- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Black Baseball in Atlantic City

#GoingDeep: Black Baseball in Atlantic City

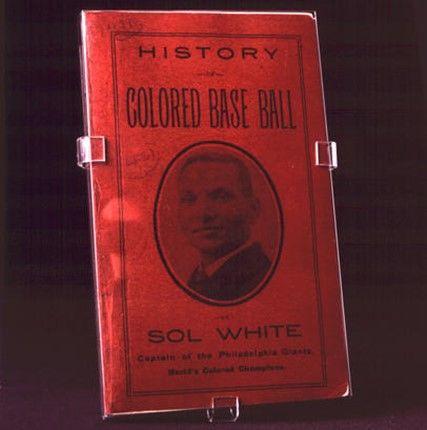

“Barring Chicago or New York,” Hall of Famer Sol White mused in a 1919 column, “Atlantic City is the best town in the country for Colored baseball playing.”

According to White, neither Philadelphia, Kansas City nor St. Louis provided a better environment for Black baseball than the one found in the New Jersey resort town.

Better known today for its casinos and as the real-life location of the streets from Monopoly, Atlantic City proved to be a haven for baseball – especially professional Black baseball – in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This story of Black baseball in Atlantic City reveals itself through artifacts in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s collection.

According to James E. Brunson in Black Baseball, 1858-1900, Black baseball in Atlantic City dates back at least to the 1880s. A number of teams formed, including the Eclipse Base Ball Club, the Mutual Base Ball Club (known as “the Mutuals”) and the Shelburne Hotel Baseball Club, playing against all-white and fellow Black teams. Newspapers noted the success of the Eclipse and Mutual clubs, with the Eclipse team reported as holding “the championship of Atlantic City” after defeating a white team, and the Mutuals dubbed “the champion colored club of America”.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

The Shelburne Hotel team, as their name suggests, was affiliated with the Shelburne Hotel, an Atlantic City resort that opened in 1869. The team belonged to a “Hotel Base Ball League,” comprised of teams from five hotels in the city. These teams contributed to what Brunson calls “colored baseball’s hotel waiter subculture.” Due to a need to provide adequate entertainment for (primarily white) guests, Black waiters and hotel staff needed to “possess additional skills and talents,” and out of this subculture grew some of the earliest professional Black baseball teams.

Perhaps the most famous of those early teams was the Cuban Giants, which began play in 1885. The Giants were based out of the Argyle Hotel, in Babylon, N.Y., on Long Island. They were ballplayers first and foremost but supplemented their incomes with jobs at the Argyle. When their baseball-first priorities eventually conflicted with their hotel duties, they took their chances with the National Pastime, quit the Argyle and began to travel to match up against other teams of their caliber.

The Cuban Giants ventured throughout the East Coast and as far as Cuba for games. Despite what their name suggests, the team was not associated with the country nor were any players from the island. For a time, they made Trenton, N.J. their home base, traveling primarily through New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and Connecticut for games. They played against both white and Black teams, scheduling matchups with local amateur and semipro clubs as well as minor and major league professional teams. Throughout their history, the Cuban Giants made frequent visits to Atlantic City, where there were plenty of hotels and paying guests interested in baseball.

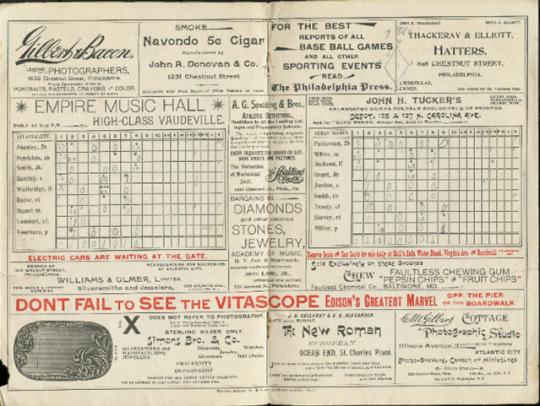

A scorecard preserved in the Hall of Fame’s collection details one such visit to Atlantic City. On July 23, 1896, the Cuban Giants came to town to face the Atlantic City Base Ball Club. The Atlantic City team was made up of white collegiate standouts and played the 1896 season in a circuit known as the Seashore League, which included teams from fellow New Jersey resort towns Cape May and Asbury Park as well as a squad from Newport, R.I.

The July 23 bout was a thrilling game, eventually won 6-4 by the Atlantic City collegians. The Philadelphia Inquirer described the matchup as “exciting throughout, and not till the last man was out was the result of the game a certainty,” while the Press of Atlantic City dubbed the contest “the best yet seen” in Atlantic City. An estimated three thousand spectators attended the game, held at Inlet Park, a baseball stadium located in the Gardner’s Basin area of town.

While the Cuban Giants did not officially belong to the Seashore League, they played frequently against its member clubs, especially Atlantic City. The Cuban Giants (or “Cubes” as the press nicknamed them) made visits to Atlantic City at least as early as 1894, and often played multiple games a year at the shore. In 1896, they scheduled ten games against the Atlantic City squad, and in 1902 the teams met 20 times.

The frequency of visits to the shore suggests both a level of respect between the Cuban Giants and the Atlantic City team and the knowledge that games would draw large crowds and therefore a significant payday. Reports suggest attendance of at least a thousand and as high as five thousand when the Cuban Giants were in town. Their frequent visits also appear to have generated a considerable following among Black residents of Atlantic City.

According to the 1900 U.S. Census, Atlantic City had a population of 27,838 year-round residents, 6,513 (23 percent) of whom were Black. The city represented the only dense Black settlement in the area, as 94 percent of the 6,920 Black residents in all of Atlantic County resided there. In the summer, during peak tourism season, some 200,000 to 300,000 people, both Black and white, filled the seaside town. According to author Nelson Johnson, Black tourists most often visited on specifically-marketed “Colored excursion days,” arriving via train from Washington D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York City.

The tourism industry of Atlantic City provided its Black residents opportunities for stable employment, which was hard to come by elsewhere. Since its inception as a resort town, Atlantic City provided jobs, beginning with the laying of railroad tracks and construction of hotels and houses. Once the town became a full-fledged destination, Black workers operated and repaired amusement park rides, cleaned and maintained hotels and boarding houses, and served as waiters in restaurants. It is no surprise that many Black baseball teams played in town, and that visiting teams like the Cuban Giants drew such large crowds.

At the dawn of the 20th century, Black baseball put itself on the world stage and chose Atlantic City as the location to do so.

A “Colored Championship of the World” was held in 1903, when the Philadelphia Giants faced off against the Cuban X-Giants. The next year, a rematch was held at Inlet Park in Atlantic City. The series, which went the full three games, was well attended, with “hundreds of people coming down from Philadelphia and other points to see the struggle,” reported the Philadelphia Inquirer.

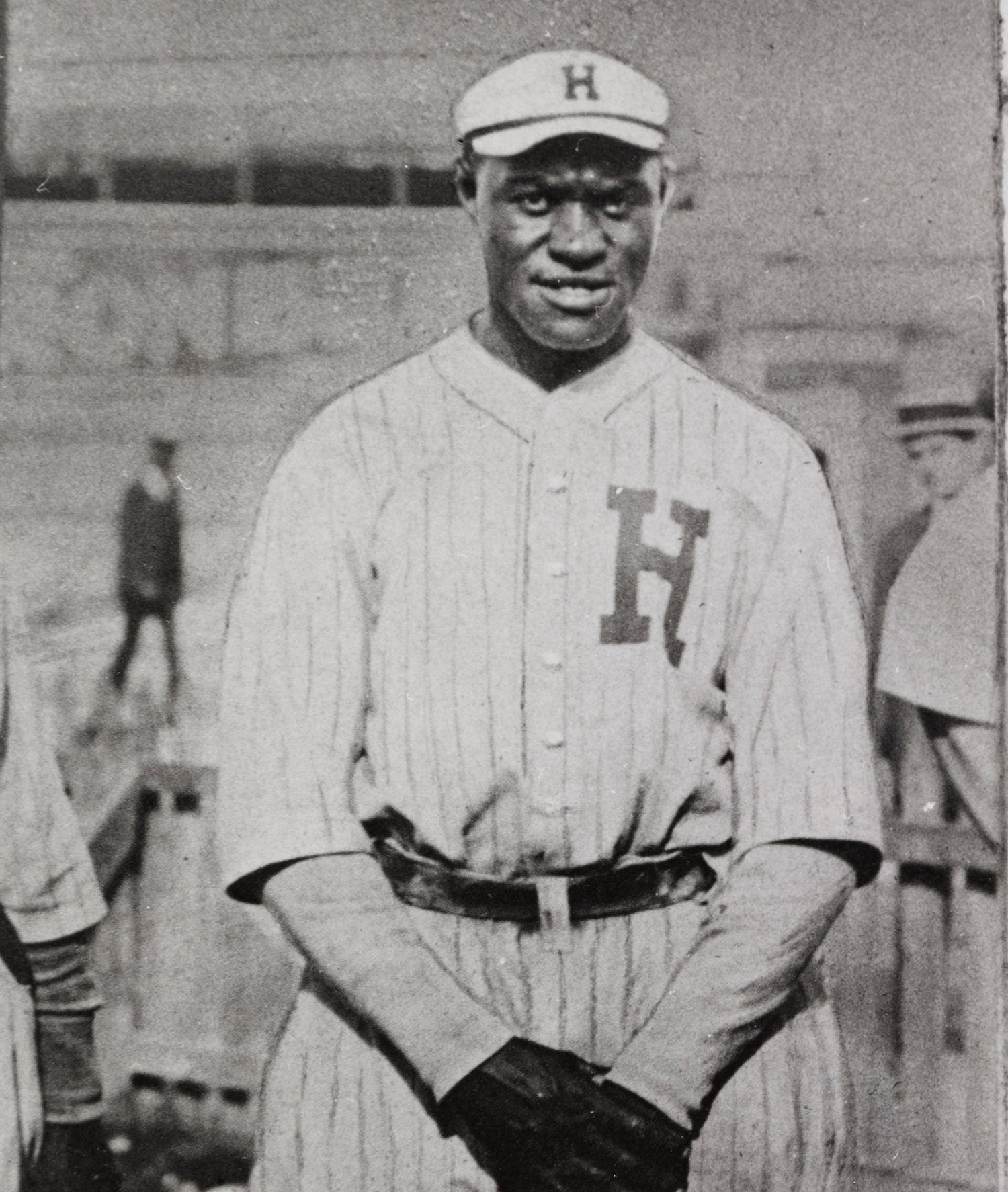

Future Hall of Famer Rube Foster of the Philadelphia Giants emerged as the star of the show, striking out 18 batters in the first game of the series and throwing a two-hitter in the deciding third game. Elected to the Hall of Fame as an executive and known for his role in creating the Negro National League in 1920, Foster was also an excellent pitcher in his playing days.

The 1904 Series was such a rousing success that organizers repeatedly hosted “championship” tournaments at the shore each year until 1911.

The 1905 series followed a similar format, with the Philadelphia Giants facing off against the Brooklyn Royal Giants in a three-game set. A year later the Cuban X-Giants once more played the Philadelphia Giants. A number of Hall of Famers played for these teams, including Foster, Sol White, Pete Hill and Pop Lloyd.

Beginning in 1907, the championship expanded from two teams to four and adopted a round-robin format, with each team playing a number of games against the others and a champion determined based on record. The first such series featured the Philadelphia Giants, Brooklyn Royal Giants, Cuban Stars and the Cuban Giants. The series was met with much excitement and drew large crowds, with an estimated attendance of over five thousand for one matchup between the Royal Giants and Cuban Stars. This format was followed through 1911.

According to historian Brian E. Alnutt, many of the aforementioned “excursion days” which brought Black visitors to the shore occurred in the month of September, coinciding with the championship games. While no game accounts have recorded the demographics of the crowds at Inlet Park, one can infer that Black fans from Atlantic City as well as the home towns of each of the competing teams and across the East Coast were in attendance. Black professional teams, especially the Cuban Giants and X-Giants, always received a warm welcome from the local fans in Atlantic City. The Press of Atlantic City in September 1908 told of a reception held in honor of the Cuban Giants and Philadelphia Giants when they were in town for a championship series.

Other exciting games in Atlantic City during this period included frequent visits from white major league teams, which traveled to the shore from Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Chicago and St. Louis. While the major league clubs typically faced off against local white teams, in 1905 the Brooklyn National League team, then known as the Superbas, split a two-game series against the Cuban X-Giants at the shore.

Black baseball continued on a local level in Atlantic City after the championship heyday of the early 1900s. In 1915, a six-team “Atlantic City Colored League” was formed. While legitimate baseball interest likely played a factor, the Atlantic City Daily Press suggested an ulterior motive, stating that an objective of the league was to keep Black people “off the Boardwalk during the afternoon by providing ball games for them.” The league, like so many Black baseball leagues, provided an opportunity for Black players and fans while simultaneously highlighting the abhorrent reality of segregation. In Atlantic City, where Black residents were barred from enjoying the leisure activities they worked to provide, the hypocrisy of segregationist policies was stark.

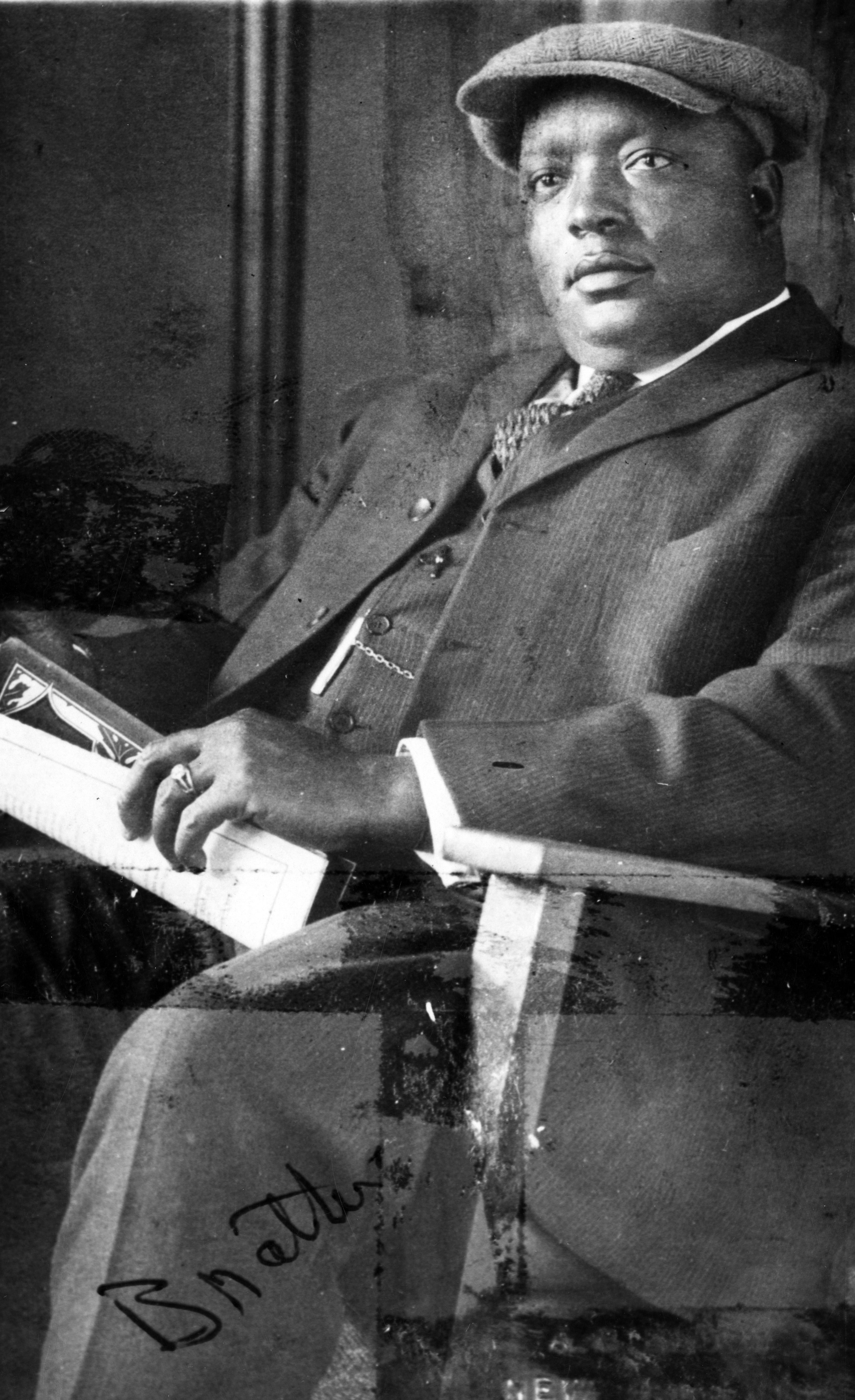

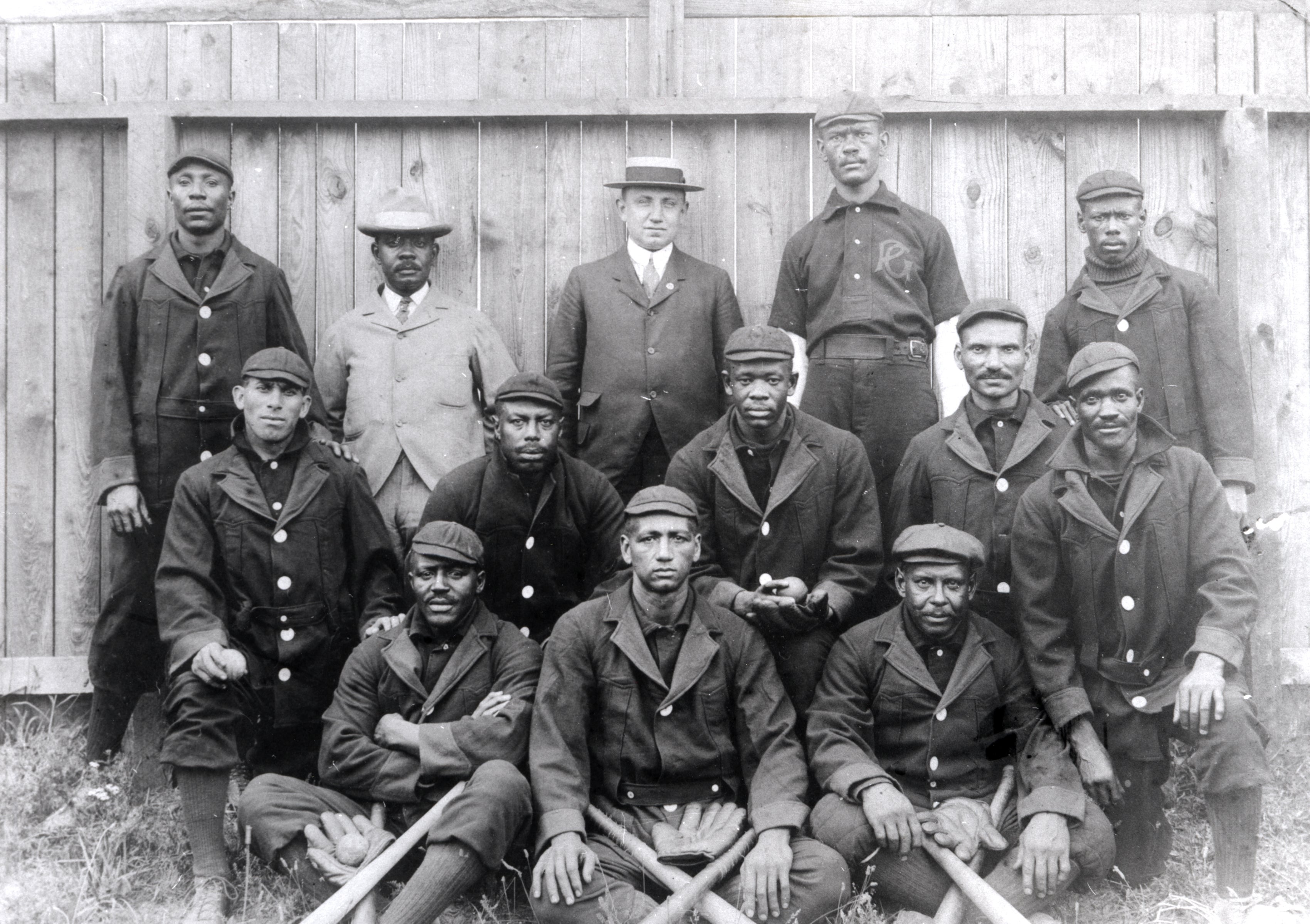

In 1916, Henry Tucker and Thomas Jackson, associates of a white Atlantic City politician named Harry Bacharach, devised a strategy to drum up some support amongst voters. Tucker and Jackson traveled to Jacksonville to recruit a team of Black professional ballplayers, move them to Atlantic City and have them play under the name of the “Bacharach Giants”. The plan worked – Bacharach was elected mayor, and the Bacharach Giants played great baseball and drew lots of fans to the ballpark. The Giants were in fact so good that they directly caused the demise of the Atlantic City Colored League, as they regularly beat the league’s other five teams handily. The Bacharach Giants, known locally as the “Bees” or occasionally “the Mayors,” spent the next several years barnstorming, like many of the early Black teams that played in Atlantic City.

On Feb. 13, 1920, a group of Black baseball team owners, led by Rube Foster, the star of the 1904 championship in Atlantic City, agreed to create the Negro National League. The league featured eight primarily Midwestern teams as full members and two associate members from the East Coast, the Hilldale Club and the Bacharach Giants. The Giants continued as associate members, playing against league teams but not competing for the championship until 1922.

In 1923, the Bacharach Giants and the Hilldale Club joined with the Baltimore Black Sox, the Brooklyn Royal Giants, the Cuban Stars and the New York Lincoln Giants to form the Eastern Colored League, placing them in competition with the Negro National League. Beginning in 1924, the regular season champions from each league met for a championship series, called the “Colored World Series.” The champion was decided in a best-of-nine format, with games played at each team’s home field, as well as at neutral sites in major cities. It was through the success of the Bacharach Giants that a championship series returned to Atlantic City.

The Bees won the Eastern Colored League pennant in both 1926 and 1927, twice facing the Chicago American Giants in the World Series. The 1926 series proved to be epic. It went to the full nine-game extent and then some, as two ties pushed the series to 11 total games. The first two games were held in Atlantic City, before three neutral site games, one in Baltimore and two in Philadelphia. Game 6 saw a return to Atlantic City before the series headed west for five final games in Chicago.

Game 1 ended in a 3-3 tie, called for darkness. Chicago took the first decision of the series in Game 2, a 7-6 victory. Game 3 saw one of the great postseason performances in baseball history. Thirty years before Don Larsen threw a perfect game in the 1956 World Series, Claude “Red” Grier of the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants threw a no-hitter in the 1926 Colored World Series. Grier struck out eight batters while the Bacharach Giants jumped on American Giants pitching, winning by a score of 10-0. Game 4 ended in the series second tie, 4-4. The Bacharach Giants won Games 5 and 6, with Grier picking up his second win along the way, to take a 3-1 Series lead before the teams travelled west.

The American Giants won the first game in Chicago behind the pitching performance of future Hall of Famer Bill Foster. The Bacharach Giants responded, winning a pitcher’s duel in the eighth game as Arthur “Rats” Henderson tossed a complete game shutout. The Atlantic City nine was one win away from a World Championship, ahead in the series 4-2. The wheels then fell off for the Bees as Chicago took Game 9, 6-3, and then won Game 10 in a 13-0 blowout.

Knotted up at four games apiece, the World Series headed for a decisive 11th game on Oct. 14. Another pitcher’s duel, the final contest remained scoreless headed into the ninth inning. The Bacharach Giants had chances to score throughout the game, mustering 10 hits and three walks, but excellent defense and clutch pitching by Bill Foster kept them off the scoreboard. In the bottom of the ninth inning, American Giants center fielder Jelly Gardner singled, advanced on a bunt and came around to score on a hit by left fielder Sandy Thompson to win the game, and the championship, for Chicago.

In the 1927 postseason, the same teams met and drew the same result. Chicago won the first four games, on their home field, before the series shifted east. Atlantic City won Game 5, tied Game 6, and won Games 7 and 8 to close the gap. Chicago prevailed, however, in an 11-4 blowout in Game 9, to win their second consecutive World Series.

The end of the 1927 season marked a turning point both for Black baseball and for the Bacharach Giants. The 1927 series was the last World Series held in the Negro Leagues until 1942. The Eastern Colored League disbanded partway through the 1928 season, and the Negro National League followed suit in 1931. The Bacharach Giants continued play independently in 1928 and in the short-lived American Negro League in 1929 but struggled with low attendance and financial difficulties. The team disbanded in early 1930, ending Atlantic City’s run as a home to Major League Baseball.

Throughout their tenure in Atlantic City, the Bacharach Giants featured many great players, including Pop Lloyd, Rats Henderson, Dick Lundy, Luther Farrell and Oliver Marcell. Some former players, most notably Lloyd, chose to make Atlantic City their home after retiring from baseball.

Lloyd became a beloved figure in town and helped keep the spirit and history of Black baseball alive there. He worked as a janitor at the post office and then in the public schools. Lloyd also played a little baseball, serving as a player-manager of an amateur team named the Johnson Stars, later called the Farley Stars, both named after local politicians, as the Bacharach Giants had been. It was during his days with the Stars that Lloyd first met and managed Max Manning, who would go on to pitch in the Negro Leagues for the Newark Eagles and win the 1946 Negro League World Series.

In 1949, as a testament for the love and respect the town had for Pop Lloyd, a baseball stadium was built and named for the aging baseball star. The stadium, which occasionally hosted Negro League games in the 1950s, remains extant in Atlantic City, providing a space for local kids to play baseball and serving as a reminder of the town’s rich baseball history.

Statue of John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, who played for and managed the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants. After his playing career, Lloyd spent the remainder of his life in Atlantic City, where a stadium was named in his honor in 1949. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Manning, who returned to his native Pleasantville, N.J., as a schoolteacher after his playing days, served as an ambassador for Black baseball history in the area until his death in 2003. Manning became the president of the Pop Lloyd Committee, a group established to honor the memory of Lloyd and Black baseball. The committee, under Manning’s leadership, first organized to raise funds for the restoration of Pop Lloyd Stadium and later shifted their focus to provide educational programming and create a humanitarian award named for Lloyd, as well as a scholarship in honor of Manning. He also served as vice president of the Negro League Baseball Players Association.

The efforts of Max Manning and others did not go unnoticed, and Atlantic City’s connection to Black baseball has not been forgotten.

In 1998, professional baseball returned to Atlantic City after nearly seven decades. The Atlantic City Surf were an independent league team playing first in the Atlantic League and later the Can-Am League.

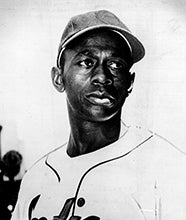

The Surf played at a ballpark aptly named “The Sandcastle,” which featured a picturesque outfield view of the casinos making up the Atlantic City skyline. Through commemorative elements at the ballpark as well as special theme nights, the Surf made an effort to promote the history of Black baseball at the shore. A bronze bas-relief sculpture titled “Out From the Shadows” was unveiled at the ballpark in 1999, created by artist Jennifer Frudakis. The sculpture depicts notable people and themes relating to Black baseball, including the likenesses of Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Rube Foster, Pop Lloyd and Max Manning, as well as images representing barnstorming and segregation. Lining the walls of the ballpark’s entrance is a mural depicting notable figures in baseball history, including Manning.

The Surf hosted a number of “Turn Back the Clock” events, in which players wore Negro Leagues-inspired uniforms and former Negro Leagues players were invited to the stadium. Unfortunately, while the events were intended to honor the former players and their careers, at times they invoked the hypocritical policies of the past. One year, the former Negro League players, invited to the game as honored guests, were booted from a luxury box in favor of paying customers. The disrespect reminded the former players of the segregation they faced in their playing days. Belinda Manning, Max’s daughter, told the Press of Atlantic City that this gave “an ugly new meaning” to Turn Back the Clock Night, and the players ended up boycotting the game. After eleven seasons and one league championship, the Atlantic City Surf ceased operations in 2009.

While professional baseball has not returned to Atlantic City since, the connection to the game lives on. Through the work of Manning and the Pop Lloyd Committee, and at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, the story of how a summer resort town transformed into a hub for Black baseball is told.

David Lewis was the 2022 curatorial intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development