- Home

- Our Stories

- Doby was Second to None

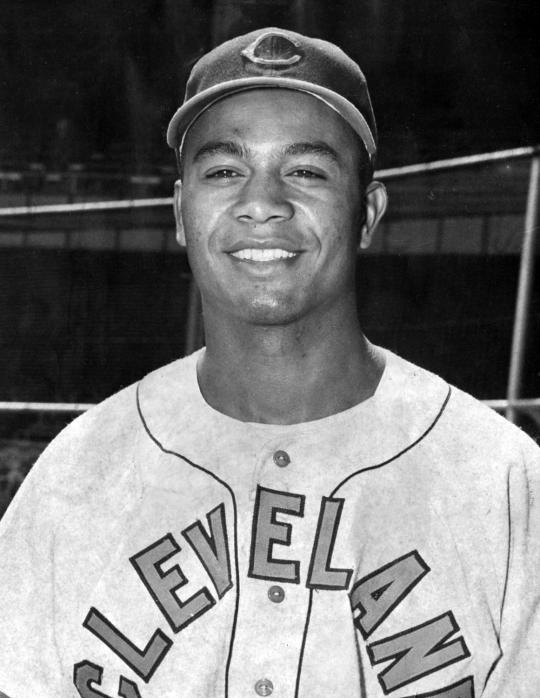

Doby was Second to None

During the fall of 2011, Dodgers and baseball legend Don Newcombe kept throwing fastballs wrapped in Black history over the phone from his home in Los Angeles to my ears in Atlanta. I listened even more intently when our discussion turned to heroes.

Black ones, of course.

He mentioned Jesse Owens and Joe Louis, Black athletes who survived and prospered during the middle of the 20th century while battling opponents for the ages along with a heavy dose of racism.

As the nation watched with much of the world, Owens and Louis began to share their spotlight with Newcombe and other Major League Baseball players after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier on April 15, 1947, with the hometown Dodgers in Brooklyn.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

“I think we had more of a need for Black heroes at that point in history, because of what was going on around the country,” Newcombe said, referring to everything from the ongoing segregation in the Jim Crow South to the racial ugliness suffered by Black players during the early years of integrated Major League Baseball.

“What we did – Jackie, Roy (Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella) and I and Larry Doby,” Newcombe said, pausing before he emphasized with a strong voice, “And don’t forget about Larry Doby.”

Then Newcombe continued hurling those fastballs by adding, “Even though we were athletes, we had a belief (during our AL/NL playing years of the 1940s and the 1950s) that there was more that needed to be done by us to make it a better country to live in.”

I couldn’t shake Newcombe’s phrase …

“And don’t forget about Larry Doby.”

Folks often forget about Larry Doby.

Don’t forget about Larry Doby!

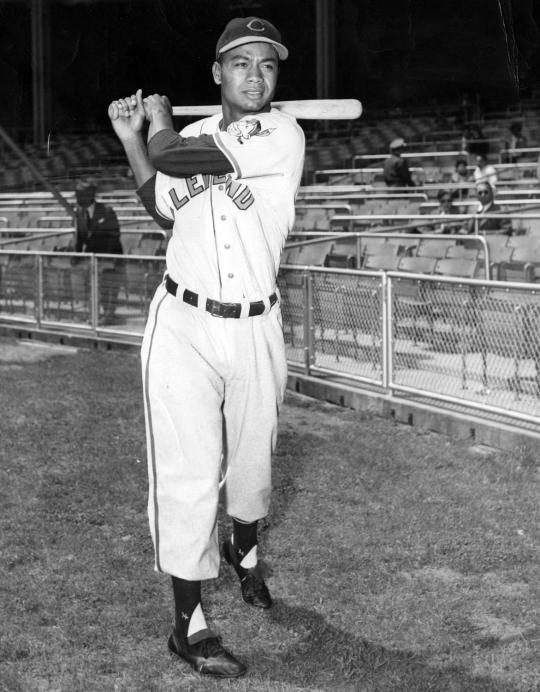

Slightly less than three months after Robinson’s Dodgers debut, Doby walked into the visiting clubhouse at Comiskey Park in Chicago on Saturday, July 5, 1947, to pull on a uniform for the Cleveland Indians. He became the game’s second modern-day Black player overall, but since Robinson’s Dodgers were in the National League, Doby was the first Black player in the American League.

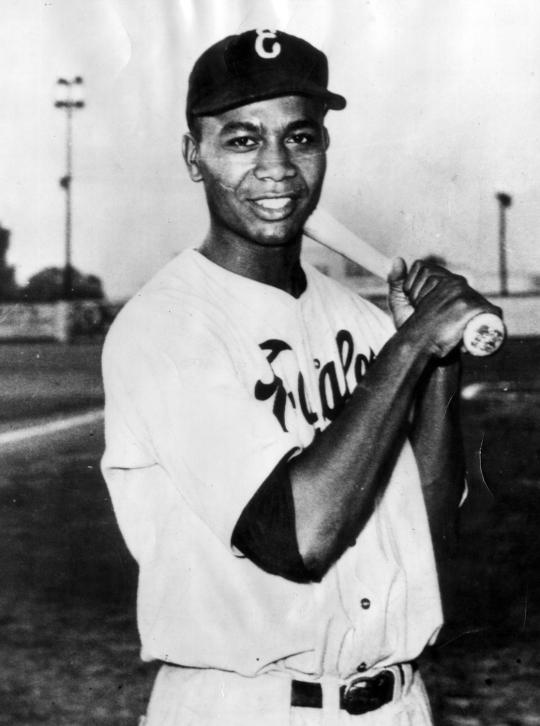

He could play, too. After he spent his pre-AL career – including a prolific stint with the Newark Eagles in the Negro Leagues – as an infielder, he was forced to learn outfield play in a flash with Cleveland. Gold Gloves weren’t awarded for great fielding until 1957, but if they were around during Doby’s prime in center field, he would have captured a slew of them.

Don’t forget about Larry Doby!

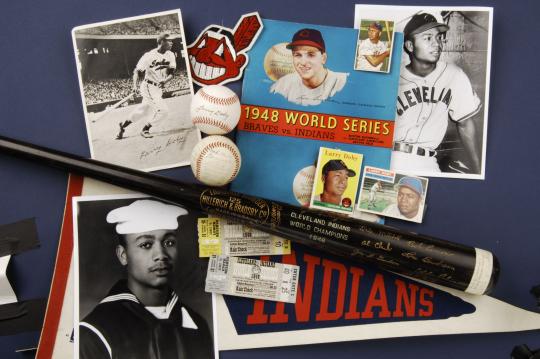

Courtesy of his glove and his bat, Doby made seven trips to the AL/NL All-Star Game. He won AL home run titles in 1952 and 1954, and he led the league in RBI in 1954. On Oct. 9, 1948, he became the first Black player to homer in the World Series, a blast that came as part of Cleveland’s six-game series victory over the Boston Braves. He also did the most to push the Indians into the 1954 World Series (which they lost to the Giants) by finishing second in the AL Most Valuable Player voting.

By the time he retired in 1959 – after 17 seasons in the Negro Leagues and American League – Doby had totaled 273 home runs, drove in 1099 runs and carried a career .288 batting average.

Four decades later, in 1998, Doby was elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee for two reasons: He had his brilliance between the foul lines, and he had his ability to join Robinson in conquering the first wave of racism for Black players by using his brain as well as his brawn.

“My father was humble, modest, and he didn’t talk a lot about the stuff that he did as a player,” Larry Doby Jr. said, describing the man who grew up in Camden, S.C., and later Paterson, N.J., where he spent his high school years meeting Helyn, his wife of 55 years.

Larry Jr., was the only son among five children for the Dobys. He is 64 now, but he hasn’t forgotten how he tried to pry as much history as possible from the mind of Larry Sr. – who died at 79 on June 18, 2003.

“It was very frustrating being a kid and wanting to know about all of this stuff and wanting to hear about it from your dad, but he didn’t want to talk about it,” Larry Jr. said. “As I get older, I begin to wonder why he didn’t want to talk about it, and I don’t know if it was painful. I don’t know if it was that (he thought) it served no purpose in his life at that point, even though I can’t see how it couldn’t have.

“Anyway, he didn’t want to talk about it.”

That doesn’t change the bottom line …

Don’t forget about Larry Doby!

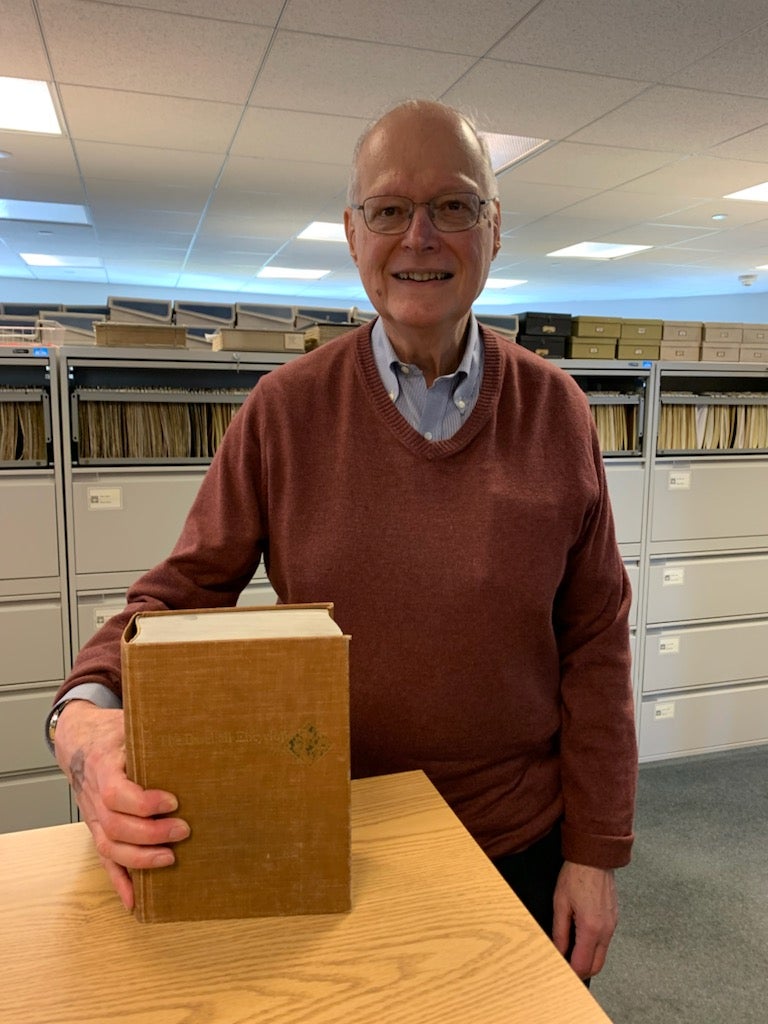

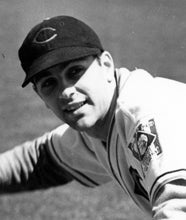

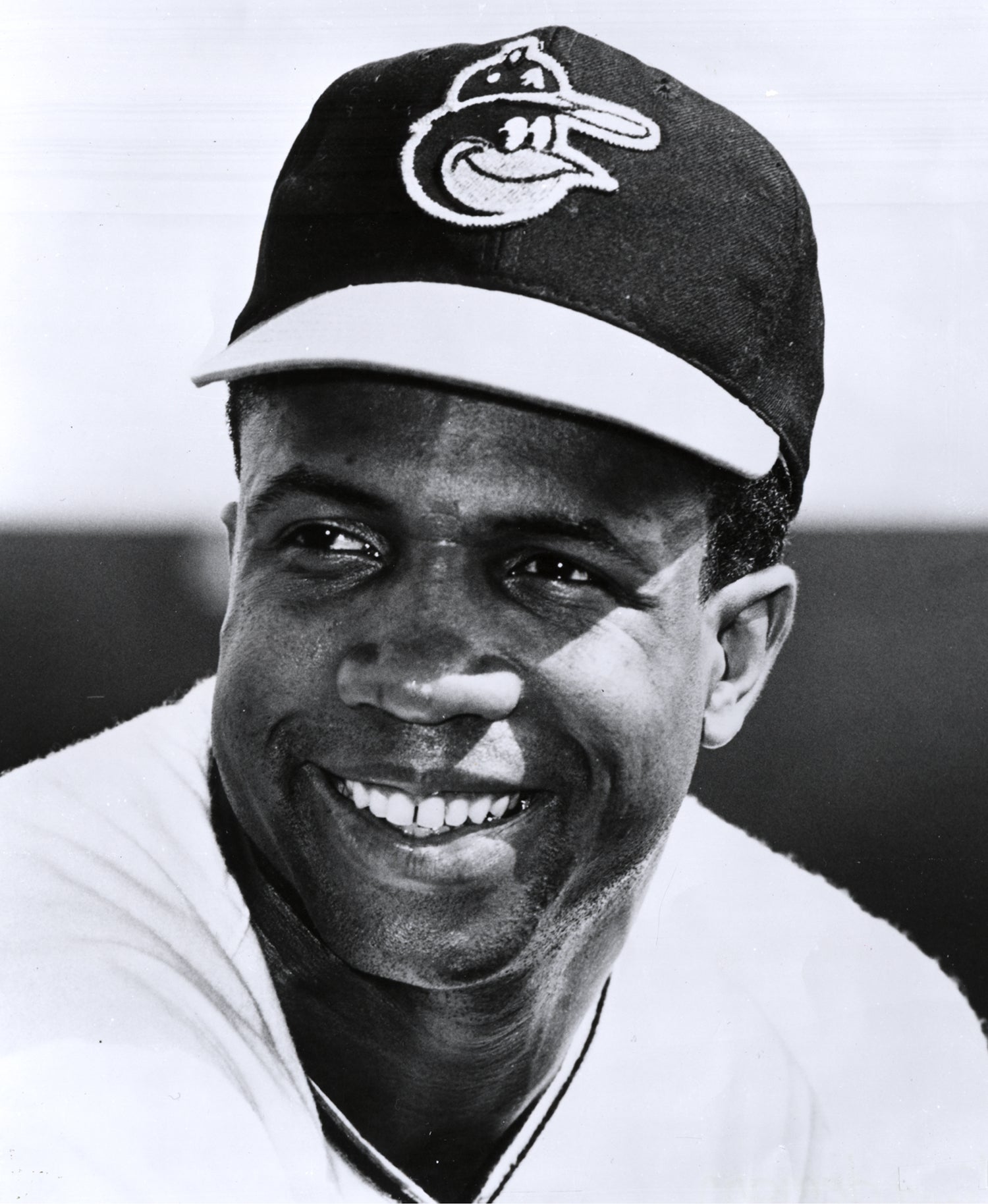

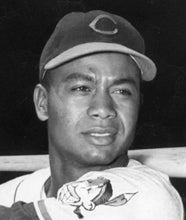

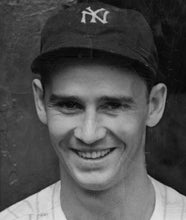

Larry Doby’s historic career included starring with the Negro League’s Newark Eagles, nine All-Star Game selections in the American League and becoming the second Black manager in AL history with the White Sox in 1978. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In Cleveland, where Doby used to say he was never booed, they gave him a street and a statue. The franchise also regularly honors Doby (retired number, franchise Hall of Fame, etc.), but outside of northern Ohio and baseball historians, many folks have forgotten about Larry Doby.

THE MONTCLAIR, N.J., THING

With much help from Doby’s first nine AL seasons of on-the-field glory for the Indians through 1955, he became a Hall of Famer. Even so, the most popular Cooperstown guy in Montclair, N.J., where Doby spent the bulk of his life with his wife and children, was Yogi Berra, the New York Yankees catcher, slugger and master of Yogisms to the delight of the universe.

THE BUZZ ALDRIN THING

Doby wasn’t even the most famous “second” person in Montclair. Buzz Aldrin also lived there, and he took three spacewalks in 1966 as an American astronaut. Then, after Neil Armstrong made “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” on July 20, 1969, by becoming the first person to walk on the moon, Aldrin followed Armstrong as No. 2.

THE OTHER ROBINSON THING

Cleveland made future Baseball Hall of Famer Frank Robinson its player-manager in 1975, which turned this Robinson into the first Black manager in the AL or NL. Three years later, the Bill Veeck who owned the Indians in July 1947 – when he acquired Doby from the Newark Eagles of the Negro Leagues – was the same Bill Veeck who owned the White Sox on June 30, 1978, when he promoted Doby from batting coach for the team to manager for the rest of the season. But Doby’s notoriety as a Black manager was muted since Frank Robinson already had been there, done that.

THE SATURDAY, JULY 5, 1947, THING

One moment, Doby was with the Eagles in Newark, where he finished the first game of a doubleheader in 1947 on the Fourth of July hitting .415 with 14 homers in the Negro Leagues. The next, he was getting word from team ownership that he had been sold for $15,000 to Veeck’s Indians. Soon, Doby joined Indians official Louis Jones for a train ride from Newark to Chicago, where the two Black men traveled to the south side the following day for Cleveland’s game against the White Sox at Comiskey Park. When Doby pinch hit in the seventh inning on Saturday, July 5, it was historic, but it wasn’t Jackie Robinson historic.

Not that it mattered to Doby.

Take it from Larry Jr., who remains in the family’s long-time house in Montclair. He has spent decades working on the road crew for famed singer Billy Joel. So, Larry Jr. had that job, but when Larry Doby Sr. was alive, Larry Jr. also had another one: Trying to get his father to share his baseball past. Instead, the son got only bits and pieces from the father who mostly shrugged over his status.

Many of those conversations involved Doby’s early years in the American League. There was his first day with the Indians, for instance. After player-manager Lou Boudreau introduced Doby to everybody in the visiting clubhouse that afternoon at Comiskey Park, some players turned their backs toward Doby as he tried to greet them, and others ignored his outstretched hand. Future Baseball Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Gordon was the only one who would play catch with Doby before his first game.

Doby was a pinch hitter that day against the White Sox, and he did the same the next afternoon during the first game of a doubleheader. Then came the second game, when Boudreau wanted Doby to play first, but since Doby mostly was a second baseman, he lacked a mitt for the position.

None of his teammates would loan him the correct glove.

Gordon borrowed one for Doby from a White Sox player.

You get the picture: Just like Robinson, Doby survived the bigotry – of teammates, of opposing players, of fans on the road, of the media (who called everything from “surly” to “a malcontent” in for his quiet ways), of segregated hotels, restaurants, schools and neighborhoods – to become elite on the field among his peers. Even then, he couldn’t escape the racial issues, which was exemplified in 1954 when he shined the most as a player.

Doby led the American League that year with 32 home runs and 126 RBI, and he remained potent enough in center field to use his fielding and hitting to help the Indians end the Yankees’ string of five straight pennants. In the end, Cleveland managed a then-AL-record 111 victories, but it wasn’t enough for the writers voting for the 1954 AL Most Valuable Player. They gave the award to Berra, the Yankees’ white catcher, even though Berra ended with fewer home runs (22) and RBI (125) than Doby, and his Yankees finished eight games behind in the standings.

Doby and Robinson discussed such slights – and various triumphs – during phone calls through the years.

“My father had the utmost respect for him, and he always referred to him as Mr. Robinson,” Larry Jr., said of Larry Sr., who was a pallbearer at Robinson’s funeral in October 1972. “They were close. They did talk about who the good guys were, the bench jockeys, you know, which cities were rough. And they also barnstormed together. That was pretty cool, and it was a ‘who’s who’ of Black players. I’ve seen a picture from those days, and it’s Campanella. It’s Newcombe. It’s Doby. It’s Hank Thompson. It’s Monte Irvin. It’s Sam Jethroe.

“My father knew that, in 1946, when Mr. Robinson signed with the Montreal Royals (in the minor leagues), he said, ‘Maybe some of us will get a chance.’ He knew somebody had to be No. 1, and somebody had to be No. 2, and my father was perfectly content with being No. 2.”

Doby was more like No. 1B.

Terence Moore is a freelance writer from Smyrna, Ga.