- Home

- Our Stories

- Yankee Half Century

Yankee Half Century

As the sun peeked over the treetops of Otsego Lake on Monday, Aug. 12, 1974, a shortstop for the Elmira Pioneers was sleeping on a couch in the lobby of The Otesaga Resort Hotel. His name was Eddie Ford, and he had arrived at the hotel in the middle of the night with the intention of seeing his father, Whitey Ford, inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, alongside Whitey's friend and teammate, Mickey Mantle.

Later that day, Mantle and Ford would be honored along with Negro League legend Cool Papa Bell, the great first baseman Jim Bottomley, 19th-century stalwart Sam Thompson and the umpire’s umpire, Jocko Conlan. But at the crack of dawn on this wonderful day, Eddie was trying to get some shuteye.

“We had a game in Niagara Falls the night before,” Eddie recalled. “As soon as the team bus got to back to Elmira, I hopped in my orange Toyota Corolla and drove for two-and-a-half hours to Cooperstown. Hit a poor rabbit along the way. But when I got to The Otesaga around 2 a.m., the person on duty wouldn’t let me go upstairs to my parents’ suite. So I sacked out on a couch in the lobby.

“You know what woke me up? The voice of a woman giving the people at the front desk hell. It was my grandmother, Nana Edith, yelling at them for not allowing me to go upstairs. I later came to discover that while I was trying to catch some sleep, Mickey and his sons and my brother Tommy were downstairs in the game room shooting pool.”

Indeed, they were. “The security guard had kicked us out earlier that night,” Dave Mantle recalled. “But we weren’t going to take no for an answer. When the guard was out of sight, we lifted my younger brother Danny, who was 14 at the time, up and through the transom at the top of the door. When he dropped to the floor on the other side, he unlocked the door.”

Half a century later, it seems only fitting that a few misadventures were mixed into the celebration of the greatness of the two Yankee legends. From 1950 until 1964, the Bronx Bombers appeared in 13 World Series, 10 of them with both Slick and The Mick. And they had a good time doing it, freely partaking of the trappings of success in New York City.

The fact that Eddie Ford had to wait to get into his room was also a poetic reflection of sorts. Whitey had come up a mere 30 votes shy in the 1973 Baseball Writers’ Association of America's Hall of Fame balloting, his first year of eligibility. Mickey’s first year on the BBWAA ballot would be 1974.

“It’s almost as if the voters knew that the two of them should go in together,” said Marty Appel, the Yankees’ public relations director back in ’74. Adding to that notion is this parallel fact – never before, in the 35 years of the Hall of Fame, had two players who played for only one team been elected by the BBWAA in the same year.

The festivities really began on the two buses that Mantle and Ford had chartered to take their friends, relatives and former teammates from Manhattan to Cooperstown. “The buses were parked at the St. Moritz Hotel,” Dave Mantle said. “But we couldn’t leave until people came back from seeing Blazing Saddles, which had just come out. That much I remember. The rest was kind of a blur for an 18-year-old.”

The buses themselves seemed to have come out of Kismet. Whitey and Mickey had first met each other on a team bus that stopped off at Donahue’s in Astoria, Queens, on April 14, 1951, for the wedding reception following Joan and Whitey’s marriage. The Yankees had an exhibition that day at Ebbets Field, so on the way back, their bus stopped off to wish the Fords the best. Joe DiMaggio and a few of the other Yankees disembarked to toast the happy couple.

As Whitey later recalled, “When Joan and I found out that some of the players were still on the bus, too shy to attend the reception, we decided to climb on board to thank them. And that’s how I first met a rookie named Mickey Mantle. Little did we know that 23 years later, we would go into the Hall of Fame together. We’ll always be teammates.”

Those lucky enough to attend the Hall of Fame’s dinner in the main dining room of The Otesaga on the eve of induction day couldn’t help but feel they were in a dream in which the plaques on the wall come to life to drink and dine, swap stories and get their Hall of Fame rings. As Whitey described it in Slick, the autobiography he wrote with Phil Pepe, “Joe DiMaggio was there, and Casey Stengel, Hank Greenberg, Satchel Paige, Charlie Gehringer and Bill Terry. We just sat around telling stories and having dinner, and I had a great time.”

Also there were Warren Spahn, who had been inducted the year before, as well as Rube Marquard, Roy Campanella, Bob Feller, Monte Irvin, Lefty Grove, Harry Hooper, Jesse Haines, George Kelly, Stan Coveleski, Stan Musial, Joe Medwick, Lloyd Waner, Red Ruffing, Eleanor Gehrig and the Commissioner of Baseball, Bowie Kuhn. At the end of the dinner, Terry got up and implored the new Hall of Famers to make the pilgrimage to Cooperstown every year.

“After dinner,” Ford wrote, “I went to my room to work on my speech for the next day. I couldn’t believe it when Mickey told me he wasn’t even going to prepare a speech. ‘You’re crazy, Mick,’ I said. ‘I’m telling you, you’d better write something down or you’re going to be lost for words when you get up there.’ Mickey just waved me off and went to play pool.”

The next morning, having gotten the clearance to go upstairs, Eddie showered and changed into the nice outfit his mother had brought for him. “After breakfast, I sat in one of those rocking chairs on the veranda, looking out at the lake and thinking I was in heaven. What a glorious day.”

It was, as Bob Broeg wrote in the Sporting News, “a morning as bright as the red geraniums that decorated the exterior of the Hall of Fame Library.” From the dais on the porch of the Library, Museum Director Ken Smith conducted a crowd of about 2,500 in the singing of the national anthem. After a few presentations, the microphone was turned over to Commissioner Kuhn for the very reason that the folks had come.

He said: “I will simply read to you the words as they appear on these plaques, because the words tell more than anything I could add of the greatness of these men as baseball players.”

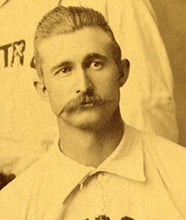

Leading off was Sam Thompson, who hit .415 in 1894 while also topping the NL in home runs twice and RBI three times. Accepting his plaque was his nephew, Lawrence Thompson. The widow of Jim Bottomley was then given the proof of his prowess – six consecutive seasons in which he drove in 100-or-more runs, his single-game record of 12 RBI, his lifetime average of .310.

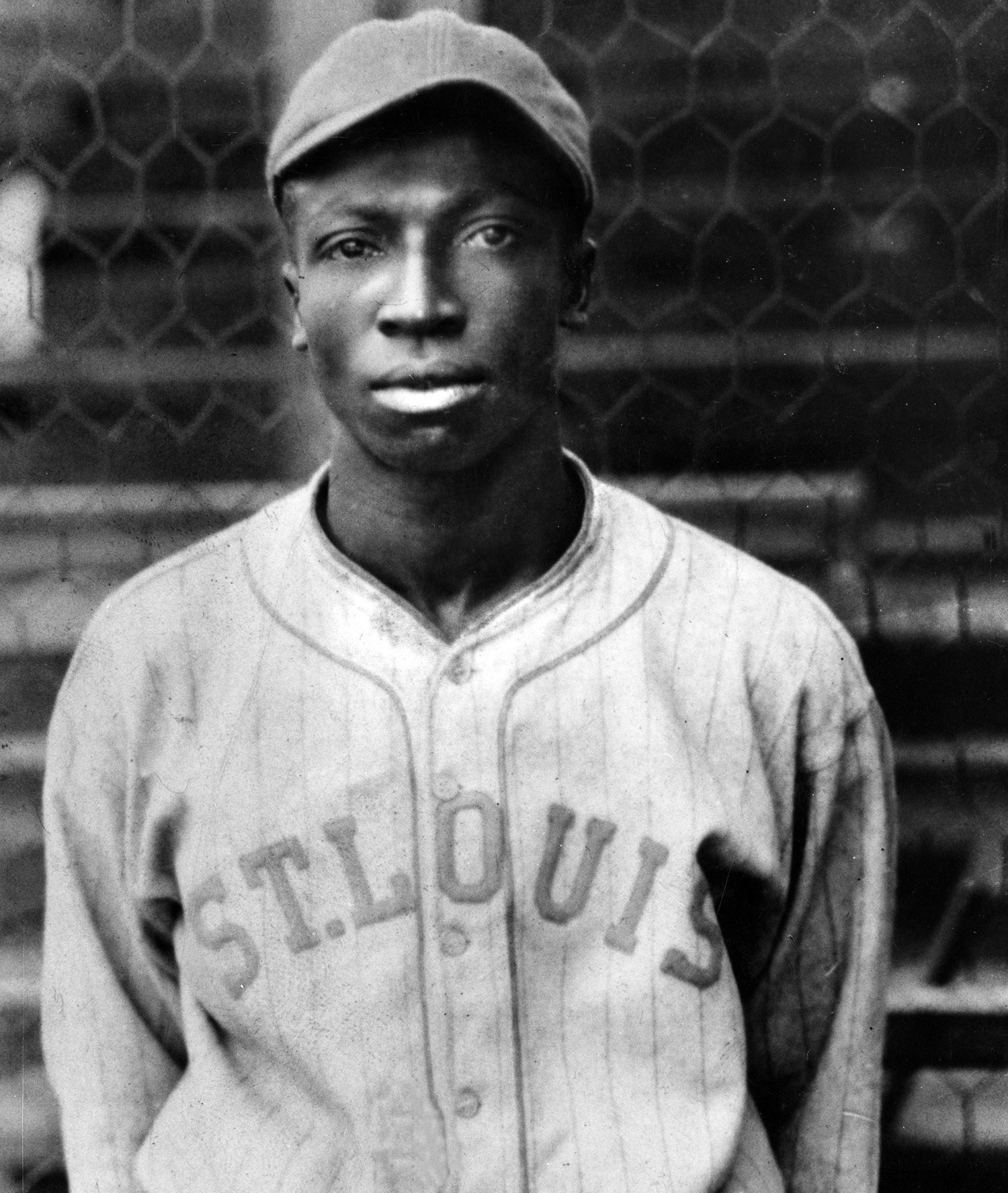

Batting third was Cool Papa Bell, the fifth player from the Negro Leagues honored with a plaque. The fabled speedster for the St. Louis Stars was a fortuitous choice because that summer, another St. Louis outfielder, Lou Brock of the Cardinals, was on his way to stealing a modern record 118 bases. Bell came well-prepared – he had been practicing his autograph in anticipation of the many requests he would receive – and well-dressed in a gold ensemble put together with the help of Cooperstown mayor Harold H. Hollis.

After the Commissioner spoke of his speed, batting skills and longevity, Bell told the crowd, “I thank God for enabling me to smell the rose while I am still living.” He then proceeded to sweetly thank a multitude of relatives, politicians, teammates, opponents, writers like Broeg and even his third-grade teacher. There was just one problem. He forgot to thank his wife of 46 years, Clara Belle, who was in the audience. Cool Papa was so mortified that he later begged Kuhn to thank her for him at the 1975 inductions.

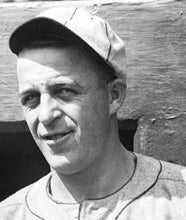

Whitey was up next. He was worried, and not just about his own speech. Jocko Conlan had just whispered to him that he was having pains in his chest. “Oh God, I thought. The man’s going to have a heart attack right here on the stage.” Then he heard Kuhn say, “He posted the best winning percentage among 20th-century pitchers… He was one of the greatest clutch performers in the history of our game. Whitey Ford.”

He came up clutch again. “Thank you, Commissioner. I tell you I walked down the aisle three weeks ago with my daughter, she got married and I thought I was nervous then, but I think this tops that today. Between what happened in Washington last week and up here in Cooperstown today, I have to say it’s a pretty good week for the Fords.” (Gerald Ford had just become President following Richard Nixon’s resignation.)

The man who still signed his autograph “Ed Ford” then talked about his Yankees family – DiMaggio, Yogi Berra, Roger Maris, Stengel and, of course, Mantle.

“Mickey said if I didn’t throw so many long balls to center field, he probably could have played another five years, and I believe it.” Then he recognized his own family – his mother, wife Joan and his three children, pointing out that Eddie was in the Red Sox organization.

As for Conlan, who came next, he turned out to be fine – it was just the heat and the heat of the moment. Even a man who had worked five World Series and six All-Star Games could feel the pressure of baseball immortality, saying, “Never did I ever dream that I would be selected to receive this greatest of honors.”

Whitey needn’t have worried about Mickey, either. He had been saved for last not just for the credentials the Commissioner rattled off – the 536 home runs, his three MVPs, his 20 All-Star Games, his World Series records. As Kuhn said, “He was simply one of the greatest players the games has ever known,” and as Kuhn didn’t need to say, he was one of the most popular players in the history of the game.

Part of that popularity stemmed from his self-effacing charm, and Mantle played to that strength, thanking the Commissioner for leaving out his record 1,710 strikeouts. He also thanked his late father for naming him after another Hall of Famer, Mutt’s favorite player, Mickey Cochrane, and for not using Cochrane’s actual first name, Gordon.

He roamed around a little, as if the speech were center field in Yankee Stadium, introducing his mother and talking about growing up in Commerce, Okla., and how his dad would come home from the mines and play ball with him until dark. He made a little side trip to the time he was going to open a chicken restaurant with a slogan that his wife, Merlyn, told him not to use in the speech, but he was going to tell it anyway: “To get a better piece of chicken, you’d have to be a rooster.” The crowd broke out in laughter, but as David said, “Mother was not happy.”

But then The Mick talked about getting discovered by Yankees scout Tom Greenwade and breaking in with the likes of Berra, DiMaggio, Rizzuto and Ford, whom he called “our real leader, all the time.” As for Stengel, who looked on with tremendous pride at his proteges, Mantle said he was “the man most responsible for me standing right here today.”

After introducing his own family – Merlyn and the four boys – he thanked everybody for coming. “It’s been a great day for all of us and I appreciate it very much.”

When the applause finally died down, Kuhn said, “Ladies and gentlemen, that concludes our 1974 program.”

As it turned out, something else was beginning. One of the many journalists in attendance that day was a rising senior at Syracuse University who was working for WSYR-TV, the NBC affiliate in Syracuse.

“I was a huge Mantle fan,” said Bob Costas, who was 22 at the time. “But I was there to do a piece, and I had no idea of what kind of access I would have. But as luck would have it, I ran into Don Ross, the president of the Syracuse Blazers Eastern Hockey League team – I was doing their games on the radio for $35 a game plus $5 meal money.

“Now Don knew Mickey because when the Yankees came up to Syracuse for their annual exhibition game with the Chiefs, Don was the guy who took care of him. So Don gets me into the Library, where all the inductees go after the ceremonies. Don pulls him aside, and says, ‘Hey, Mick, this is my guy, Bob Costas, and he’d like to get an interview with you.’

“Mickey couldn’t have been nicer, and that night, my short interview with him aired on (WSYR). I still have a picture of the moment, me in my 1974 hair and Pinky Lee sport coat, and Mickey, the new member of the Hall of Fame.

“That was at the start of my career, and I guess you can say, our friendship.”

The day was hardly over, of course. There was the annual Hall of Fame Game at Doubleday Field, this one between the Chicago White Sox and the Atlanta Braves, featuring Hank Aaron, who had recently broken Babe Ruth’s career home run record.

“I remember getting into a limo on the way over,” Eddie Ford recalled. “Well, who’s sitting in it but Warren Spahn, the man who faced my Dad in both the ’57 and ’58 World Series?”

An overflow crowd of 9,975 was in attendance, and at one point, the game had to be stopped because fans broke through the fence to get autographs. They saw Aaron get a hit in his first at-bat, but he was outdone in the Braves’ 12-9 victory by teammate Vic Correll, who hit two home runs and would end his career with 29 dingers – 726 fewer than Aaron. For the record, the other future Hall of Famers there that day were Phil Niekro of the Braves and Ron Santo, then with the White Sox. Playing center field for the Braves was a 25-year-old who would one day climb to No. 7 on the managers’ victory list: Dusty Baker.

Those feelings of Yankees camaraderie and celebration returned in subsequent years with the inductions of franchise legends like Phil Rizzuto (1994), Rich Gossage (2008), Mariano Rivera (2019) and Derek Jeter (2020). But the waters under the bridge have also been tinged with sadness, with the deaths of Mickey and Merlyn and two of their sons, Billy and Mickey Jr., and the passings of Whitey and Joan, their son, Tommy, and their daughter, Sally Ann Clancy.

After Billy Mantle died at the age of 36 in 1994 and right after his stay at the Betty Ford Clinic, Mickey sat with Bob Costas for Later, his talk show on NBC. In a deeply honest 15-minute confessional, Mantle expressed both his regrets and his gratitude. Speaking of the many letters he got at the clinic, he said, “I didn’t realize, until I got those letters, what I really meant to people. In a way…it really helped Mickey Mantle.”

Mickey died of liver cancer on Aug. 13, 1995, 21 years and one day after his induction. In his eloquent eulogy, Costas said this: “We didn’t just root for Mickey. We felt for him. Long before any of us cracked a serious book, we knew something about mythology as we watched Mickey Mantle run out a home run under the lengthening shadows of a Sunday afternoon in Yankee Stadium.”

So much has happened since 1974. But one thing hasn’t changed.

“The Yankees were a family then,” said Dave Mantle, “and we’re a still family now. I love Eddie like a brother. I’m 68 now, but I can close my eyes and see all of us, the Mantles, the Fords, the Rizzutos, the Martins, hanging out on the beach outside our hotel in Fort Lauderdale during Spring Training. I’m smiling now because Eddie and Tommy Ford just dropped a lizard on Phil Rizzuto’s chest, and the Scooter is running into the ocean in fright.

“Those were the days.”

Steve Wulf is a freelance writer living in New York City.

MEMORIES AND DREAMS

This story was originally published in Memories and Dreams, the Hall of Fame’s bi-monthly magazine. Memories and Dreams includes in-depth profiles of Hall of Famers and regular features on unforgettable legends and moments from the National Pastime.

PLAN YOUR VISIT

The memories you’ll make here will last a lifetime. Awed by priceless artifacts. Moved by stories and triumphs that inspired and united a nation. Find your way to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, and you’ll make history of your own.

MUSEUM MEMBERSHIP

Through the Museum's Membership Program, baseball fans from around the country and around the world can be part of the team that is preserving the Game’s history and celebrating the all-time greats.

MEMORIES AND DREAMS

This story was originally published in Memories and Dreams, the Hall of Fame’s bi-monthly magazine. Memories and Dreams includes in-depth profiles of Hall of Famers and regular features on unforgettable legends and moments from the National Pastime.

PLAN YOUR VISIT

The memories you’ll make here will last a lifetime. Awed by priceless artifacts. Moved by stories and triumphs that inspired and united a nation. Find your way to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, and you’ll make history of your own.

MUSEUM MEMBERSHIP

Through the Museum's Membership Program, baseball fans from around the country and around the world can be part of the team that is preserving the Game’s history and celebrating the all-time greats.