- Home

- Our Stories

- Negro Leagues became major league with the help of groundbreaking research

Negro Leagues became major league with the help of groundbreaking research

On Dec. 16, 2020, Major League Baseball announced that Negro Leagues Baseball from 1920 to 1948 would henceforth be considered a Major League.

In many ways, the genesis of that proclamation can be traded to a group of authors and researchers who – with the backing of the Hall of Fame and MLB – began putting together the official Negro Leagues record two decades ago.

“Negro Leagues baseball only existed because of the bias of Major League Baseball. They had no choice but to create their own leagues, and they were modeled on Major League Baseball,” said Larry Lester, author of multiple books and articles on the history of Negro Leagues Baseball, and along with Larry Hogan and Dick Clark, served as a coordinator for the Negro Leagues Researchers and Authors (NLRAG) group during the first decade of the current millennium.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

The NLRAG was the group of scholars responsible for a comprehensive study of the history of black baseball, and also produced an exhaustive data base of statistics on Negro Leagues baseball between 1920 and 1948.

They were funded by a grant project sponsored by the National Baseball Hall of Fame with support provided by the Office of the Commissioner of Baseball. When the project was announced in July of 2000, then-Hall of Fame President Dale Petroskey said: “The documentary record of the African-American contribution to our National Pastime is incomplete and this endeavor will go a long way toward filling those gaps. This is an extremely important research project, allowing us to further our mission as an educational institution.”

Hogan, Lester and Clark proceeded to recruit a team of outstanding scholars and researchers, and work commenced immediately. The objectives of the study were twofold. The first was to prepare a comprehensive historical narrative of Black baseball from the mid-19th century through the integration of Major League Baseball. The second goal was to identify and organize all available statistics from the golden era of the Negro Leagues between 1920 and the late 1940s. Hogan would head up the narrative program, while Lester and Clark would tackle the statistics.

After many years of sustained effort, the group would submit a narrative and bibliography which exceeded 900 printed pages. While the full text of this report rests in the Hall of Fame Library, a more popular version was published by National Geographic in 2006. Titled “Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball”, it remains a seminal work on baseball history, and many of the contributors have gone on to publish additional titles further expanding the scope and depth of our knowledge of black baseball.

The remaining element of this study would prove to be a massive undertaking. As there were no official publications of Negro Leagues statistics, one would have to be created from scratch, and it would not be a simple task. First, they would need to determine what should be counted. There was no such thing as Negro League Baseball – a similar to white baseball, there were multiple black leagues, and not all played at the same level. Also, what games should be counted? While each league offered a planned schedule at the beginning of the season, there would be changes due to rain outs and financial situations.

The Negro Leagues teams also played exhibition games throughout the season, many against lesser quality squads, one of many factors to consider.

In the end, it was determined they would count only league-sanctioned games for which a scoresheet, box score, or play-by-play narrative was available. Inter-league contests, along with exhibition games against major league teams would also be counted. This decision gave the group focus, and provided a foundation on which comparisons could be conducted. It meant that meaningful comparisons with Major League Baseball could also be presented.

As one researcher said, “Instead of comparing apples to oranges, we can compare Cortland apples to Gala apples. They may not be exact, but at least they are in the same fruit group.”

Lester and Clark pulled together a team of several dozen qualified researchers and baseball data specialists. They would cull through over 345 newspapers to locate the data on a page-by-page, game-by-game basis. There were hundreds of black-owned newspapers in production around the nation, and these would prove to be a gold mine of data.

Most white-owned newspapers gave very little thought to covering black baseball. The study would rely heavily on the Negro newspapers, an important part of the vibrant African-American community that existed in this era.

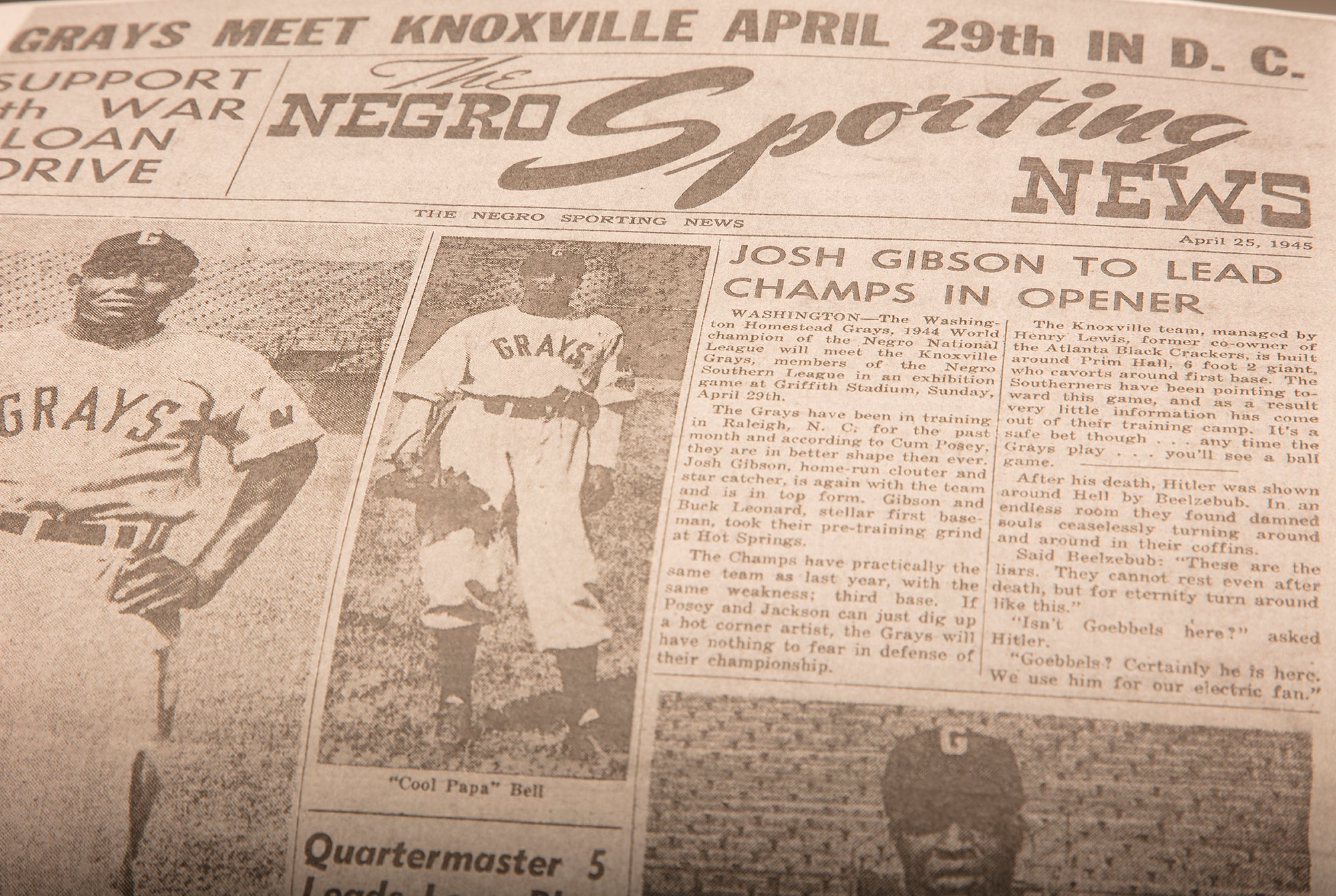

Known as the Bible of Baseball, the Sporting News in particular, did not cover the Negro Leagues with any frequency, what Lester calls an “injustice of omission.” This is despite the fact that they could draw large crowds during games held at major league ballparks. If one reads through the Sporting News during these years it is possible to find detailed coverage of baseball at every level, even Class D, but you would not know there was a collection of highly-talented African-American players toiling about the country, engaged in a game they dearly loved.

As work progressed, the team began to accumulate game data and entered it into a spreadsheet for presentation and analysis, but they had to overcome several other problems. For example, box scores normally list players by last name only, and there are some names very common within black community. The researchers had to dig deep to identify first names so that individuals would be properly credited. RBI and ERA statistics would also prove challenging, requiring cross-referencing multiple box scores with related stories to make final decisions.

The results of the study far exceeded what the Hall of Fame and Major League Baseball had anticipated. The combined hitting and pitching data, when printed, amounted to more than 9,700 pages of day-by-day statistics, and includes information on more than 3,400 players. The database covered the 1920s exhaustively, while there were some missing data from the 1930s due to a reduction of coverage as newspapers struggled during The Great Depression. The 1940s data is exhaustive, but coverage began to dissipate after Jackie Robinson broke the color-barrier in 1947.

Never before had such numbers on the Negro Leagues been organized in this fashion. The NLRAG, Baseball Hall of Fame, and Major League Baseball did not want this material gathering dust on a library shelf, but it was rather expensive to produce a 9,700-page encyclopedia. So the spreadsheet was made available to Baseball-Reference.com, where it was loaded into their website and is available today – for free – to anyone with access to the internet.

According to Lester, “All indications were that the data was solid and comparable to MLB. On a year-to-year basis, there tends to be a variance of no more than five percent between MLB and NLB statistics.”

Not every player was a superstar, the Negro Leagues had their own collection of utility players, cup-of-coffee guys and others who were average ballplayers. Not everyone was of Hall of Fame caliber. But like MLB, those players that were stand out. Since 1971, many have been recognized with induction into the Hall of Fame.

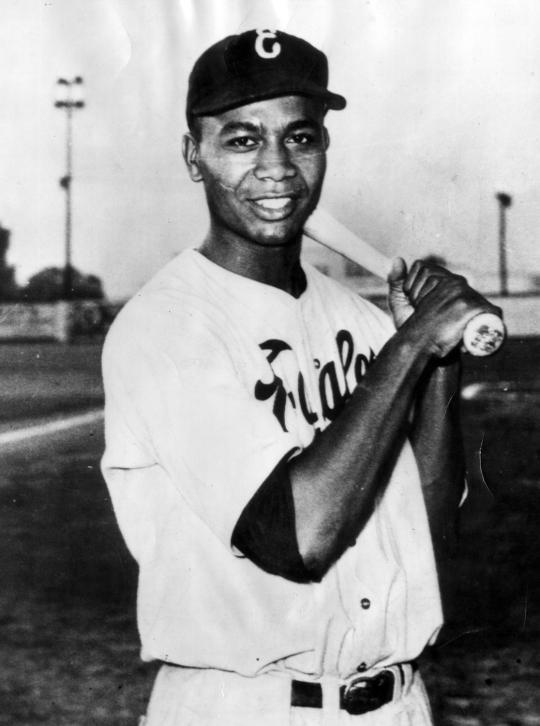

Some myths were also shattered. For example, Josh Gibson is credited with only 113 home runs, but he achieved those in just 1,957 at bats. This is one homer for every 19 at bats, a ratio which places him in the same class with all the great home run hitters in major league history. This comparison proved to be a solid indication of the similar level of play between the Negro Leagues and Major League Baseball.

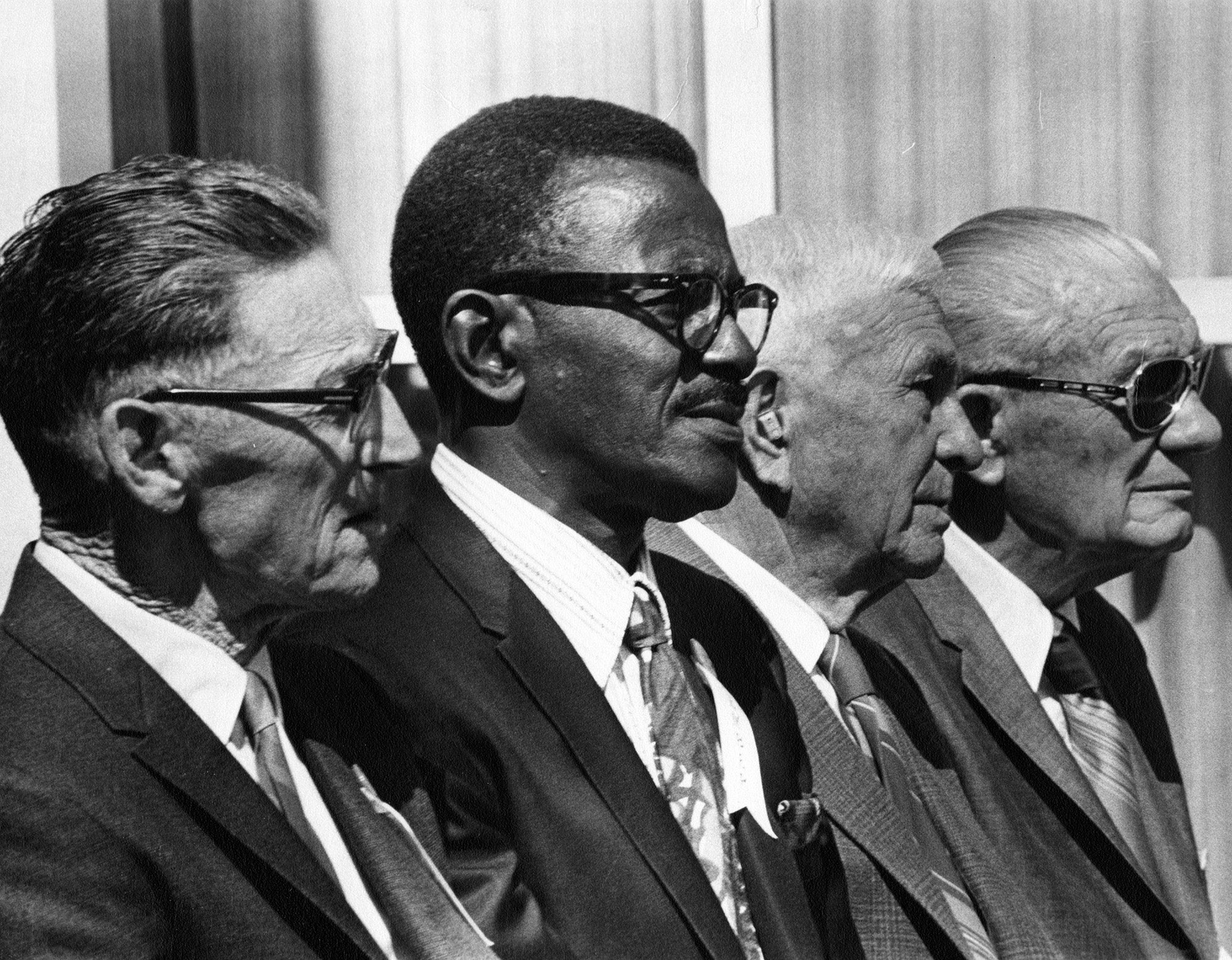

In fact, the study resulted in the creation of a special committee which reviewed the data and elected 17 new Hall of Famers in 2006. This special committee included multiple members of NLRAG, so their work not only resulted in an expansion of baseball scholarship, but also in the addition of new members to the Hall of Fame’s Plaque Gallery. Their efforts have forever added to the pantheon of baseball heroes.

It was not easy, but it was a labor of love for many on the NLRAG team. After the study was completed and the numbers submitted, many of these researchers continued digging, and the data at Baseball-Reference.com continues to be updated. There is also a comparable database at the Seamheads website. While the players from the Negro Leagues are the heroes of this story, the individual researchers involved in this massive and continuing project should also receive their share of the accolades for this wonderful contribution to baseball history.

“All of us who love baseball have long known that the Negro Leagues produced many of our game’s best players, innovations and triumphs against a backdrop of injustice. We are now grateful to count the players of the Negro Leagues where they belong: as Major Leaguers within the official historical record,” said Commissioner of Baseball Rob Manfred.

The announcement mentioned Lester and others, and gives full credit for their combined efforts that help make this decision a reality.

“Negro Leagues players used the same baseballs as Major League Baseball, they ordered their bats from Louisville Slugger, their uniforms came from Wilson, they played at major league ballparks, using the same game rules,” Lester said. “The basic infrastructure of the game was the same. That they were a major league is not debatable. The only difference was the color of their skin.”

James L. Gates is the Librarian Emeritus at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum