- Home

- Our Stories

- Cooperstown Connections

Cooperstown Connections

Small town has big baseball names among its citizenry

With its approximately 2,000 year-round residents, a figure as true today as it was 100 years ago, Cooperstown, N.Y., has been known over the decades as the home of baseball. And though its population is small, it has counted among its denizens some big names in the game’s history.

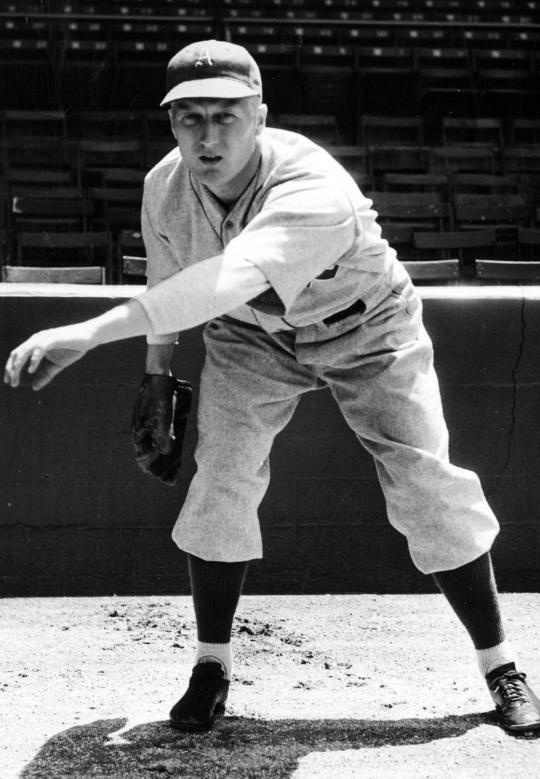

Some 120 years ago, future Hall of Fame pitcher Jack Chesbro, elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1946, could be found playing semipro ball with the Cooperstown Athletics. The right-hander, known as “one of the wettest of the spitball brigade,” spent 11 seasons in the big leagues before retiring after the 1909 campaign. His 198-132 career record, which includes winning at least 20 games in a season five times, is highlighted by his modern single-season record 41 victories in 1904 for the New York Highlanders.

The native of North Adams, Mass, nicknamed “Happy Jack” for his sunny disposition on the field, found himself without a hurling job early in his minor league career after spending part of the 1896 season with Roanoke of the Virginia League. But soon enough, he was playing with a Cooperstown team made up mainly of collegiate players.

“Jack Chesbro developed his famous spitball and change of pace when pitching for Cooperstown in 1896, after he had contracted a sore arm in the Virginia League early that season,” claimed George “Deke” White, a Cooperstown teammate of Chesbro’s in 1896 as well as a major league pitcher with the Phillies in 1895. “We needed another pitcher and, being a friend of Jack’s, I advised the Cooperstown management to sign him. He reported and the rest and pitching he got there healed his arm.

Hall of Fame pitcher Jack Chesbro photographed in 1905 as a member of the New York Highlanders. According to his former teammates, Chesbro developed his famous spitball as a member of the semipro Cooperstown Athletics in 1896. BL-1905-1453-61 (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“Chesbro never used his spitball while at Cooperstown but that’s where he perfected it. Only three of us – myself, Chesbro and Lew Rueing, our catcher – knew Jack could throw the (spit)ball and we kept it a secret until Chesbro went up to the majors.”

An Overlooked Talent

While Chesbro was celebrated for his ballfield exploits after leaving Cooperstown, another Leatherstocking region player, Bud Fowler, gained only a limited level of fame due to the color of his skin.

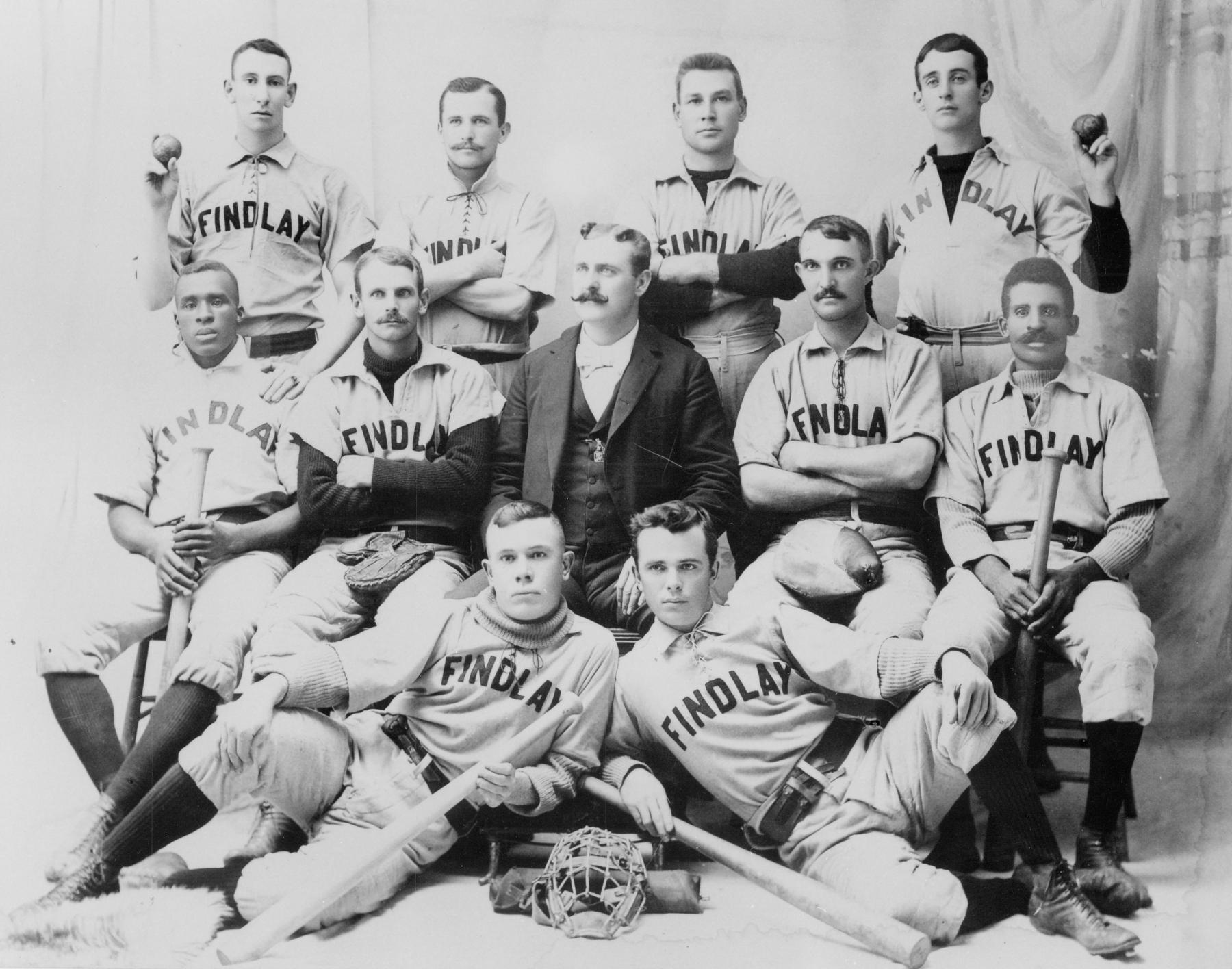

The African-American Fowler was a baseball pioneer in the late 19th century who, though he never played in the major leagues, would become a trailblazing player in the minors nonetheless. Despite constant discrimination, he played at a high level for both black and integrated teams. In 1878, he became the first African-American known to have played for a white professional team, the Lynn (Mass.) Live Oaks of the International Association.

The Cincinnati Enquirer, on Feb. 1916, printed, “Fowler was about three shades darker than the raven’s wing, but was such a clever ballplayer that he found no difficulty in hooking up with clubs playing in organized ball.”

Fowler grew up in Cooperstown under the name of John W. Jackson, and his family moved there when he was only a child. Known mainly as a pitcher, catcher and second baseman, he played professional baseball for almost two decades. He was also a respected promoter of black teams and leagues.

“My skin is against me,” said Fowler in 1895. “If I had not been quite so black, I might have caught on as a Spaniard or something of that kind. The race prejudice is so strong that my black skin barred me.”

Fowler was born March 16, 1858, in Fort Plain, N.Y., and passed away on Feb. 26, 1913, in Frankfort, N.Y. In April 2013, 100 years after his death, Cooperstown dedicated a street to Fowler, named Fowler Way, that leads to historic Doubleday Field.

“A 19th century son of a black barber struggling to play baseball is not quite someone, let’s say, the village perceives as one of their own,” said Cooperstown mayor Jeff Katz at the time of the street dedication. “And yet he is one of our own. He is a fellow resident, a fellow citizen of this village, who did an amazing thing.”

Members of the Cooperstown Central High School team along with town citizens including Mayor Jeff Katz dedicate Fowler Way on April 20, 2013 next to historic Doubleday Field. Fowler, a trailblazing 19th century African-American ballplayer, grew up in Cooperstown under the name John W. Jackson. (Milo Stewart, Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame)

“I just liked the town”

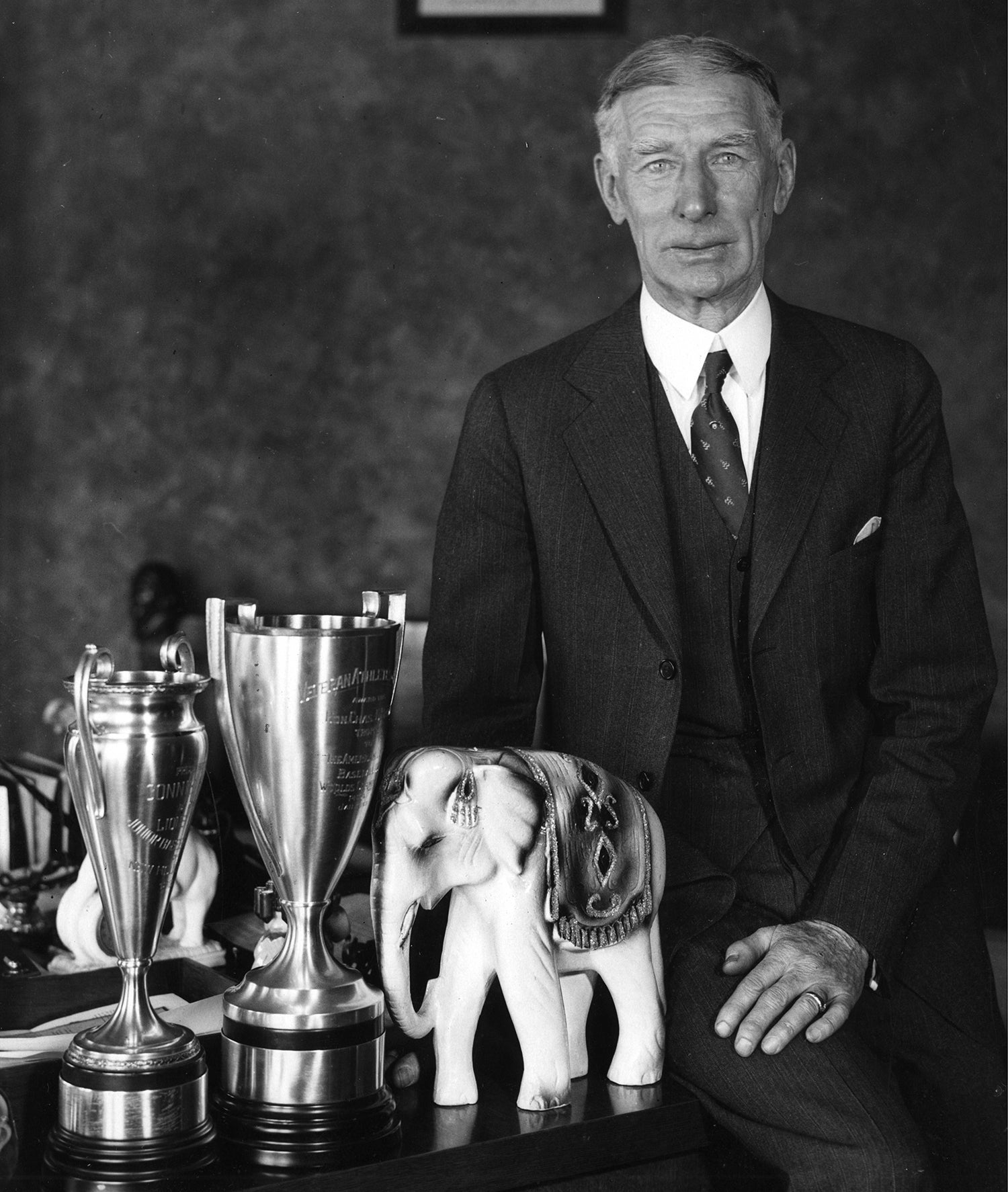

Another citizen of the village, though later in life than when Bud Fowler called Cooperstown home, was former big league pitcher Vernon “Whitey” Wilshere. Familiar with central New York, having been raised in nearby Skaneateles, he was signed off the Indiana University campus, skipped the minors and spent his first three professional seasons, from 1934 to ’36, with Hall of Fame manager Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. A southpaw pitcher, he compiled a career record of 10-12 in 41 games, including a career-best 9-9 mark in 1935.

After an arm injury in 1935 effectively ended baseball career, Wilshere returned to Indiana and eventually earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees. He served five years in the Navy during World War II before moving with his family to Cooperstown in 1953 to work as a salesman for Cayuga Rock Salt. By the mid-1960s, however, Wilshere was employed by Cooperstown Central School as a driver’s education instructor, where he stayed until his retirement in 1980. Along the way, he also spent time as the school’s baseball coach.

“I didn’t really come here because of baseball,” said Wilshere in 1984. “I just liked the town, and the company I was working for at the time wanted me to live in the northeast. I thought it was a good place to bring up children.”

Wilshere passed away at the age of 72 on May 23, 1985. When he was buried in Lakewood Cemetery, he became the first, and thus far only, big leaguer whose final resting place is in Cooperstown.

Clearing home plate for others

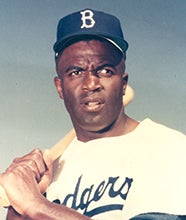

Much like Fowler, African-American umpire Emmett Ashford endured taunts and outright hostility as he embarked on a profession unaccustomed to an arbiter with his skin tone. Born in 1914, and after stints as a postal worker and service in the Navy during World War II, he became the first black umpire in the minor leagues in 1951 in the Southwest International League. Working up the ladder, through a 12-year stint with the Pacific Coast League, Ashford finally brought his distinctive style of animated and loud calls to the big leagues, working in the American League from 1966 to 1970 to become the first black umpire in the majors.

"I have intimate knowledge of the challenges he faced," Rachel Robinson, widow of Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson once wrote. "At that time in America, the need for social change was intense and still to come. Mr. Ashford carried out the role with great skill, determination and courage, thereby, creating opportunities for others to follow him."

According to Ashford, who also worked the 1967 All-Star Game and the 1970 World Series, “My five-year tenure in the majors was one of satisfaction and gratification at having conquered the biggest challenge in my life, and in some measure, opening the door for black umpires. I feel proud having been an umpire in the big leagues, not because I was the first black man, but because major league umpires are a very select group of men.

“But the greatest satisfaction I’ve gotten is the feeling of accomplishment in doing what I set out to do in the first place when they said it couldn’t be done. I only wish it had happened sooner, but there’s no point crying about it. It took a long time, sure, but it also took the covered wagons a long time to get across the plains.”

Ashford died on March 1, 1980, at the age of 65. His widow, it has been reported, requested his ashes be buried in Cooperstown. Today his remains can be found, like Wilshere’s, at Lakewood Cemetery.

Ashford famously umpired in Cooperstown at the 1968 Hall of Fame Game, a big league exhibition held at Doubleday Field that has since been replaced by the Hall of Fame Classic. In reporting the outcome of the July 22 contest the next day, the local Oneonta Star newspaper spent its first few paragraphs extolling the joy that Ashford brought to his role working behind the plate.

“If a popularity poll could have been taken after Monday’s Hall of Fame game among the 10,000 fans at Doubleday Field,” the paper wrote, “the Detroit Tigers and Pittsburgh Pirates would have finished a poor second to umpire Emmett Ashford

“Because while the Tigers were busy burying the Pirates, 10-1, Ashford was busy stealing the show.

“‘Popular’ is a strange adjective to be linked with an ‘umpire,’ but even that adjective falls short of describing Ashford, who turns a called strike into a work of art.

“And yesterday Emmett was at his best. When the Tigers’ Don Wert sliced a three-run home run in the first, there were cheers. But when Ashford dusted off home plate in his own free-swinging, flailing fashion, there was thunder.

“And after the game, the inimitable American League umpire was virtually engulfed by a descending wave of kids trying to get a closer look at their hero.”

A major league catch

Most recently, in November 2015, the Oakland A’s announced that 2008 Cooperstown High School graduate Phil Pohl had been hired as the major league team’s new bullpen catcher. Pohl was the team’s 28th-round draft pick in 2012 and spent nearly four seasons as a catcher in the farm system before he was traded to the Rockies in June 2015.

According to reports, A’s manager Bob Melvin liked the fact that Pohl is both athletic and the age of many of the A’s players, adding Pohl “truly is a staff member.”

“It really hasn't sunk in yet (not being an active player any more) because I'm still doing work in the cage and I'm still doing work behind the plate,” said Pohl during a recent Spring Training interview with the Hall of Fame. “And when the A's came to me in October and talked to me about the job, I thought, ‘I'm still healthy, I'm only 25, and I could catch on somewhere as a backup.’

"But the more I thought about it, the more I realized what a tremendous opportunity it is to be on a big league staff at 25. I really was in the right place at the right time. And to have a chance to be on a staff with a guy like (third base coach) Ron Washington, who's been in the game forever, and Bob Melvin, who's done such a great job with Oakland the last few years, is a dream come true.”

Born in Bakersfield, Calif., Pohl and his family would later move to Cooperstown, where he lettered four times in baseball. As a high school junior, he was the New York State Class C Player of the Year after hitting .509 with five homers, 39 RBI and 41 steals. After graduating from high school, he was selected by the Tampa Bay Rays in the 44th round of the amateur draft, but he attended Clemson University instead of going pro.

“I was a young senior coming out of high school,” said Pohl in an earlier interview. “I was 17 years old and I thought at that point in my life it was better for me to go to college right out.

“Looking back, I think I made the right decision.”

Bill Francis is a library associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum