- Home

- Our Stories

- Century Season: Rogers Hornsby's 1925 Triple Crown

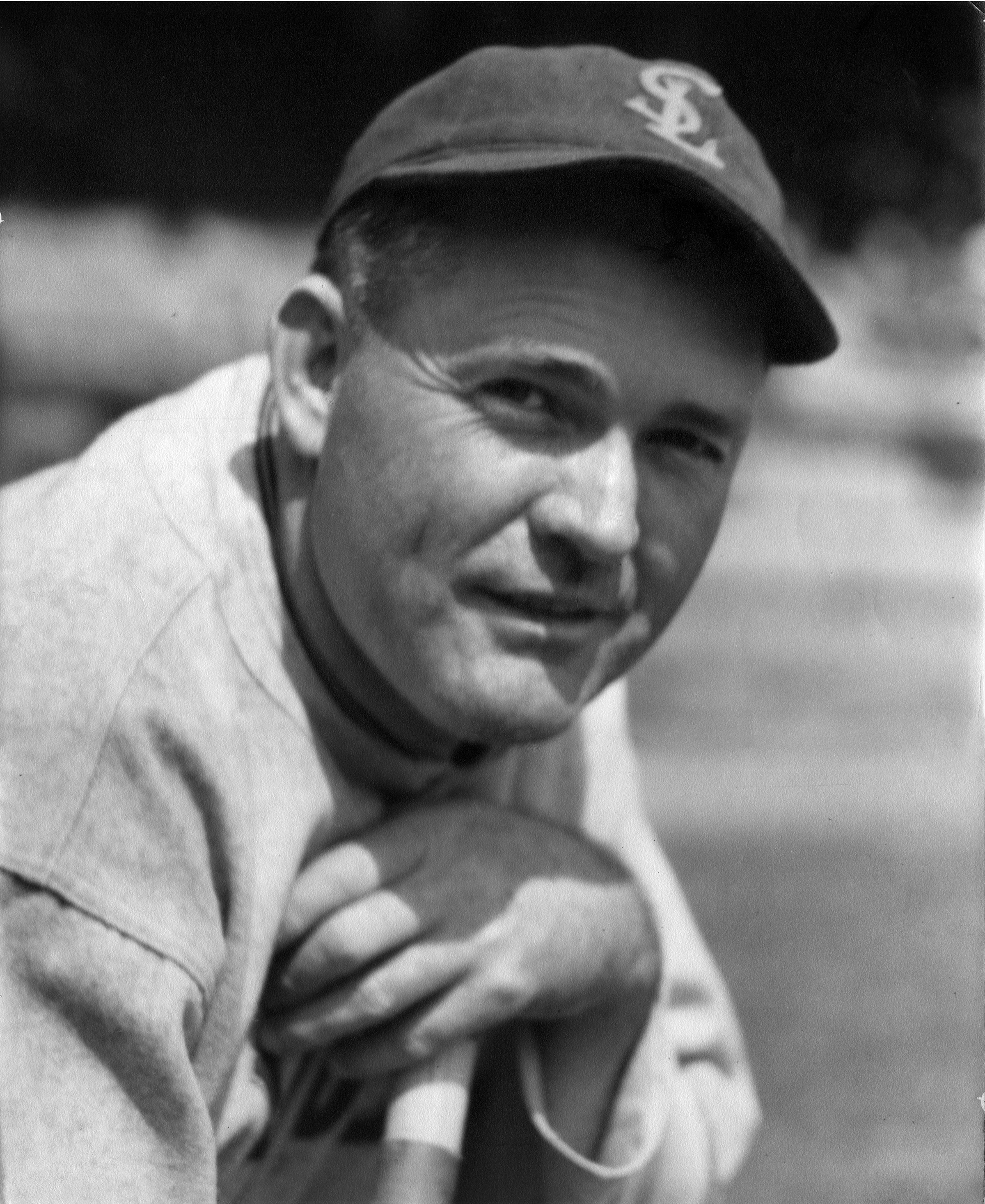

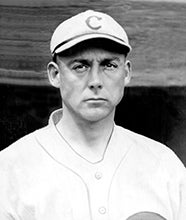

Century Season: Rogers Hornsby's 1925 Triple Crown

Today, Rogers Hornsby is known by baseball fans as arguably the greatest right-handed hitter in major league history. But a century ago, the “Rajah of Swat” was considered by many as the best hitter of any kind after putting the finishing touches on one of the more remarkable multi-year stretches of batting prowess in history.

The star second baseman, in the five campaigns from 1921 through ‘25, averaged an amazing .402. One-hundred years ago, in his 1925 Triple Crown season in which he was then a player/manager with the St. Louis Cardinals, he led the National League by batting .403 (his record-tying third season hitting .400) with 39 home runs and 143 RBI and would capture his first of two NL Most Valuable Players Awards. He passed the .400 threshold in ‘25 by getting 10 hits in his last four games of the season.

Prior to the start of the 1925 campaign, veteran submarine hurler Carl Mays of the Cincinnati Reds told Baseball Magazine that he regarded Hornsby the game’s greatest batsman.

“I have faced Ty Cobb at bat plenty of times, and I have faced George Sisler, Tris Speaker and Eddie Collins,” said Mays, against whom Hornsby hit .412 (14-for-34). “I was on the same ballclub for years with Babe Ruth, and I know what those fellows can do and what they can’t do. They are a great bunch of hitters.

“But there isn’t one in the bunch who can shake hands on an equality with Rogers Hornsby when it comes to plain, unadulterated batting ability. He’s the greatest hitter I ever saw.”

One year after hitting .424 in 1924 – the highest NL/AL single-season average of the Modern Era (post 1900) – Hornsby’s ‘25 batting average of .403 came via an astonishing .478 mark at the Cardinals’ home, Sportsman’s Park. And to prove the vagaries of hitting, even for a legend like Hornsby, he hit safeties at a .480 clip in June and followed it up a month later with a .326 mark in July.

“I faced those same pitchers earlier in the season and later and socked them good and plenty,” said Hornsby after the 1925 season, explaining his batting “slump” in July. “But you know a fellow can’t get a base hit with each swing and I guess that was the way it was with me during the road trip in July.”

Though Hornsby’s consistency was masterful, failing to get a hit in only 27 of his 138 games played in 1925; in 19 games versus the Reds, he batted his lowest against any team at .299.

“Roush’s outfielding against me is one of the phenomenons of my batting career,” explained Hornsby, referring to Hall of Famer Edd Roush. “I don’t know what psychic spell Eddie holds over me, but he plays me different than any other center fielder in the league.

“He will move over towards right and then again he will play towards left – always deep – and I have seen one long drive after another sail right to him. It doesn’t make much difference where he is – if it’s towards right, my drive goes to him. It is the same when he moves over towards left. I don’t think I have ever hit a ball over Eddie Roush’s head. I don’t think I am exaggerating when I say that Roush, through his remarkable fielding, steals at least 10 hits in a season from me. Maybe more. Give me 10 more hits and you will see I am in the .400 class against the Reds.”

It was Hornsby’s altruistic devotion to baseball that, in the minds of many, made him the celebrated player he ultimately became. One famous quote in particular, attributed to him, may sum up his mental attitude the best: “People ask me what I do in winter when there’s no baseball. I’ll tell you what I do. I stare out the window and wait for spring.”

“Health is important in any line of work. But it is absolutely essential in baseball,” he said in 1925. “When the season is on, I think of nothing but baseball. I eat it and sleep it and have my mind concentrated on the subject. I do not smoke nor use tobacco in any form. Nor do I drink. Fortunately for me, I have never taken up any of those habits. I do not criticize them in others, and I admit they may not be serious impairments to condition. But none of these things help an athlete any and I am glad I let them alone. I also keep regular hours and manage to get my assignment of sleep every night.”

Hoping to not impair his eyesight, it was reported that Hornsby during his playing days avoided going to the movies and never read on moving trains.

“This was a small price,” explained Hornsby to Baseball Digest in 1951. “I wanted to be a ballplayer, and I wanted to make myself as outstanding as I possibly could. Baseball is the greatest game. It offers every opportunity to an American boy.

“I worked hard to get ahead and I perfected myself. But some of the fellows now playing ball ought to pay their way into the park, for the amount of effort they put into their careers. I got myself out at the park at 10 in the morning. No one ever told me to show up that early. I just did it. Pride in my work, I guess.”

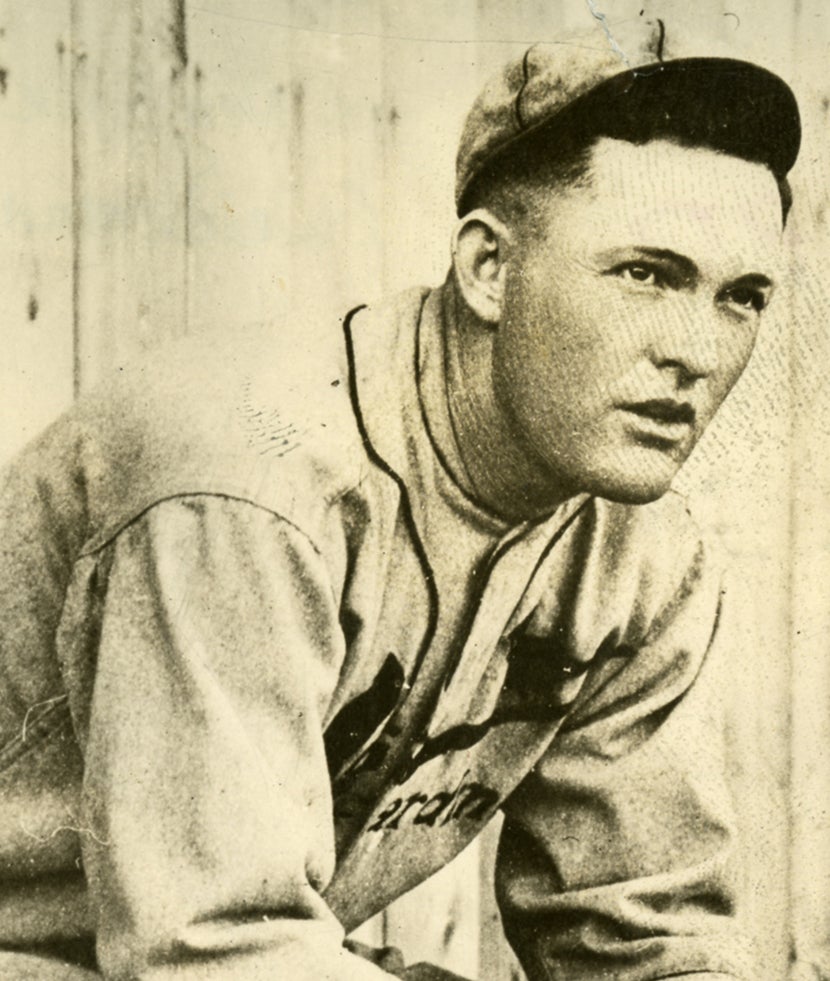

Former teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland Alexander saw the evolution of Hornsby from the mound.

“The first time I faced Rogers Hornsby I thought to myself I had never seen a batter who looked less formidable. I really pitied him,” Alexander recalled. “So, I laid one over the plate for him and he came through with a safe smash. Since that time, I haven’t been able to get him out. He’s hit me continuously; hit everything I had and seems to thrive on my pitching.

“Hornsby is the perfect hitter. He can hit anything and hit it hard. There’s none of this bunting, rapping out little grounders and that kind of stuff about Hornsby. He hits curves, slowballs, fastballs, any old kind of balls for good, solid smashes. He’s the most dangerous batter I ever faced.”

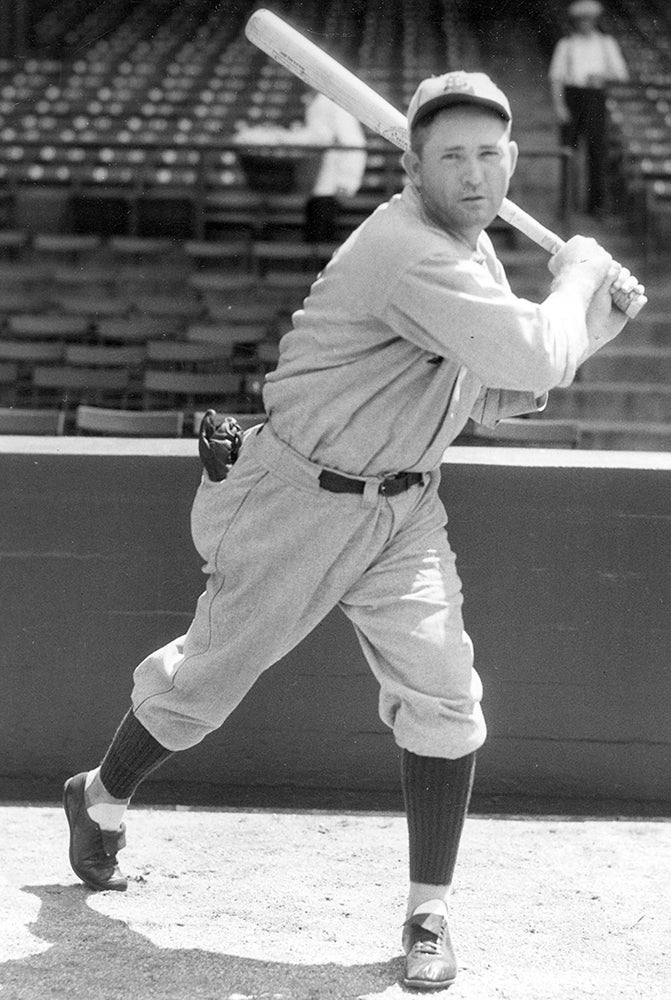

Hornsby explained, in a March 1925 piece in the Brooklyn Citizen, that he stood as far away from the plate as possible. Back at the extreme far corner of the batting box, he takes his stance and waits for the pitcher to let go.

“From this position, I can judge whether it is going inside or outside of the plate. There is no ducking if it is inside, as I’m not hugging the plate,” he explained. “I use a long bat, and when one comes over any part of the plate, I can get to it. If it’s on the far side, I step in and reach it. If it cuts the inside, I can stand still, and still swing fully, to hit it with the big end of the bat.

“From my position in the box, a low curve loses its baffling ability, and all pitches look the same. If they get over the plate between the knee and shoulder that’s a strike – and I hit them when they’re over.”

Ty Cobb, like Hornsby the only AL/NL hitter in the Modern Era to have three seasons of batting at least .400, marveled at his fellow Hall of Famer’s artistry at the plate.

“He stands well back from the plate and steps into the ball. He can meet the ball with equal ease either on the inside or the outside, high or low. His position at the plate is perfect,” Cobb said. “And with it all he has an easy, forceful swing, without an atom of wasted motion, which makes a powerful drive. Yes, Hornsby is the greatest natural batter I ever saw.”

Prior to the start of the 1925 season, on Feb. 7, Hornsby signed a three-year contract that called for a reported $100,000.

“Professional baseball is a business and, just like any other business, success in it is entirely up to the individual,” he told a reporter in July. “If a young man who can play baseball enters the professional field, buckles down and works hard, he is going to make a success of it. If he doesn’t, he probably wouldn’t be successful in anything else, unless he adopted different tactics.

“Professional baseball is not only a business,” he added, “it’s also a decided pleasure to anyone who plays it. When the salary question comes up, it’s a business, of course. But even the fact that professional ballplayers are paid for playing doesn’t detract from the fun of the thing. It’s still sport, just like golf or any other thing of that sort.”

The 1925 campaign was not without some hiccups for Hornsby along the way. On June 16, Hornsby and Phillies manager Art Fletcher came to blows in the sixth inning and were separated by players and police. Hornsby was fined $100 but not suspended.

National League President John Heydler said that in not imposing a suspension he had kept in mind Hornsby’s previous excellent record for peacefulness, as the heat of the day was not inducive to good temper.

“It was an extremely hot day, and the players were naturally not themselves,” Heydler said. “Fletcher himself is not held blameless, and I have fined him $50 for provoking the outbreak.”

But Hornsby was suspended for three days in August as a result of arguing about strikes with home plate umpire Monroe Sweeney.

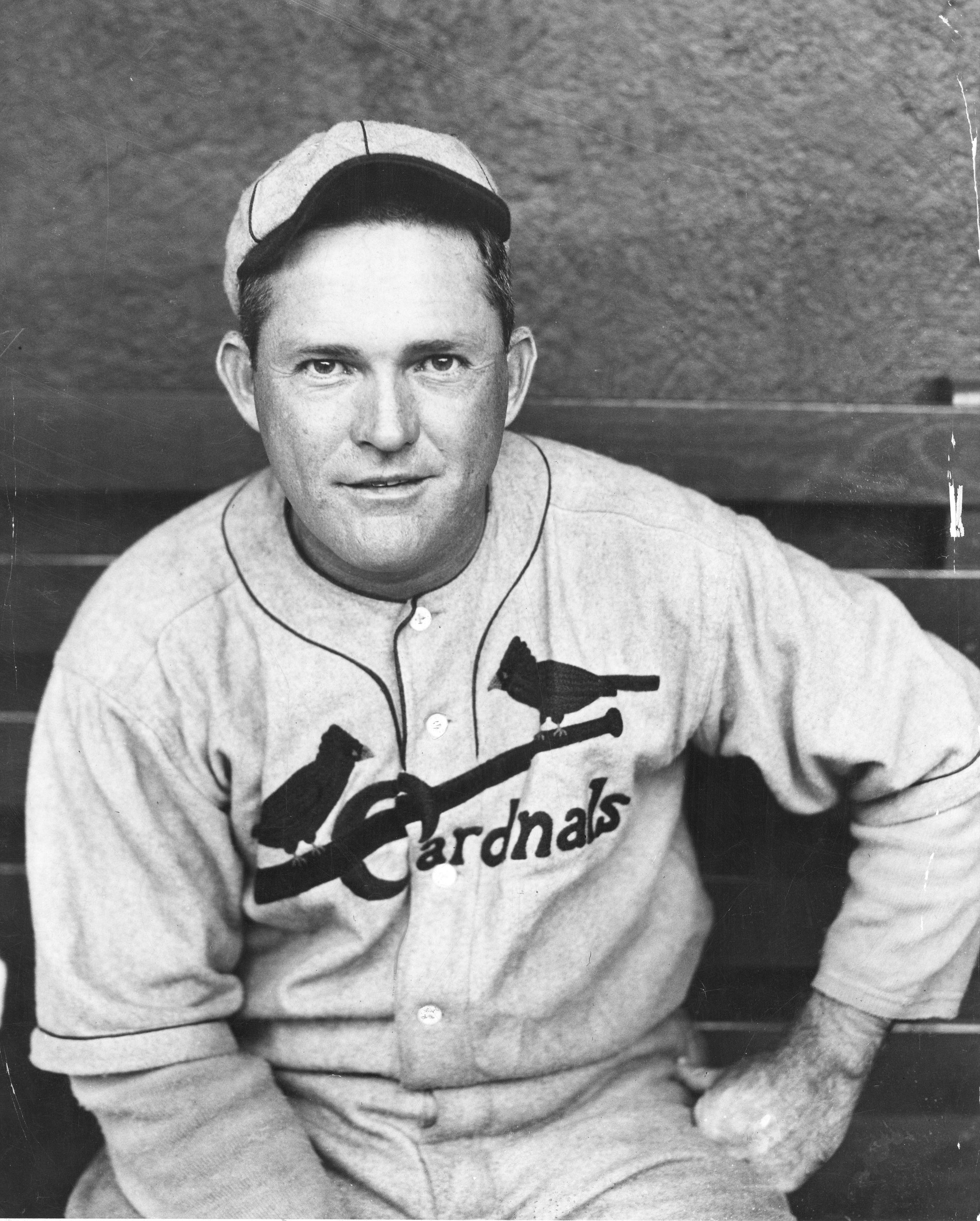

The 29-year-old Hornsby added to his responsibilities when he took over the Cardinals as player-manager on May 30, 1925. He succeeded Branch Rickey, who was made vice president of the club.

“We have been disappointed over the failure of the Cardinals to make a better showing this year,” said Cardinals owner Sam Breadon, referring to the franchise’s 13-25 record at the time of the change. “We decided Rickey was trying to do too much. He was trying to manage the team on the field and look after the vast organization of a major league club. We decided that we would have two men for two men’s work.

“Hornsby is a great player and will make a great manager. I expect him to put new fight into the Cardinals.”

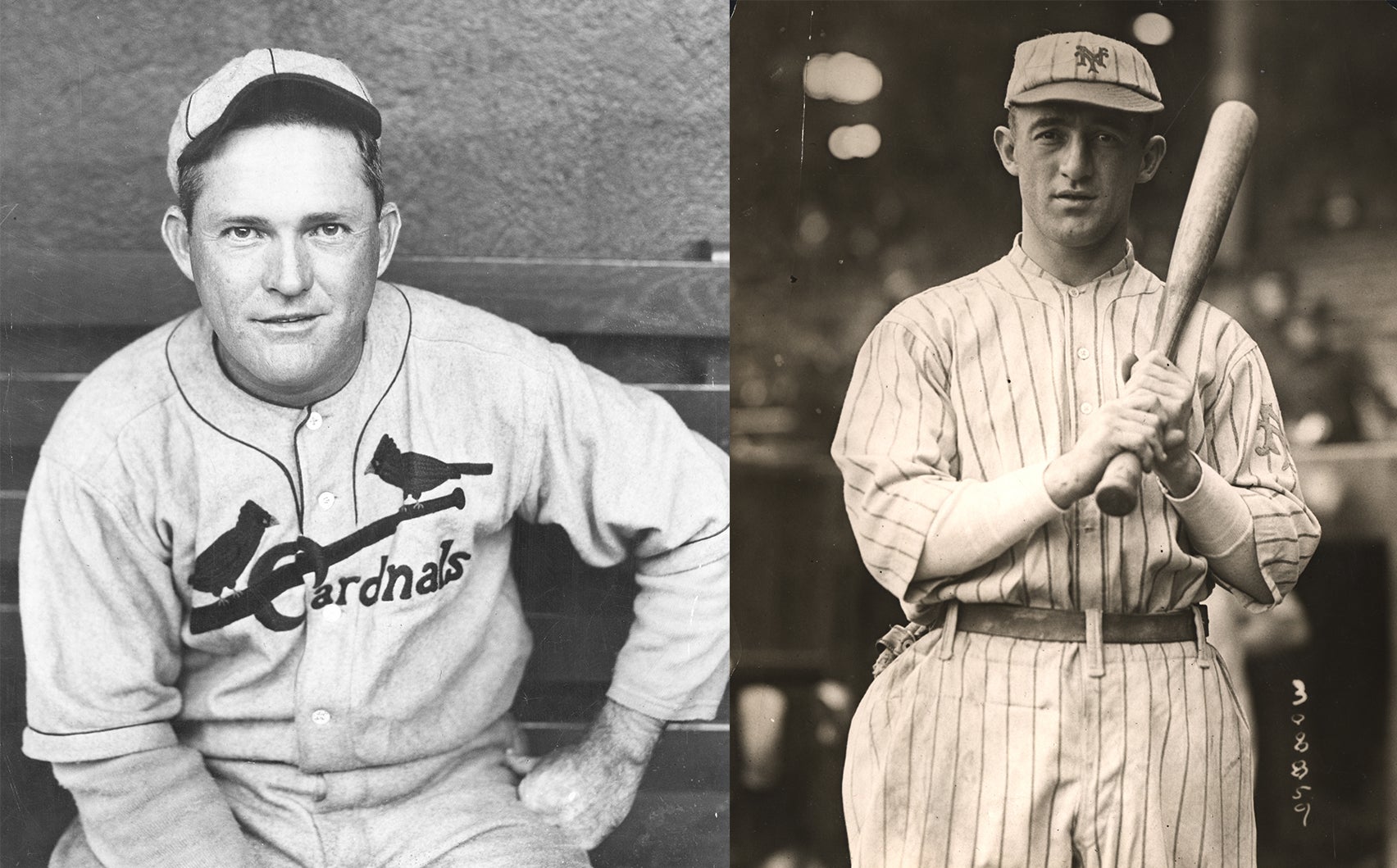

Including Hornsby, eight of the 16 AL/NL teams were now being led by player-managers, a list that also included future Hall of Famers Cobb (Detroit Tigers), George Sisler (St. Louis Browns), Bucky Harris (Washington Nationals), Eddie Collins (Chicago White Sox), Dave Bancroft (Boston Braves), Tris Speaker (Cleveland Indians) and Rabbit Maranville (Chicago Cubs).

Ultimately, Hornsby led the 1925 Cardinals to a respectable fourth-place finish with a record of 77-76. According to his players, one of Hornsby’s hard-and-fast rules was if a batter took a third strike with a runner on second or third base, it cost him $50. “If it’s close enough to call,” Hornsby said, “it’s sure as hell close enough to hit.”

After being voted 1925’s NL MVP in December – the Hall of Fame’s collection contains the bronze medallion he was given for winning the award – newspaper headlines the next day touted: “Rogers Hornsby is ruler without a rival today” and “Card chieftain stamped as king.”

Known as tough and outspoken, Hornsby was a mystery to those he played with.

“Nobody knows him,” said Ferdie Schupp, former Cards teammate. “He never talks to anybody. He just goes out and plays second base and when the game is over, he comes into the clubhouse, takes off his uniform, takes a shower and gets dressed without saying a word. Then he leaves the clubhouse and nobody knows where he goes.”

Hornsby ended his 23-season playing career in 1937, having spent time with the Cardinals, New York Giants, Boston Braves, Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Browns. His .358 lifetime batting average is second to only Cobb’s .366 in AL/NL history. And besides his two MVPs, with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1925 and the Chicago Cubs in 1929, he captured two Triple Crowns (1922 and 1925) and won seven Senior Circuit batting crowns (including a league record six consecutively from 1920-25).

In 1926, his first full season as player-manager, he led the Cardinals to their first pennant since they joined the NL in 1892 and to victory in the World Series.

Hornsby died on Jan. 5, 1963, at the age of 66, but not before being elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1942.

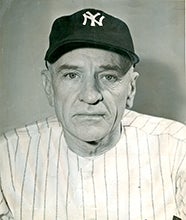

When Casey Stengel, for whom Hornsby would serve as a coach with the 1962 Mets, managed Boston’s NL franchise in the late 1930s and early ‘40s, his batters would sometimes complain about the strong gusts that blew in off the Charles River onto Braves Field.

The skipper would then reply sarcastically, “Yeah, I know, it’s terrible. Hornsby played here one year and hit only .387 against the wind.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum