- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Sol White's royal prose

#GoingDeep: Sol White's royal prose

Sol White spent most of his life waiting for that day on April 15, 1947, when a Black man crossed the metaphorical color line in Major League Baseball and again played ball with white teammates.

For White, then 78, the wait had lasted a half century.

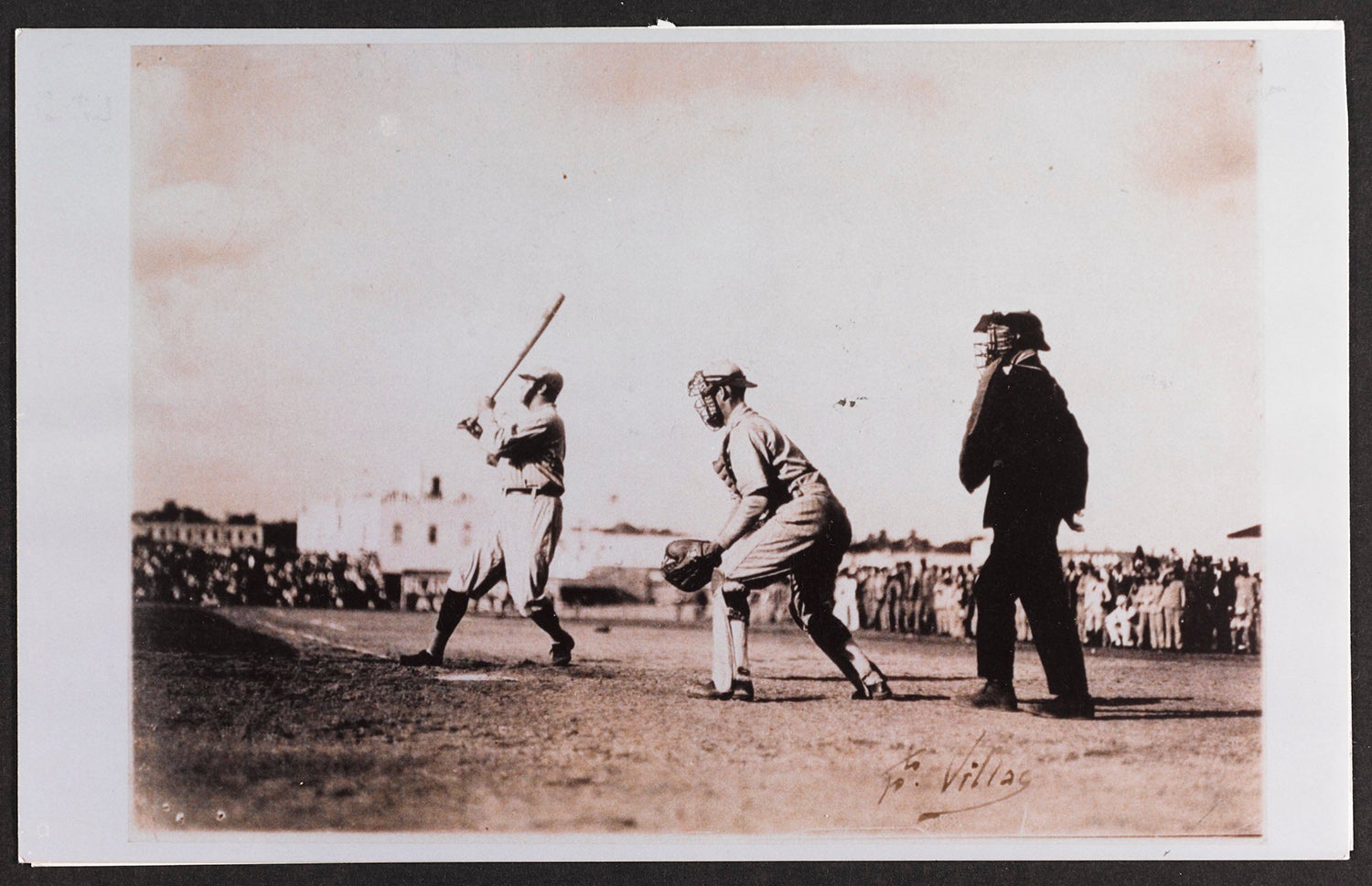

But when he was younger, White had tasted integrated baseball. In the late 1800s, he and a handful of other Black men played with whites before team owners came to a “Gentleman’s Agreement” on a color line.

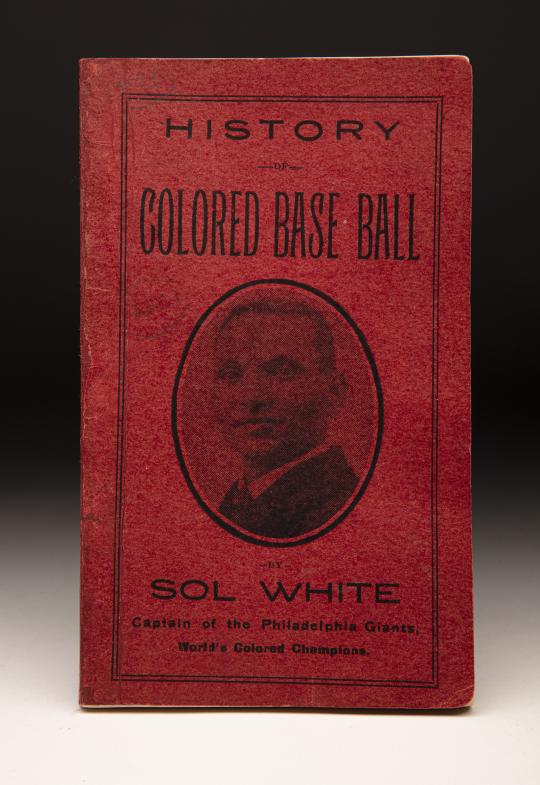

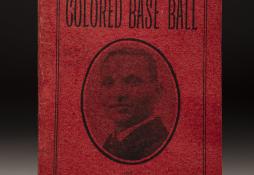

Now, in 1947, White was an old man, an almost forgotten old man. His career as a player and manager was scarcely a footnote, and it might well have been forgotten altogether were it not for a singular work of nonfiction from 1907: “History of Colored Base Ball.”

Who wrote the book?

Sol White.

“Still to this day, his book is one of the best resources we have to understanding the early participation of African Americans in baseball,” said Leslie Heaphy, associate professor of history at Kent State University and one of the foremost authorities on Black baseball. “There’s no better place to start.”

Larry Lester, a noted researcher into the history of Blacks in baseball, echoed Heaphy’s view: “Sol White’s ‘History of Colored Base Ball’ is the only legitimate document out there that recognizes the early days of the Black game.”

But Lester and Heaphy, both members of the Museum’s Black Baseball Initiative advisory committee, wondered whether diehard fans will remember White, who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2006, as more of a writer than as a ballplayer. Probably so, Heaphy said. White didn’t use his book to trumpet his career, which started and ended decades before Jackie Robinson took the field with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

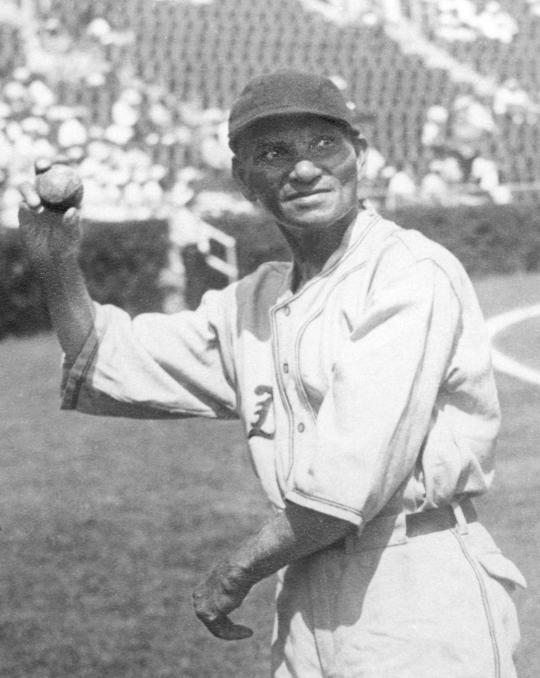

The slight of White’s baseball skills is unwarranted. Lester said his research found that White was a prominent Black ballplayer around the turn of the 20th century. Some baseball historians rank him as the best Black ballplayer of the era.

Lester wouldn’t make a fuss over the ranking. He put the ranking this way: “How good did Sol White have to be to play on white teams?”

The answer to Lester’s question: Extraordinarily good.

White was in professional baseball when the only thing black were the shoes the men who played the game wore. He was part of a time in U.S. history when integration ran headlong into racism.

Like other Black men and women, King Solomon White knew racism well. Born in Bellaire, Ohio, after the Civil War, he got into professional baseball in 1887 with the Pittsburgh Keystones of the League of Colored Baseball Clubs.

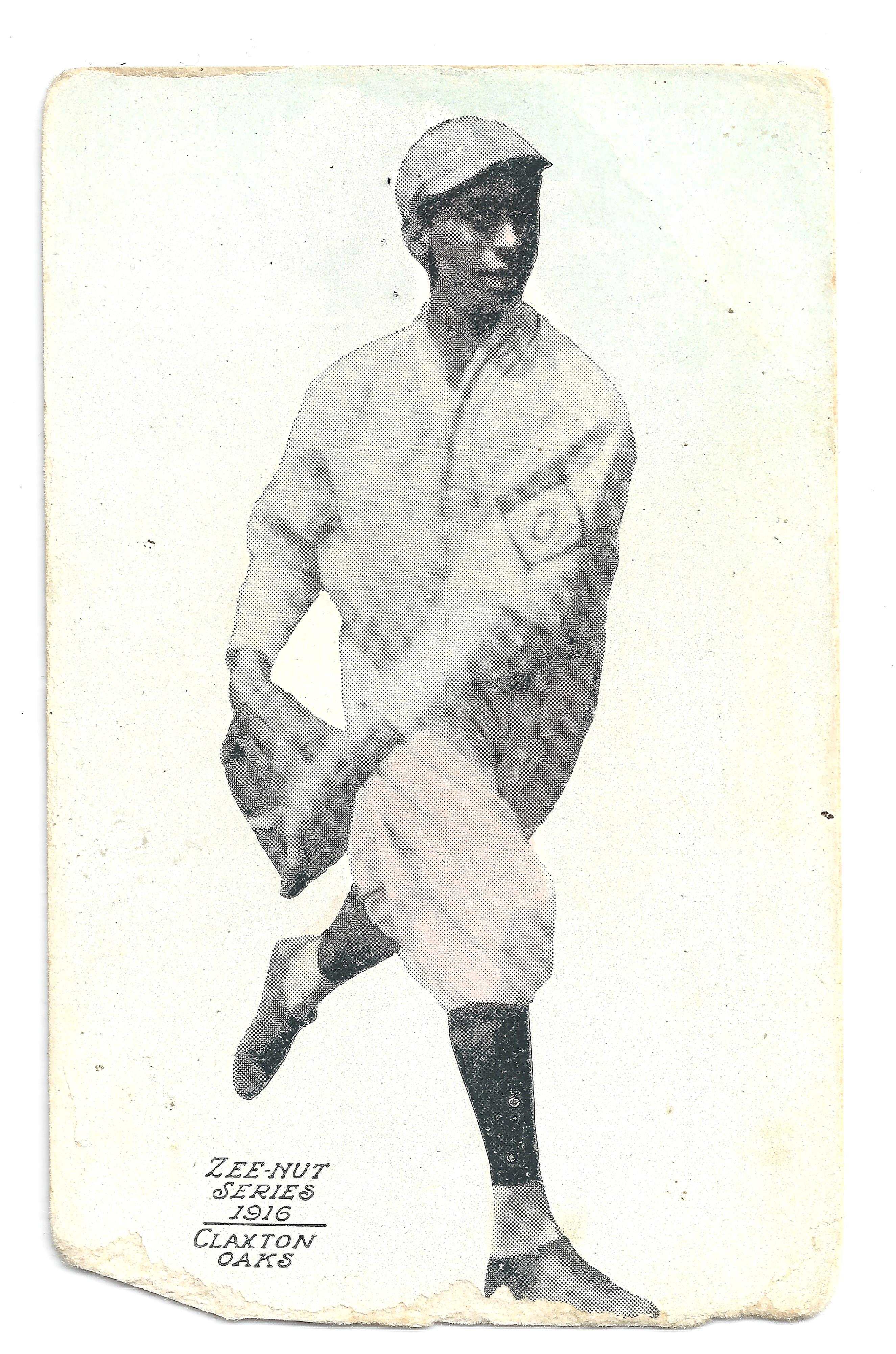

White, a good-hitting, good-fielding second baseman, joined Bud Fowler, Welday Walker and his more famous brother Moses Fleetwood Walker as a few of the earliest Black men to suit up on white teams.

Yet people who study or research baseball will find not much about how well White, Fowler or the Walker brothers played. The record of box scores from the period is incomplete, particularly from the various colored leagues, and stats were not packaged as neatly as they are nowadays.

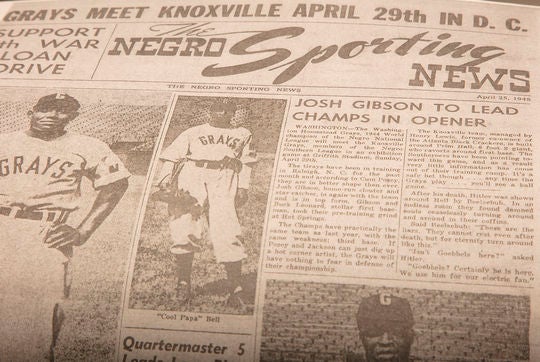

Most games in Black leagues went uncovered in much of the white media, so what was learned of Black players who tried to carve out a living in pro baseball might well fall into the realm of Grimms’ Fairy Tales.

Thank goodness for Sol White. No man contributed more to chronicling those early tales. In 1907, he published what Lester called the “seminal work” on Black players in baseball before the 1910s.

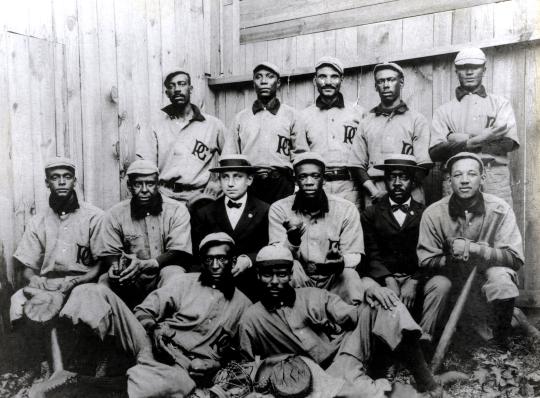

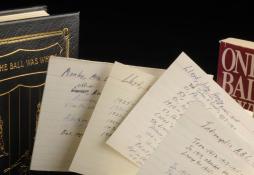

White filled the 128 pages of his “History of Colored Base Ball” with photographs, ads and illustrations, and his work has become an indispensable tool to baseball historians. Few other books exist that spotlight the careers of Black men who played before the turn of the 20th century.

“Realizing the great progress made, and the interest displayed by the players and the public in general, I have endeavored to follow the mutations of colored base ball, as accurately as possible …,” he wrote in the preface.

If not for White’s book, a generation of men who looked like him would have been even more obscure. He flushed out their stories with details not found in any other reference works or newspapers.

“In order to understand the pioneers, the people who came before the Robinsons of the world, you’ve got to start with Sol White’s story,” Heaphy said.

“Colored Base Ball” and its quarter century of history put to bed the notion that Black men didn’t take the sport seriously, Lester said.

White wrote about baseball as a legitimate vocation, one in which color should never matter. He described the game as decidedly masculine, demanding all the manly qualities and powers to the extreme.

Almost as if he had heard the soliloquy James Earl Jones gave in the movie Field of Dreams nearly a century later, White argued that baseball was immune to the attacks of critics. He ought to claim authorship to these words Jones spoke: “The only constant through all the years … has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It has been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt and erased again. But baseball has marked the time.”

Field of Dreams is a different bit of baseball history, and it never attempted to shine a spotlight on Black men who played baseball. White took that role on himself.

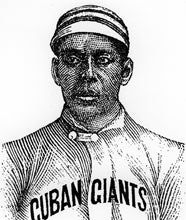

Intelligent and insightful, White sketched an outline of the struggles colored teams had in making a profit. Many were vagabond organizations, hopscotching from city to city to showcase their “stick work.” Yet for all they endured, for all the obstacles in front of these ballclubs, these teams would not die.

The show had to go on.

“From a scientific standpoint, it outclasses all other American games,” White wrote.

It certainly did so on the financial side.

In 1906, a year before he published “Colored Base Ball,” White counted 150 men in colored baseball, and they had an average salary of $466, a few dollars above the average salary of $438 for Americans in all occupations.

White’s research found that the 300 ballplayers in the major leagues had an average salary of $2,000, and ballplayers in the minors made $571.

Regardless of what the salaries in the period were, they came with a cautionary tale for Black ballplayers: Fans came to see flawless performances. The “funny man” in colored baseball was disappearing, he said.

The image of “Black baseball” as a minstrel show had always been hyperbole. Players in the colored leagues had to play with vigilance, activity and quickness or they risked the wrath of fans.

They didn’t have to go to stadiums to see the circus, because Ringling Brothers came to towns near and far too often and satisfied people who liked clowns, lions and acrobats for entertainment.

White made clear that he and his brethren could play baseball with anybody of any color. Their Black leagues, however, didn’t offer the financial foundation to build great wealth, nor could their players avoid the unsettling issues that came with traveling.

Segregation had a tight hold on America, and Black ballplayers felt its squeeze.

“The colored ball player suffers great inconvenience, at times, while traveling,” White wrote. “All hotels are generally filled from cellar to the garret when they strike town.”

The access to lodging made travels from town to town an ordeal, and efforts to earn a living with their white peers came to a halt because of the insistence of Cap Anson, a manager and the brightest star in 1880s baseball, that Blacks could not take the field with or against white ballplayers.

White wrote about Anson and how he used his platform to segregate the game even as some ballclubs wanted to sign the best ballplayers of whatever color.

Anson, though, seemed to have his hands on the pulse of America, circa 1890s. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in its 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision that segregation was legal, Anson had the raw paint he needed to draw a color line.

The white media didn’t quarrel with Anson; few wrote commentary about the wrong of barring Black men from the majors. The Black press spoke sporadically on the topic.

Some people who follow baseball closely say Anson gets too much blame for the color line. Lester is not one of them.

“Unfortunately, the white media gave Anson an excuse — he was a product of his time,” Lester said. “White media tended to sugarcoat his personality — him and other legendary figures.”

In his book, White didn’t dwell on Anson or on those who supported segregation. His prose recounted the tales of Black ballplayers and highlighted the stars in their leagues. White’s writing told of greats from those leagues.

As historians today comb newspaper archives in search of more information about early ballplayers of color, White has provided a starting point. He underlined their names in ink for all to read.

What would people know of pitcher George Stovey, slugger Home Run Johnson, pitcher Kid Carter or second baseman Frank Grant, another 2006 inductee into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, if not for their mention in “Colored Base Ball”?

“That’s why the book is required reading for any serious scholar,” Lester said.

Yet Lester doesn’t know what White, who spent several decades writing for the Black press after leaving baseball and lived to see the AL and NL integrated, thought about Robinson’s breakthrough.

Neither does Heaphy.

No articles have been uncovered in which White addressed Robinson or the erasure of the color line, she said.

“A lot of our appreciation of Sol White is from today’s perspective, from our looking back and recognizing how important he is for us to understanding the game,” Heaphy said. “It doesn’t necessarily mean he was viewed the same way in his day.”

Justice B. Hill, a former senior writer with MLB.com, practiced sports journalism for more than 25 years before settling into a teaching gig at Ohio University. He quit May 15, 2019, to write and globetrot. He continues to do both.