- Home

- Our Stories

- Jimmy Claxton blazed trails via baseball cards

Jimmy Claxton blazed trails via baseball cards

Who was the first Black player to be featured on an American baseball card? In thinking about the answer to that question, it may be tempting to some to say Jackie Robinson, who broke the professional game’s color barrier in the 20th century. Or we could go further back in time and suggest one of the early stars from the Negro Leagues, such as Oscar Charleston, Buck Leonard or Josh Gibson.

Those would all be solid, educated guesses, but they would all miss the mark. The first Black player to appear on an American card is likely a name unfamiliar to most fans of the game, even the diehards who study and appreciate baseball history. He was a player who never played in the American League or the National League, but did later play in the Negro Leagues. He would appear on a card as a minor league player despite the fact that his tenure in the Pacific Coast League lasted all of two games.

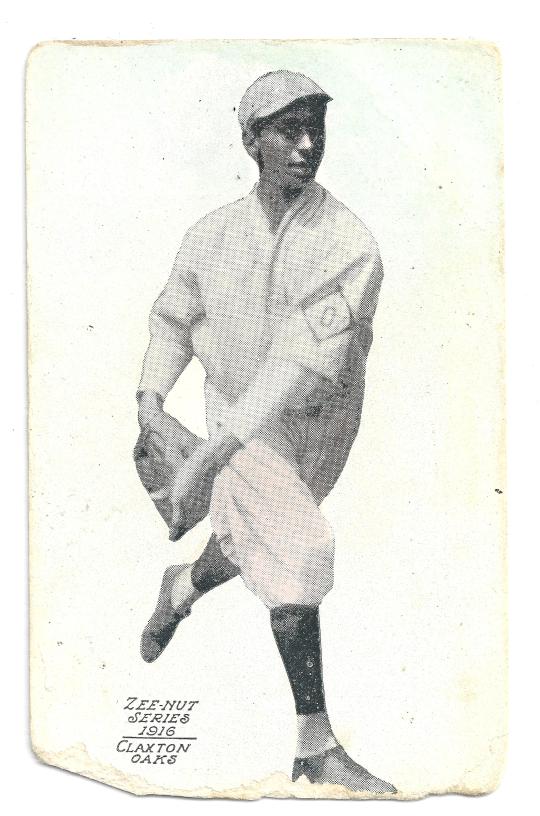

The player? It was a pitcher named Jimmy Claxton. Though Black players appeared on Cuban baseball cards as early as 1909, Claxton became part of history when his 1916 card appeared.

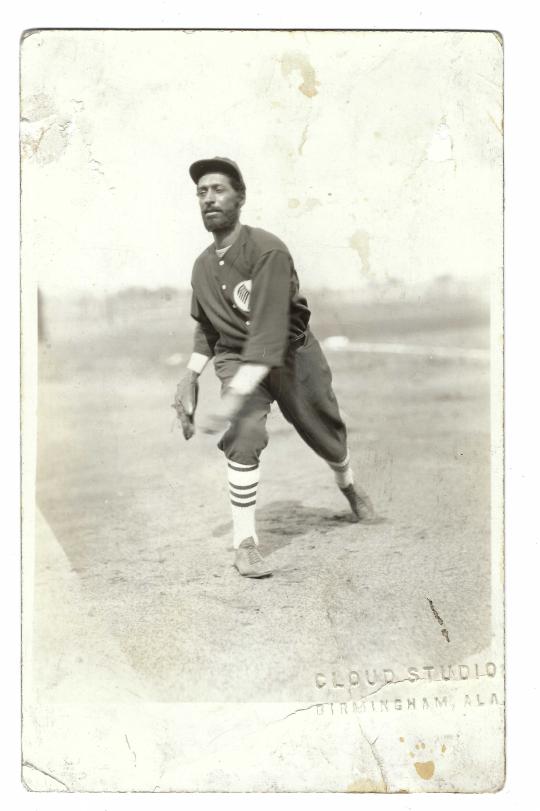

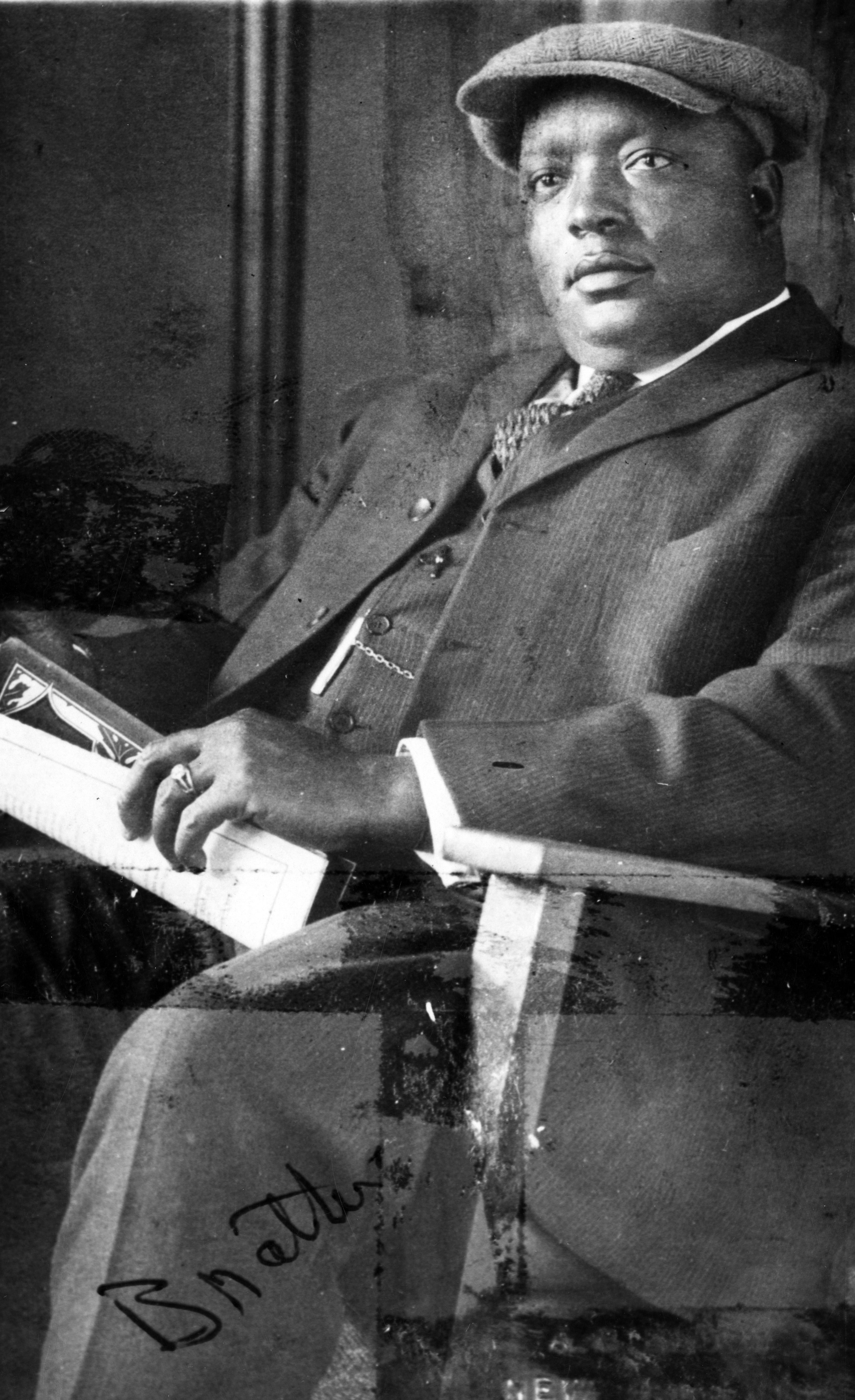

Who was Jimmy Claxton? Born in a mining town in the Canadian province of British Columbia in 1892, Claxton came from a background that consisted of multiple races and nationalities: Black, Native American, English, Irish and French. According to his biography at the Society for American Baseball Research web site: “Claxton described his ethnic heritage as being Negro, French and Indian on his father’s side, and Irish and English on his mother’s.” Census-takers classified him under a variety of categories. When Claxton registered for the draft during World War I, his official registration card listed him as “Ethiopian.”

While most professional ballplayers begin to play the game at very young ages, sometimes as early as five or six years old, Claxton’s interest in baseball came much later. He did not start to play baseball until the age of 13, by which time his family had moved to the United States. Claxton joined a town team in Roslyn, Wash., where he started out as a left-handed throwing catcher. His strong arm led to a position switch, with Claxton moving to the pitcher's mound. That’s where his true talent emerged. Growing into his mid-to-late teens, he became a dominant pitcher for local teams; at his peak, he once struck out 18 players in a nine-inning game.

As talented as Claxton was, there were few opportunities for him to play professionally, given the color barrier that enveloped the American and National Leagues, along with their teams' minor league affiliates. The Negro Leagues, as established by Rube Foster, would not begin play until 1920. So Claxton settled for playing time with independent barnstorming teams. In 1916, he joined an all-Black team in the Oakland area. While pitching for that squad, he drew the interest of the Oakland Oaks, one of the more successful franchises in the Pacific Coast League. A friend of Claxton arranged a meeting between him and the owner of the Oaks, introducing the 23-year-old left-hander as a Native American player, as Claxton’s background did include Native American ancestry. This classification was also strategic as Native American players were not excluded from professional baseball, thereby allowing the Oaks to consider making Claxton a member of their team.

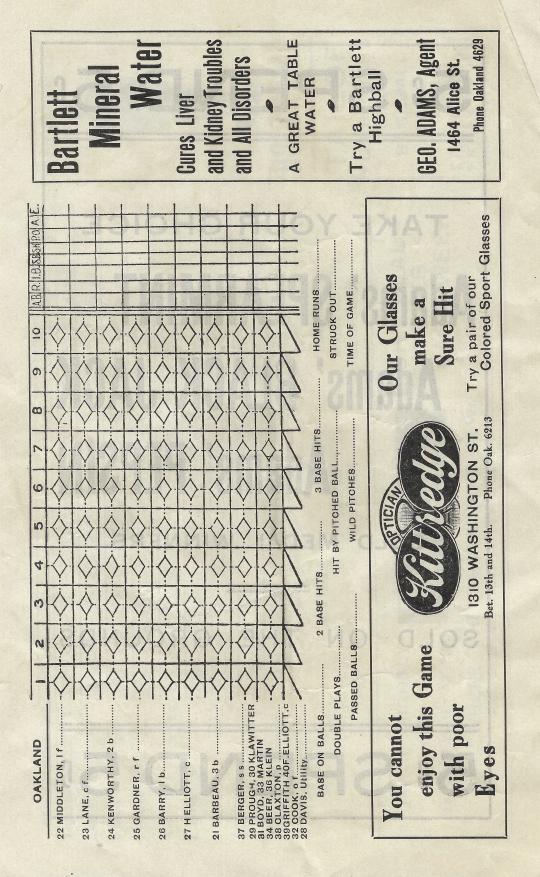

According to Oaks manager Harold “Rowdy” Elliott, Claxton produced an affidavit signed by a notary proving that he was from a reservation in North Dakota, and he was signed by the Oaks to a contract. As a result, it is believed that Claxton became the first Black to play for a professional minor league team in the 20th century. Playing a doubleheader one day, he started the opener and came on in relief in the second game, but did not pitch well. In just two-and-a-third innings, he allowed two earned runs on four hits and three walks. In an article that appeared on May 29, the San Francisco Call offered up an unkind assessment. “The Redskin had a nice windup and a frightened look on his face,” according to the article, “but not quite enough stuff to bother Los Angeles.”

Such a description was subjective, but clearly, Claxton’s performance was not the kind of minor league debut that he, or the Oaks, had wanted to see. Only a few days later, a friend of Claxton allegedly revealed to the Oaks organization that the rookie pitcher was not only Native American but also of Black heritage. According to the story, when the Oaks learned of this, they immediately released Claxton. After just two games, his tenure in Oakland had come to an end.

Rowdy Elliott explained that the decision to release Claxton had to do with his poor performance in the doubleheader. According to an article in the San Francisco Chronicle, “the heaver had nothing on the ball and [Elliott] couldn’t afford to bother with him.” Claxton disagreed with that assessment. In a 1964 interview with the Tacoma News-Tribune, Claxton reiterated his belief that his release had come about strictly for racial reasons. He pointed the blame squarely at Elliott. “The manager was against me and did everything to keep from giving me a fair chance.”

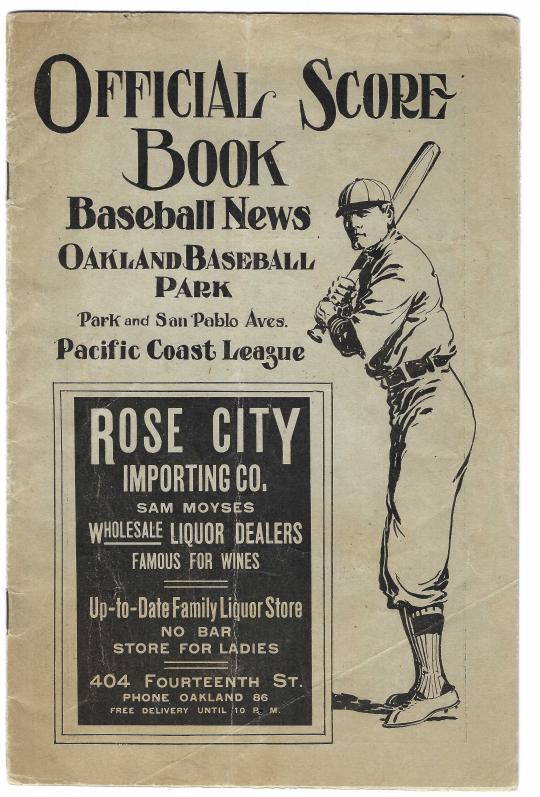

While Claxton’s time with the Oaks was remarkably short, it was long enough for him to be included on a baseball card. The Collins McCarthy Candy Company, one of many candy and food companies producing cards at the time, specialized in producing cards of minor leaguers. Collins McCarthy published sets under the name of Zee-Nut candy bars from 1911 to 1938, creating thousands of cards over that span.

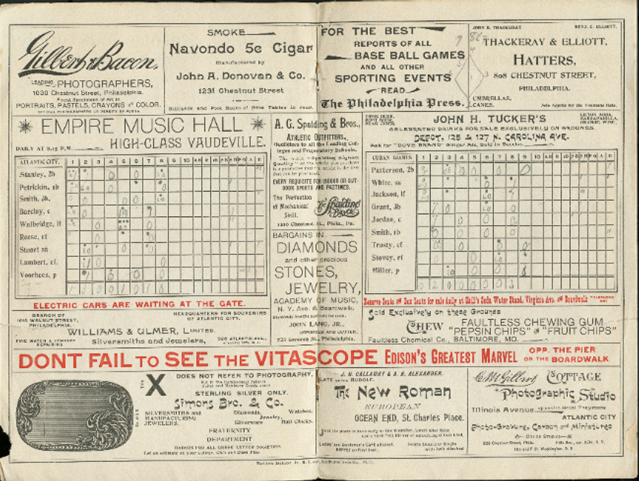

Zee-Nut’s 1916 offerings included a set of cards for the Oakland Oaks, showcasing each player with a black-and-white image. It turns out that Claxton’s week with the Oaks coincided with a visit by the card photographer, a man who worked the Collins McCarthy Candy Company. Claxton became card No. 24 in a set that is known as the “E137 Zeenuts” set. The card features a black-and-white photograph of Claxton in his pitching motion, while set against an all-white background. In very small lettering that is difficult to see at first glance, Claxton’s last name appears in the lower left-hand corner of the card, with the team designation of “Oaks” just below. Some card collectors believe that the Claxton card is the most valuable of all the Zee-Nut cards.

With Claxton jettisoned after his two-game cameo, he would never appear on another baseball card. The next card featuring a Black player would not come out for another three decades, coinciding with the 1947 arrival of Jackie Robinson in Brooklyn.

After his sudden dismissal by the Oaks, a frustrated Claxton might have been tempted to give up the game, but he continued to pursue other opportunities available to him. He joined an all-Black, semi-professional team in California called Shasta Limited (which was likely owned by a railroad company bearing that name). In his best outing for Shasta, Claxton struck out 19 batters, surpassing his high in amateur ball.

Claxton, who died in 1970 at the age of 77, would make a number of stops with various Black barnstorming teams, eventually finding a place in the Negro Leagues. The left-hander joined a team in the East-West League known as Pollock’s Cuban Stars, formerly known as the Cuban House of David. (One of Claxton’s teammates with the Stars was Luis Tiant, Sr., a fellow left-hander and father to the future major league star. Luis Tiant, Jr.) Claxton then pitched for the Washington Pilots, also part of the East-West League. He continued to barnstorm for many semi-pro teams into his early fifties.

Claxton carved out a long career in baseball, but besides the 1916 card, no other baseball cards depicted him, either in or out of a uniform.

If not for that card, Claxton might be completely forgotten. But for collectors of vintage, high-end cards, the Claxton has become highly desired, a holy grail of sorts. Only nine of the cards exist in graded condition, making it a rarity. And perhaps that’s only fitting for this obscure pioneer of Black baseball.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum