- Home

- Our Stories

- Eddie Leonard’s Loving Cup for John McGraw

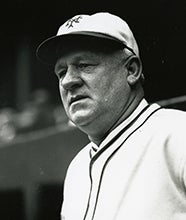

Eddie Leonard’s Loving Cup for John McGraw

It was Monday, July 28, 1941, an off-day for all major league clubs. With no game to take in, longtime New York baseball fan Eddie Leonard took the opportunity to run an errand. He left his apartment at 120 West 44th Street and made the short, four-block walk to his dentist’s office at Broadway and West 41st.

After dropping off his dentures for repair, the 70-year-old Leonard wandered the streets of midtown Manhattan. Fatigued by the sweltering heat and stifling humidity, he eventually found himself in front of the Hotel Imperial at Broadway and West 31st—a place he knew well.

Back in his heyday, when Leonard was heralded as the greatest minstrel singer and black-face comedian of his time, the hotel had been his home. But now his days as a vaudeville headliner were long in the past. Unrecognized by the hotel staff, he checked in for $3, headed up to a sixth floor bedroom, folded his clothes neatly on a chair, lay down in bed, and died.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

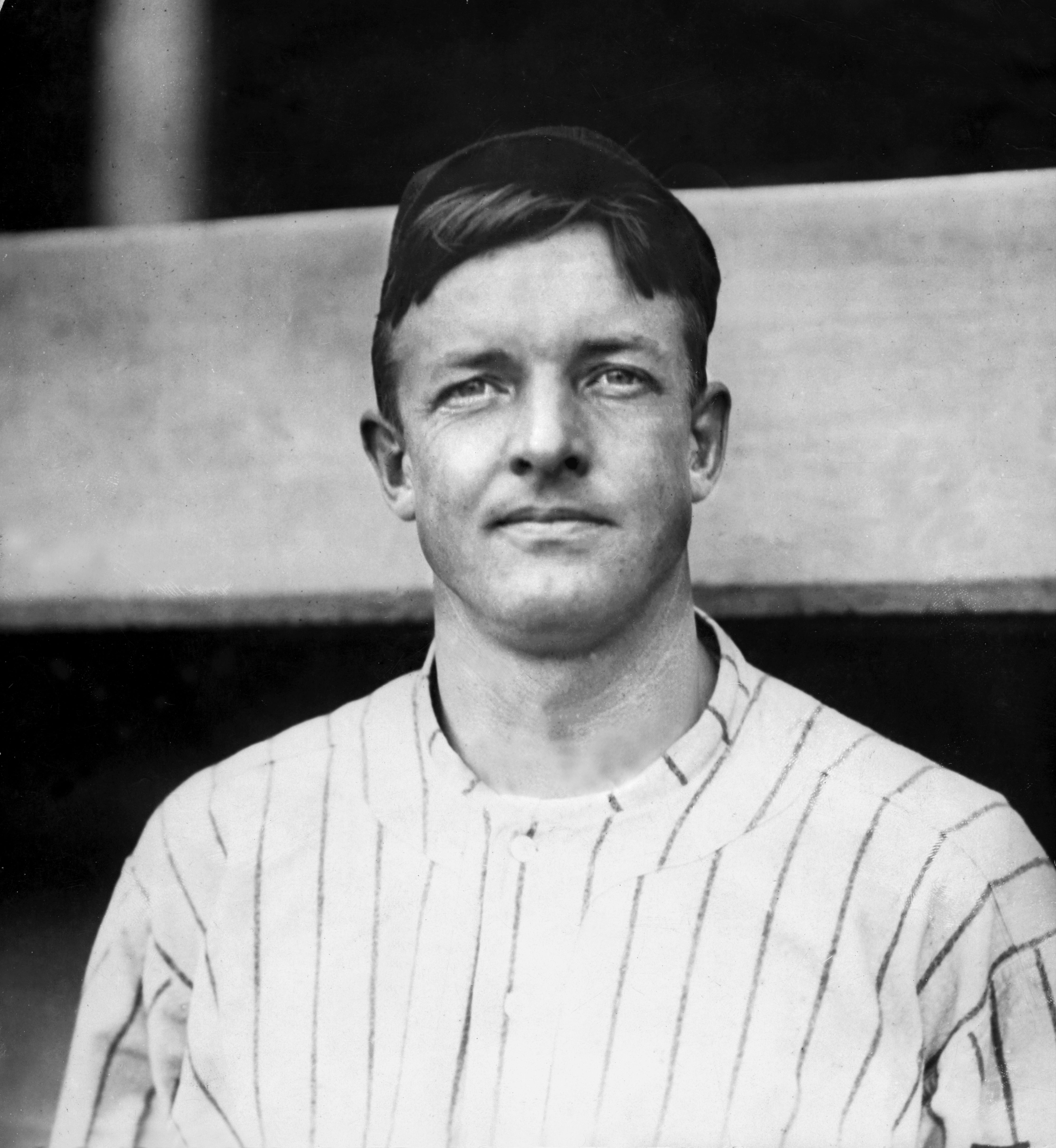

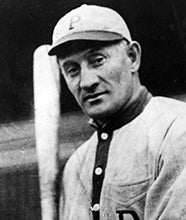

Born Lemuel Golden “Dots” Toney in Richmond, Virginia, in 1870, Leonard spent his teenage years working in iron mills, singing and dancing on local minstrel stages, and playing baseball. The man who later took the stage name of Eddie Leonard never grew tired of telling stories of his days on the ball field. A particular favorite was the story of how he abandoned baseball for a life in the theater.

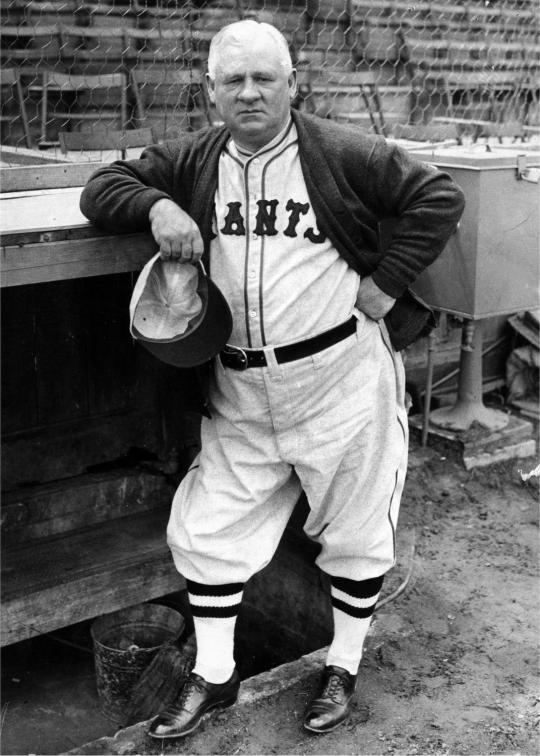

“I remember way back when,” said Leonard in a 1923 interview with the San Francisco Examiner. “I was in the old Virginia State League then. Back in 1897 it was. John McGraw was with the Baltimore Orioles then “He gave me a chance to break into the big time of baseball. I got my tryout, but I didn’t make the grade. Soon after that McGraw met George Primrose of Primrose and West, famous minstrels in New York, and told him something like this: ‘I’ve got a ballplayer that, as an infielder, is a fine singer and dancer. Better give him a job with your company. He’ll never make a ballplayer.’”

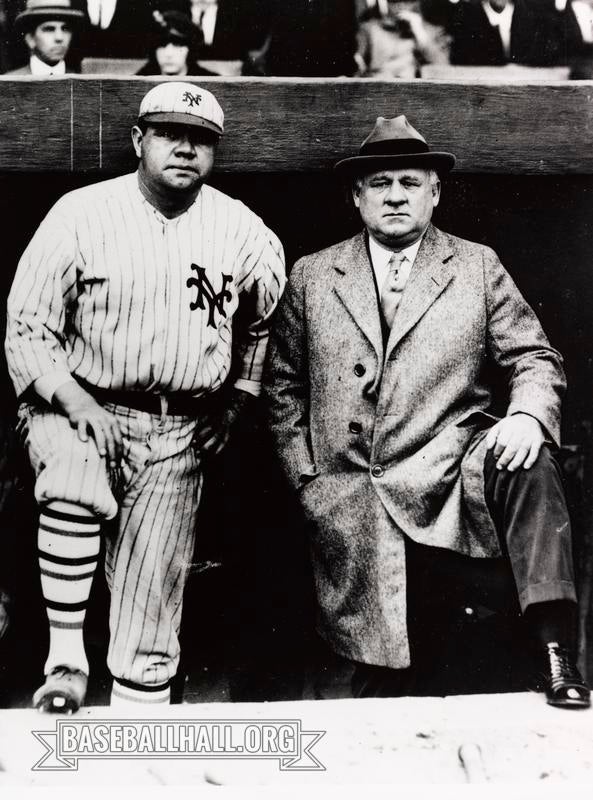

The entertainer did indeed make it ... as a vaudevillian, eventually earning the title of America’s greatest minstrel. Still, he never lost his love for the National Pastime, regularly attending big league games and hobnobbing with future Hall of Famers such as Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Bill Klem, and Babe Ruth. But Leonard’s true loves were the Giants and John McGraw.

Indeed, this obsession was so complete that, according to the Kansas City Gazette Globe in 1917, “the vaudeville houses in New York want his services, but he will accept no engagements unless arrangements are made whereby he can play on the program early enough to give him time to reach the Polo Grounds before the first swing of the bat.”

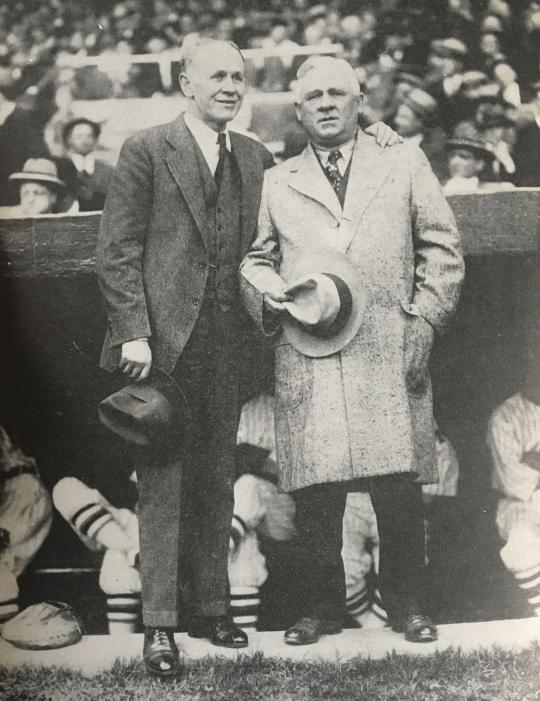

Three decades before Leonard passed away, the Giants captured the 1911 National League pennant. On Oct. 15, in honor of their achievement, admiring fans feted the ball players with a testimonial vaudeville performance at the New York Theatre.

The stars on the bill that evening included entertainer extraordinaire George M. Cohan, celebrated singer/actress Lillian Russell, former heavyweight boxing champion James J. Corbett, and Leonard.

Two years later, Leonard parlayed his connections with McGraw into a role on the diamond, taking part in practices with the Giants prior to New York’s 1913 World Series matchup against the Philadelphia Athletics. But the vaudeville star was unable to attend the Fall Classic as he was booked at Baltimore’s Maryland Theatre along with Jack Norworth, the singer-songwriter who penned the lyrics to “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” in 1908. Fortunately, as reported in the Baltimore Sun, “When [Leonard] heard that the world's series results will be announced daily from the stage of the Maryland he was like a schoolboy told that he might have a week’s vacation.”

In 1916, McGraw’s Giants started the season dismally, winning just two of their first 15 games. But when they left New York for an extended road trip, something clicked. The club won 19 of their next 21 games, including a still-standing record of 17 straight road victories. Thrilled by the stunning achievement of his beloved Giants, Leonard honored each member of the club with a silver cup some 12 inches in height, engraved with the player’s name, and adorned with the words “Presented to the Record Breaking Giants by Eddie Leonard, June 2, 1916.”

For McGraw, Leonard bestowed a loving cup three-times the size of the others, crowned with a silver baseball resting atop three crossed bats, and decorated with the proclamation:

Presented to

“The Napoleon of Baseball”

John J. McGraw

Manager

“Record Breaking Giants”

by

Eddie Leonard

June 2, 1916

The ornate trophy is preserved at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, having been donated to the Museum in memory of Richard J. and Joan M. Brown in 2019.

When McGraw passed away in late February of 1934, thousands gathered at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City for the funeral of the former Giants manager.

Along with the numerous baseball dignitaries at the service, other celebrities in attendance included humorist Will Rogers, billiards world champion Willie Hoppe, famed thoroughbred racehorse trainer Max Hirsch, and, of course, Leonard.

“I took John’s death seriously,” wrote Leonard in his 1934 autobiography What a Life, I’m Telling You. “To me he was just like a brother.”

Some seven years later, when Leonard failed to return home that hot summer evening in 1941, his wife Mabel reported him missing. She told the police that her husband of 32 years could be identified by a lifetime pass to the Polo Grounds that he kept with him at all times, a gift from his good friend John McGraw.

The next day, Leonard’s lifeless body was discovered in his hotel room. Newspapers reported that the pass was found clutched in his hand.

In death, as in life, Eddie Leonard held fast to his love for baseball and his cherished relationship with John McGraw.

Tom Shieber is the senior curator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum