- Home

- Our Stories

- Gehrig, Hunter and Frates each furthered cause of ALS cure

Gehrig, Hunter and Frates each furthered cause of ALS cure

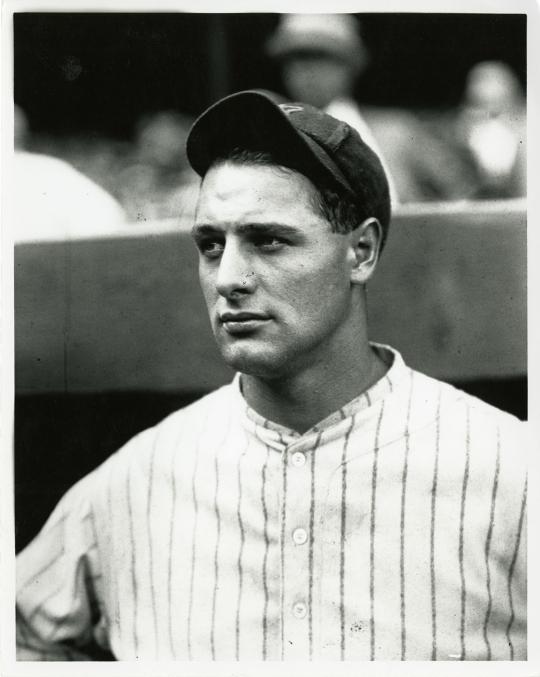

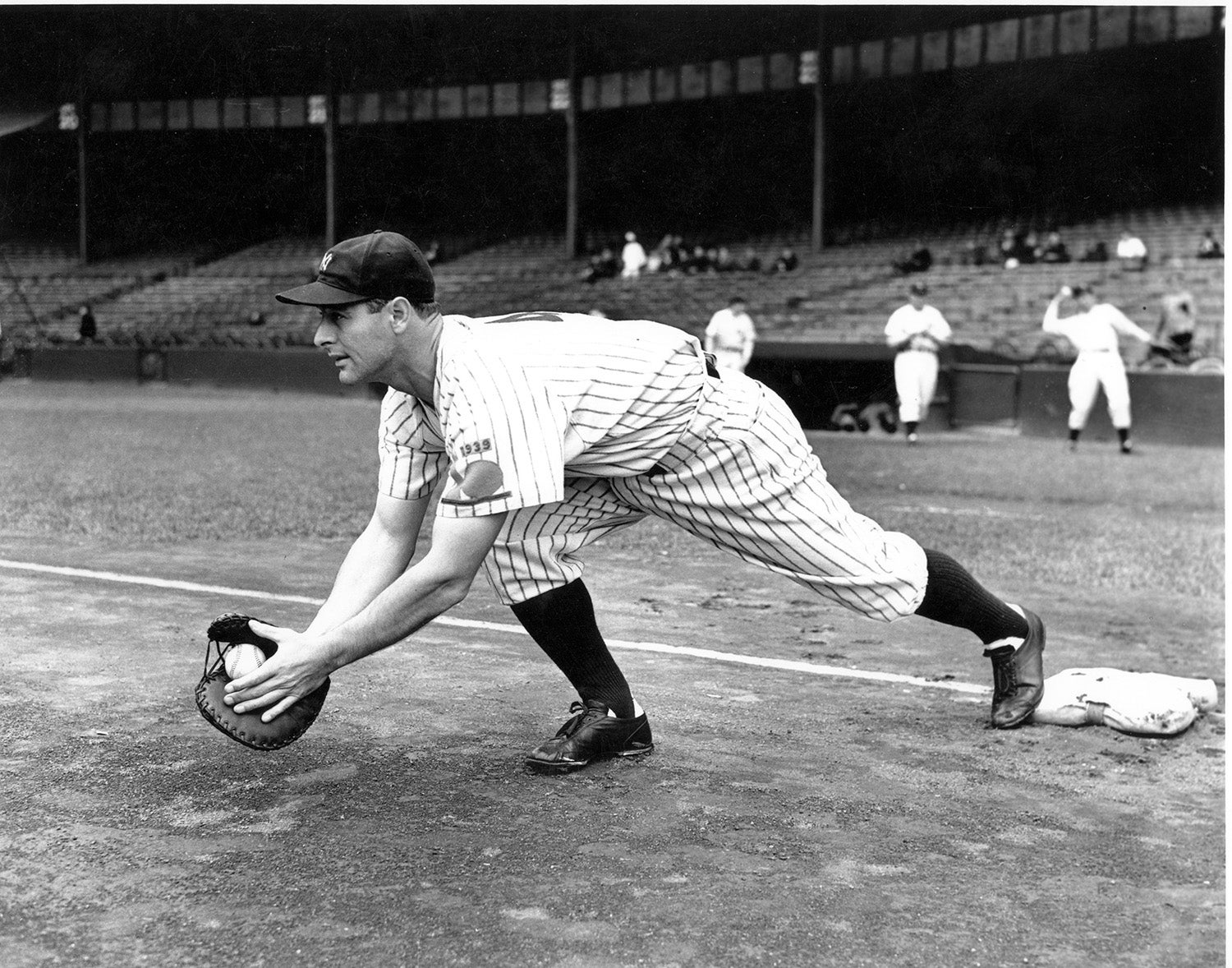

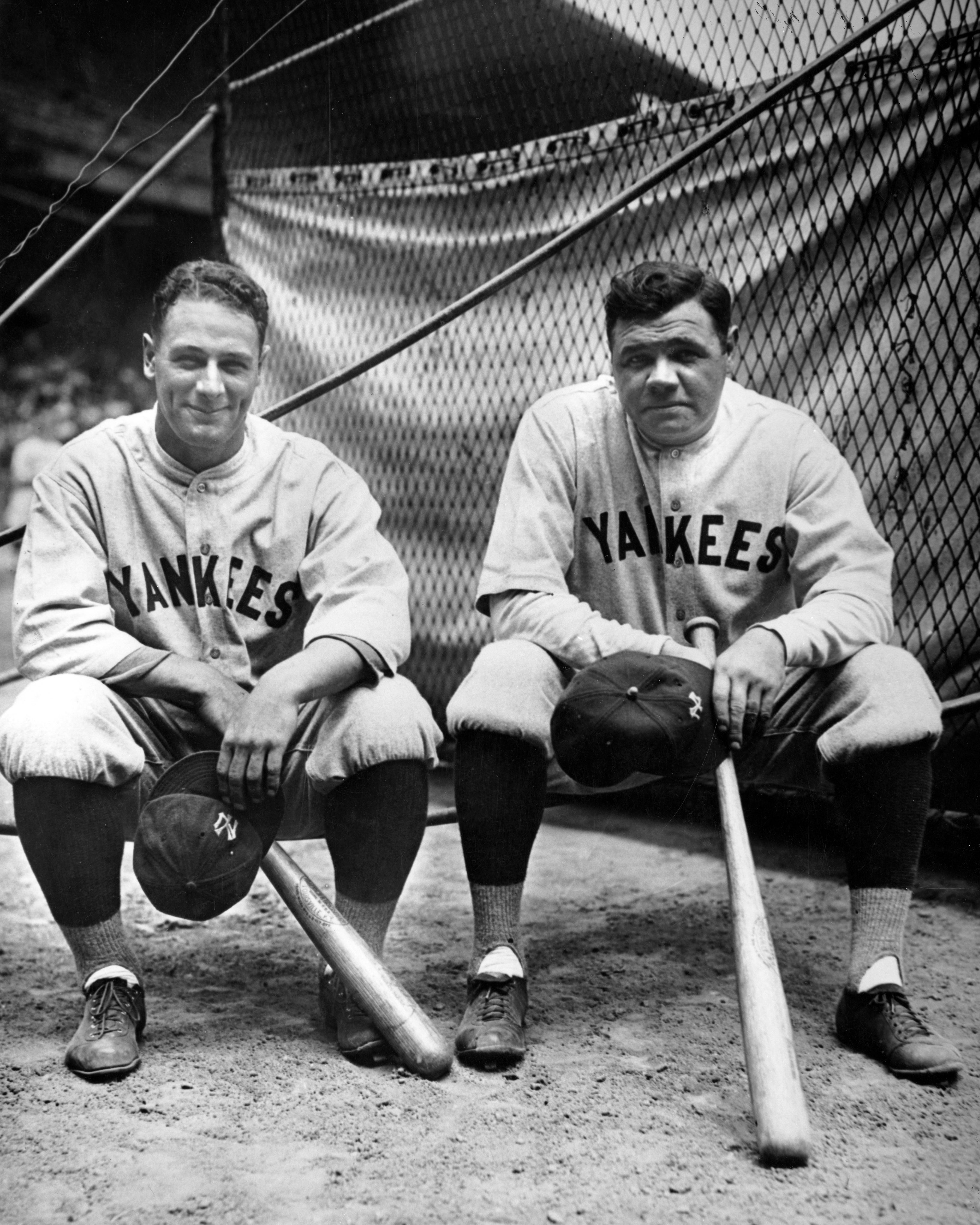

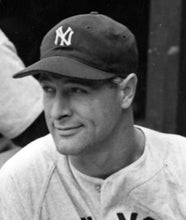

Nearly eight decades ago, Lou Gehrig famously shared with the world a shocking medical diagnosis that would explain the once-strapping physical specimen’s precipitous decline as a ballplayer.

Since then, others in the baseball fraternity, including fellow Hall of Famer Jim “Catfish” Hunter and former Boston College captain Pete Frates, have revealed that they, too, had Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.

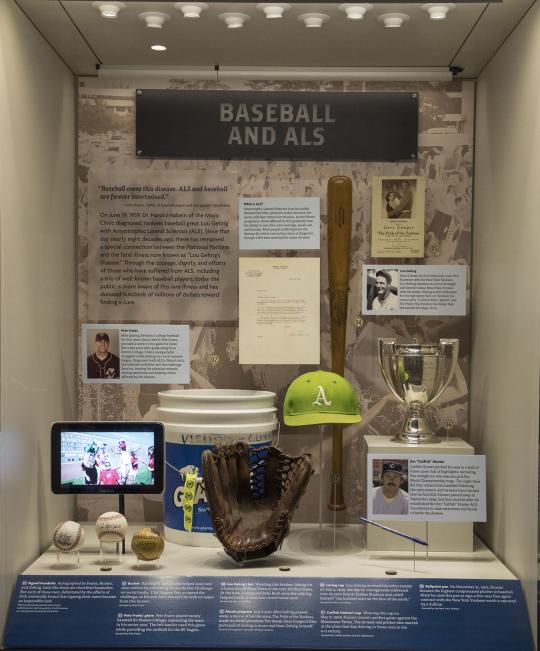

The stories of Gehrig, Hunter and Frates are highlighted at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in “Baseball and ALS,” an exhibit located on the Museum’s second floor at the end of the “Whole New Ballgame” exhibit. Opened in April, it shares the National Pastime’s intertwining relationship with ALS beginning with the Iron Horse’s pronouncement in 1939 and how this specific trio of players brought awareness to the insidious disease in different ways through their courage and dignity.

ALS, better known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, is an incurable condition that disables a person’s motor neurons, the nerve cells that control our muscles. As the illness progresses, those affected by ALS gradually lose the ability to use their arms and legs, speak, eat and breathe. Most people suffering from the disease pass away within two to four years of diagnosis, though a few have survived for many decades.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“Our ‘Whole New Ballgame’ exhibit explores baseball stories that are relevant today by giving them historical context,” said Hall of Fame Senior Curator Tom Shieber. “The success of the Ice Bucket Challenge in raising over $250 million for ALS research while simultaneously raising public awareness of Lou Gehrig’s Disease provided us with an excellent opportunity to create a small but engaging exhibit about the special connection that our National Pastime has long had with the terrible illness.”

In Gehrig’s case, he was coming off a respectable but disappointing for him 1938 campaign. He hit 29 home runs and drove in 114, but batted only .295, the first time he had hit under .300 since 1925. He was determined to return his game to its past glory, but when next spring arrived his reflexes had slowed alarmingly.

When the 1939 regular season began, the 35-year-old Gehrig batted only .143 with one RBI and no extra-base hits through the Yankees’ first eight games. Finally, on May 2, 1939, in Detroit, Gehrig took himself out of the lineup after a then-record 2,130 consecutive games.

“On Sunday, April 30, we got our second straight setback from the Senators in the Stadium,” Gehrig said. “In the ninth, Buddy Myer slapped one down to me, and in other years I would have stuck the ball into my back pocket. But it was a hard play for me and I tossed to (pitcher Johnny) Murphy, who had covered the bag.

“When I returned to the bench, the boys said, ‘Great play, Lou.’ I said to myself, ‘Heavens, has it reached that stage?’”

Eventually, Gehrig decided to put himself in the hands of the experts at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., to determine just why he had lost his baseball abilities so suddenly.

After being examined by Mayo Clinic physicians from June 13 to 19, Gehrig returned to New York, where he presented the famed medical institution’s report, received on his 36th birthday, to Yankees manager Joe McCarthy and team president Ed Barrow at Yankee Stadium on June 21. After a conference in McCarthy’s office, Barrow read the report from Dr. Harold Hobein to an anxious media throng.

“After a careful and complete examination it was found that he is suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” the statement read in part. “This type of illness involves the motor pathways and cells of the central nervous system and in lay terms is known as a form of chronic poliomyelitis – infantile paralysis.

“The nature of this trouble makes it such that Mr. Gehrig will be unable to continue his active participation as a baseball player inasmuch as it is advisable that he conserve his muscular energy. He could, however, continue in some executive activity.”

Despite the diagnosis, Gehrig joked about the many physical examinations he underwent at the Mayo Clinic. “They even made an x-ray picture of my head,” he said, before adding with a grin, “but they didn’t find anything there.”

It was on July 4, 1939, Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day, when the longtime Yankee first baseman uttered the famous words at a home plate ceremony at Yankee Stadium: “Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about a bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

The next day’s New York Times wrote “the vast gathering, sitting in absolute silence for a longer period than perhaps any baseball crowd in history, heard Gehrig himself deliver as amazing a valedictory as ever came from a ball player.”

The Independence Day event, held between games of a doubleheader against the visiting Washington Senators, saw 61,808 fans pack the bunting-draped ballpark.

On Dec. 7, 1939, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America voted unanimously to suspend the waiting period and placed Gehrig in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Less than two years later, Gehrig died at the age of 37 on June 2, 1941.

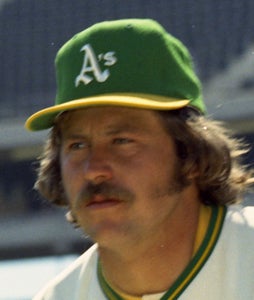

Hunter, an eight-time All-Star pitcher with five straight 20-win seasons and a contributor to five World Series titles, retired in 1979 at the age of 33 after a 15-year career with the A’s and Yankees. He was diagnosed at a Baltimore hospital with ALS in September 1998 after experiencing problems with his motor skills.

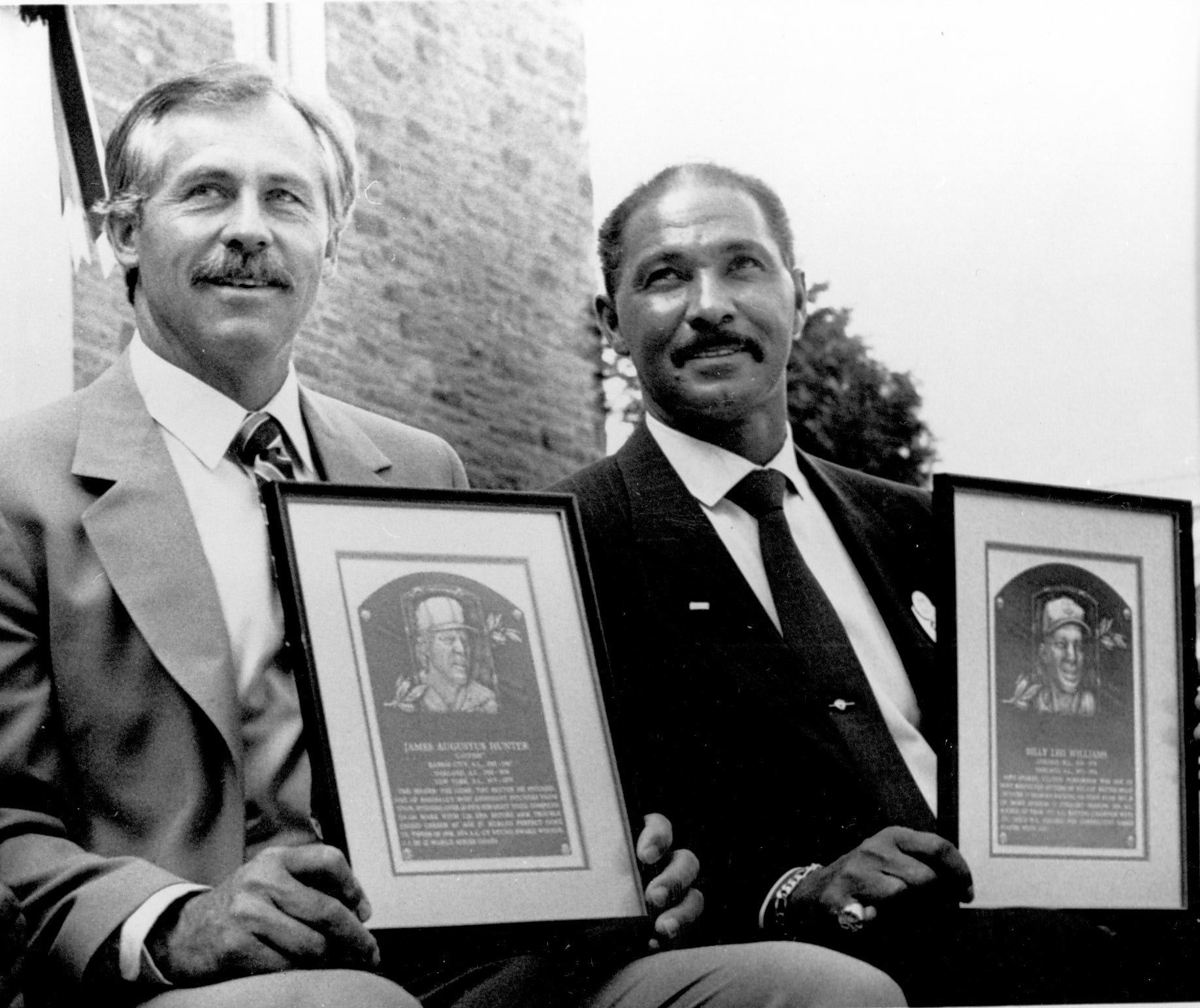

The “Baseball and ALS,” exhibit is located on the Museum’s second floor at the end of the “Whole New Ballgame” exhibit. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“Just my hands and arms don’t work. That’s the only thing,” said Hunter, making his final public appearance while attending a Yankees Spring Training game in Tampa on March 4, 1999. “I can’t do the routine things like button a shirt anymore.

“Sometimes you want to cry. Other times you’re still crying but you’re thankful you’re living. But the main thing is maybe there will be a cure for it one of these years and maybe I can last that long.”

Hunter passed away on Sept. 9, 1999, just four months after he established the Jim “Catfish” Hunter ALS Foundation to raise awareness and funds to battle the disease.

The sport’s most recent connection with ALS belongs to Frates, who championed the social media phenomenon called the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. A college baseball player and team captain at Boston College, he was diagnosed with ALS in 2012 after struggling while playing the game in a summer league a few years after graduation.

In the summer of 2014, Frates proved an inspiration for the renewed battled against ALS when he popularized the Ice Bucket Challenge and helped raise over $250 million by promoting it on social media.

“When he was diagnosed the doctors told us, ‘Get his affairs in order, make him comfortable, to live his 2-5 years of life. That was the mindset of the medical community,” said Pete Frates’ father, John Frates, at an ALS Awareness Weekend event at the Hall of Fame in October 2017. “It was ‘Keep this quiet, you are going to lose all of your dignity, keep this under wraps.’ Well if it’s not exposed to the light, how do you raise awareness, how do you start this fundamental process of raising the necessary funds?

“After Pete brought the disease into the modern world and drew awareness to it – with thousands of Ice Bucket Challenges and millions of dollars raised – we’re on the precipice of effective treatment and a cure. There’s no doubt that this new awareness campaign of social media is so powerful.”

Included among the artifacts in the “Baseball and ALS” exhibit are the June 1939 letter Gehrig received from the Mayo Clinic stating that he was suffering from ALS; the bat used by Gehrig to homer off Dizzy Dean in the 1937 All-Star Game; a silver trophy Gehrig received on July 4, 1939; Hunter’s cap from his 1968 perfect game; a ballpoint pen Hunter used to sign a free-agent deal with the Yankees on Dec. 31, 1974; Frates’ glove used while playing outfield for Boston College; and the bucket from which Frates’ wife, Julie, doused him with ice water in 2014 for the first time.

“This disease was named after Lou Gehrig. But I think Lou Gehrig would be very proud of Pete that for the fact that ALS is branded now,” said Pete’s brother, Andrew Frates, while at the Hall of Fame’s 2017 ALS Awareness Weekend event . “It’s not Lou Gehrig’s disease any more, it’s ALS. People are learning what ALS stands for – Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Having it branded ALS, rather than Lou Gehrig’s disease, is huge for the ALS community because now people can start Googling ALS, Googling other symptoms of what that is. I think Lou would be proud of Pete for that.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum