- Home

- Our Stories

- Charley Pride was a star on the field and at the mic

Charley Pride was a star on the field and at the mic

Charley Pride never made it to the Hall of Fame as a ballplayer.

But as one of the most successful singers in country music history, Pride inspired millions of fans – and found his way to Cooperstown.

Pride, who passed away on Dec. 12, 2020, at the age of 86, performed at the 2006 National Baseball Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Pride, who considered himself a ballplayer until a series of injuries forced him into a different life path, used his baritone voice to forge a groundbreaking singing career, which included his 2000 induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Born March 18, 1938 in Sledge, Miss., a love of baseball developed within Pride from as far back as he could remember.

“We’d be out in the cotton fields and I can remember I sneaked back and I heard The Shot Heard Round the World by Bobby Thomson in 1951,” Pride told the Hall of Fame in 2006. “I kept wanting to go up to the house and get some water. Daddy said, ‘No one can be drinking that much water.’ So he followed me up there and was turning the radio on listening to the game.”

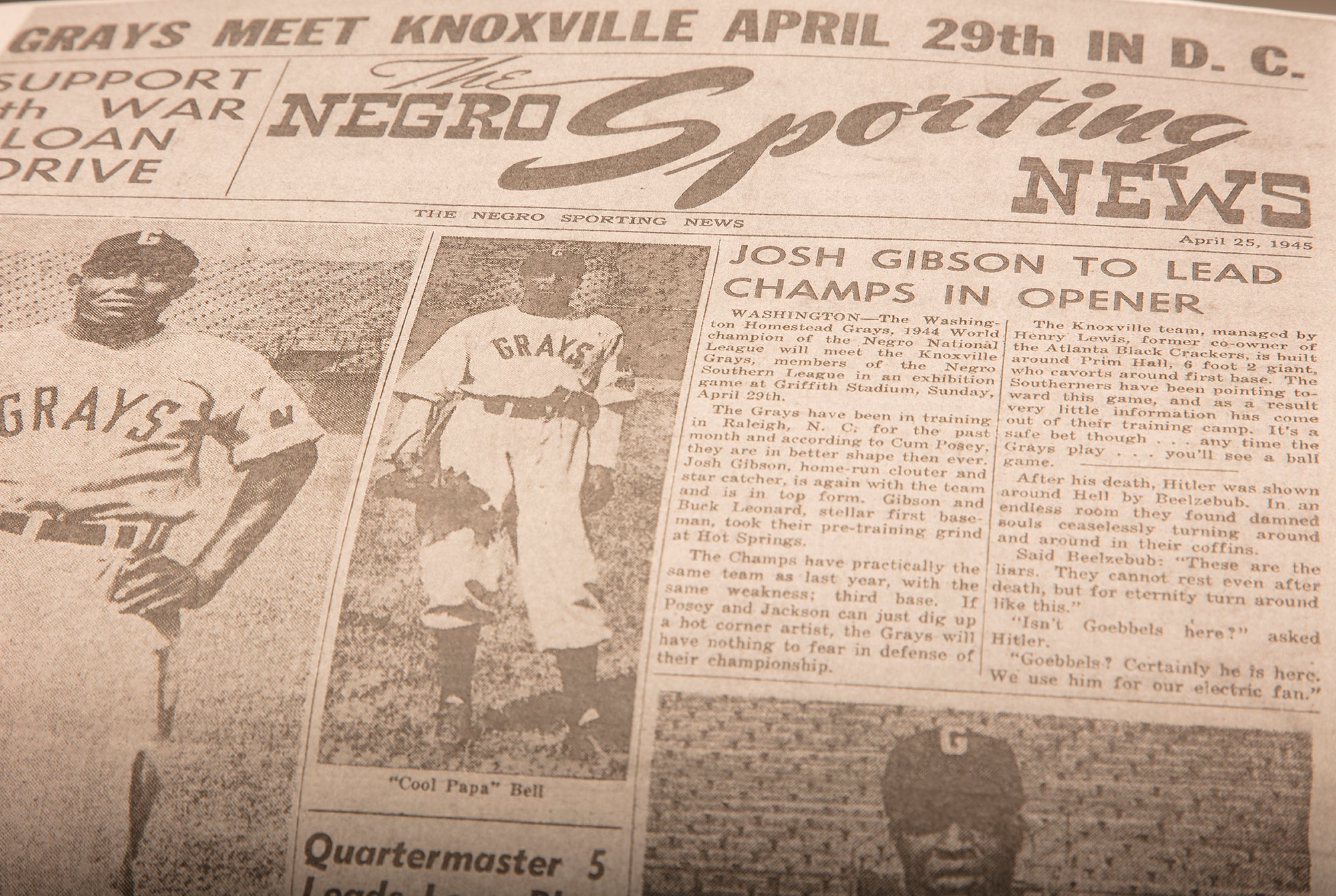

This love of the National Pastime manifested itself into a ball playing career, with Pride leaving home at 16 to play in the Negro American League with the Memphis Red Sox. A pitcher and outfielder, Pride fancied himself as the second coming of another legendary player.

“I love the game. My thing in life was to go to the major leagues and break all the records by the time I was 35 or 36 and then go sing. But it didn’t work out that way,” Pride said. “I was aiming (to be) Babe Ruth. He was a pitcher and an outfielder and I was a pitcher and outfielder.”

According to Pride, while playing ball with Memphis he was being paid $100 a month and $2 a day meal money. And was once traded for a bus…sort of.

“I got away from the Red Sox and was then signed by the manager with a team called the Louisville Clippers,” he said. “Two of us were sold to the Birmingham Black Barons so the Clippers could pay for a bus to travel in.”

It was in 1956 – after rejoining Memphis – that Pride thought he had his one big chance of playing in the big leagues.

“The chief scout of the St. Louis Cardinals was there. I threw a curveball and cracked my elbow,” Pride said. “I was really humming that night, having struck out the side the inning before, and I believe had I not cracked my elbow that it would have been Bob Gibson and Charley Pride with the Cardinals. I would have been picked up that night. “My fastball was in the 90s, and I had all three pitches – the hummer, the hook and the change. And I could get you out with all three. Plus I played outfielder for four days and then I’d take my turn pitching.” After a successful season with Memphis, he was asked to barnstorm in the offseason on a team that would play against the Willie Mays All-Stars, which included such stars as Hank Aaron, Monte Irvin and Elston Howard. “I held them for four innings, shutout ball, in a game in Victoria, Texas. “I’ve got that clipping. I love it and I pass it around all the time.” But after a number of baseball stops, music finally took hold. By the mid-1960s, he was a success – often called the first successful Black country and western singer. But he always envisioned himself getting hits with a bat instead of a vinyl record. Pride did get his chance in the big leagues, however, when the Texas Rangers played him at designated hitter in a Spring Training game on March 18, 1974. Pride went 1-for-2 with a single off future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer. “I never felt at any time that I’d be where I am today, just be doing something I love to do, and that was sing. I was preparing myself to be in the Baseball Hall of Fame, but instead I’m in the Country Music Hall of Fame,” Pride said. “I’m glad to be there, and it’s wonderful, but my idea was always to do it in Cooperstown.” After Pride attended the 2005 Induction Weekend, he was asked to perform the national anthems in 2006. And while he says he has no regrets in the way his life turned out, there are those occasions where he wonders what might have happened. “The way I look at it right now I’ve got the best of both worlds because I can still go out and work out with the guys and still feel that little ting of happiness that I used to get when I went out on the field, hitting and throwing and playing,” Pride said. “All in all I’m a very blessed and a very lucky person. I would have loved to have been one of those names called (on the Induction stage), but I do get a thrill just being around those guys. Baseball is something I always loved.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum