- Home

- Our Stories

- Ticket to 'The Show'

Ticket to 'The Show'

MLB’s September roster expansions have given handful of Hall of Famers their shot

Baseball possesses more than a few intricacies that separate it from other sports. In the month of September, however, one rule really stands out.

Starting Sept. 1, MLB teams can expand their rosters and bring each player on their 40-man roster to the big leagues. In other words, rosters swell from 25 players to 40, as more minor league players are made available to be called up during the final month of the season. Suddenly, young prospects who had no influence on the first five months of the MLB season can play a major role in the fall pennant races.

From an outsider’s perspective, the change is truly an anomaly in pro sports. One has trouble imagining an NFL team, for instance, being able to sign additional college players for its final four games, or an NBA team expanding its roster size from 12 to 16 players during the month of May.

So why do MLB teams nearly double their rosters in September? The rule’s original intention was to limit roster sizes, not inflate them. In 1909, the average major league roster numbered 46 players, and some teams including Brooklyn and Boston claimed around 60. The pro clubs, who in the days before free agency had the right to “reserve” a player and therefore restrict his movement, often stockpiled prospects without any intention of using many of them, simply to keep them away from the competition.

That offseason, the National Commission (baseball’s three-man governing body that predated the first commissioner) stipulated that American and National League teams could carry no more than 25 players on their rosters from May 1 to August 20, and set the maximum number on clubs’ off-season reservation lists at 35.

As the Sporting News reported in July 1910, the rule was created to serve two purposes: “First, to check the covering-up practice which has been in vogue since the National Agreement (the peace struck between the two leagues in 1903), in spite of the vigilance of the National Commission; secondly, to curb the extravagance of club-owners…who purchased players in droves, disposed of as many as possible just before the training trip and herded the rest through the South, peddling the discards at reduced rates to minor league clubs.”

That number of 35 would soon evolve into the 40-man rosters we’re now accustomed to seeing every September. While executives and managers have debated in recent years over whether the expanded roster creates unfair advantages for certain teams, the rule undoubtedly has given scores of minor leaguers the chance they desperately sought to prove themselves on the big league stage. In fact, of the 215 former big league players whose plaques reside in the Hall of Fame, a small minority can point to September debuts as launching pads for their celebrated careers.

Here’s a look at some Hall of Famers who started their illustrious careers with an autumn call-up to The Show.

Chicago Cubs manager Phil Cavarreta (center) stands with rookies (from left) Bob Talbot, Gene Baker, Ernie Banks and Bill Moisan in 1953 on the dugout steps at Wrigley Field. The future Hall of Famer Banks hit .314 with two home runs, six RBI and a .956 OPS in 10 September games that year, a performance that won him the starting shortstop job the following season. BL-1735-76 (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

A story entitled "Search for Talent Vigorously Prosecuted by Scouts" (right) on the front page of the Sporting News on July 21, 1910 gives one of the very first explanations of a new rule in baseball that allowed teams to expand their rosters to 35 players after Aug. 20. That rule eventually evolved to the 40-man roster expansion we now see with MLB teams each September. An article in the New York Times on Dec. 16, 1909 (below) also mentioned the rule in passing.

Share this image:

Lou Proves His Worth

Lou Gehrig was a star baseball player at Commerce High School in New York and had earned nationwide acclaim for hitting a grand-slam walk-off home run in a high school championship game at Wrigley Field. Though he failed in a tryout with John McGraw’s Giants in 1921 (Despite hitting six consecutive home runs in batting practice, McGraw reportedly dismissed Gehrig after he booted a ground ball at first base), Gehrig continued to attract attention as a collegiate player at Columbia University. Yankees general manager Ed Barrow signed him for $1,500 in April 1923.

Gehrig played sparingly during the months of June and July before manager Miller Huggins asked him to play the remainder of the year with the Eastern League’s Hartford Senators. Gehrig obliged and proceeded to hit .304 and club 24 homers in 59 games. When the Senators’ season ended in early September, the young prospect was called up to the Yankees and made a much better impression. In just six games, he batted .476 with a home run, four doubles and a triple in 21 at-bats.

Sensing he had a phenom on his hands, Huggins appealed to Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis to make Gehrig a late addition to the Yankees’ World Series roster in October 1923. McGraw, however, loudly voiced his objection and Landis rejected Gehrig’s instatement. Yankee executives sought to give Gehrig more seasoning the following year, and again sent him to Hartford. He simply overwhelmed Eastern League pitchers that season, batting .369 and slugging 37 home runs, 40 doubles and 13 triples. It was then undeniable: Gehrig simply could not be kept out of the Yankees’ lineup any longer.

Lou Gehrig starred at Columbia University before signing with the New York Yankees during his sophomore year in April 1923. BL-1489-68 (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

A Stellar Arm, But A Better Bat

A 20-year old kid named Stan Musial arrived in St. Louis with quite a bit of experience in September 1941. Musial had actually been a promising southpaw pitcher the previous year with Class D Daytona Beach, going 18-5 with a 2.62 ERA. When he wasn’t pitching, Musial played in the outfield, where his career would be forever changed on Aug. 11, 1940.

In center field, Musial dove after a sinking liner and attempted a somersault landing. His spikes caught in the grass, however, driving his left shoulder into the ground. Suddenly, his pitching days were done.

Luckily, Musial proved to be an even better hitter than a pitcher. As a full-time outfielder, he quickly rose through Branch Rickey’s famed minor league system before making his big league debut with the Cardinals on Sept. 17, 1941. The kid from Donora, Pa., went 2-for-4 that day and, appropriately, collected the first of his 725 career doubles – the third-highest total in major league history. In 12 games that fall, Musial hit .426 (20-for-47) and sported an on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS) of 1.023. He also struck out just one time.

The following season, Musial played a full slate and batted .315 – the first of his 16 consecutive .300-or-better seasons – before helping the Cardinals defeat the Yankees in the 1942 World Series.

Stan Musial joined the St. Louis Cardinals just one year after converting from a southpaw pitcher to a full-time outfielder. He batted .426 in 12 games for St. Louis in Sept. 1941, and helped the Cardinals win the World Series the following year. BL-2937-68 (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

Before He Became ‘Mr. Cub’

By the time he made his “debut” with the Chicago Cubs on Sept. 17, 1953, Ernie Banks had already played with the Negro League’s Kansas City Monarchs, barnstormed the country with the “Jackie Robinson All-Stars” and served two years with the U.S. Army. Following a return season with the Monarchs in l953, the Cubs paid Kansas City $20,000 for Banks and pitcher Bill Dickey.

Banks skipped the minor leagues entirely, and if his 10-game September sample was any indication, he was ready for the majors. He hit .314 with two home runs, six RBI and a .956 OPS, convincing incoming Cubs manager Stan Hack to start Banks at shortstop the following year. It was a good decision, as Banks placed second in 1954 Rookie of the Year voting and was well on his way toward becoming a North Side hero.

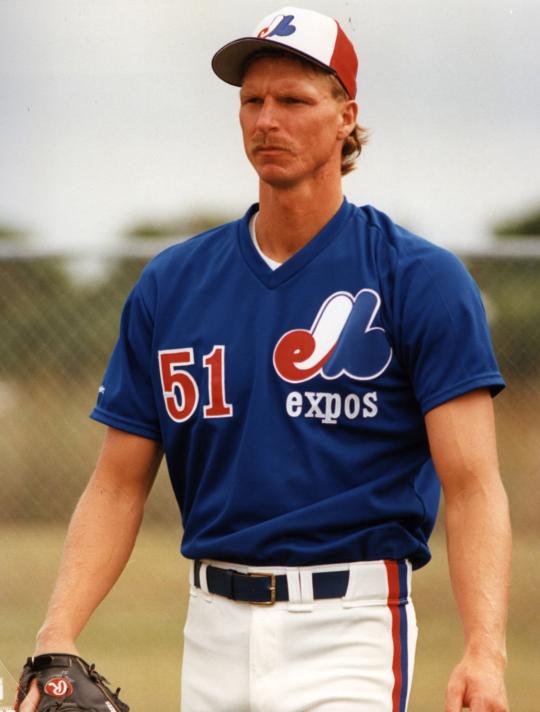

Constructing the Big Unit

By now, most people know the backstory of how a young Randy Johnson struggled with his control. But for his first three starts with the Montreal Expos in 1988, the intimidating 6-foot-10 lefthander seemed to put it all together.

Johnson rattled off a 3-0 record in four starts, sporting a 2.42 ERA with 25 strikeouts and only seven walks in 26 innings. Despite his hot start, however, the Expos were thinking bigger picture at the time. In May 1989, Montreal traded Johnson along with pitchers Gene Harris and Brian Holman to the Seattle Mariners for star pitcher Mark Langston. In Seattle, Johnson struggled at first as he led the AL in walks three straight years from 1990-92. He would finally harness his power in 1993, going 19-8 and finishing second in the league’s Cy Young Award vote.

Inauspicious Starts

While those four Hall of Famers appeared comfortable on the big league stage right away, some fellow legends needed a little more experience after their September debuts.

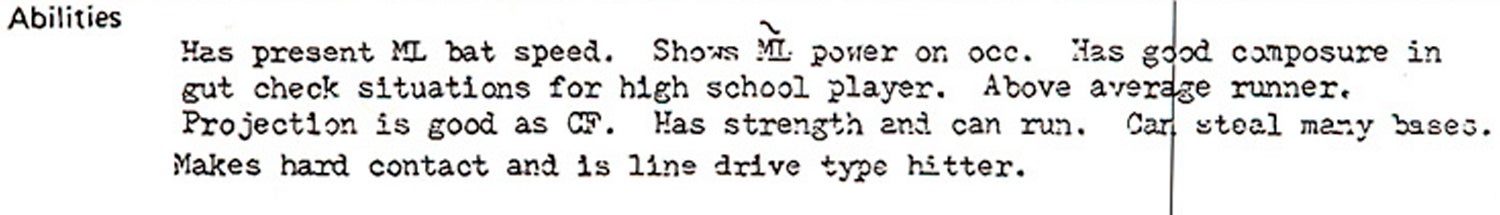

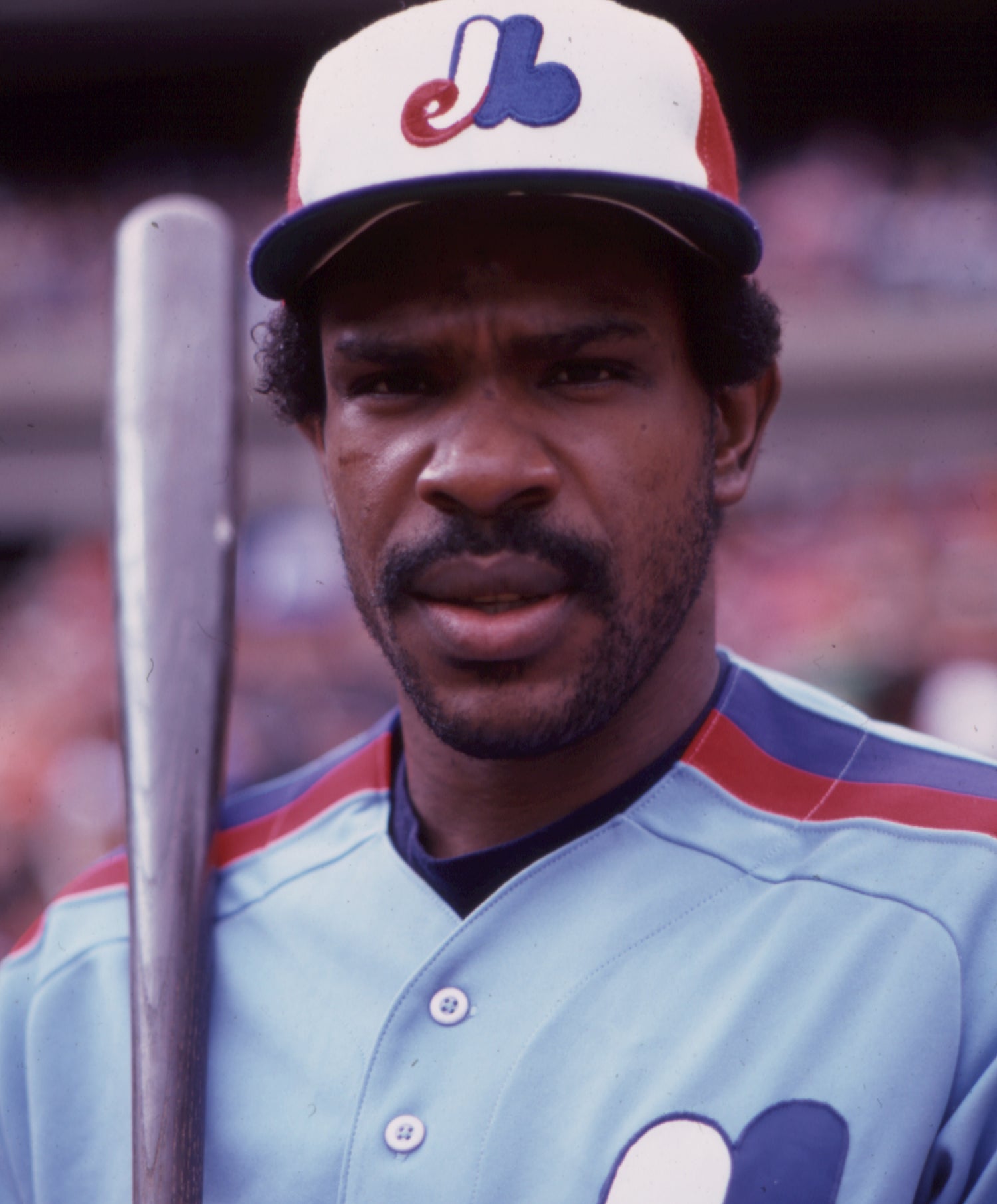

Andre Dawson had already overcome his first of 12 major knee surgeries and had played in just 186 minor league games when the Expos called his name on Sept. 11, 1976. In 24 big league games that season, Dawson batted .235 and showed very little of the power that would later define him at the plate. That quickly changed in 1977, however, when the young “Hawk” batted .282, slugged 19 homers and stole 21 stolen bases en route to winning NL Rookie of the Year honors.

Dawson’s future teammate Ryne Sandberg played 13 games, primarily as a pinch runner and occasional shortstop with the Philadelphia Phillies in late 1981 and batted just .167. Having played second and third base in the minors, Sandberg was blocked at each spot by Phillies full-timers Manny Trillo and Mike Schmidt. That winter, Philadelphia packaged Sandberg and fellow shortstop Larry Bowa to the Chicago Cubs in exchange for Iván de Jesus. The deal would go down as one of the best in the Cubs’ history, after Sandberg moved over to second base in 1983 and subsequently became one of the best to ever man the keystone sack.

Greg Maddux entered his first big league game as a pinch runner for the Cubs in the 17th inning of a game against the Houston Astros on Sept. 3, 1986. In the next frame, Maddux climbed the hill and promptly gave up a home run to Billy Hatcher to take the loss. It was the start of a tough 2-4 stretch with a 5.52 ERA for Maddux in Sept. 1986, although he did make sure to beat his brother, Mike, and the Phillies in his final start of the season. He would struggle again with a 6-14 record in 1987 before breaking out with his first of eight All-Star seasons the following year.

Other Hall of Famers were barely seen in their autumn debuts. Brooks Robinson hit .091 in six games in late 1955. Rollie Fingers gave up four earned runs in 1 1/3 innings – good for a 27.00 ERA – in his lone appearance of 1968. Class of 2015 inductee Pedro Martínez pitched just eight innings for the Dodgers, including two as a reliever, for the Dodgers in 1992.

Passing the Torch

As history shows, it’s tough to predict a player’s chances for Hall of Fame enshrinement based on his first swings or pitches in September. Major League Baseball has certainly enjoyed an infusion of young talent, and late-season prospects like the Dodgers’ Corey Seager and the Rangers’ Joey Gallo have shown flashes of potential this month. But election to the Hall of Fame, of course, entails sustained excellence over many years.

It remains to be seen if this rule – which has been in place for more than 100 years – extends past the next round of negotiations for MLB’s collective bargaining agreement. For now, September remains one of the best times for young ballplayers to land on a big league roster.

“Those guys down there have really worked hard all year,” Giants manager Bruce Bochy said in a recent interview. “And for them, it may be the only time they get called up. If you're able to give them 30 days in the big leagues (and) it turns out it's the only time they get called up, well that makes everything that (they've) done worthwhile.”

Matt Kelly is the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum