- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Agent for the Babe

#GoingDeep: Agent for the Babe

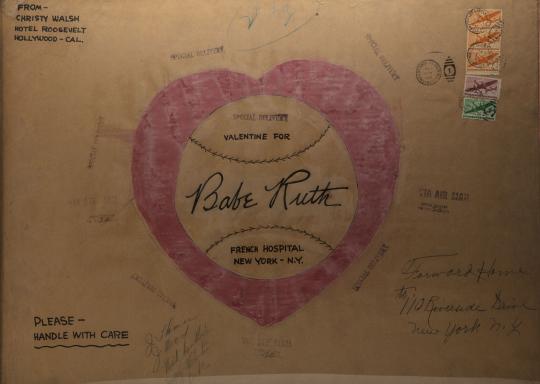

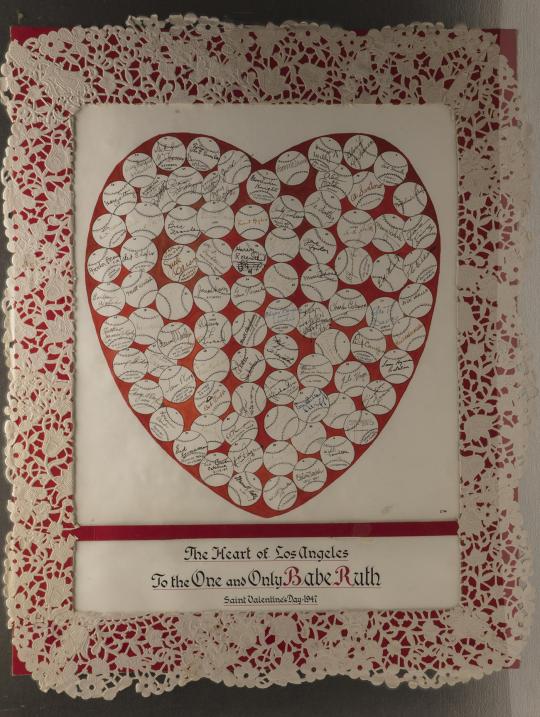

For 20 cents – about two dollars today – lawyer-turned-journalist-turned-syndicate-man Christy Walsh put a 27-inch, doily-encrusted slab of cardboard in the mail. By airmail mind you, no expenses spared, because the board had somewhere important to be: It was carrying the Heart of Los Angeles to the one and only Babe Ruth, who was undergoing treatment at the French Hospital in Manhattan. It was an oversized and slightly belated Valentine’s Day card, posted around 4 p.m. on Feb. 15, 1947.

The Heart of Los Angeles carried signatures from Hollywood moguls, statesmen and stars, from Bing Crosby and Connie Mack to a federal judge and the city sheriff. Among all those powerful men, two common folks slipped their well-wishes in, too. Mail handlers J. Thomas and J. Wood scribbled their names on the board during its shipment, along with a quick message: “Happy Valentine, Babe.”

Babe Ruth needs no introduction, but Walter Christy Walsh might. In the defense of those who are unfamiliar with him, a majority of his work was done under the names of other men. Walsh maneuvered his way into Major League Baseball as a reporter and ghostwriter, and once there, he pioneered the role of the sports agent. Players he signed to exclusive contracts with the Christy Walsh Syndicate were guaranteed articles under their bylines and lucrative promotion in return for a percentage of profits that would have made today’s agents blush.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Walsh attended St. Vincent’s College – known today as Loyola Marymount – where he studied law, graduating in 1911 and passing the bar in 1915. He never saw the inside of a courtroom, however. After graduating, he worked for the Los Angeles Express and Herald as something in between a go-fer and a journalist. His favorite part of newspaper work was cartooning, especially for the sports page. He was a self-taught artist, pulling together likenesses of famous ballplayers from wobbly cobbles of lines. Though not quite a poor cartoonist, he had a better way with words, carrying his reader along with all the cadence of the coming Jazz Age.

His written and drawn works are bright with lighthearted humor, but by all accounts, their creator had a serious head planted firmly on capable shoulders. He was born in St. Louis in 1891 and took his Midwestern-Irish-Catholic heritage, or what he referred to as ‘horse and buggy’ values, very seriously. Walsh himself had lived in California since he could walk, but he hardly let it show. In nearly every photo of the man, his clothes are pressed and buttoned; even in gym clothes, his collar was tight around his neck. It looks as though he parted his slicked-back hair with the help of a ruler. More than any of his other renaissance-man ventures, Walsh was a businessman, and he dressed the part.

When he lost his job at an advertising agency due to whispers of a lasting depression in 1921, he pulled together a no-collateral loan and a few comrades to build his own ghostwriters’ syndicate. Though he would finish the year with eight dollars in his bank account, Walsh’s $2,000 gamble was rewarded. He would claim mastery over the names of Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Rogers Hornsby and Lou Gehrig, among others, and the loan was paid in full before it was due. His clients got a consistent flow of well-written material to sell to newspapers across the nation, and Walsh and his men got a quarter or even half of the profits.

This is the sort of thing that sounds overly simplistic today, but it was at the cutting-edge of a rapidly developing field at its time. Televised baseball was still another few decades out, and what few radio broadcasts of games there were tended to be about colorful as a box score. Aside from the lucky few who lived in the shadow of a ballpark, the newspaper was the closest most Americans would ever be to getting to know their heroes. Walsh made sure that everyone had that access – to a clean, carefully-crafted version of them, of course – and it made him and his writers rich.

The phantoms of the Syndicate were stars in their own right. Ford C. Frick, father of the Hall, was Gehrig’s ghost. Walsh’s squad of 34 writers eventually amassed more than a hundred thousand dollars in sales. Four of them broke into the $10,000 Club: Bozeman Bulger, Neal O’Hara, James Isaminger, and, certainly, Frick. The syndicate once made nearly that much on a single story alone with the help of Connie Mack’s byline during the 1929 ‘Mack Attack’ World Series.

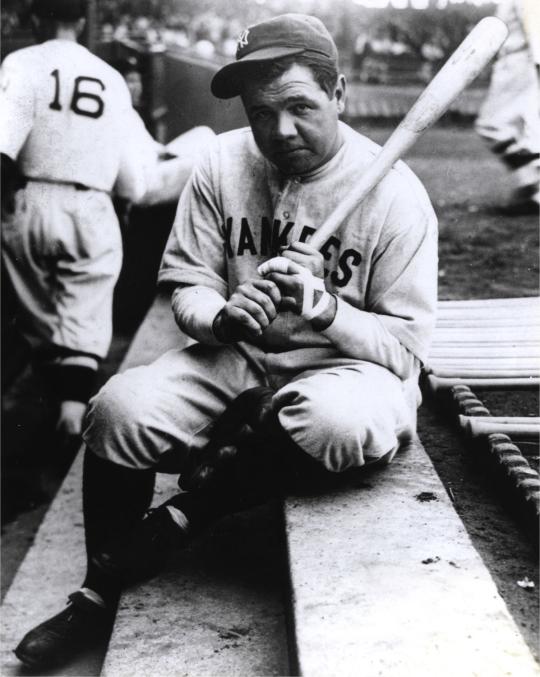

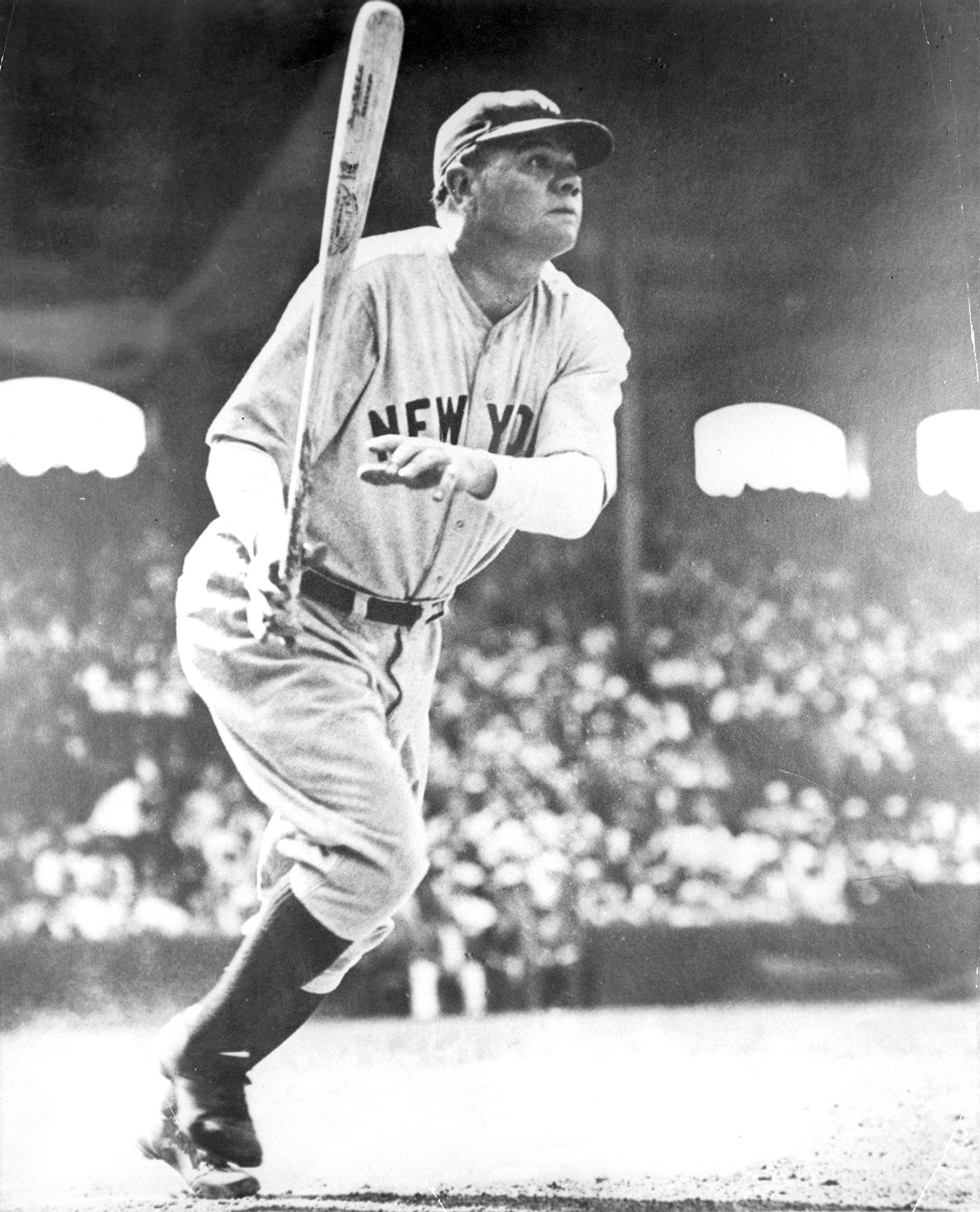

George Herman Ruth was undoubtedly the Syndicate’s crown jewel, though, Walsh’s first and greatest. How Walsh and Ruth met is less than clear; Walsh never told the same story twice, and Ruth never told the story at all. In his 1937 memoir, Adios to Ghosts, Walsh spins the tale of how he had been staking out Ruth’s luxury hotel apartment for days when he finally got his break. Walsh overheard the owner of the deli that Ruth frequently bemoan the absence of his beer boy after the ballplayer had called down for a case. How would they get the Bambino his bottles, now? Walsh swiped the cart and headed up to peddle both the drink and a contract. The beer must have sweetened the deal, as Ruth signed over his byline to Walsh for the entirety of the 1921 season.

“I shall never forget the expression on Babe Ruth’s face when I handed him a check for $1,000 at the Polo grounds [on Opening Day],” Walsh recounted. “I was not obligated to remit for 90 days, but here was a fellow who had been skinned so many times by strangers that I felt the way to win his confidence was to pay in advance.” At the time, the Babe had been skinned so recently it likely still bled – just the previous October, Ruth was stranded, penniless in Havana. He had been swindled out of everything he had earned during an All-Star tour in Cuba. “The plan worked and our mutual confidence has lasted throughout many years. However, to this day, he doesn’t know that I had to borrow $1,000 from a bank at six per cent,” Walsh concluded. Like his other bets, this ploy eventually paid for itself.

Under Walsh’s direction, Ruth made almost half a million dollars in endorsements and investments alone, from which Walsh collected a generous cut. One of the most famous of these was Babe Ruth’s All America Athletic Underwear Line. Ruth was once paid a thousand dollars just to appear in the presence of the product. He made about as much as the average American did in a year by standing next to some underwear for an hour. In addition to making Ruth rich, Walsh did his best to keep him that way. It was a tall order – Ruth went through fine silks like tissue paper and gave waiters their week’s wage in tips – but Walsh was as cautious as Ruth was indulgent. He arranged a foolproof trust to provide for him after he could no longer swing for his meal.

Eventually, the Syndicate alone could not bear the massive weight of the Babe’s dealings, and Christy Walsh Management was put together to pick up the slack. By then, Christy Walsh’s byline was a money-maker in its own right. It was tacked on the backs of baseball cards, books, cartoons, and the credit reels of Hollywood films. “By arrangement with Christy Walsh” was a reliable phrase to fans and buyers, even if the old ghostwriter was ghosted as much as an actual ballplayer at that point.

Walsh did more than just manage Ruth’s business, though. He made the Babe’s personal affairs as much of his concern as his financial ones. He did his best to keep Ruth’s image family friendly, and when that failed, he was there to pull together charity events or photo opportunities in order to clean up after him. “We were known as press agents until someone started using fancy titles like ‘Public Relations counselor,’” Walsh said.

Though the two men were only a few years apart, the older Walsh assumed a familial kind of responsibility for Ruth, who never had such a relation of his own. “Bustin’ Babe is keeping in good shape under the watchful eye of Christy Walsh,” a 1927 article explains. “Mr. Walsh has filled the role of ‘big brother’ to Ruth, and the latter has wisely bowed to his unfailing judgement.” One wonders if Walsh took the ghost back up for that last bit. He and Ruth would remain inseparable until they parted amicably in 1938, around the time that Ruth parted from baseball. As a characteristic farewell gift, Walsh sent him an itemized list documenting “17 years of congenial and mutually profitable relations.” In spite of Ruth’s very best efforts, Walsh had maintained the Babe’s coffers well enough for a comfortable retirement.

Unfortunately, Ruth would not live to enjoy much of it. He became ill in late 1946. Doctors at the French Hospital would eventually diagnose him with nasopharyngeal carcinoma, or cancer of the upper throat. The tumor was in a dangerous spot, enveloping his carotid artery, and surgery could not remove it. Radiation and experimental medicine helped manage the disease, but that was all the doctors could do: manage. The French Hospital discharged him to spend his remaining time at home in February of 1947, which seems to explain why Walsh’s tardy Valentine was forwarded directly to Ruth’s personal address.

The card speaks to the unexpected sturdiness of the relationship between Christy Walsh and Babe Ruth. By 1947, Walsh had been out of baseball and Ruth’s shadow for a decade – he was a consultant for the film industry and a football coach, tucked away in a North Hollywood home – but he still managed to organize one last deal for the Babe. While this particular set of important signatures didn’t net Ruth any profit, it still seemed to hold some value for him. It was one of the many objects from the Ruth Collection, a massive assemblage of gear and personal effects that helped jumpstart the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. One way or another, Ruth felt the need to keep his old partner’s well-wishes around until the end.

Hannah Blank was the 2022 collections intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development