- Home

- Our Stories

- Scorecard from Babe Ruth’s debut preserved at Museum

Scorecard from Babe Ruth’s debut preserved at Museum

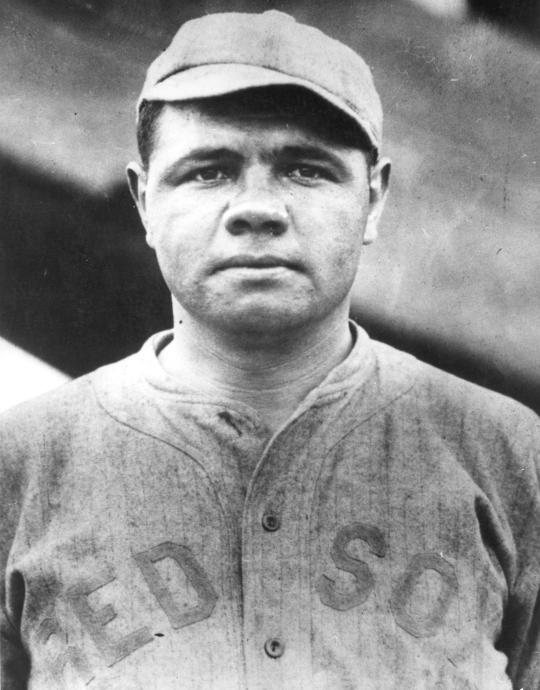

Babe Ruth was an unknown teenager when he took the mound for his big league debut in 1914.

Thanks to some inspired research, a program/scorecard from that afternoon’s historic moment has recently been discovered in the collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

On Saturday, July 11, 1914, the Cleveland Naps visited Boston’s Fenway Park – in only its third season as the home ballpark to the Red Sox – to start a four-game series.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

With temperatures in the mid-70s and light winds, the announced crowd of 11,087 was excited for not only the perfect baseball weather but also its first chance to see their newly acquired southpaw.

Ruth, along with fellow pitcher Ernie Shore and catcher Ben Egan, were sold by the International League’s Baltimore Orioles to the Red Sox on July 9, 1914. The trio boarded a train in Baltimore on July 10 and rode all night – 400 miles in total – to Back Bay Station in Boston, arriving at 10 a.m. Later that first day they went to Fenway Park and reported to manager Bill Carrigan.

“Though this is his first year in professional baseball, those who claim to know a player when they see one have stamped Ruth as a second Rube Waddell,” proclaimed The Boston Globe on July 10, 1914. “Ruth is a strapping big fellow and has just rounded out his 20th year. He has an inexhaustible supply of stamina, can wield a bat like an outfielder, and as a pinch hitter was one of the best the Baltimore fans ever saw. His chief stock in trade is speed, but he also has a sharp-breaking curve and a tantalizing slow ball.”

On account of the condition of his pitching staff – Smoky Joe Wood and Rube Foster being injured – Carrigan announced to Ruth that he would be starting against the Naps that day.

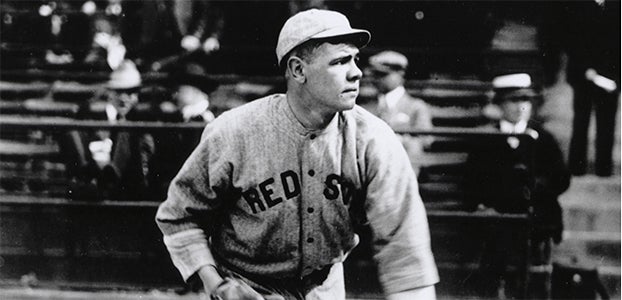

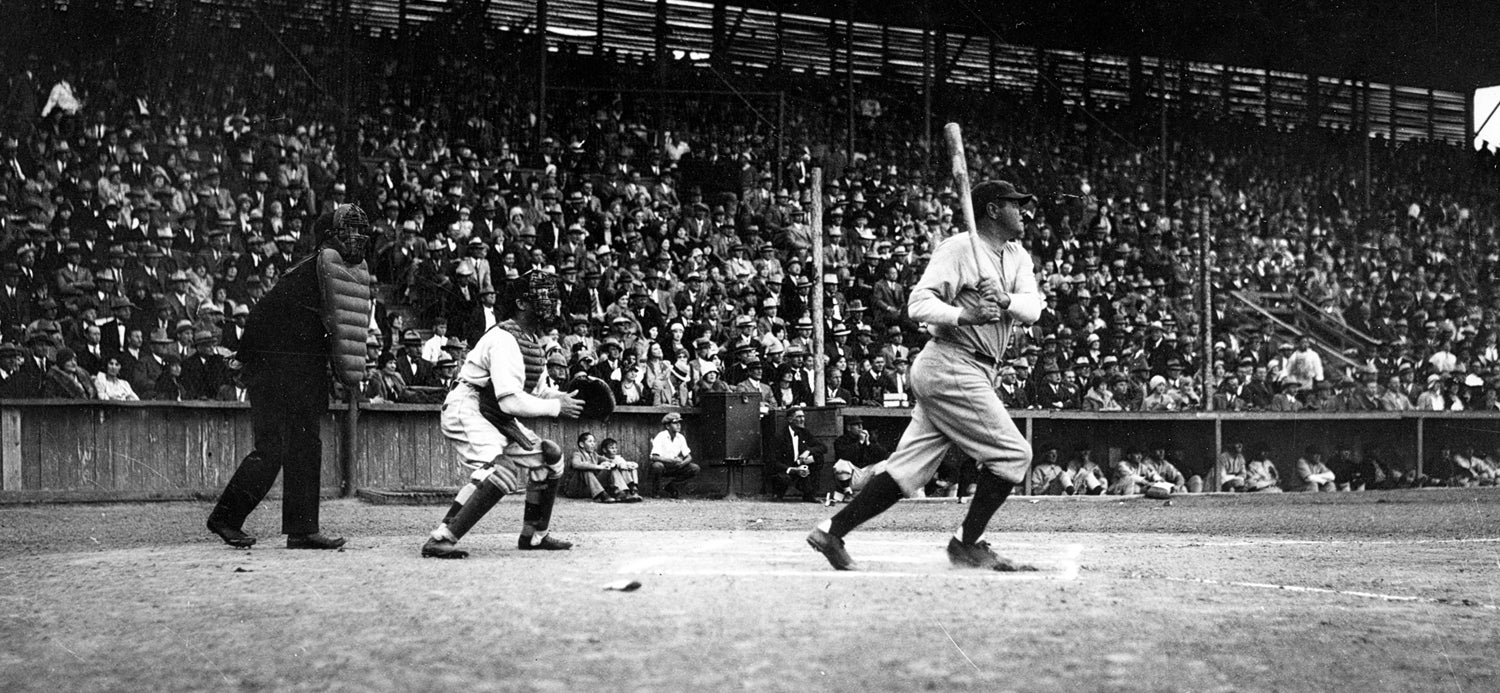

Ruth, only 19 years old, confidently strode to the mound for the 3 p.m. game. He showed none of the weariness one would expect from a player who arrived in Boston that morning after an all-night train trip. Though nobody knew it at the time, this would be the start of the big league story for one of the greatest athletes the country has ever known.

The renowned slugger was, in his formative years, one of the great left-handed pitchers of his era and proved successful in his first game. Ruth picked up the victory in the 4-3 Boston win, tossing seven innings while giving up eight hits, two walks and two earned runs while striking out one and giving up no bases on balls in the 93-minute game.

While Shoeless Joe Jackson collected two singles off Ruth as did Jack Graney – the 2022 Ford C. Frick Award honoree – future Hall of Famer Nap Lajoie was 0-for-4. The future Sultan of Swat went hitless in two at-bats before being pinch-hit for in the seventh inning.

The next day’s newspapers featured headlines praising the newcomer: “Ruth leads Red Sox to victory,” “Southpaw displays high class in game against Cleveland,” “Ruth debuts well” and “‘Baby’ Ruth works.”

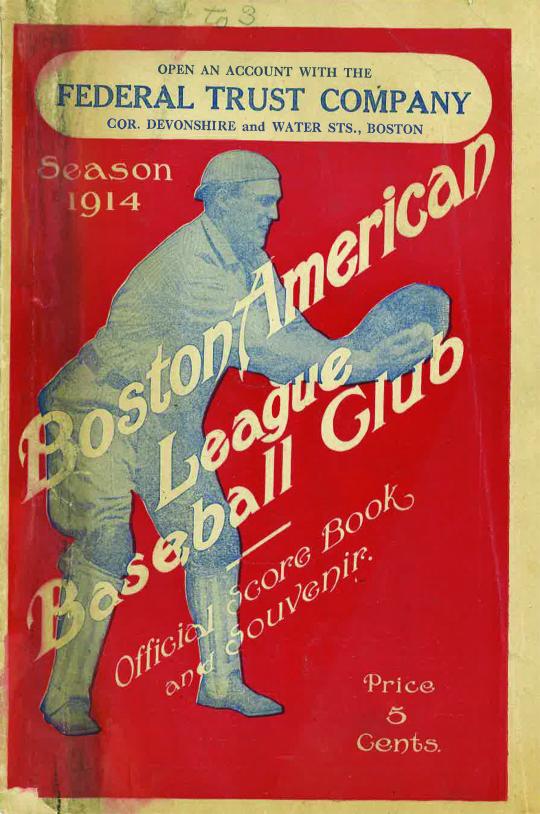

Fast forward to 2022 and Hall of Fame’s senior curator, Tom Shieber, was doing research on scorecards and was curious if the Hall of Fame had early ones for Fenway Park. His interest was piqued when he found one clearly marked on its cover from 1914. But he needed to do further research to lockdown its exact date.

“At first, I wasn’t particularly hopeful about that, because the best way to figure out the exact date is if the scorecard is completely filled out,” Shieber explained. “Essentially the line scores are close to unique if not unique.”

One major component to unraveling the mystery to this was the handwriting on the scorecard portion of the program itself. While it isn’t scored, per se, it does have written in pencil the number “4” on the Boston side and the number “3” on the Cleveland side. It was the only Naps versus Red Sox game played at Fenway Park all season with a 4-3 score. While not conclusive, it was a major clue.

The program/scorecard was donated with minimal information as part of a larger collection of items to the Hall of Fame in 2000. At that time, the donor referenced this particular item as a “1914 Red Sox program from a game against Cleveland” and in a separate listing as a “1914 Red Sox program, undated for game vs. Cleveland.”

The 20-page program/scorecard, measuring 6 inches by 9 inches, features on its cover a catcher receiving a ball. It also reads “Season 1914,” “Boston American League Baseball Club,” “Official Score Book and Souvenir” and “Price 5 Cents.” Inside are more than 60 advertisements, ranging from Carl A. Weitz’s Genuine German Frankforts and the Oliver Typewriter Co. to Dixon’s “Anglo Saxon” Pencils and the Fenway Garage.

Ultimately, Shieber, through more in-depth research, was able to determine that the scorecard was in fact from Ruth’s debut game by eliminating dates via the printed rosters and lineups listed inside.

In particular, the fact that Guy Cooper is listed as a member of the Red Sox means the scorecard was printed after May 27, the date the Yankees sold him to Boston, while Fritz Coumbe and Rankin Johnson being listed as members of the Red Sox means the scorecard was printed before July 28, the date Boston sold the pair to Cleveland for Vean Gregg.

Despite the fact that there were still obvious questions with the program/scorecard, with Ruth not listed anywhere and the printed Red Sox lineup differs from the actual lineup used on July 11, they are explainable.

As a cost savings measure as well as practical reasons, the Red Sox would print up all their program/scorecards for each game of a homestand before the start of each homestand. The homestand in question started July 8, but Ruth was not sold to the team until July 9, while an earlier injury to star outfielder Harry Hooper affected the assumed lineup that day.

“All signs point to this being the from the game that Babe Ruth debuts,” Shieber said. “From a storytelling standpoint, it’s helpful when you can tell a story from page one of chapter one. It’s a great entree to being able to tell the story of Babe Ruth from his very first major league game.

“And it’s pretty difficult to get a bigger name than Babe Ruth. Here’s a guy whose name is still meaningful today. We’re three-quarters of a century after he’s passed away and he’s still a recognized name by eight year olds.”

In fact, 1914 is noteworthy for many reasons in Ruth’s life, as his fortunes changed for the better in an amazing rapid succession of events – going from a reform school to the minors to the majors in a matter of months.

The remarkable turning point in George Herman Ruth’s life came in 1914 when he signed his first professional baseball contract. Before that, though, he was sent to Baltimore’s St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys by his parents at the age of seven because he was considered incorrigible – an event would change the course of his life and prove to be his salvation because it exposed him to baseball.

Word of Ruth’s success on the diamond for St. Mary’s ultimately reached Jack Dunn, the owner of the local Baltimore Orioles of the International League.

Though the hard-charging Orioles were off to a great start in 1914, a Baltimore franchise in the short-lived Federal League soon siphoned off enough fans that Dunn had no choice but to sell off some of his best players.

“The Red Sox introduced Mr. Ruth, one of the Baltimore recruits, yesterday to the crowd at Fenway Park,” wrote Tim Murnane, a 1978 recipient of the BBWAA Career Excellence Award, in the July 12, 1914 edition of the Globe.

“All eyes were turned on Ruth, the fast lefthander, who proved a natural ballplayer and went through his act like a veteran of many wars. He has a natural delivery, fine control and a curveball that bothers the batsmen, but has room for improvement and will, undoubtedly, become a fine pitcher under the care of Manager Carrigan.”

Ruth could hardly believe that he made a big league club in his first year as a professional.

“Only five months since I had been a schoolboy, sliding on a pond in a Baltimore industrial school,” Ruth said. “And the salary was less believable – $2,500 a year.”

Ruth’s whirlwind year of 1914 came to a conclusion with his marriage to the former Helen Woodford, a Boston waitress, on Oct. 17 outside Baltimore.

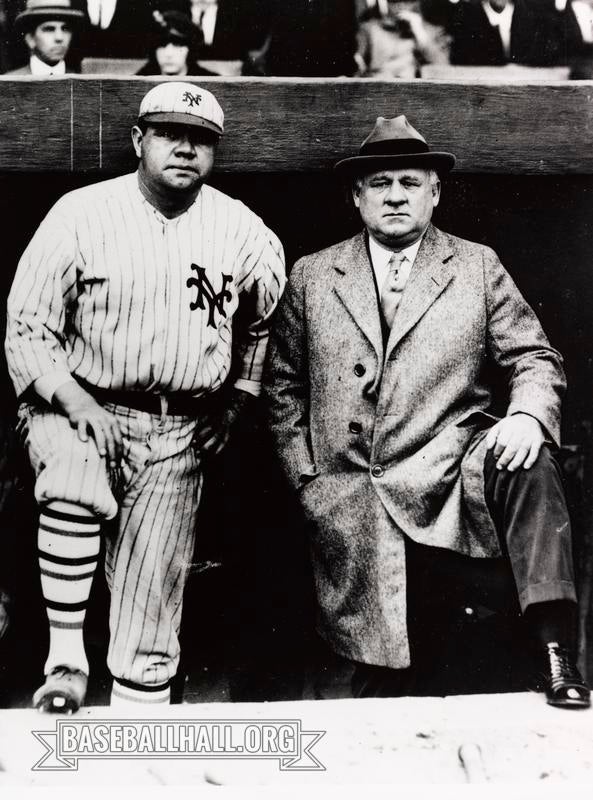

The highs and lows of 1914, both professionally and personally, would be only a prelude to what was to come. Ruth retired in 1935, ending a remarkable 22-year big league career with 714 home runs. The “Sultan of Swat” would ultimately lead the Red Sox to three World Series crowns as a pitcher and the New York Yankees to four Fall Classic titles as a right fielder before becoming one of the five inductees in the Baseball Hall of Fame’s inaugural election in 1936.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum