- Home

- Our Stories

- Pete Gray overcame a childhood accident to make history

Pete Gray overcame a childhood accident to make history

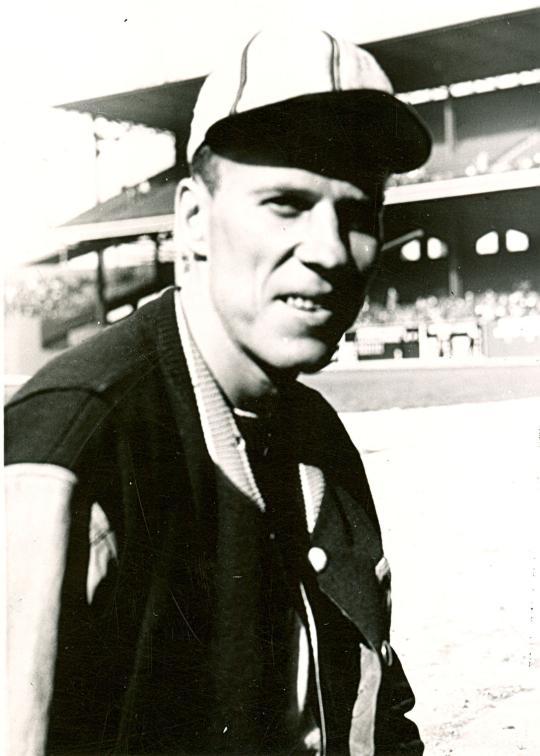

Ordinarily, Pete Gray never would have worn a major-league uniform. He was 30 years old and missing his right arm.

"Son, I've got men with two arms who can't play this game," Connie Mack, manager of the cellar-dwelling Athletics, told him years earlier when Gray requested a tryout.

But by 1945, four years into World War II, more than 500 ballplayers were in the service and filling out a roster was an uncommon challenge at a time when the major leagues still were segregated. So the St. Louis Browns signed Gray to play the outfield.

While Gray played only that one season before returning to the minors, he served as an inspiration to injured veterans and a role model for disabled youngsters.

"Boys, I can't fight and so there is no courage about me," Gray told the Philadelphia sportswriters who named him that year's 'Most Courageous Athlete'. "Courage belongs on the battlefield, not on the baseball diamond. But if I could prove to any boy who has been physically handicapped that he, too, can compete with the best – well, then, I've done my little bit."

Gray, who'd tried to enlist after Pearl Harbor but was turned down, would have preferred to wear a military uniform. "If I could teach myself how to play baseball with one arm," he said, "I sure as hell could handle a rifle."

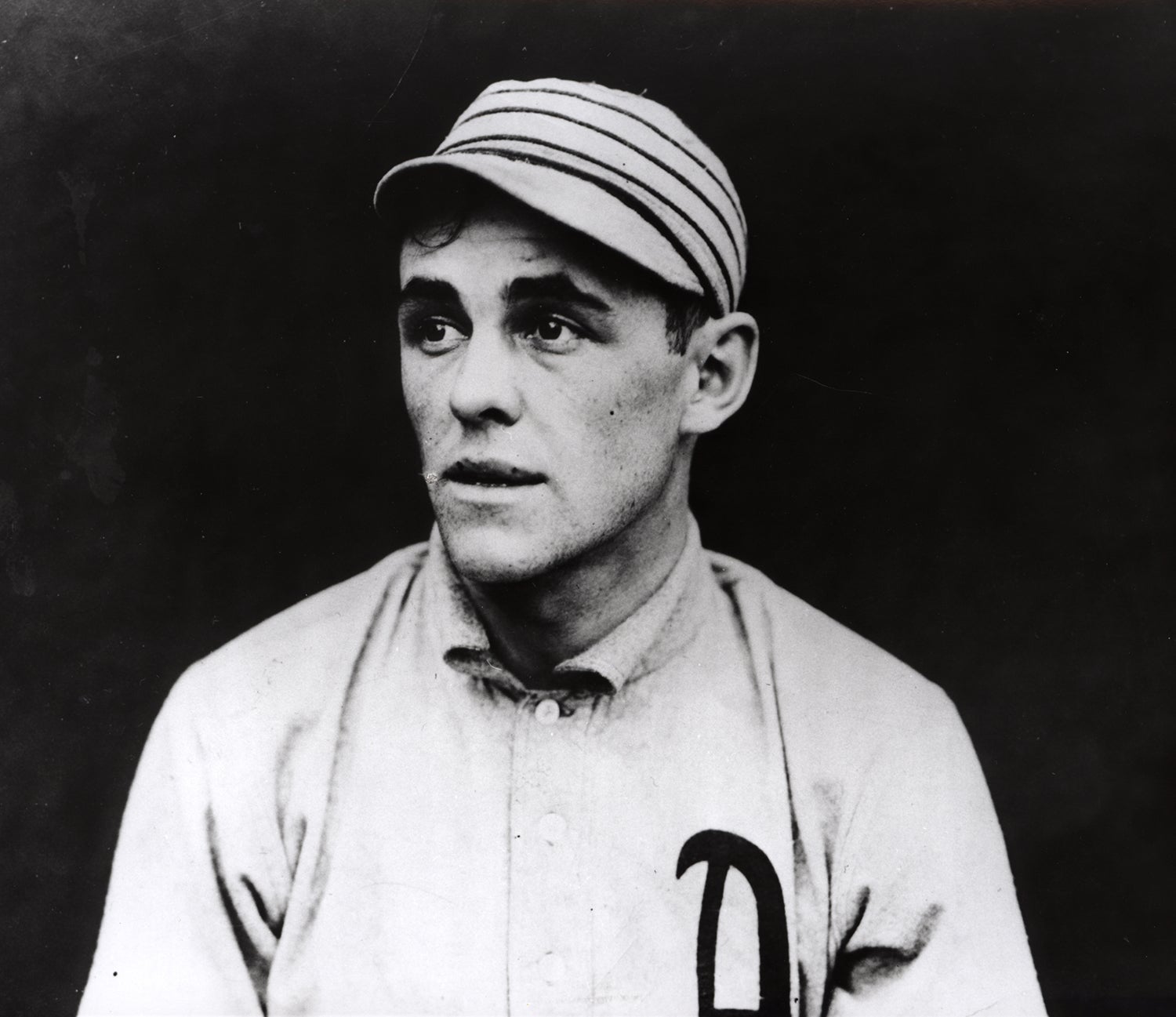

Peter Wyshner, one of five children of a Pennsylvania coal miner who'd emigrated from Lithuania, grew up obsessed with baseball. "There was a team on every street, seven diamonds in the town and kids would always be out playing," said Gray, who grew up in Nanticoke, 20 miles from Scranton, and changed his name as a teenager to avoid ethnic prejudice – as had older brother Joseph when he began boxing.

Gray's life changed painfully and permanently at age six when he fell off the running board of a produce wagon and mangled a forearm in the spokes. Yet he persevered. "Don't let him feel sorry for himself – that's the way my father treated me," said Gray, whose right arm was amputated above the elbow.

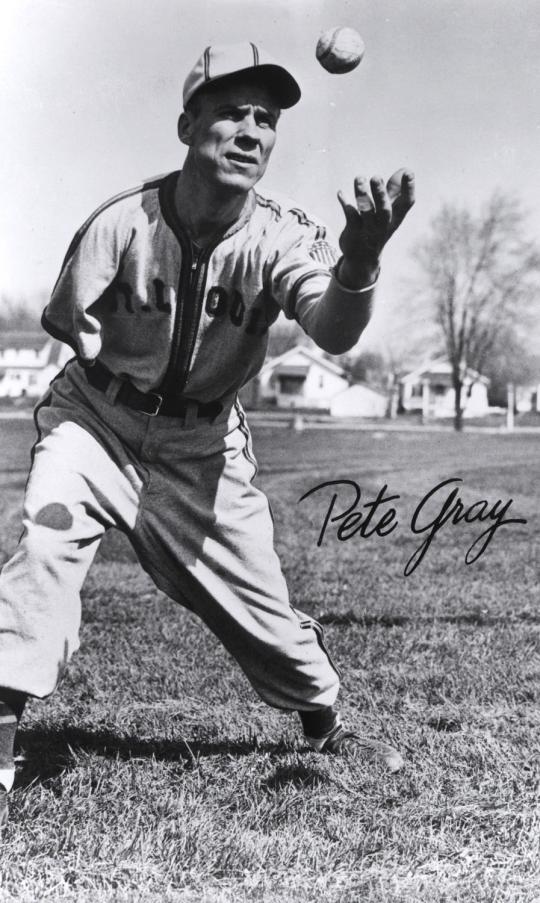

He taught himself to swing left-handed, hitting rocks with a stick along the railroad tracks, and eventually could handle a 38-ounce bat. He devised a way to catch and throw by sticking his glove under the stub of his right arm and squeezing it until the ball rolled across his chest to his left hand.

Yet while he was good enough to play for semi-pro teams on weekends, Gray couldn't get a look from a big league club.

"Get off the field, Wingy, or I'll have the police come get you," Phillies manager Doc Prothro told him at their 1940 camp in Miami.

Gray finally got his shot that year with the semi-pro Brooklyn Bushwicks by handing owner/manager Max Rosner a $10 bill. "Keep it if I don't make good," said Gray, who hit a homer in his first game before 10,000 fans. He ended up batting .350 in his two years in Brooklyn and earned a minor-league spot with Trois-Rivieres in Quebec.

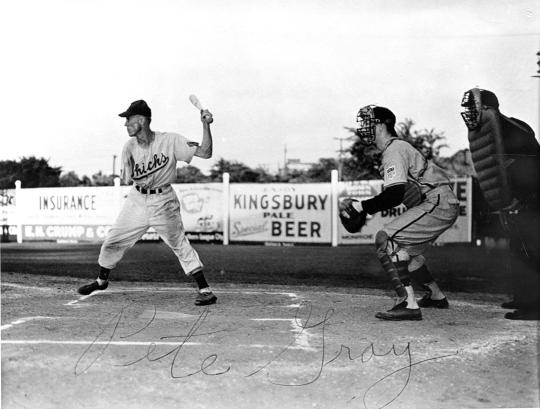

After hitting .381 there, Gray was picked up by Memphis where he played for Prothro. After he was named the Southern Association's Most Valuable Player in 1944 – batting .333 with five home runs and 68 stolen bases – the Browns bought his contract for $20,000, the largest ever for a Southern Leaguer, assigned him No. 14 and paid him $3,000.

Gray received a skeptical reception from his teammates, who'd won the franchise's first pennant the previous year and doubted that he'd help them repeat. "He didn't belong in the major leagues and he knew he was being exploited," said manager Luke Sewell, who told Gray not to expect any favors. "They were trying to get a gate attraction in St. Louis."

Gray, who expected to be judged on his performance, was wary of being regarded as a freak show performer. "He wanted to be known as a ballplayer, not a one-armed ballplayer," said second baseman Don Gutteridge, who later managed the White Sox. "He didn't want to be exploited because he had one arm."

Gray quickly was labeled an ornery loner. "I mostly kept to myself," he said. "That's why I got the reputation of being tough to get along with." But Gray's work ethic won over Sewell. "If handling men were as easy as Pete, it would have been a breeze to manage," he said. "He was perfect."

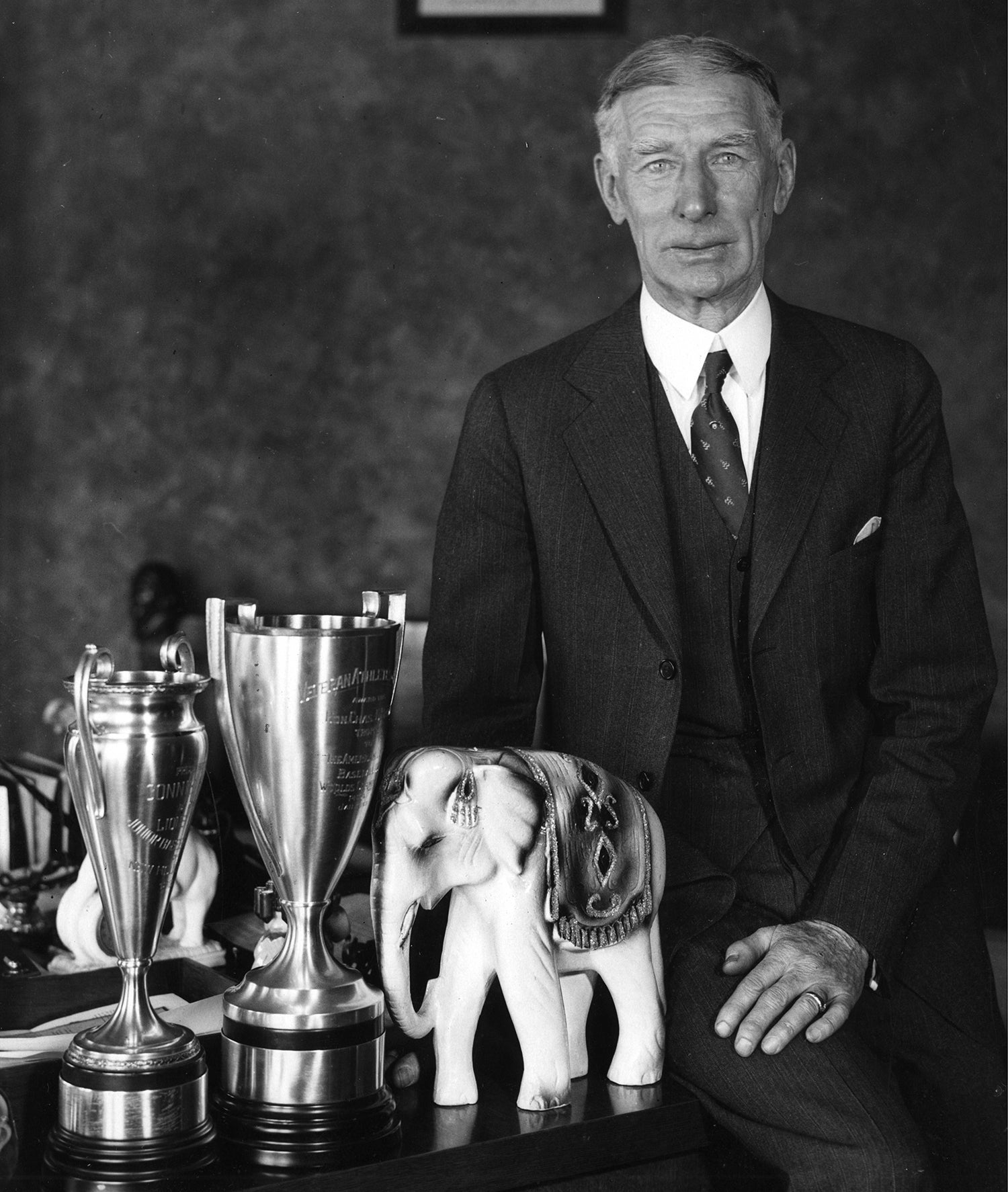

After catching the ball with his glove on his left hand, Pete Gray would pin the glove under the stump of his right arm and let the ball roll down into his left hand, where he would catch it so he could throw. In 29 games as a center fielder in 1945, Gray was charged with just one error. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Gray, who batted .218 in 77 games with St. Louis and struck out only 11 times in 234 at-bats, performed creditably in the early going. He went 4-for-8 with two runs and two RBI in a doubleheader sweep against the Yankees in May and did a capable job in the field, using a minimally-padded glove crafted by a shoemaker that is now preserved at the Hall of Fame.

But it didn't take opponents long to find his limitations. Pitchers knew that he couldn't check swing so they threw him curves and jammed him so he couldn't bunt. By the end of April, Gray was batting only .188 and was benched for eight games in early May.

Yet Gray had an impact well beyond the ballpark. Everyone in America knew about the Browns' one-armed wonder, who was featured in a Universal movie newsreel. He visited Army hospitals and rehab centers to meet with amputees.

How well would Gray have fared had he had two arms? "Who knows?" he mused. "Maybe I wouldn't have done as well. I probably wouldn't have been as determined."

Determination, though, wasn't enough to keep him in the majors. After being benched for most of September, Gray reckoned that he'd be returning to the bushes.

"I figured I had a bad year and I knew I was going back," Gray said. "I knew I was going somewhere. I didn't care as long as I was playing baseball and it was every day. The only thing I wanted to do when I was a kid was play in Yankee Stadium and that came true."

Meanwhile, the war ended and the regulars came back – only three of the Browns field starters returned for the 1946 season. With the diamond level again, the Browns' reverted to their usual place in the standings. They finished seventh, 38 games behind the Red Sox, were back in the American League cellar the following year and didn't have another winning campaign until they departed for Baltimore in 1954.

Gray played a year for the Toledo Mud Hens then proceeded to Elmira before ending his career in Dallas in 1949.

He returned to Nanticoke and his childhood home, barnstormed for a few years and discouraged interviews (“I've nothing to say”). Yet Gray's story endured, highlighted in 1986 by a TV movie ('A Winner Never Quits') starring Keith Carradine.

That was his proudest achievement, Gray told a nursing home visitor: "I never gave up."

John Powers is a freelance writer from Brewster, Mass.