- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Phil Douglas’ battle with baseball in 1922 derailed a stellar career

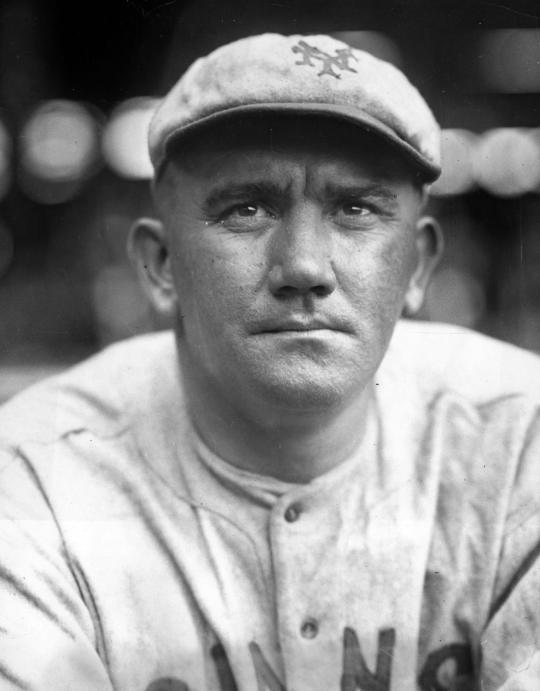

#GoingDeep: Phil Douglas’ battle with baseball in 1922 derailed a stellar career

Shufflin’ Phil Douglas, his world caving in around him after having just learned he was banned from ever playing in organized baseball again, sat sobbing in his hotel room. Despite his protestations, this horrendous life turn – he knew deep down – was of his own making.

“Here I am without a cent with everybody spotting me as a traitor and a deserter and all that sort of bunk,” arguably the top pitcher in the game, with tears in his eyes, told a reporter from his room at Pittsburgh’s Hotel Schenley. “I’m as innocent as a child.”

One-hundred years ago, the veteran righty, arguably one of the game’s top moundsmen at the time, found himself prohibited from participating in the game he loved. It was the end result of a journey that featured multiple future Hall of Famers – and denied fans the chance to cheer for one of the game’s most colorful characters.

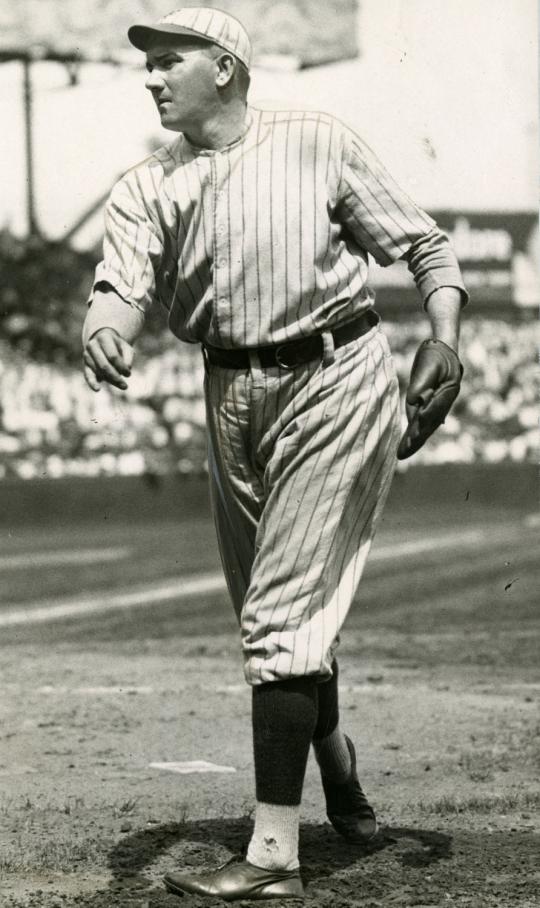

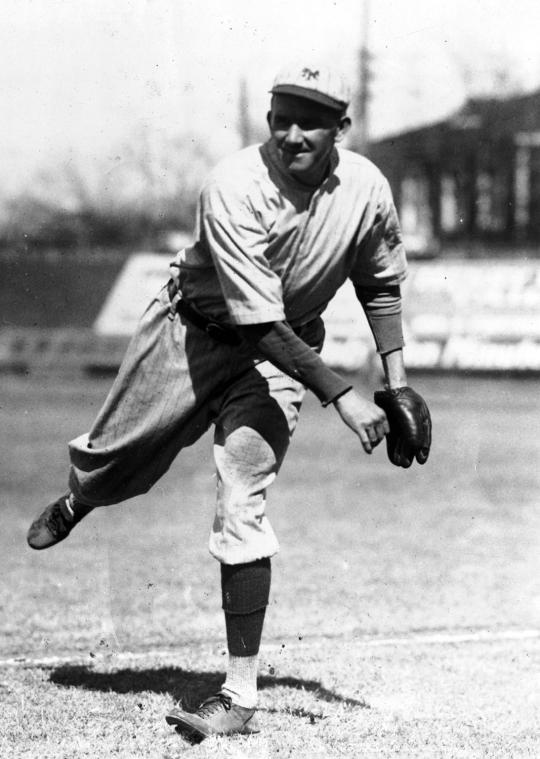

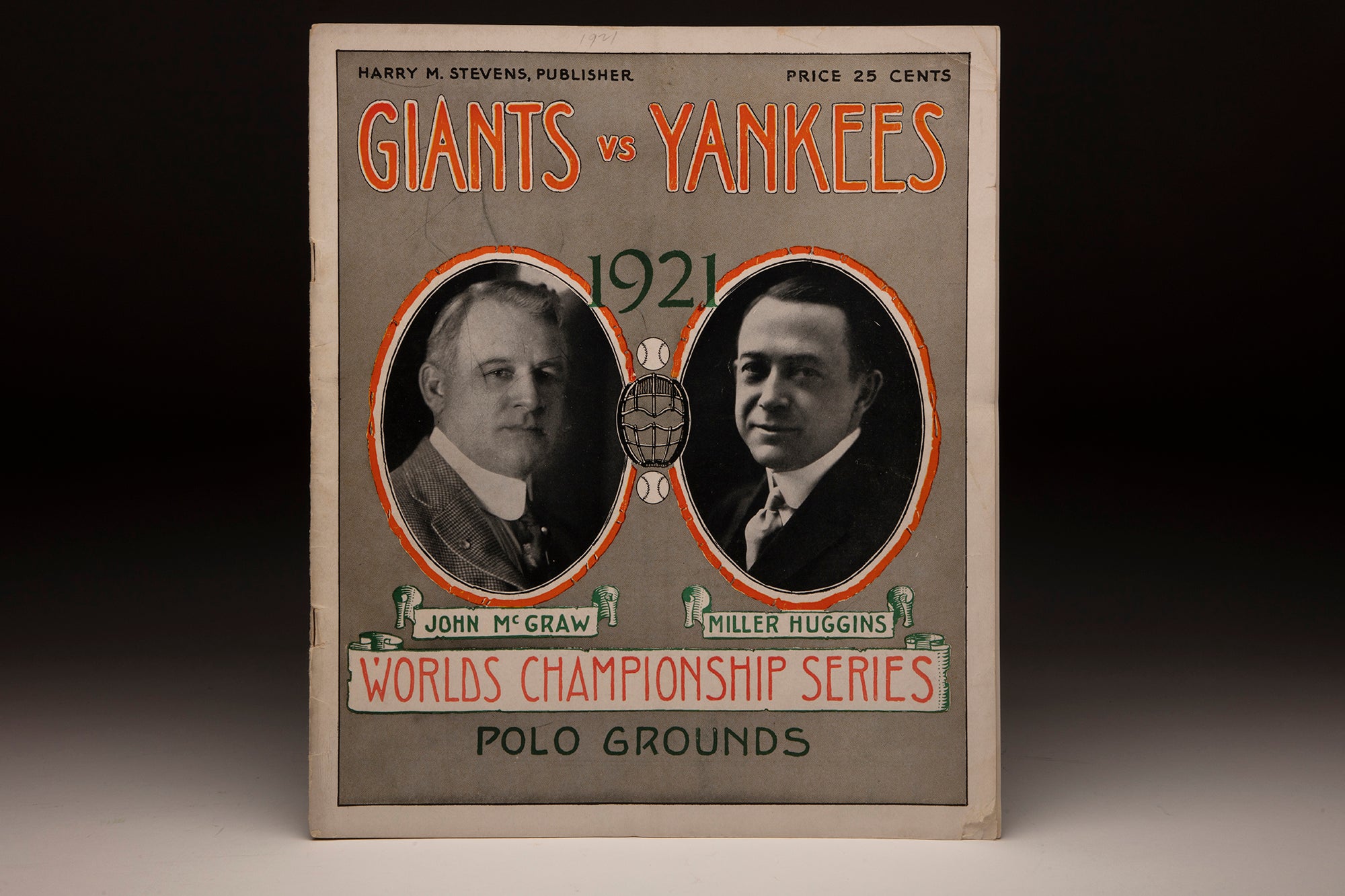

In 1922, the Tennessee-raised Douglas, a savvy hurler with speed and a sharp-breaking spitball, was coming off a stellar 15-win season with the National League pennant-winning New York Giants. The powerfully built righty, who stood 6-foot-3, then went on to win two games in the World Series to help defeat the New York Yankees – a co-tenant with the Giants of the Polo Grounds before they moved into the newly built Yankee Stadium in 1923.

But the player nicknamed “Shufflin’ Phil” by sportswriters because of his slouching gait never reached the diamond heights his ability warranted because, ultimately, he was his own worst enemy. Maybe it’s the reason his ball-playing brethren often called Douglas “a right-handed southpaw” – referencing the long-held belief that left-handed pitchers are unpredictable.

Acquired by the Giants from the Chicago Cubs in midseason 1919, Douglas was a durable and successful pitcher in the Windy City who led the big leagues with 51 games pitched in 1917.

While 1922 would prove to be one of his most successful seasons, it was during Spring Training that year that reports began to surface that both Douglas and Jesse Barnes, heroes of the 1921 Fall Classic due to their two wins apiece, were publically put on the market without explanation by the Giants.

“We are not ready to make any announcement about the matter now,” said Giants secretary James J. Tierney to the press in February 1922, “but you may look for interesting news in a few days.”

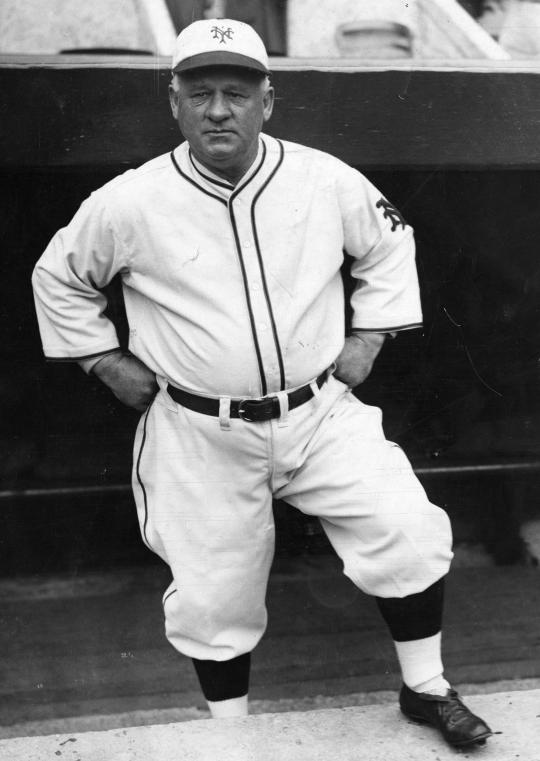

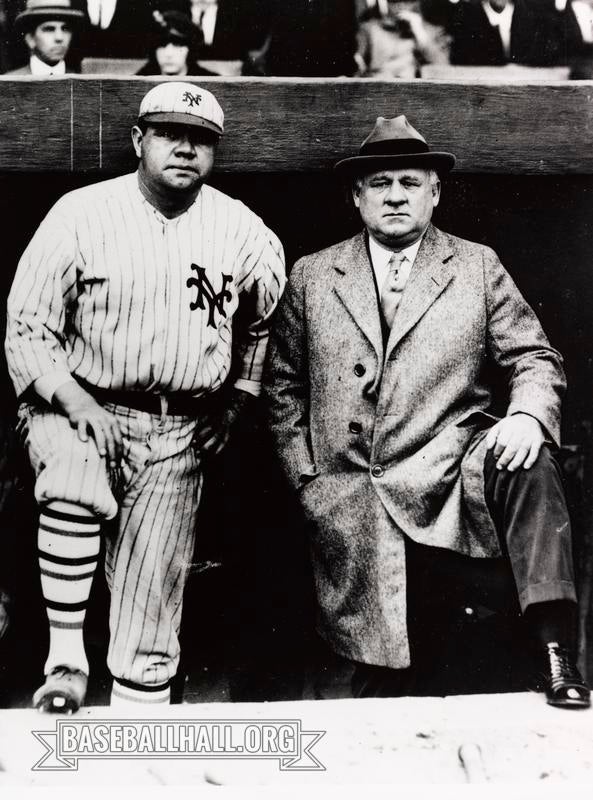

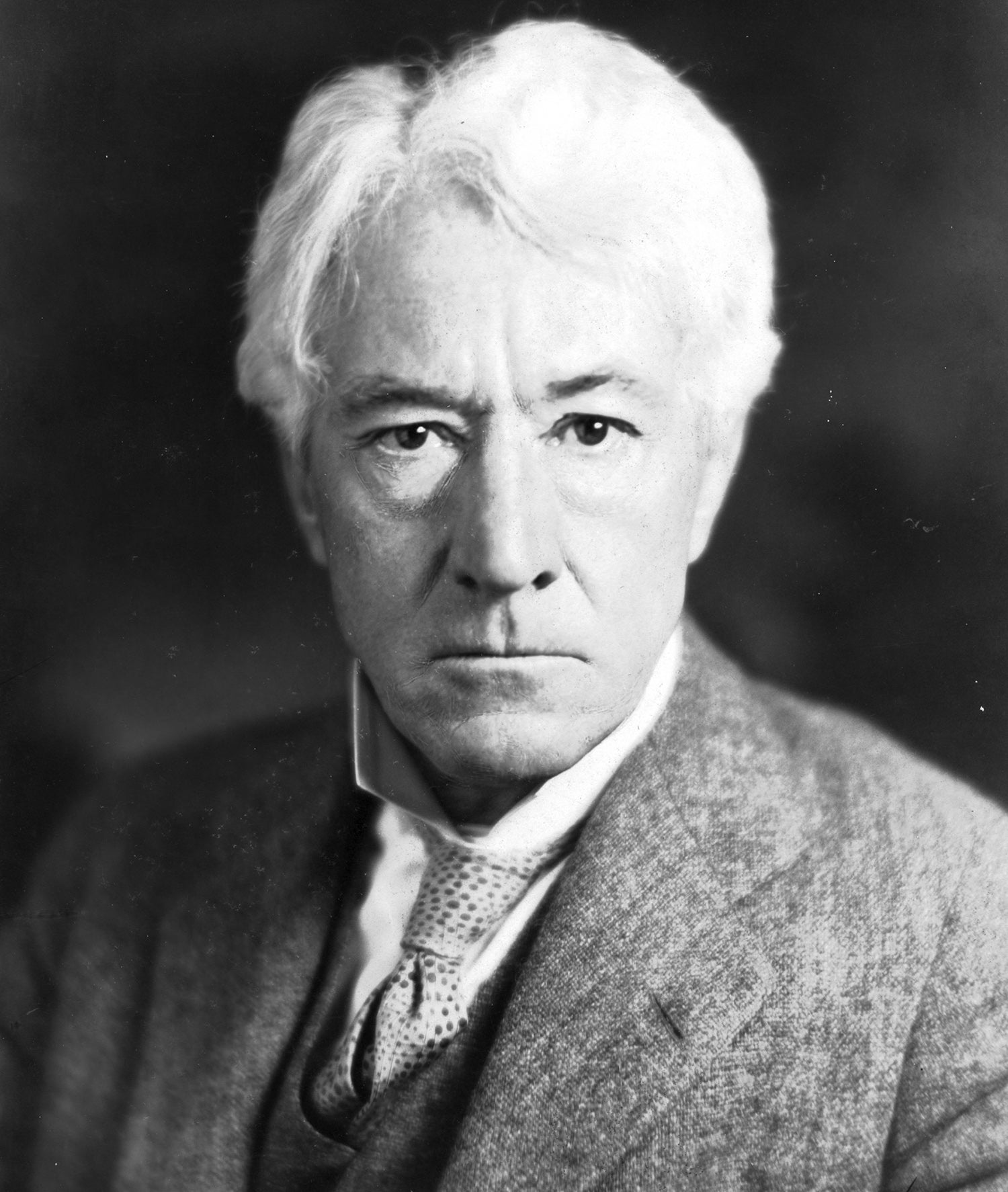

Speculation regarding Douglas’ sudden availability centered on his clashes with manager John McGraw, the future Hall of Famer, and the fact that he was considered, according to baseball writers, a “bad actor” now and again during the season. Both pitchers would be gone by summer – one traded (Barnes) and one banished (Douglas).

Continuing the success he enjoyed in 1921, “Shufflin’ Phil” got off to a rousing start in ’22, compiling an 11-4 won-loss record and a league-leading 2.63 ERA by mid-August for the first-place Giants. But then, due to his own shortsighted and ill-conceived solution to a self-inflicted wound, he was sent home in disgrace.

While the baseball world knew of his ever-changing disposition and checkered career to that point – he’d worn five different big league uniforms because managers grew tired of his antics – still there was shock when the news broke that Douglas had been forced out of baseball under a black cloud.

With the Giants in Pittsburgh in the midst of a three-game series, on Aug. 16, 1922, Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis charged Douglas with writing a letter to an opposing player offering to desert the Giants in order to hurt the team’s pennant chances.

“Phil Douglas has been put on the permanent ineligible list by the New York National League baseball club for writing a letter to a member of a competing team offering to desert his club if it would make it worth his while,” read the Landis statement. “Douglas does not deny he wrote the letter. We went through with this at the solicitation of Mr. Heydler, president of the National League.”

As far as McGraw, 49, was concerned: “The Giants are glad to get rid of Douglas. His erratic actions have given me many gray hairs but I could not have believed that he would do anything like this. Now we have proof in his handwriting and in the words of persons who overheard his telephone conversations.”

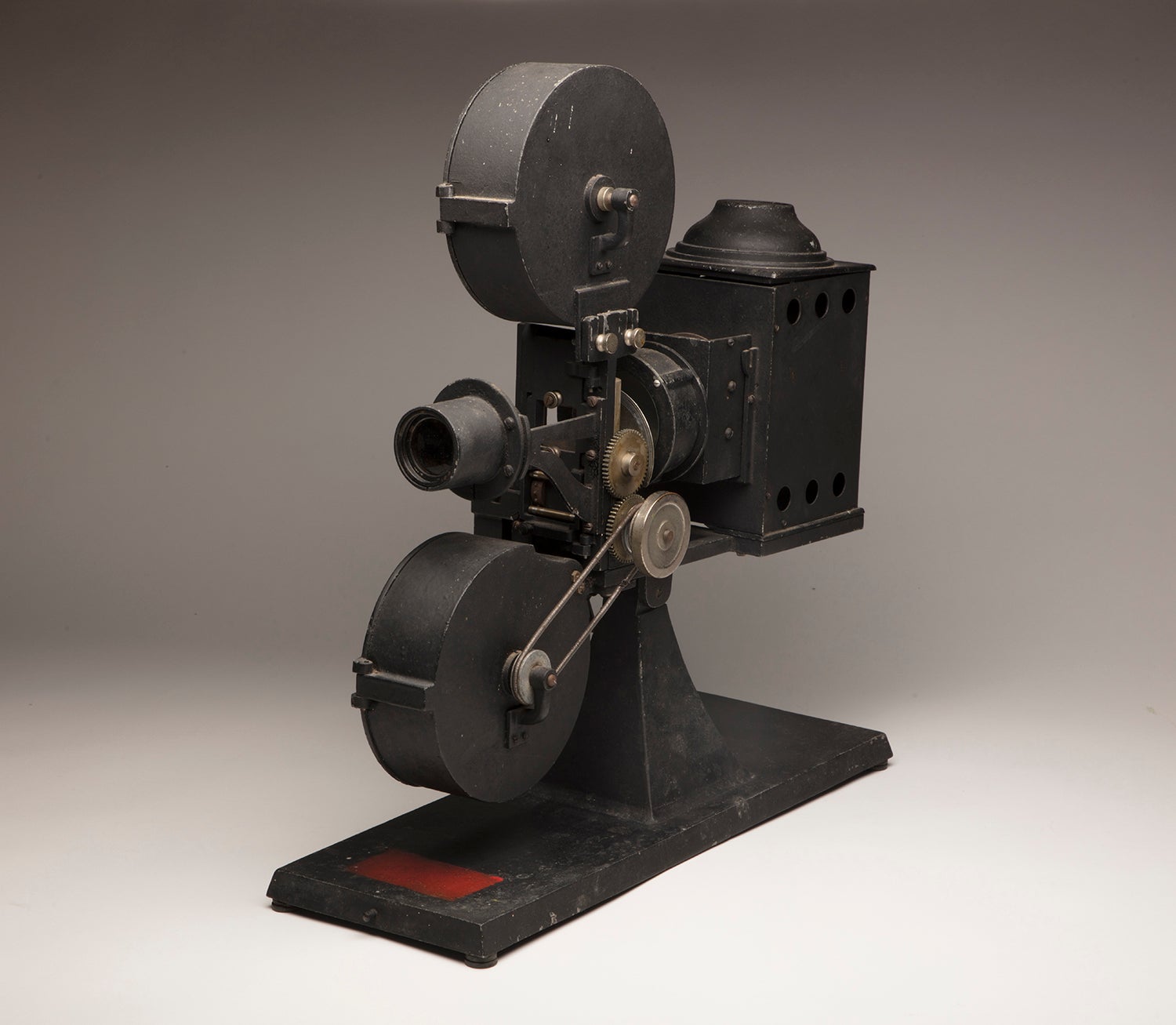

The letter referred to in this case, written on Aug. 7, 1922, was allegedly mailed to outfielder Les Mann of the St. Louis Cardinals, a team battling the Giants for first-place. Mann later became one of the earliest adopters of video technology as a training tool, and his Mannscope projector is now part of the Hall of Fame collection.

But from the time he received Douglas’ letter, Mann – who played with Douglas with the Cubs from 1917 to 1919 – refused to discuss the Douglas case or admit that he ever received the communiqué from Douglas.

The infamous letter, as reported in the newspapers, reads as follows:

“To Dear Les –

“I want to leave here but I want some inducement. I don’t want this guy to win the pennant, and I feel if I stay here I will win it for him. You know how I can pitch and win. So you see the fellows, and if you want to, send a man over here with the goods and I will leave for home on the next train. Send him to my house so nobody will know and send him at night.

“I am living at 145 Wadsworth Ave. apartment 1R. Nobody will ever know. I will go down to fishing camp and stay there. I am asking you this way so there cannot be any trouble to anyone. Call me up if you are sending a man. Wadsworth 3210, and if I am not there, just tell Mrs. Douglas. Do this right away. Let me know. Regards to all.

“Phil Douglas”

A wire service reporter tracked down Douglas later the day he was kicked out of baseball in his Pittsburgh hotel room. Douglas placed the blame for his banishment from baseball on McGraw.

After alleging that McGraw “had it in for him,” Douglas, 32, saw Mugsy stick his head into the hotel room. “Get the h--- out of here, you big bum,” Douglas yelled at McGraw.

“That’s him,” Douglas said. “That’s the guy that threw me out for something I don’t know anything about.”

“What makes me so mad,” said Douglas with tears in his eyes, “is that Mac won’t even give me my pay. I don’t know how I’m going to get out of here unless I get some money and I’m ashamed to wire my wife.”

While searching for answers, alcohol was always a contributing factors in many if not all of Douglas’ woes during these years. He became as noted for his excessive drinking as for his pitching – and he was reportedly quite efficient at both. As one sportswriter put it, “His great shortcoming was endeavoring to lap up all the firewater in every village he visited.”

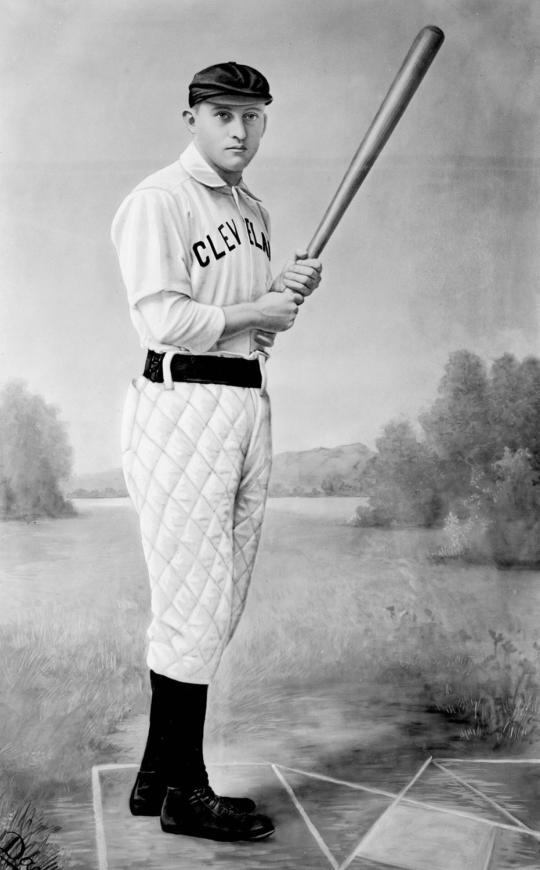

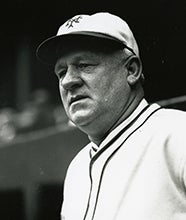

In order to inhibit Douglas’ urges toward liquor, McGraw assigned Giants scout Jesse “The Crab” Burkett, a star outfielder in the 1890s who would be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1946, as a guardian for has sometimes unreliable pitcher during the second half of the 1922 season. It was Burkett’s busy task to see that his charge and road roommate did not partake.

“And to top it all he hired Jess Burkett to follow me around, and that was anything but pleasant,” Douglas said years later. “All of this caused me to want to leave the New York ball club.”

Not only did Douglas and Burkett sit side by side through many movies, but, according to Giants catcher Frank Snyder: “They probably drank more ice cream sodas together than any two grown men in history, before Doug got away on his last binge.”

The “last binge” turned out to be the linchpin for the drama that ensued. With Burkett doing such a good job, Douglas grew to detest him. But finally, in what proved to be his final game ever, Douglas eluded his guardian after giving up five runs in seven innings in a 7-0 loss to the visiting Pittsburgh Pirates July 30, 1922.

Soon, a despondent Douglas, back in New York and desperate for a drink, went missing. He ended up at a friend’s Upper West Side apartment, got drunk and passed out. Then, as Douglas told it days later, detectives dragged him from the apartment and took him to a sanitarium, where he was held until Aug. 5.

Upon his release from the sanitarium, Douglas said, he believed McGraw had suspended him.

“On Saturday, Aug. 5, thinking that I had been dismissed from the team,” Douglas said. “I went to the Polo Grounds and wrote the letter to Mann, who was then in Boston with the St. Louis club. Shortly afterward McGraw called me into his office in the clubhouse and bawled me out. He called me the most vile names, but said nothing about firing me from the team,” Douglas said. “I then realize that I was still to be retained on the club and that night I phoned to Mann at the hotel in Boston where the Cardinals were staying and begged him to tear up the letter. I told him that I had made a bad mistake in writing it and that I hadn't been fired from the Giants. Mann finally agreed to tear up the letter, but instead of that he turned it over to Branch Rickey, who immediately notified McGraw. I heard nothing more of the letter until I was called into McGraw's room in the Schenley in Pittsburgh.

“I was desperate when I wrote the letter. I thought that I had been fired from the club when they suspended me, fined me and then tried to make me pay the bill for the sanitarium as well as for the taxi in which they took me there. I was sore at McGraw because he gave me a rotten deal. I had to make my living some way, so I then sat down and wrote the letter to Mann.”

McGraw’s version of event, as could be expected, varied widely from Douglas’ take on the sordid episode.

“After the game on July 31, Douglas disappeared and could not be found for several days. However, about the middle of the week we got trace of him. I told Jesse Burkett to go up and get Douglas. According to what Burkett told me over the phone after the game that day, Jesse and two plain clothes men went to the apartment and found Douglas dead to the world. They made him leave the place at once. They carried Douglas to a cab and took him to a sanitarium on Central Park West.

“That night I went down to see Douglas and talked briefly with him. I told Phil to get into condition to pitch and everything would be all right. Not until the next Monday morning, Aug. 7, would the doctors let him leave. That day there was no game and I called him to my office for a talk. I told him he was fined $100 and his pay during his absence, but if he would get into condition every cent would be remitted. He had already overdrawn his account by $200 and said that he was dead broke. So I ordered that $200 be sent to Mrs. Douglas, along with a $90 check for the rent.

“Phil told me how grateful he was and what I good friend I was. He vowed he would pitch the next day and keep in condition to show his gratitude. Then he went into the clubhouse and wrote that letter, offering to sell his team out for money. It was written on club stationary at a little desk in a room where other players were. That night Douglas vanished again and was seen no more until ready to leave for Pittsburgh last Monday night.”

Commissioner Landis, who had been hired to clean up baseball only a few years earlier due to the Black Sox Scandal, acted quickly and decisively in regards to Douglas – declaring him ineligible.

The Giants would go on to win their second consecutive World Series in 1922, again over the Yankees. Life for Douglas, however, was tough over the next three decades mainly spent in poverty. In the years following his banishment from organized ball, Douglas pitched for various semipro clubs with little success. He would also occasionally appear in the newspapers after being arrested on various drunk and disorderly charges.

“Under the conditions, I think I have been treated unfairly, but I have not the means to fight it,” a broke and discouraged Douglas told a sportswriter in 1936. “It has worked many hardships and caused me many heartaches, this hanging over my good name. I love baseball and, as you know, was always in there for a lot of games every year.

“I surely need help, and any other information I can give I’ll be glad to do so. Nothing would do me more good than to have a chance to come back in life, and I, as well as my family, will appreciate anything you can do for me.”

After a series of strokes, a bedridden and nearly destitute, Douglas passed away on Aug. 1, 1952, at the age of 62. He spent his last two decades living in a log cabin on the side of a cedar covered hill in Whitwell in southern Tennessee. Neighbors claimed that Douglas was a good citizen who sang tenor in the church choir and was generally at peace with the world.

In 1990, an unsuccessful attempt to lift Douglas’ banishment from baseball was made by his family. In a letter released later that year, then Commissioner Fay Vincent refused to open the case, contending there was not enough evidence to reverse Landis’ decision. On May 13, 2025, Commissioner Rob Manfred issued a policy decision that removed Douglas and 16 other deceased individuals from the permanently ineligible list.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. This story was updated on May 13, 2025.