropped its baseball program after opting to start a women’s basketball team in the wake of Title IX legislation, and Aikens found himself eligible for the 1975 January MLB Draft for collegiate players.

Gene Richards, another former South Carolina State player, went first in that draft to the San Diego Padres. Aikens was picked next by the California Angels.

A catcher in high school, Aikens was moved to first base and played the 1975 season for Quad Cities of the Class A Midwest League, hitting .284 with 17 homers and 91 RBI in 125 games. Then in 1976, Aikens thrust himself onto the lists of the game’s top prospects by hitting .317 with 30 home runs and 117 RBI for Double-A El Paso.

“Aikens is a tough out, and he’s a good hitter,” Amarillo Gold Sox manager Bob Miller, a veteran of 17 big league seasons as a relief pitcher, told the Amarillo Globe-Times after Aikens hit two home runs in one game against his team in July of 1976. “He’s so strong. He just doesn’t seem to have many weaknesses.

“One mistake to him, and the game’s over.”

Amarillo won the Texas League title that year, and Aikens was named the All-Texas League first baseman.

The Angels brought Aikens to their big league camp in the spring of 1977, and Aikens made headlines across the nation thanks to his name and his propensity to hit baseballs a long way. But Angels owner Gene Autry was in the midst of a spending spree that saw him bring veterans like Don Baylor, Bobby Grich and Joe Rudi to Southern California, and Aikens was sent to Triple-A Salt Lake City to begin the season.

After punishing minor league pitching, Aikens was called up to the Angels in May. He made his big league debut on May 17, going 1-for-3 with two runs scored as the Angels’ designated hitter against the Red Sox. But Aikens cooled off after a hot start and was soon relegated to a pinch-hitting role before being sent back to Salt Lake City in July.

“We have plenty of outstanding young talent in the minor league system,” Aikens told the Salt Lake Tribune in late August, “and they should get a chance.”

Aikens was recalled to the Angels in September and finished the year hitting .198 in 42 games with California while failing to produce a home run. But in 77 games with Salt Lake City that year, Aikens hit .336 with 23 doubles, 14 homers and 73 RBI. Meanwhile, he began work on tackling a lifelong stuttering issue by seeking help from speech therapists.

Aikens hit well in Spring Training of 1978 but found himself back in the minors as the Angels continued to stock up on veterans, this time adding outfielders Lyman Bostock and Rick Miller in the offseason while featuring a deep first base position that featured Ron Fairly, Tony Solaita and Ron Jackson. Aikens spent the entire season in Triple-A, leading the Pacific Coast League with 29 homers while batting .326 with a .419 on-base percentage and 110 RBI in 133 games.

Coming off that campaign, Aikens appeared to be poised to challenge for the Angels’ first base job. But on Feb. 3, 1979, California swung a deal for seven-time American League batting champion Rod Carew – sending four prospects to the Twins and blocking Aikens’ path at first base.

Aikens was playing for Ciudad Obregon of the Mexican Pacific Winter League when he learned of the potential trade, which was rumored for days before it was completed.

“There wasn’t anything I could do about it,” Aikens told the Desert Sun of Palm Springs, Calif., during Spring Training of 1979. “So I told myself: ‘Come to Spring Training ready and do what you have to do to stick on the team…show what I can do in the big leagues.’”

Aikens made the Angels’ Opening Day roster in 1979 but didn’t appear in a game until April 11 following Dan Ford’s knee injury. Penciled in at designated hitter by manager Jim Fregosi, Aikens totaled two doubles, two homers and seven RBI in his first three contests. He was hitting .328 at the end of April and later spent much of June and July at first base when Carew was injured.

Aikens finished the season with a .280 batting average, 21 homers and 81 RBI in 116 games as the Angels won their first American League West title. But he did not appear in the team’s ALCS loss to the Orioles after suffering a late-season knee injury. And on Dec. 6, 1979, the Angels traded Aikens and Rance Mulliniks to the Royals in exchange for Al Cowens, Todd Cruz and a player-to-be-named later who turned out to be pitcher Craig Eaton.

“I’ve known Aikens since he was a kid,” new Royals manager Jim Frey told the Wichita Eagle. “And everyone told me he can’t hit the breaking stuff or the changeup. I saw him do it in 1979.”

The Royals immediately penciled in Aikens at first base, convinced they had found the missing piece for a team that had won three straight AL West titles from 1976-78 but failed to reach the World Series.

“He’s one of the best young power hitters to come along in some time,” Royals scouting director John Schuerholz told the Wichita Eagle.

Aikens delivered as promised, hitting .278 with 20 homers and 98 RBI as the Royals reclaimed the AL West title. And he did it in a home ballpark – Royals Stadium – that was famous for its mammoth dimensions.

“Royals Stadium is the toughest park I’ve seen for a home run hitter,” Aikens said during the 1980 World Series. “For a while, it psyched me out. I kept hitting long fly balls. Fans began to get on me, to boo.”

But those boos turned to cheers in the postseason. Aikens hit .364 with two RBI in the Royals’ sweep of the Yankees in the ALCS. Then in the World Series, Aikens blasted two homers in Game 1 against the Phillies and another two home runs in Game 4 – becoming just the fifth player in history with at least two multiple-homer games in the World Series.

The Phillies issued Aikens two walks apiece in both Game 5 and Game 6, winning both contests to take the title. But Aikens was now a national celebrity.

“I had a good (World Series),” Aikens told the Anderson Independent in the spring of 1981. “But that’s something I can forget about now. That’s not going to help me this year.

“I have to prove this season that I can be a complete player – not only to Kansas City, but to myself.”

Aikens had a solid campaign in 1981, hitting 17 home runs and driving in 53 runs in that strike-shortened season. He also walked 62 times against only 47 strikeouts, compiling a .377 on-base percentage. Aikens had three hits and three walks in the ALDS vs. Oakland, which the A’s swept in three games.

Arbitration-eligible for the first time, Aikens was awarded a salary of $350,000 for 1982 when an arbitrator chose his figure over the $250,000 offered by the Royals. It marked the first time in club history a player had won an arbitration case against the Royals.

“Obviously, the arbitrator recognized that Willie has been one of the most consistent sluggers in the game over the last three years,” Aikens’ agent Ron Shapiro told the Kansas City Star.

Aikens had a productive year in 1982, batting .281 with 29 doubles, 17 homers and 74 RBI in 134 games. But in 1983, his lifepath changed dramatically.

Aikens had little trouble at the plate that year but missed time with nagging injuries and feuded with Royals manager Dick Howser when he was platooned at first base. Then in August, Aikens was cited in a federal drug probe along with Royals teammates Willie Wilson, Vida Blue and Jerry Martin. Aikens pleaded guilty in October to a misdemeanor charge of attempted cocaine possession and was sentenced to three months in jail.

On Dec. 15, 1983, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn suspended Aikens, Wilson and Martin for one year.

“I think there’s a message to today’s decision: We take the drug problem seriously,” Kuhn told United Press International.

Five days after Kuhn’s decision, Aikens was traded to the Blue Jays for Jorge Orta.

“One thing drugs can do to you is change your whole attitude toward the team and everything else,” Aikens told the Canadian Press while in a rehabilitation clinic following the trade. “There were times I didn’t care whether we won or lost. It got to the point where I became an addict.”

Aikens’ numbers in 1983, however, proved he could still play. He hit .302 with 23 homers and 72 RBI in 125 games. And with MLB promising to re-evaluate the one-year suspension in May of 1984, the Blue Jays decided to sign Aikens to a two-year deal.

Aikens served 81 days in prison and sat out the first month and a half of the 1984 season before MLB reinstated him on May 15. He appeared as a pinch hitter a day later and was in the Blue Jays’ starting lineup as the DH on May 17 – but he was unable to get untracked at the plate, finishing the year hitting .205 with 11 home runs and 26 RBI in 93 games.

When Aikens hit .200 in 12 games in April in 1985, the Blue Jays had seen enough. They released Aikens and his $600,000 salary on May 9 before bringing him back on a minor league deal and assigning him to Triple-A Syracuse 10 days later. He hit .311 with 16 homers and a .416 on-base percentage in 105 games in Triple-A but was not recalled to Toronto as the Blue Jays won their first AL East title before losing to the Royals in the ALCS.

Finding few opportunities in the majors, Aikens returned to Mexico for parts of the next six years. Then in 1994, Aikens was arrested for selling crack cocaine to an undercover officer. Sentenced to jail again, he spent 14 years in prison before being released in 2008.

But even at his darkest hour, Aikens had the support of many of his teammates.

“Willie is a genuinely good person,” former teammate John Wathan told the Kansas City Star in 1994. “Everybody on the team liked him. He gave us a lot of big games.”

After his release from prison, Aikens coached in the Royals’ minor league system for nine years and eventually joined the Royals’ front office. In 2022, the movie “The Royal” debuted, depicting Aikens’ battle to stay clean.

“I’m hoping that this film will show that if you do time in prison, that it’s not the end of the line,” Aikens told an audience at the Hall of Fame during a screening of the film. “I’m hoping that this movie will show that if you do an inventory of your life during the period of time when you are incarcerated, you can become a better person and get out of prison and make good decisions.”

Aikens finished his big league career with a .271 batting average, a .354 on-base percentage, 110 home runs and 125 doubles. His postseason exploits, his battle to overcome addiction and a name that will always be linked to greatness has kept him in the baseball consciousness for decades.

“I’m not at all ashamed to be named Willie Mays Aikens, but I do wish the announcers would call me just ‘Willie Aikens,’” Aikens told the Tampa Bay Times during the 1980 World Series. “I mean, they don’t announce (Royals teammate George) Brett as ‘George Howard Brett’.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum