- Home

- Our Stories

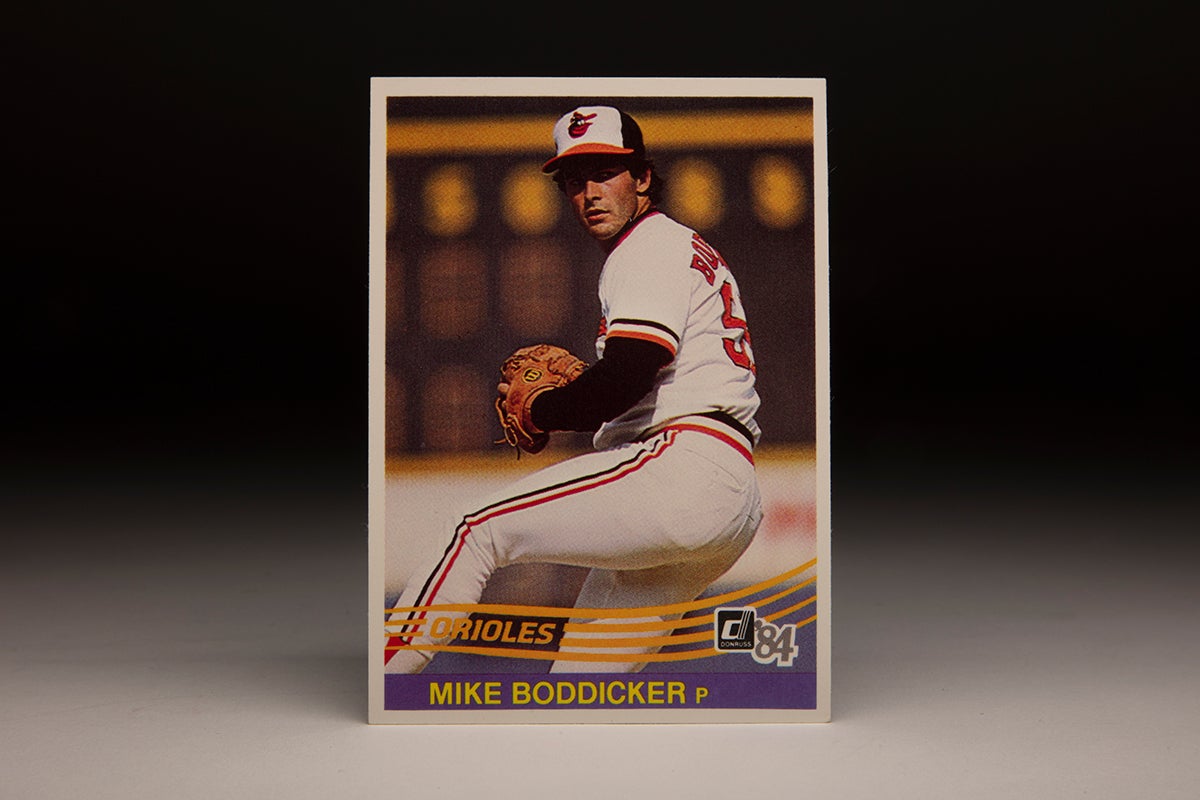

- #CardCorner: 1984 Donruss Mike Boddicker

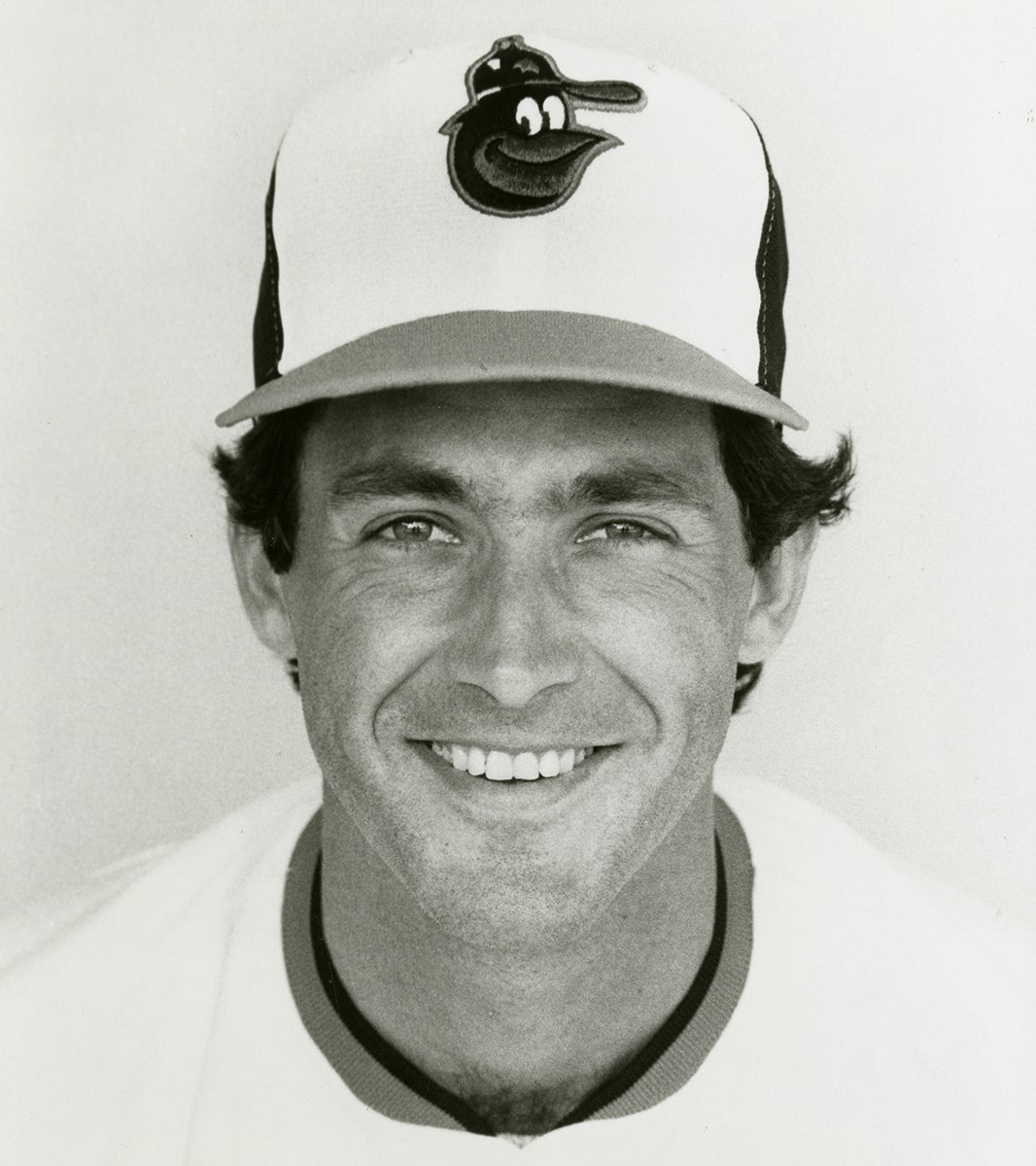

#CardCorner: 1984 Donruss Mike Boddicker

He burst on the big league scene like few pitchers before or since, allowing zero earned runs in his two postseason games in his rookie year while helping Baltimore win the World Series.

Today, Mike Boddicker – whose fastball never lit up radar guns – might not even get a second look by scouts. But using control, change-of-pace and an off-speed pitch known as a foshball, Boddicker became a bona fide star.

Born Aug. 23, 1957, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Boddicker was raised in nearby Norway – a town listed in the 2020 census as having fewer than 500 residents. The youngest of five children, Boddicker came of age in a baseball-crazy town that regularly produced state championships in Iowa’s smallest high school division.

“That’s all we do in Norway is play baseball,” Boddicker told the Memphis Press-Scimitar in 1983. “Nothing else to do. We played it every hour we could when I was growing up.”

Boddicker set Iowa state high school records with 1,122 strikeouts and 76 wins and was also a fine hitter. The Expos selected him in the eighth round of the 1975 MLB Draft but Boddicker opted for college and enrolled at the University of Iowa, where he continued as a two-way player on the mound and at third base. In his freshman season of 1976, he was named a finalist for the Lefty Gomez Plate Award given to the national collegiate player of the year.

Boddicker later pitched for the powerhouse Fairbanks, Alaska, team in summer league action and was taken by the Orioles in the sixth round of the 1978 MLB Draft. Boddicker agreed to a contract and was sent to Bluefield of the Appalachian League, where he dominated much younger hitters before being promoted to Double-A Charlotte and then Triple-A Rochester – finishing the year with a 7-4 record and 1.62 ERA in 89 innings.

Following most of his minor league seasons, Boddicker went home to Norway and worked the second shift at Pollock Elevators, unloading and drying corn from 5 p.m. to 2 a.m.

“Mike’s the type of lad who would make a go of whatever profession he tackled,” Jerry Pollock, the owner of Pollock Elevators, told the Cedar Rapids Gazette during the 1983 postseason when Boddicker was pitching the Orioles to a World Series title. “I don’t care if he tried out to be a chiropractor, a medical doctor or a baseball player.

“Mike’s got plenty of ambition and desire and that’s how you get to Carnegie Hall. You practice, practice, practice.”

In 1979, Boddicker started the season with Charlotte, going 9-3 before earning another promotion to Rochester. He struggled for the first time as a professional at Triple-A, going 4-6 with a 6.00 ERA to finish the season 13-9 over 174 innings. He was not part of the Orioles’ big league roster in the spring of 1980 but was much better in his return to Rochester, starting out 3-7 before finishing 12-9 with three shutouts and a 2.18 ERA. He also pitched a complete game against the Orioles in an exhibition outing in July, striking out six in a 9-3 Rochester win.

On Sept. 5, Boddicker joined an Orioles team in the stretch run of a terrific battle with the Yankees for the American League East title.

“I met with (Orioles manager Earl) Weaver when I arrived in Baltimore,” Boddicker told the Cedar Rapids Gazette. “He was honest with me. He said I might pitch a lot, or I might not pitch at all. But he also said to be ready any time. Mr. Weaver just wants me to get my feet on the ground and get a taste of things.”

Boddicker did not see any action for a month as Weaver relied on veteran starters Jim Palmer, Mike Flanagan, Steve Stone and Scott McGregor. But when the Yankees defeated Detroit on the afternoon of Oct. 4 in the first game of a doubleheader, the Orioles were eliminated. Boddicker then drew his first big league start that evening, allowing six runs over 7.1 innings in a 6-4 loss to Cleveland.

“I didn’t think I had a chance in the world of making it to Baltimore this year,” Boddicker told the Gazette. “It just didn’t seem possible.”

But his rapid ascension to the majors did not translate into a regular big league job. Weaver continued to lean on his veterans the next two seasons, with Boddicker going 10-10 with a 4.20 ERA for Rochester in 1981 and then returning to Western New York the following year to go 10-5 with a 3.58 ERA. He made a handful of appearances both seasons with the Orioles but was still blocked in the spring of 1983 and started the year in Rochester, making an appearance with the Red Wings for the sixth consecutive season.

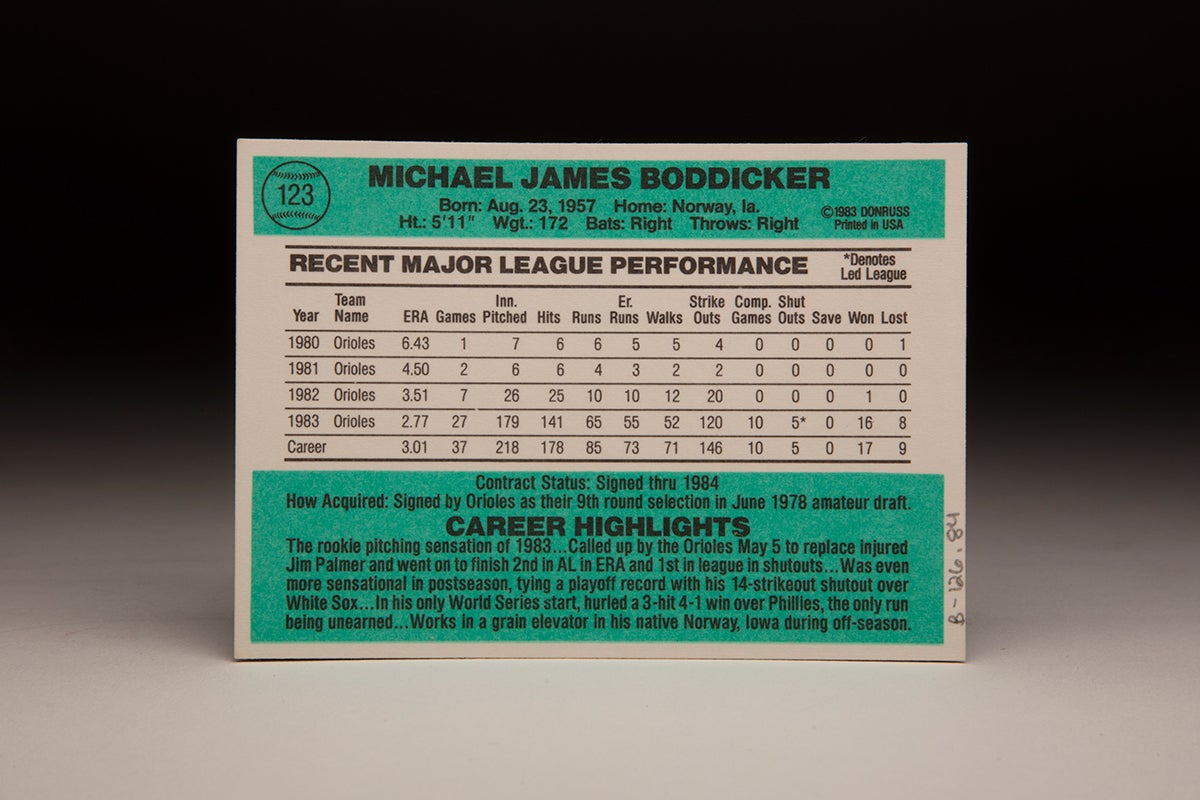

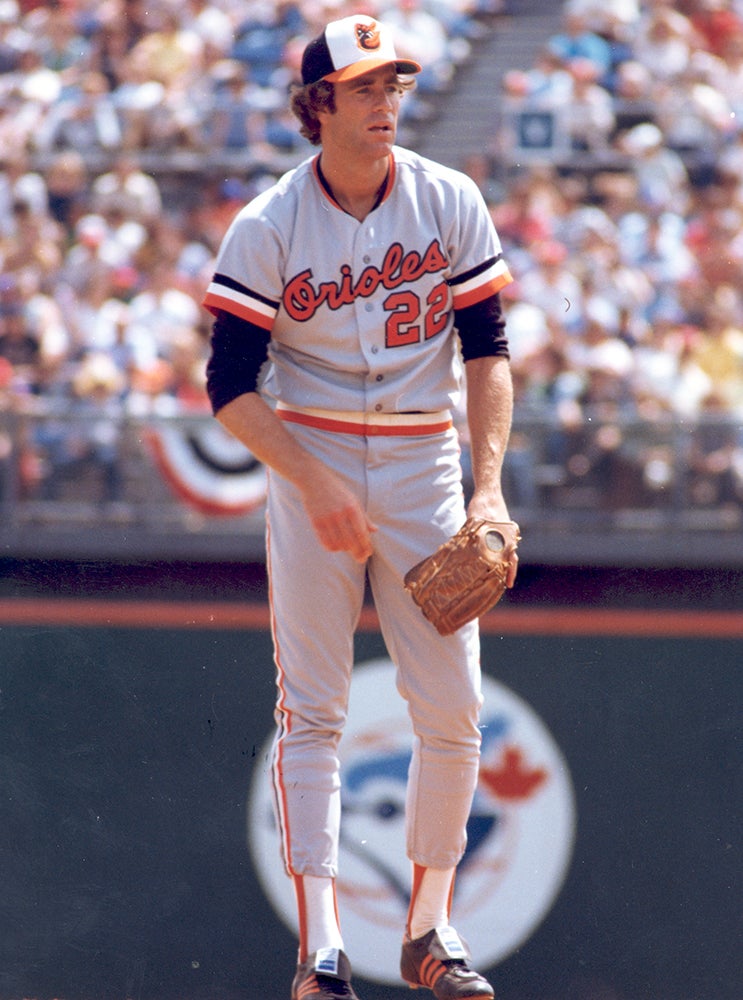

But on May 17, Flanagan injured his left knee while fielding a slow roller by the White Sox’s Tony Bernazard. The damaged ligament landed Flanagan, who was 6-0 at that time, on the disabled list and prompted the Orioles to put Boddicker, who was already with the big league team, into the starting rotation. Boddicker shut out the White Sox on five hits in the second game of the May 17 doubleheader against Chicago, threw another shutout against Seattle on July 10 and caught fire down the stretch, going 16-8 with a 2.77 ERA and an MLB-best five shutouts over 179 innings.

The Orioles won the AL East under new manager Joe Altobelli, and the baseball world was enthralled by Boddicker’s “foshball” – a hybrid forkball/change-up that broke down and in to right-handed batters like a screwball and was just as effective against lefties.

“Things looked a little grim for me in ’81, when I didn’t get a shot in the spring after the year I had in ’80,” Boddicker told the Baltimore Sun on July 31, 1983, when he pitched a four-hit shutout over the Rangers on the same day Baltimore legend Brooks Robinson was inducted into the Hall of Fame as part of the Class of 1983. “I went back to Rochester in 1981 and had a horrible stretch. It made me start to wonder.

“I still have a little doubt about what will happen to me.”

But Boddicker needn't have worried. Altobelli tabbed him to start Game 2 of the ALCS vs. the White Sox – which became virtually a must-win after Chicago won Game 1 of the best-of-5 series 2-1. Boddicker struck out 14 batters in a complete game 4-0 victory, fanning Julio Cruz with the bases loaded to end the game.

“I was a little nervous, sure,” Boddicker told The Boston Globe. “I got ready the way I always got ready: Put a CB radio into my pickup, played a video game, just like I did during the season.”

The performance in that single game earned Boddicker the ALCS Most Valuable Player honors.

“Not bad for a kid from Norway, Iowa,” Altobelli said.

The Orioles won the next two games to clinch the series, setting up Boddicker to pitch Game 2 of the World Series against the Phillies. Once again, Baltimore lost Game 1. And once again, Boddicker was brilliant in Game 2, striking out six and allowing just three hits over nine innings.

“I’ve always pitched like that,” Boddicker told the Press-Scimitar after holding the Phillies to one unearned run in a 4-1 Game 2 victory that evened the World Series and propelled Baltimore to the title. “It’s just this year that I learned to change speeds that well, but I always threw a lot of curves and sliders.

“It’s fun watching guys go back to the dugout and curse and throw their bats.”

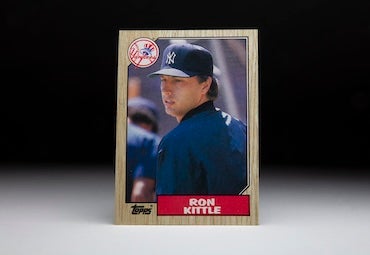

Now a full-blown media sensation, Boddicker finished third in the AL Rookie of the Year voting despite a Wins Above Replacement figure (4.1) that dwarfed those of winner Ron Kittle (1.9) and runner-up Julio Franco (0.9).

Norway, Iowa, declared Nov. 4, 1983, as “Mike Boddicker Day” and celebrated their favorite son with a dinner at the town community center that attracted nearly half the residents.

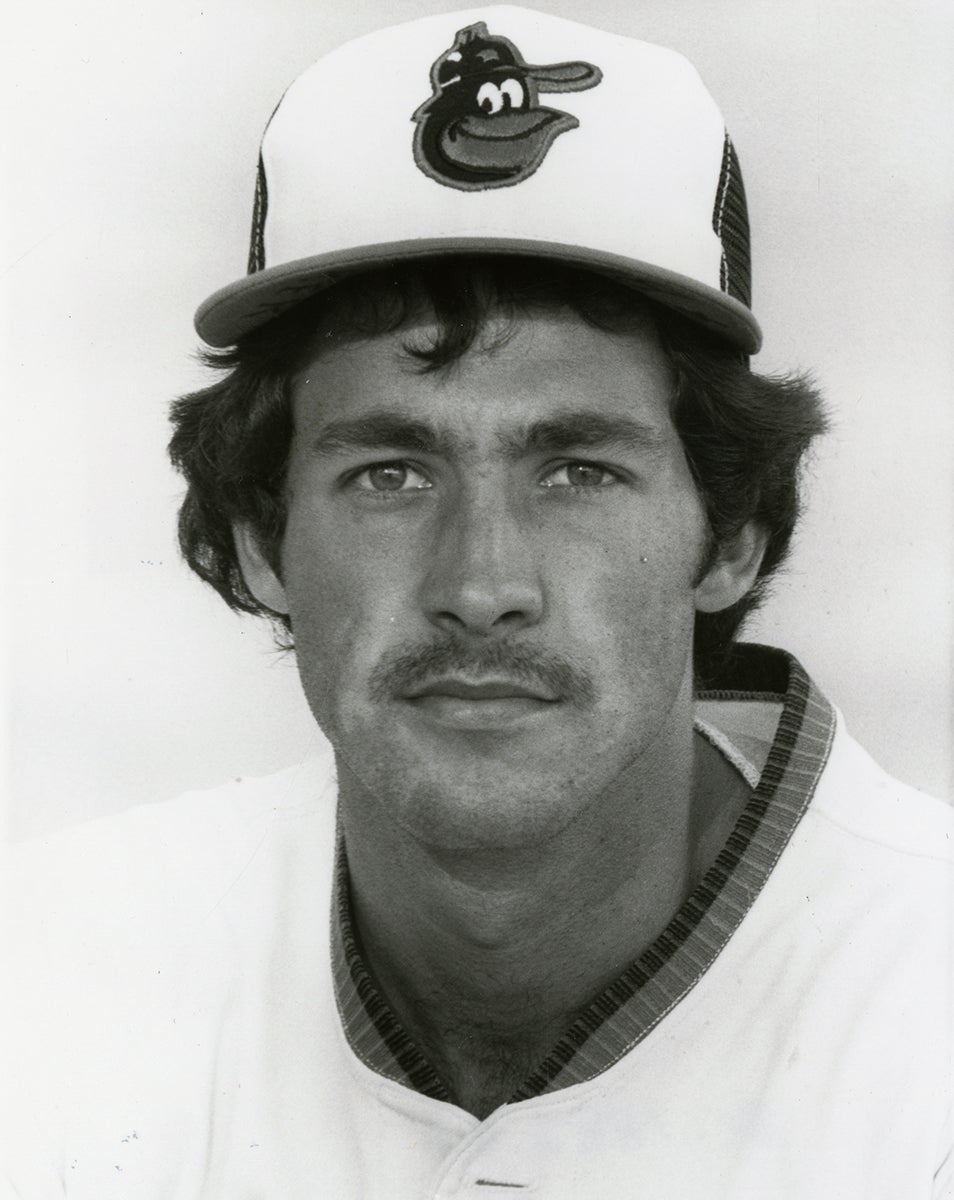

Boddicker had what would be his best big league regular season in 1984, going 20-11 with a 2.79 ERA over 261.1 innings, with both the wins total and ERA the best figures in the American League. Remarkably, he finished fourth in the AL Cy Young Award voting that year as two relievers – Detroit’s Willie Hernández and Kansas City’s Dan Quisenberry – finished first and second with Cleveland’s Bert Blyleven taking third-place honors.

Boddicker signed a two-year, $1.4 million contract in February of 1985 even though he was not yet eligible for arbitration. But Boddicker and the Orioles struggled that season as Altobelli lost his job, Weaver returned as manager and Boddicker went 12-17 with a 4.07 ERA. The aging Orioles were unable to capture the magic of 1983 during the next two seasons, as Boddicker went 14-12 with a 4.70 ERA in 1986 and 10-12 with a 4.18 ERA in 1987.

Heading into what would be his contract year in 1988, Boddicker seemed to be a prime trade candidate. Baltimore began the season with a record 21 straight losses.

“It was pretty discouraging,” Boddicker told the Daily Hampshire Gazette in 1989. “You know you aren’t going to win every game, but you want to win, and losing (21) in a row, being out of the pennant race after only a month was hard to handle.”

Boddicker was 6-12 with a 3.86 ERA on July 29 when the Orioles sent him to Boston in a deal that returned Brady Anderson and Curt Schilling. Boddicker quickly agreed to a two-year contract extension with the Red Sox worth a reported $2.05 million.

“I like Anderson an awful lot,” Red Sox manager Joe Morgan told the Associated Press. “But it’s the same old story: You have to give up something to get something.

“This guy (Boddicker) can mean the difference for us.”

Enmeshed in a three-play race with the Tigers and Yankees for the AL East title, the Red Sox got hot down the stretch as Boddicker went 7-3 with a 2.63 ERA over 15 outings. Boston won the AL East title, and Boddicker drew the start in Game 3 of the ALCS vs. Oakland. But unlike 1983, Boddicker was ineffective – allowing six runs over 2.2 innings in what would become a 10-6 loss.

The Athletics swept the series in four games.

Boddicker was a workhorse for the Red Sox the next two years, going 15-11 with a 4.00 ERA in 1989 and then 17-8 with a 3.36 ERA in 1990 as Boston returned to the top of the AL East standings. He fared much better in the ALCS vs. Oakland this time around, pitching a complete game while allowing four runs (two earned) in a hard-luck 4-1 loss in Game 3.

Once again, Oakland swept the series.

Boddicker won a Gold Glove Award following the season and tested the free agent waters for the first time in his career. The Red Sox pushed to re-sign him but in the end Boddicker chose to be closer to his Iowa home, signing a three-year deal with the Royals worth a reported $9 million.

“At first, I couldn’t believe the Royals would be interested,” Boddicker told the Associated Press. “They have such great pitching here. It didn’t take long for me to make up my mind.”

But seven straight 200-plus inning seasons had already taken a toll on the 5-foot-11 Boddicker, and he dropped to 180.2 innings pitched in 1991 while going 12-12 with a 4.08 ERA. He was demoted to the bullpen in 1992 and finished 1-4 with a 4.98 ERA in 86.2 innings before the Royals sold his contract to the Brewers on April 26, 1993, without Boddicker having appeared in a game to that point.

He went 3-5 with a 5.67 ERA in 10 starts for Milwaukee while battling a sore knee that resulted in a stint on the disabled list. On July 15, 1993, Boddicker announced his retirement.

Over 14 big league seasons, Boddicker was 134-116 with a 3.80 ERA and 1,330 strikeouts in 2,123.2 innings. Few pitchers knew the heights that Boddicker ascended in 1983 – and even fewer likely got more out of their natural ability.

“If I were a pitcher, that’s how I’d pitch,” Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt told the Press-Scimitar about Boddicker during the 1983 World Series. “I’d have a couple of different curveballs with a couple of different breaks and speeds on each of them.

“Most pitchers I see in the National League rely on the fastball, but he can show you a curveball at any time.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum