- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: The Forgotten History of Numbering Players

#GoingDeep: The Forgotten History of Numbering Players

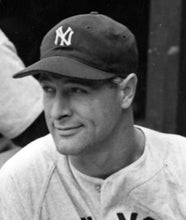

On Jan. 6, 1940, Yankees President Ed Barrow announced that Lou Gehrig’s No. 4, the only uniform number he had ever worn, would never again be used by a member of the club. The offseason declaration marked the first time in baseball history that a player’s uniform number had been retired. And yet, when the 19-year-old first baseman made his big league debut with the club in 1923, nearly six years before the Yankees first donned uniforms with numerals on their backs, he was assigned the No. 27, not 4.

How is that possible? The answer lies in a long-forgotten chapter in the history of numbering baseball players.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Forty-five years before Barrow made his historic proclamation, an unnamed individual suggested to James Hart, president of the National League Chicago White Stockings (now known as the Cubs), that his baseball players don uniform numbers. Hart endorsed the idea, which was detailed in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of Dec. 29, 1894:

Every one who has attended a ball game knows how puzzled one occasionally gets in endeavoring to recognize some player or trying to locate a man who is on the team, but whose position has been changed from that signified on the score-card. The plan suggested to Mr. Hart is very simple. It is for every man on the team to have a separate number, which he shall keep throughout the season. … On the score-cards, the names of the players, with their numbers, shall be printed; and in this way the spectator can readily identify any player on the field.

The proposed scheme was not new in the realm of sports. In horse racing, the practice of placing numbers on jockey silks began in the mid-1850s, if not earlier. Calls to have American football players don numbers started in the early 1880s. By the time of the baseball proposal, pinned numerals adorned the sleeves or backs of polo players and bicycle racers. But for baseball, talk was cheap and the National Pastime resisted the fan-friendly innovation.

In late 1906, a dozen years after Hart’s numbering plan, Charles Murphy, the new owner of the Cubs, revived the idea. This time, however, the suggestion gained a foothold, though not initially in Chicago and not by physically placing numbers on uniforms. Instead, cost-conscious team magnates concocted a new scheme that, not surprisingly, aided profits.

Eliminating the time and money required to add numerals to the sleeves or backs of jerseys, the new plan entailed printing a unique number next to each player’s name in the scorecards sold at the park and displaying these numbers in lineups posted on new-fangled electric scoreboards. This meant that to decode the numbering system, fans had to purchase a scorecard. And to top things off, wily owners would at times change these numbering assignments so that fans could not rely on the codes remaining the same each time they went to the ballpark, thus requiring them to buy new scorecards at every game they attended.

Newspaper reports from 1907 suggest that various American League clubs had already erected or planned to install new scoreboards that could handle this innovative numbering system. This included a new scoreboard at Boston’s Huntington Grounds, then the home of the Red Sox, that quickly garnered a modicum of criticism. The Altoona Tribune of May 25, 1907, griped that “Boston’s electric score board is a frost. When the balls and strike [sic] sign is working properly the batter sign on the other end makes a few changes not on the programme.” Just a few weeks later , longtime baseball writer Sy Sanborn of the Chicago Tribune grumbled that “the electric score board installed at the Huntington avenue grounds is a distinct failure.”

Despite initial hiccups, the scoreboard/scorecard numbering scheme flourished. By 1911, electronic scoreboards using the coding system were found at big league parks such as Boston’s South End Grounds, Cleveland’s League Park, Detroit’s Bennett Park, Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, Washington’s National Park, and both of Chicago’s big league fields: West Side Grounds and White Sox Park.

Most of these scoreboards were likely manufactured by the World Score Board and Advertising Company, a Chicago-based firm that had acquired the patents of a local electrician George Baird in 1909 or 1910. Baird’s patent papers described how the devise featured various plates that:

… bear numerals. This is especially advantageous in the case of batters. The numerals may readily be made of a sufficiently large size to be distinguished readily from all the distant portions of a base-ball ground, whereas names upon the plates could not be read except from close at hand. The numbers employed will correspond with those assigned to the players in a printed or other list of the players supplied for the guidance of the audience, as for instance upon the usual score-cards or score-sheets which are employed for keeping record of the game.

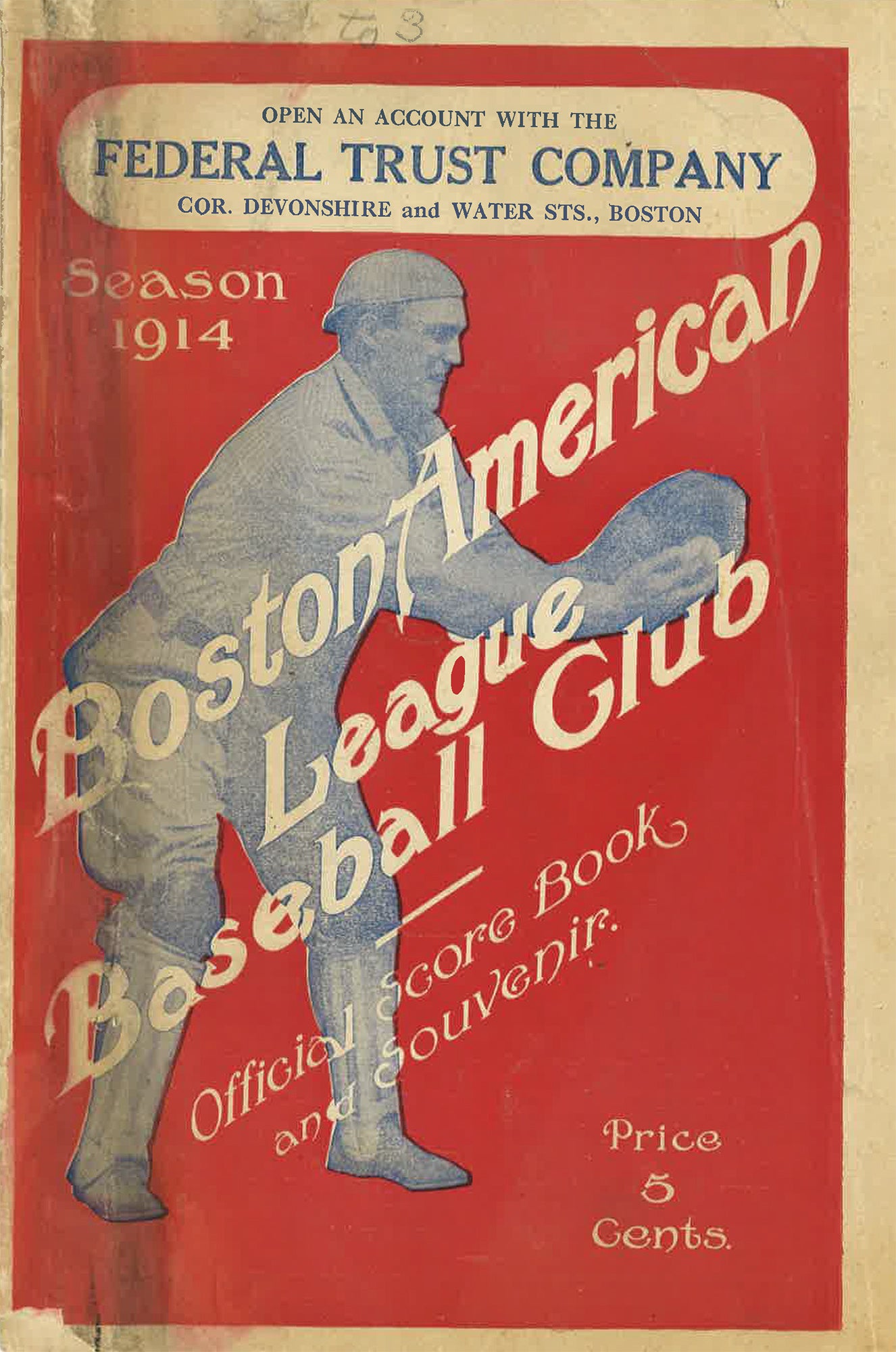

This early method of numbering players can be found in old scorecards that feature printed numbers next to player names, as well as explanations as to how fans could make the connection between the players, the numbers and the scoreboard. The Hall of Fame’s archives includes numerous such scorecards.

Red Sox scorecards from Fenway Park’s inaugural 1912 season included this simple explanation of the system: “Follow the electric Score Board for changes—Every player has a Number as indicated.”

Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, this method of numbering players and selling scorecards proved successful, and yet teams still discussed and experimented with the more direct method of affixing numerals to uniforms. Baseball clubs such as the Cuban Stars in 1909, the Cleveland Indians in 1916, and the St. Louis Cardinals in 1923 dabbled in donning numbered jerseys, but it was not until 1929 that the practice of placing numerals on the backs of team shirts truly took hold. That season the Indians and Yankees introduced the now-familiar tradition and within a few years every major league club followed. Scorecards and scoreboards were still equipped to assist fans in identifying players by numbers, but now the players’ uniforms also helped out.

Today, the fan – in the stands, watching on television, or streaming on their smart phone – has numerous ways to keep track of who’s who on the diamond. Scoreboards, scorecards and digital devices use not just player numbers, but player names, images, video and audio. But few recall that just a decade into the 20th century, when ballpark vendors cried “You can’t tell the players without a scorecard,” they really meant it.

Tom Shieber is the senior curator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; the research for this article was done in close collaboration with Cassidy Lent, Library Director at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum